A Nickel More

Postal History Sunday #213

I am happy to be one of the people in this world who is afflicted with a love for the game of baseball. I will admit that I probably enjoyed playing more than I do watching, but I still listen to games on a fairly regular basis. Recently, I had a game on in the background while I was doing some work on the farm and heard the announcers say, “Well, there’s something you don’t see every day.”

Unfortunately for me, this was a radio broadcast and I had to rely on their words to paint the picture for me. Still, they got my attention and I even took the time later on to seek out video footage. You see, I know that these radio announcers have seen many more baseball games than I ever will. So, when they told me something special is going on, I was quite willing to pay attention.

Today’s Postal History Sunday is going to be my equivalent of “there’s something you don’t see every day.”

I’ve probably spent more time than 99% of the world’s population looking at covers that feature the 24-cent denomination of the US 1861 issue of postage stamps. While I will not be so bold as to say I have the most knowledge or experience (I am pretty sure I don’t), I don’t think it is unfair to draw a rough equivalency between myself and those baseball radio announcers. If I bother to say “hmm, I haven’t seen that much,” it probably means there aren’t many of that sort of thing to see!

How this letter got from here to there

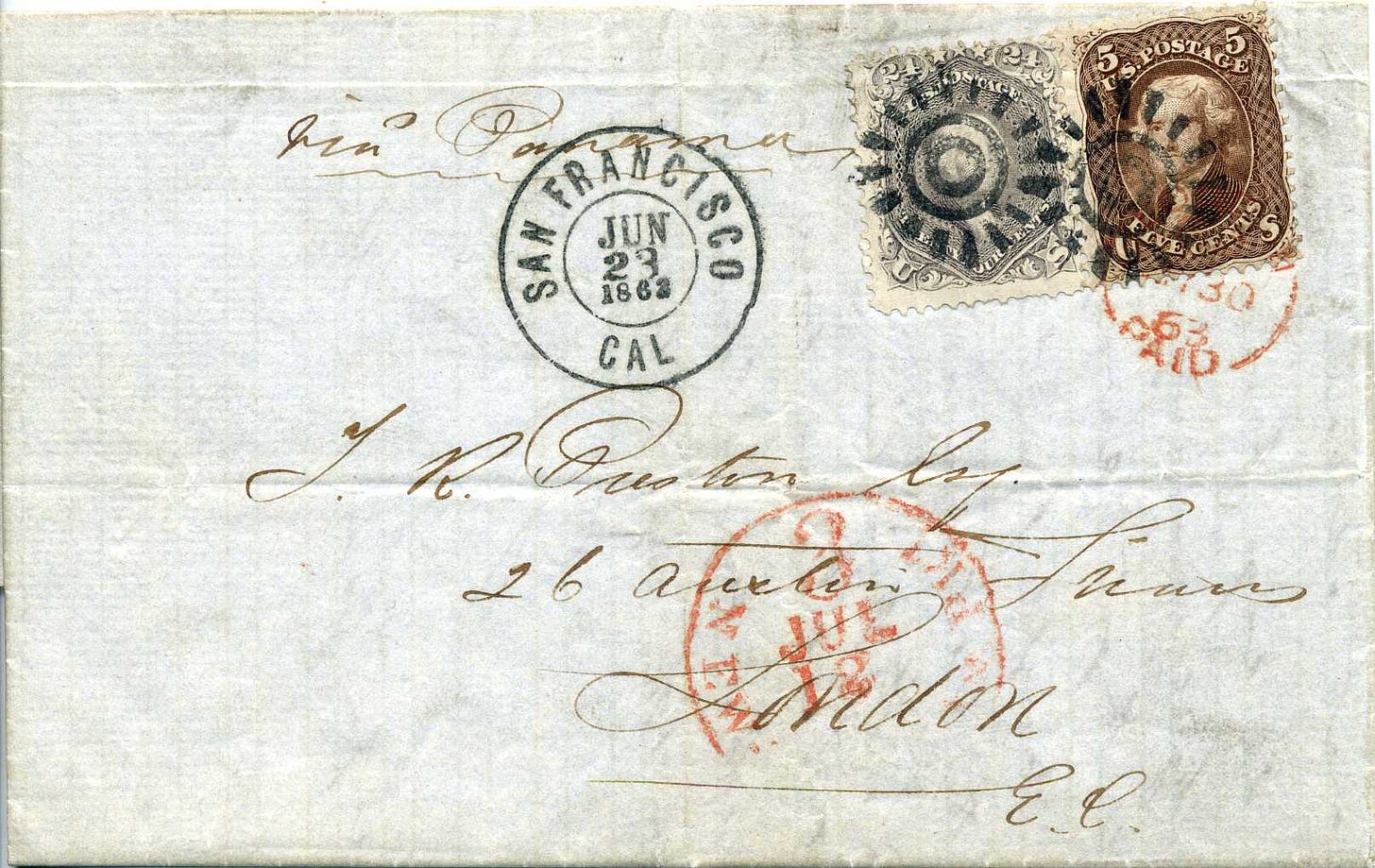

Here it is - something you don’t see every day. But, before I give you an explanation as to why that is, I’d like to get some of the basics of the cover fleshed out.

The folded letter shown above was mailed in San Francisco in June of 1863 and departed on the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s Constitution on June 23 for Panama. We need to remember that the San Francisco post office used the date of the ship departure in their postmarks for letters intended to go through Panama. So, it is possible that the sender dropped this off at the post office before that date. However, the contents of this letter also show a dateline of June 23, which makes it likely it was brought to the San Francisco on that day prior to the closing of the mails due to leave for Panama.

The letter crossed at the isthmus of Panama and took ship again to New York City. The New York Times clipping shown above seems to indicate that the Ocean Queen was carrying the US Mails, departing Aspinwall on the 8th and arriving in New York on the 16th. The New York Foreign Mail Office then did its duty as an exchange office with the United Kingdom. It placed a red exchange marking dated July 18, which corresponded with the trans-Atlantic sailing set to depart on that date.

The Inman Line was one of three steamship companies that carried mail across the Atlantic Ocean on Saturdays (in 1863) from New York. It just happens that neither the HAPAG nor the North German Lloyd had ships departing this particular Saturday so we can deduce that this letter traveled on the City of Washington to Queenstown, Ireland (Cork) on July 28.

At this point, the letter likely took the train to Kingstown and crossed by steamer from Ireland to Holyhead. It would then board another train to London. However, given the two day transit, it is possible this letter stayed on the City of Washington until it got to Liverpool on the 29th. Regardless of the route, the letter was taken out of the mailbag in the London exchange office and marked with the red July 30 marking that can be seen up by the postage stamps. At that point it was delivered to the intended recipient, T. R. Preston, Esquire.

What was in this letter?

The contents of this folded letter are very brief and are clearly an attempt by a person on a ship to keep the addressee apprised as to the progress of their travels.

“I have to advise you that I arrived here yesterday in 25 days from Callao [Peru]. We have about 1 1/2 days coal over by economizing as much as possible. I expect to be able to get away to Victoria [Australia] on the 26th.

One of our bunkers caught fire spontaneously during the voyage but we managed to extinguish it and clear it out. I hope without damage.”

The remainder of the letter appears to discuss a cargo picked up in Valparaiso, Chile that they were successful in selling. In addition to the letter content, there are two additional pieces of information that help us confirm how and when the letter made its journey.

The bottom of the letter includes a postscript telling the recipient that the “mail for Europe goes out this morning.” Since the letter is dated the 26th, we can conclude that the person writing this letter did make sure to get to the post office before the mail leaving for Panama (and Europe) closed.

I think it is worth noting how important mail closing times (and dates) were to people sending mail correspondence in the 1860s. It’s a good reminder that letter writing was the primary, and often only, way to communicate from a distance. There was no calling someone up on a phone and I suspect email / internet services were spotty at best (hint - I’m trying to be funny here - emphasis on trying).

The recipient of this letter recorded, for their own purposes, that they received this letter on July 30 - the same day the London exchange office placed their mark on the letter. And, if you are interested, they even did the math to determine that it took 37 days for this letter to get from San Francisco to London.

It doesn’t take much imagination to guess that this letter writer sent a letter detailing their progress while they were in Callao, Peru, twenty-five days prior to sending this missive from San Francisco. To give you perspective, the letter telling T.R. Preston that the ship was in Callao would have been ten to twelve days away from being delivered at the point this letter was being written. And, if everything went well for the ship, it had probably left San Francisco for Victoria four days before this letter got to London.

The receiving docket also indicates that T.R. Preston answered this letter on November 26. Clearly, they weren’t in a rush to send a note back and I think you can guess why. The letter writer was a moving target as they sailed with their ship. Preston probably was waiting for a point in the itinerary where it would be likely the letter and the recipient would meet.

Bunker fire!

It is quite surprising to me how concise this individual was in writing their letter. Many business letters of the time included some standard introductory sentences that rarely provided much in the way of information - but this individual dispensed with the unneeded pleasantries. Not only did this person provide a travel update and a cargo update - they also shared the news of what could have been a disaster for the ship in just a few sentences.

The video shown below is hosted by the Independence Seaport Museum. While the video features a steamship that was built thirty years after this letter was sent, it can give you a good idea of what a bunker fire might mean for a steamship at that time.

For those of you who don’t want to invest four minutes on a video, I can summarize in a few words. The bunkers were the locations where coal was stored. That coal would be moved to the boilers so it could be burnt to create steam, which would then propel the ship. To put it bluntly, a fire in a bunker was NOT a good thing. That coal was not supposed to be burning until it got into the boilers, where the energy could be captured for use by the ship.

Coal bunker fires were not an uncommon event and systems were developed over time to deal with them when they occurred. But, steamships were still relatively new in 1863. A coal fire then would probably have more peril attached than one in 1905 and it would have been less catastrophic than one in the early 1850s. The writer of this letter clearly thought it was a noteworthy event, mentioning it even before getting down to reporting business transactions.

Something you don’t see every day

I can hear the grumbling in the audience and I think I had better address it before it gets out of hand. I built up the idea that we were seeing something that you don’t see every day and then I went off on steamships, coal bunkers and the contents of a letter. And before you ask - no. None of those things were the “thing you don’t see every day” that I was referring to.

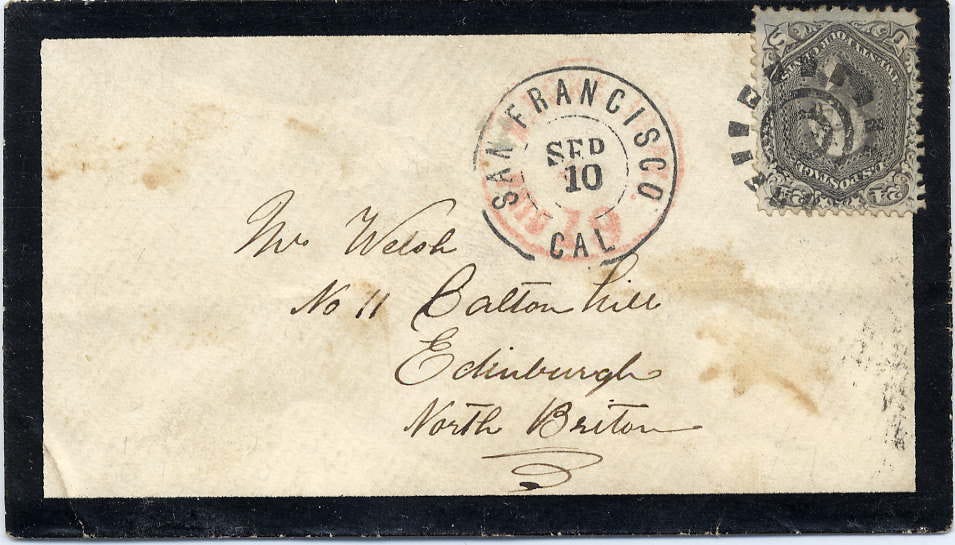

To set up the grand reveal, I’d like you to take a look at this envelope that was sent from San Francisco to Edinburgh in 1867. The postage rate for a simple letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce from the US to the UK was 24 cents. This is a fairly typical cover that features a 24-cent 1861 series stamp that paid the postage for mail from the US to the UK.

Now, take a look at our first cover again.

The biggest visible difference is the addition of a second postage stamp on this cover. In addition to a 24-cent denomination, there is a brown 5-cent stamp that features the image of Thomas Jefferson. The postage rate for a simple letter was still 24 cents - but there was a special exception for mail between the United Kingdom and the West Coast. The rate for mail was 29 cents for a simple letter, which was equal to 1 shilling and 2 1/2 pence.

The 29 cent rate was terminated on July 1, 1863 when 24-cents went in effect for all US locations. That makes this letter even more interesting because it was mailed prior to that date, but it did not leave the United States until after the July 1st changes went into effect.

The 24-cent 1861 issue began seeing use in August of 1861, which means we have just under two years where the 29-cent rate and the stamp coexisted. The bottom line is this - I’ve only seen this postage rate illustrated on covers with the 24-cent 1861 stamp a few times. That makes it something you don’t see every day - even if you do look at 24-cent covers most days of the year.

Part of the reason for the relative scarcity of this sort of cover was that some postal customers used three 10-cent stamps or a single 30-cent stamp and simply overpaid the rate by one cent as a convenience. The other part of the equation is the relatively low volume of mail from the West Coast to the UK as compared to the much greater volume of mail from the rest of the US to the UK. Simply put, there were many more examples of the 24-cent rate than the 29-cent rate to begin with. Maybe one in two hundred letters between the two postal agencies dealt with the West Coast (and that’s a conservatively high estimate).

The envelope shown above illustrates the postage rate going the “other way” from the United Kingdom to San Francisco. The three British stamps total 1 shilling and 3 pence in postage, which is a 1/2 penny overpay. The British post had no 1/2 penny postage stamp, so this rate was a bit of an inconvenience in that respect. Either a person overpaid a little or they paid the difference in cash.

In fact, it wasn’t all that uncommon for people to simply pay the 1 shilling in postage and underpay the rate. The letter shown above has two 6 penny stamps (equals 1 shilling) which was recognized as being insufficiently stamped. The recipient in San Francisco had to pay the 6 cent “ship fee” to cover the extra costs.

The topic of special postage rates to the West Coast, including this rate to the United Kingdom that required a nickel more, can be a fairly complex one. Even the background and particulars of the 29-cent rate could provide an opportunity for some in-depth exploration.

And this is where I show you one more cover that was mailed from Oakland, California. There is a lot going on here and it is worthy of its own Postal History Sunday. In fact, it can help us tell even more of the 29-cent rate story. Consider this a teaser - some Sunday in the future is coming when we get to dig into this cover.

I, at least, am looking forward to it.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Thanks, Rob. I look forward to more "29 cent stamp" stories. And a bunker fire? Sounds scary to me.

Thanks Rob! This PHS really drives home the importance of written communication. Only 162 years ago, communication (like this note to you) which can move at the speed of light - took weeks! Also, how critically important postage rates were when mail was so vitally important for the day to day functioning of business and the world. I'm a fairly old guy, but it is still easy to forget how much we NOW take for granted, and how unimaginable what we have now would have been in 1862 - only about 2.4 of my own 'lifetimes' ago.