Postal history artifacts - old covers that carried letters, business correspondence and other items through the mail - provide us with opportunities to explore things that once were and meet people that are no longer with us. Today, I’m going to focus on the address panel of three (almost) covers and see where they lead me.

I expect there might be a few surprises for me as I work on this week’s edition - and perhaps for you as well. So, grab a snack and a favorite beverage. Put on the comfy slippers and sink into that favorite reading chair.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

A Gettysburg address

Our first cover will get the attention of people who have studied the US Civil War. The postmark on the stamp is for Gettysburg, Pennsylvania - as is the addressee.

This is what is known as a “drop letter” which was essentially a local letter rate. The sender went to the Gettysburg post office and dropped the letter off for Sallie M. McClean. Sallie would pick up this letter when she (or a member of her family) came to the post office to pick up the mail.

The normal cost to mail a letter from one place in the US to another was 3 cents per 1/2 ounce of weight. But drop letters qualified for a special postage rate.

Most towns and cities in the United States in the 1860s did not have postal carrier services. Individuals had to send someone to the post office to drop off and pick up their mail. Gettysburg was no exception and I am certain Sallie McClean and her family had trips to the post office as part of a normal routine.

This letter was mailed after August 20, 1861, which is when the 1 cent postage stamp design was first used. This design was no longer printed in 1869, so it is safe to say this letter was mailed in the 1860s. The 1 cent special drop letter rate was in effect in 1861 until it was modified to 2 cents on July 1, 1863. It was again dropped to 1 cent for post offices that did not offer carrier services on May 1, 1865. This letter has no markings or contents that can provide us with a year date, but this knowledge of the drop letter rates provide us with the reasonable options.

The address on this letter is:

Sallie M McClean, Gettysburg, Penna

Anyone who is familiar with US history during the 1860s is going to have some knowledge of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863). It was one of the most important and was, by far, the bloodiest. An estimated 51,000 casualties can be attributed to this battle.

Sallie McClean’s family lived at 11 Baltimore Street in the town of Gettysburg at the time the fighting began. Her house still stands in the middle of the town and it was hit with an artillery fire. Apparently, a person can go there and see a shell stuck into the side of the building even today.

I mentioned there might be some surprises for me. The first was that I could find the McClean’s so easily. Hunting for an addressee often requires a great deal of hunting. The second had more to do with my own personal perceptions of the battle of Gettysburg.

I am among those who envisioned the fighting in the country outside of town, as depicted in the image above. And I have seen the images of the dead, including this photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan, where the fighting was clearly outside of the city limits. I recalled that Pickett’s Charge took place south of town and I simply inferred that this is where the battle took place in its entirety.

I was surprised to learn that some of the action took place inside the town itself. The battle was initiated north of town and, at the end of day 1, the Union troops retreated through the town towards high ground to the south. If you are interested, this video created by the American Battlefield Trust will give you a summary of the fighting including mention of the dedication of the graveyard where Abraham Lincoln gave his Gettysburg Address (about 16 minutes long).

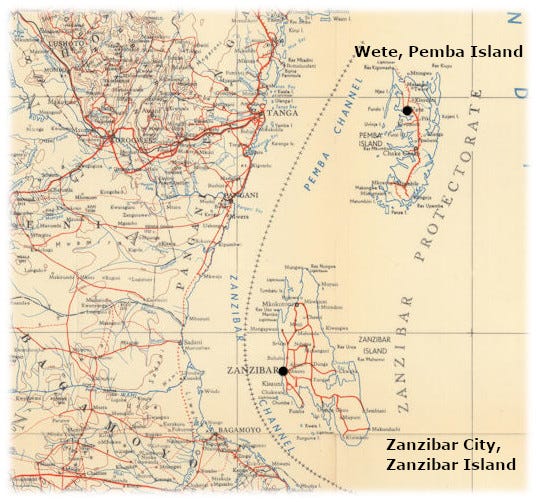

The McClean family also owned a farm that was being managed by a tenant (Mr. J. Martin) at the time. The buildings on that farm were in the thick of the fighting during Day 1.

Gettysburg was of interest because eleven roads, some of them private, converged upon the town. This made Gettysburg a likely place for a battle since control of an important road junction could make a significant tactical difference in the hills of Pennsylvania.

On June 26, Confederate Major General Jubal Early took his forces through Gettysburg seeking supplies, especially shoes. That would have been the first interactions the people of Gettysburg would have had with respect to the impending battle.

When the battle was complete (and during the battle) homes, barns and other structures were converted to makeshift hospitals and the general populace of the town participated in caretaking of the sick and wounded. Apparently Sallie spent some time gathering battlefield items and they are now in the collections of Gettysburg College’s Musselman Library.

Sallie would have been a young woman (born in 1842) at the time of the battle and lived with either her father or uncle, Moses. Moses was a lawyer, but had also served in the US House of Representatives and in the Pennsylvania legislature.

As an individual who has never had to observe two armies fighting in my home town or on my farm, I can only imagine how this must have impacted Sallie. But my imagination is good, and I hope yours is too. Because this is a time when having a good imagination can encourage us all to do what it takes to avoid actually living these sorts of events.

Stone Town

The next address just might be as far away from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania as we can get! It is addressed:

“To Food Return, Imp. & Exch. Controller, Custom House, PO Box 161, Zanzibar”

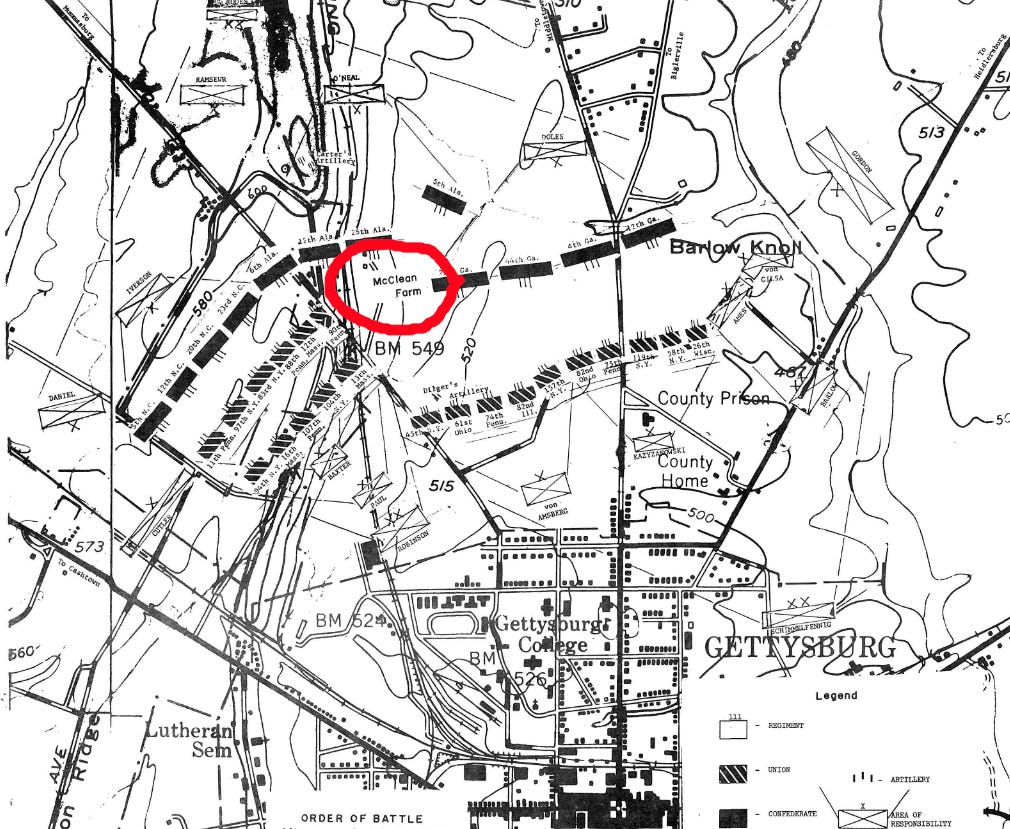

This envelope was mailed from Wete on Pemba Island, which was also part of the Sultanate of Zanzibar (merged with Tanganyika in 1964 to form Tanzania). I do not have resources to confirm internal rates for Zanzibar nor have I found an online resource, but 10 cents seems like it would be reasonable postage for a simple letter.

A return address on the back confirms the Wete, Pemba, origin and the postmark tells us that the letter was mailed in 1955. Unfortunately, the rest of the date is not readable.

Customs Houses were staffed by government officials that oversaw the import and export of goods and they would typically be found in port cities. These officials would collect customs duties or tariffs on incoming products and might also be involved in exchange disputes. Is it possible that the words “Food Return” gives us an idea that this envelope held a complaint regarding a shipment of food products? There are no contents, which is often the case with pieces of postal history, much to my chagrin.

So we can only use our imagination, once again, as to what this envelope carried.

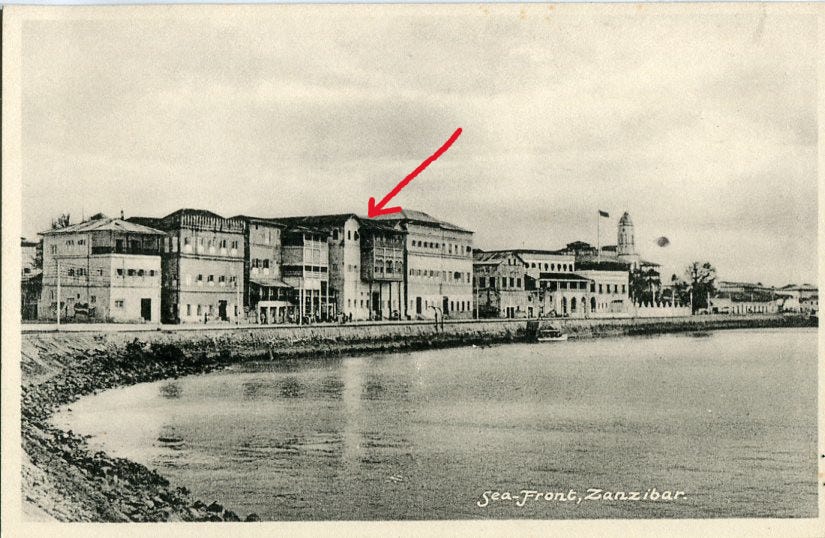

At the time this letter was mailed, the Custom House in Zanzibar City was a large building in an area known as Stone Town or Mji Mkongwe (Swahili for “old town”). On image below from the 1930s shows the Custom House with a three-story, cast iron balcony on the front. The large building to the right was Le Grand Hotel.

The Custom House was initially constructed at some point during the reign of Sultan Majid Bin Said (1856 - 1870). It was built by the Busaidi family (a branch of the ruling family) and they maintained control of it until 1928. It was at that time that the Customs offices were moved from a nearby shed to this house.

Stone Town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As such, there have been efforts to rehabilitate prominent buildings like the Custom House. Customs House was abandoned in 1987, but rehabilitation work started in 1993. A large, three-story, cast iron balcony had been added in 1896, but removed and stored inside the building (in pieces) in 1989. It was restored in 1998.

According to the Archnet site:

The construction systems reflect traditional building practices in East Africa: coral masonry laid in lime mortar, wall surfaces covered with coral lime-based plaster, coral rubble ceilings supported by exposed timber joists, and a flat roof with a crenellated parapet. The width of the rooms is determined by the span of the structural joists, an average of four metres.

This was my second big surprise for this Postal History Sunday. Imagine how short this entry would have been if the Customs Office had remained in the shed that is, most likely, long gone? How likely would it have been that I would have found much of anything to write about if the building that was housing the Customs officials were not a UNESCO World Heritage site?

Not very likely.

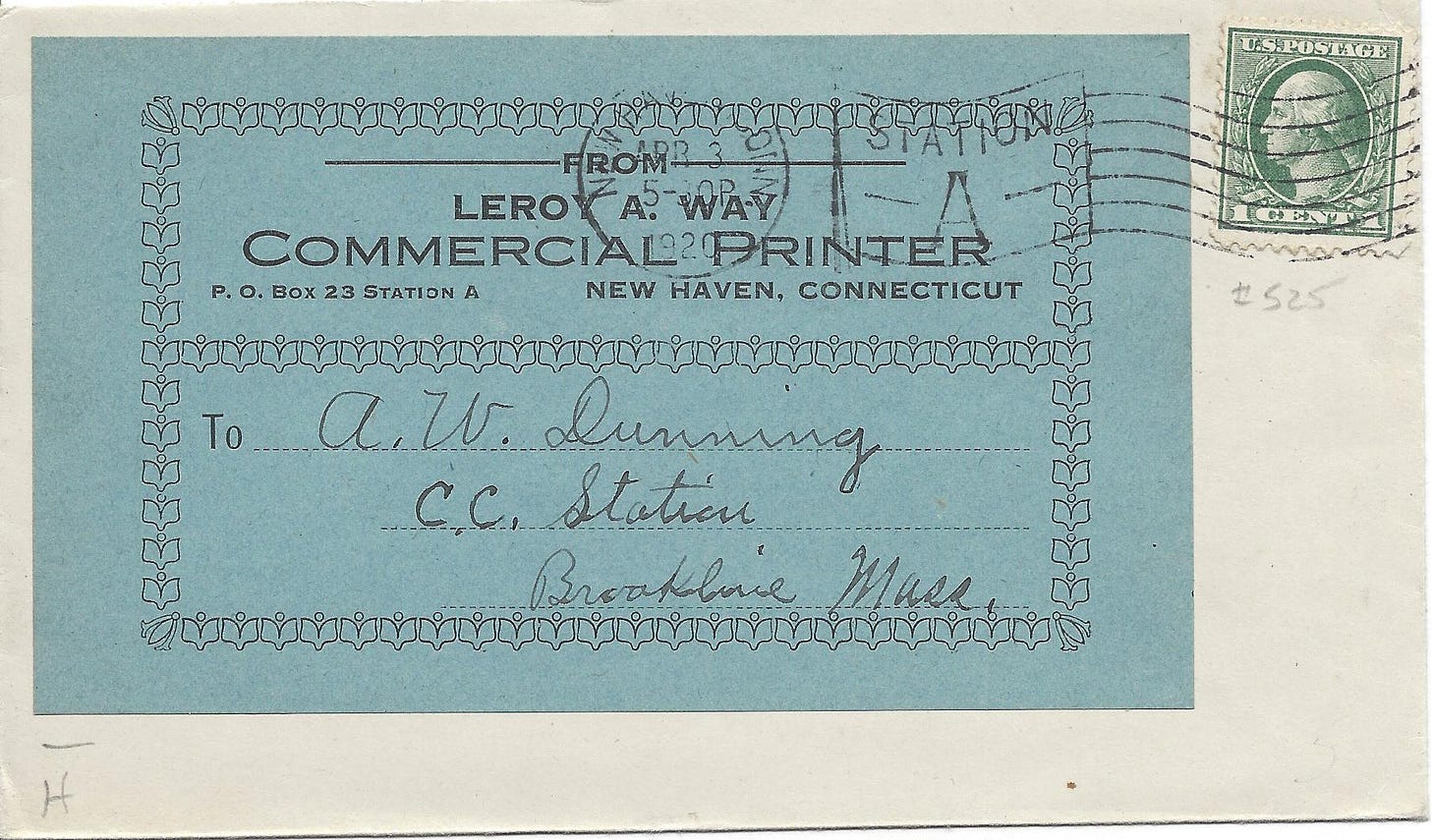

Coolidge Corner

I am only going to show you cover number three because time is making a fool out of me. This happens most often when I am discovering interesting new things.

This last cover will be part of one of the next few week’s edition of Postal History Sunday. We’ll figure out what C.C. Station might be and maybe even learn a thing or two about A.W. Dunning.

Thank you for joining me. I hope you enjoyed this edition of Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack.