Borderline Benefits - Postal History Sunday

Welcome once again to Postal History Sunday on the Genuine Faux Farm blog! Take a moment and throw those worries into the kitchen scraps bucket and take them out to the chickens. Chickens don't seem to have many worries, so maybe they can handle them a bit better than we can.

Now that the chickens have something to peck at, let's take a look at some things I enjoy and like to share with others. Maybe you can also enjoy some of what I learn when I work with these things and you could learn something new too. Sounds like a good deal to me!

Internal Letter Mail vs Foreign Letter Mail

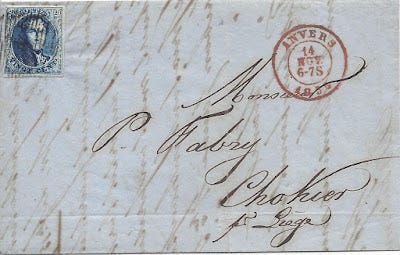

I thought I would start with a basic letter from one town in Belgium to another town in Belgium. As a postal historian I refer to this as either "internal letter mail" or "domestic letter mail." This folded letter was mailed in November of 1855 from Anvers (Antwerp) to a small town near Liege. The price for mailing this item was 20 centimes.

Internal letter mail rates in Belgium at that time were based on both weight and distance, but I don't want to distract from the point I am trying to make here, so I'm not going to talk about the distance factor. The cost of a letter weighing no more than 10 grams was 20 centimes for this distance.

Foreign letter mail, on the other hand, required the interaction of two postal services in order to get a letter to its destination. Each postal service was concerned that they receive compensation for their services and the postal agreements in the 1800s (until 1875) were often quite complex. In fact, there were several countries that failed to have postal agreements with some of their neighbors.

When there was an agreement, you would typically get something like this:

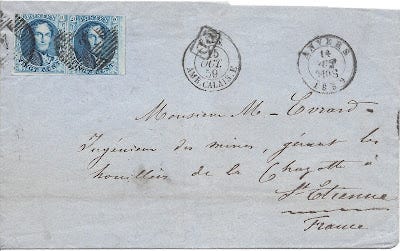

This is a another folded letter that started out in Anvers (Antwerp) in October of 1859. If you would like to learn more about this particular letter and the addressee M. Evrard, you can take this link.

You might notice the Anvers postal marking at the top right for Oct 14, which was applied by the post office in that city. There are two markings in the top center. One is the P.D. marking we talked about in this October 2020 Postal History Sunday entry. We learned there that the box with the "P.D." tells us that this item was "payée à destiné," which translates to "paid to destination."

The other marking reads "Belg. Amb. Calais E" around the outer ring of the circle. This is an "exchange marking" that shows where the letter left the custody of the Belgian mail service and entered the purview of the French mail service. In this case, the transfer occurred on a mail car on the train that went from Calais to Paris in France.

To be perfectly clear, it is possible that the mailbag left the custody of the Belgian mail service and was in French hands before this point. But, the marking shows when and where the mailbag was opened and processed by the French. It is at this point that the item officially entered their ledgers (so to speak).

The cost of this letter was 40 centimes for every 10 grams in letter weight. The December 1857 postal agreement between these two countries dictated that distance would NOT play a role in the cost of a letter - with one important distinction.

Neighbors in Different Countries

Could you imagine living just a couple of kilometers from the border between France and Belgium. You have friends who live just down the road, but that is officially in another country. You do business with people in the next town over, but they too live in another country. How would you feel if you had to pay 20 centimes for a letter destined to someone 5 kilometers to the North and then pay 40 centimes for a similar letter to someone 1 kilometer to your South just because they were on the other side of the border?

There were plenty of business interests in southern Belgium and northeastern France and there was likely plenty of pressure to recognize this issue. The postal agreement provided for a discounted rate if a piece of letter mail crosses the border and distance is 30 km or less from origin post office to destination post office. The distance for the letter above from Courtrai (Belgium) to Lille (France) is right around 30 kilometers, so this letter qualified for the reduced rate.

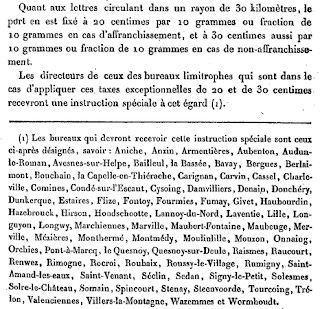

Actually, the agreement made it even easier for postal clerks to be able to determine what destinations qualified for this reduced rate. The postal convention listed the locations of post offices that qualified (you can click to see a larger version of the picture). This excerpt shows the French post offices.

As a result of this agreement, neighbors who wanted to mail things to someone in another country wound up paying the same rate as the first letter that was internal mail and half the amount the second piece of foreign letter mail required.

The Dutch and the Belgians

The Netherlands and Belgium had similar arrangements for border settlements. Shown above is an 1868 letter from Bruxelles (Brussels) in Belgium to Vlaardingen in the Netherlands. The rate for mail from Belgium to the Netherlands was 20 centimes for every 10 grams in weight. There was no distance component to the mail rate between these two countries at this time other than the special border rate.

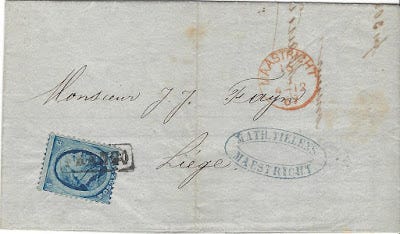

If the origin and the destination were close by, this rate was cut in half! The 1869 folded letter shown above only has a 10 centime stamps for an item mailed from Liege, Belgium (yep, that marking is hard to read!) to Maestricht in Holland. You will notice that, even though these letters traveled a short distance, they still have a PD marking to indicate that the postage was paid for a letter between nations. This may have qualified for a reduced rate, but it still had to be processed as a piece of foreign letter mail.

An interesting thing that I have noticed as I look for items like this is that these reduced rate items are far less common than the regular rates between these countries. And, because they are less common, it is more difficult to find examples that are nicer looking.

But, why would these be less common? It's a simple matter of mathematics. Without doing actual calculations, it would be safe to say that less than 5% of the population for each country lives inside of the area that could qualify for the reduced rate. On top of that, not all of the mail leaving those areas would go TO a destination that also qualified for the reduced rate. I think it would be safe to estimate that no more than 1% of all of the letter mail that was sent between Beligium and France or 2-3% for Belgium and the Netherlands would have qualified for these rates.

Huh. I think that explains it!

But, sometimes you are lucky enough to find things that others don't. Here is an example of a border letter rate from the Netherlands to Belgium in 1867. Each Dutch cent was equal to two Belgian centimes. So, it cost 5 Dutch cents for a border letter. You might notice that stamp has a marking that reads "Franco," which happens to be Holland's preferred marking to indicate a letter was paid.

Know A Good Thing When You See It

It isn't hard to understand how the idea of border rate reductions, once it showed usefulness in one agreement, would start popping up in other agreements. The root of these special rates probably comes from the fact that most postal services included distance as an element for determining postal rates. The further something had to travel, the more expensive it became. That certainly makes sense if transportation is your biggest expense.

If anything, the idea that the rate would stay the same for all distances EXCEPT border mail was the innovation that was a response to improved transportation via the railways.

Here is a folded letter mailed in 1862 from Switzerland to France. The normal rate to mail an item was 40 rappen for every 7.5 grams, regardless of distance. You will notice the exchange marking in red shows that control of the letter was transferred at Pontarlier (France). France and Switzerland both used the PD markings to show the receiving nation that the letter was fully paid.

And here is an 1860 letter that shows a PD marking and a red exchange marking at Fernex (France). The letter was mailed in Geneva, which was just across the border from Fernex (Ferney). Clearly, this is a situation where a border rate should apply, and it does. Only 20 rappen (1/2 the normal rate) was required.

If Ferney sounds familiar to some of you, you might recognize it better as "Ferney-Voltaire." The philosopher, Voltaire, purchased the land around the small hamlet of Ferney in 1759. Once travel is restored, you could go visit his chateau and the community that is part of Voltaire's legacy.

So, How Do You See It?

That brings me to the last point. How does a person, such as myself, notice that a letter could qualify for the borderline letter rate - no matter what pair of countries and regardless of the time in history?

The first thing is that I need to know what a normal piece of internal letter mail for the time period looks like.

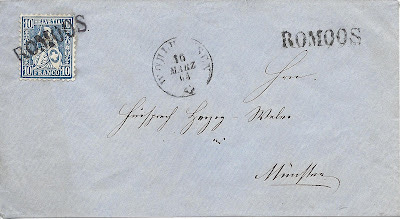

This internal letter in Switzerland was mailed in Romoos. It cost 10 rappen (or 10 centimes) to mail and the markings on the cover simply show its travels inside the country.

Most internal letter mail in Switzerland during this time period will have a 10 centime/rappen stamp. So, if I were to see a letter with that stamp, my first assumption is that it is a piece of domestic letter mail.

And here is an 1867 letter from Horgan, Switzerland, to Genoa, Italy. The rate between nations was 30 centimes/rappen per 10 grams and a PD marking was put on the letter by the Swiss to let the Italians know that they did collect the proper amount of postage. All in all, this is a pretty normal looking letter between these two countries for that time period.

So, I bring you this one:

This one was mailed in Splugen in 1865 and has a Swiss 10 centime/rappen stamp applied on it to pay the postage. The person who offered this item for sale listed it as a piece of "domestic letter mail" because that is what most 10 centime blue stamps in Switzerland were used for.

What told me to look closer?

You can see it too - it's the PD marking on the cover. Most post offices during that time did not use a PD marking unless it was a piece of foreign mail. That is not always true. The Netherlands used the "Franco" marking on internal mail as well as foreign mail. But, it was enough to make me look closer at this item.

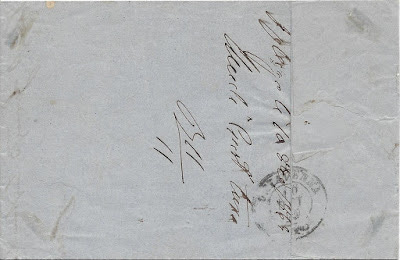

Splugen is both a settlement and a mountain pass in the Alps near the Swiss/Italian border. The hard part was trying to figure out the destination. The address panel on the front maybe reads "Clafau" or "Clafen," but I couldn't be sure.

The reverse shows a receiver postmark for Chiavenna, which is located just South of the border, which clearly makes it a piece of border mail. After some searching, it turns out Chiavenna is also known as Claven, Kleven and Clavenna depending on the language. It is just another case where the spelling of a location could be different depending on the person's background writing the address. We could talk about that more, but I think that could be a Postal History Sunday all its own.

Thank you for joining me this week. Next week's Postal History Sunday will be titled Turn, Turn, Turn. I believe that's called a "teaser" to increase interest for what's coming next. I wonder what it could be that I'll be showing you next time?

Until then, I hope you have a wonderful remainder of the weekend and a positive and fulfilling week to come. Maybe you had a chance to relax for a few moments today and you learned something new. If you have questions for this or past blogs or suggestions for future PHS blog posts, feel free to send them my way.

-----------------------

Further reading if you have interest:

Here is a post that I constructed regarding the mails between Switzerland and Italy. It needs another edit to update my knowledge there. But, it is fairly accurate.

Similarly, here is Switzerland and France and France and Belgium.

Each of these posts on the GFF Postal History Blog were created as a place for me to work on my own understanding of how these mails worked. As I continue to learn, I try to take time to edit each so that they are as accurate as I can make them.