Another Merry Chase - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday, a weekly writing that is published on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog for all who might be interested. For those who might be new - or if you've missed this sort of introduction before - Postal History Sunday started as a "pandemic project" where I, Rob Faux, a vegetable/poultry farmer and postal history collector, decided to share this hobby I enjoy with anyone who might want to read about it. This will be the 68th "official" entry in the series.

Everyone is welcome and I try to write so that persons with no personal history experience can still appreciate what I am sharing. At the same time, I do my best to provide some "meaty details" that other postal historians might appreciate. It is my hope that everyone who reads these posts will find something to enjoy and, perhaps, learn something new.

Now, put on the fuzzy slippers and get a favorite beverage - keeping it away from the keyboard and the old paper items. Pack up those troubles and worries. We don't need them right now. And let's see where we can go with a new "merry chase." The first entry to feature a merry chase was published in September and received positive feedback - I guess I'll just have to do my best to live up to it.

Cutting to the Chase

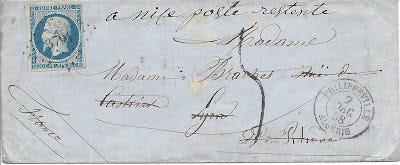

Today's merry chase features this envelope that was mailed from Philippeville, Algeria to Lyon, France on December 7, 1858. Already we can see that this letter must have been forwarded at least once because the address "Rue de Castries, Lyon, Rhone, France" has been crossed out.

A new address has been placed at the top which reads "a nice poste restante." It seems likely that Madame Brachet had gone to an area that is now known as the French Riviera or the Côte d’Azur. In the 1850s, it was already well known as a health resort, especially by the British elite. So, apparently, we have a person who likely had money, or was connected to someone who could host them.

But, what does "a nice poste restante" mean, exactly?

The first part is probably not so hard for a person who knows something of southeastern France. Nice is one of the larger settlements on the Mediterranean Coast, so the first part means "in Nice." But, no address is given for Madame Brachet. Instead, the words "poste restante" tell the postal services in Nice to hold the letter at the post office for the recipient to pick up the letter.

And, since the postage had only been provided to mail the letter from Philippeville to Lyon, she would have to pay additional postage, which was indicated by the black squiggle in the middle of the envelope (we'll get to that later!).

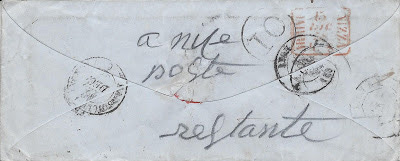

And, here is the back of this small envelope. Once again, we see "a nice poste restante," but written in pencil and there are a few postal markings here. So, let's run down what the postal markings say (at least the ones I can read).

Philippeville, Algerie Dec 7, 1858

Marseille A Lyon Dec 12

Lyon Dec 13

Lyon A Marseille

Nizza Arrivo Dec 15

IO in a circle

The travels of this letter can be seen below. Remember, you can click on an image to see a larger version.

This piece of mail traveled by steamship from Philippeville to Marseille and them by train form Marseille to Lyon. The train trip is confirmed by the Marseille A Lyon marking, which would have been applied in the mail car on the northbound train.

There are two Lyon markings on the back and I can only read the date on one of them. One was likely applied when the letter was received and delivery was attempted. The "IO" was probably applied in Lyon for the carrier route or distribution, but I have not confirmed that as a certain fact. It was determined then that Madame Brachet was away and instruction with a new address led to the letter being forwarded without postage.

Back on the train (Lyon A Marseille), the letter would return to Marseille. I am taking a guess that it may have left Marseille on the 14th to take the train to Toulon - which was as far as the train went at the time. It would have to be carried by coach the rest of the way to Nice.

And there it sat - at the Nice post office - waiting for Madame Brachet.

So, who was Madame Brachet?

Unfortunately, the contents of the letter are no longer with the envelope, so we don't have much more to go on other than to search to see if we can find family in the Lyon area during this period in time. Since we are fairly certain that this is a person with connections, we can make some additional educated guesses. It turns out that our addressee may well have been related (a newly widowed spouse?) to Jean-Louis Brachet (1789 - Apr 10, 1858) who is profiled in a book edited by Stephen Ashwal (photo from that book). [1]

Jean-Louis applied to Hôtel Dieu, which had served as the main hospital facility in the Lyon area for centuries, to study medicine at the age of 17. He became a surgeon intern after seven years and adjunct surgeon after only five more. He was appointed as Napoleon's personal surgeon during the latter's exile in Elba until Brachet contracted typhus and returned home.

He was a prolific author of medical materials on a wide range of topics. His first paper was published in 1813, but he is best known today for Traite de l' Hysterie (Traits of Hysteria, 1847) and his work regarding convulsive disorders in children.

This is certainly an interesting diversion, but how certain can we be that the recipient of this letter was, indeed, related to Jean-Louis Brachet? The answer is, we cannot. But, we have clues that could, if I wanted to pursue it further, help to prove or disprove the theory. For now, we'll just leave it as an interesting, and plausible, side story that Brachet's widow was able to go to Nice and get her mind off of the recent loss of her husband.

What qualifies as a Merry Chase?

"Merry chase" is an "official" Postal History Sunday term. And, as such, I can define it any way I want to. I suppose I could just say it is any piece of postal history that makes Rob say, "what a merry chase," but that would probably be viewed as an unsatisfactory definition by everyone except me.

One way an item qualifies is if it was forwarded to a new destination two or more times. For example, something like the letter below would work.

Miss S Louise Jewell was clearly traveling Europe in 1914 and this letter chased her around Europe and clearly did not catch up until she returned to college in Claremont, California. Letters to persons traveling abroad often provide us with excellent opportunities for a merry chase.

The second characteristic that gets me to qualify something as a merry chase is if an item was forwarded to a new destination once, but the travels provide me with enough interest that I happily dive into the details. That is what today's featured item provides.

One-third of the French Riviera wasn't

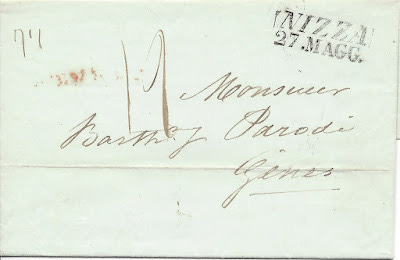

In today's world, Nice is a city in France and the French Riviera reaches all the way to Menton, at the border with Italy. However, in 1858, Nice was on the border of France and the Italian state of Sardinia. In fact, Nice was on the Sardinian side of the border! Madame Brachet had actually left the country.

It would not be long before this region would be ceded to France by Sardinia in exchange for France's help during the Italian War of Independence in 1859. This area was actually the eastern portion of the County of Nice. The western section of the county had already been annexed by France in 1792.

After the regional referendum that confirmed the cession of territory to France, many disappointed Italians relocated themselves in protest to the Italian settlements to the East. This is referred to as the Niçard exodus.

Shown above is an 1847 folded letter that was mailed from Nice (Nizza) when it was within Sardinian borders and well before it was given over to France. This business letter was sent to another Sardinian city, Genoa (Genes). The smaller markings at the top right read 7'1, which indicated that the weight of the item was 7.1 grams. This was too much for a single weight letter at that time, so it was rated as a double rate letter.

The other, larger scrawl is a "12," which would be consistent with two times the 6 soldi rate.

And here is another folded letter (1864) that was sent from Genova (Genoa) in the newly unified Kingdom of Italy. This item was sent to Nice (Nizza Marittima), but it required foreign postage because this was now a foreign letter (40 centesimi per 10 grams : Jan 1, 1861 - Jul 31, 1869).

This brings us back to our featured, merry chase, cover!

The large, dark "squiggle" at center right on this envelope is a "5," which would have been the proper rate for a foreign letter received in Sardinia from a French origin. Five decimes (or 50 centesimi) were due at the post office when it was picked up there.

The rate between France and Sardinia was based on weight and distance in 1858. The 50 ctm per 7.5 grams was applied to letters that did not qualify for the border rate. Since Nice was much more than 30 km away from Nice using straight-line distance, it required the full foreign mail rate (Jul 1, 1851 - Dec 31, 1860).

And, Algeria was French

For the purposes of a postal historian, Algeria was simply a part of France in 1858. Beginning January 1, 1849, Algeria used the same postage stamps as France and they qualified for France's internal mailing rates. For example, if someone in the United States mailed a letter to Algeria in 1863, it would have cost the same as a letter mailed to Paris. For the purposes of our letter, that meant a location in Algeria could mail something to a location in France for the same cost as any internal letter anywhere in the France proper.

Above is an 1854 folded letter from Bône (now known as Annaba) to Toulon, France. Toulon is located between Marseille and Nice. The internal letter rate for France was 20 centimes for the first 7.5 grams of letter weight. So, even though this letter AND our merry chase letter had to cross the Mediterranean Sea, it still only cost 20 centimes for the first 7.5 grams in letter weight.

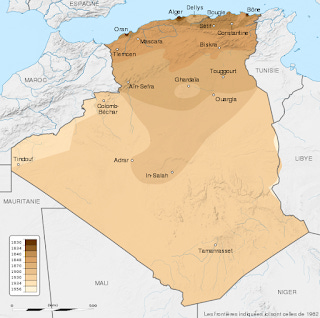

The French conquest of Algeria began in 1830, and for those interested in a visual timeline, you can click on the map above (from wikimedia commons) to get some idea of the progression. The wiki page for French Algeria feels like it is a summary of Ben Kiernan's work, which I will cite at the end of this blog. [2]

A single incident involving merchants who would not pay a bill, a French consul who was probably intent on siding with them, and ... a fly whisk... is cited as the cause of the war that followed. I think we can be certain the motivations were likely more complex than that. By the time we reach the year 1875, an estimated 825,000 indigenous Algerians had been killed in the war.

Knowing some of the history of French Algeria actually helps us to understand why a letter might be mailed from Philippeville (now known as Skikda) to Lyon in the first place. Beginning in 1848, France administered Algeria as if it was simply another département - a rough equivalent to a state or perhaps county in the US. People had been emigrating to Algeria from France and taking advantage of land confiscated by the French government from the native peoples there. By the time we get to 1858, and the mailing of our merry chase letter, the majority of people residing in the coastal cities of Algeria were actually Europeans who had emigrated there.

That seems to be as good as any reason that a person who lives in France might receive mail from someone in Algeria.

----------------------------------

Thank you for joining me for what started as a fairly simple Postal History Sunday and turned our to be quite the merry chase. I hope you found something to enjoy and that you learned something new in the process. Have a great remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

[1] Kellaway, Peter and Mizrahi, Eli, Bio of Jean-Louis Brachet in chapter 2 titled The Beginnings of Pediatric Neurology: the Early 19th Century, Child Neurology: It's Origins, Founders, Growth and Evolution, 2nd edition, Ashwal, Steven, ed., Academic Press, 2021, p 25

[2] Kiernan, Ben, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, 2007.