Building Knowledge

Postal History Sunday #192

Another week has come and gone. Well, it’s not completely gone if you are among those who consider Sunday to be the last day of the week (anyone here prefer the ISO 8601 standard?). On the other hand, if you prefer the Judeo-Christian structure where Sunday starts the week, the view from here is different. The past week is gone and we’re about to embark on a whole new unit of seven days.

Regardless of your opinion on that matter, we are going to embark upon a new Postal History Sunday for your reading pleasure. Once again, I remind you that I am writing for a broad audience that includes individuals who have years of postal history experience and others who are merely curious. Usually, I can find something interesting to share for those who identify on each end of that spectrum and everyone in between. You are welcome here and I hope you will take a moment to relax and enjoy as I share something I like.

And maybe you’ll learn something new too!

Starting at the Beginning

I noticed the 1875 cover, shown above, because I knew that J. Monnier and Company was a French seed company. My background in small-scale, diversified farming attracted me to it, even though I was not familiar with French postal rates. That meant my little foray into French seed companies was going to require that I climb a new learning curve to understand it.

My first area of expertise within postal history is mail in the 1860s from the United States to Europe. I’m not sure I would count my partial understanding of other postal history topics as “expertise” prior to that. And, I am not certain if it is possible to identify the point at which I felt even remotely comfortable to claim this expertise. Though, I think I got an inkling that I might be able to hold my own when I suggested (cautiously) that another person with experience in the field might have interpreted something incorrectly.

And after a brief online discussion. They ended up agreeing with me. Usually a good sign that you’re going the right direction.

Now, imagine how it felt when I put myself in the position of starting over with a new area of study. I had worked hard to gain competence in the area I knew. So, it was frustrating to realize that I didn’t even know what resources to go to for information.

Learning something new always takes a bit of courage and willingness to fight off disappointment when things don’t come easily.

The damn broke for French internal mail rates when I found two resources:

Richardson, Derek J, "Tables of French Postal Rates 1849-2011," 4th ed, France and Colonies Philatelic Society of Great Britain, 2011.

Lesgor, Raoul, "The cancellations on French stamps of the classic issues, 1849-1876", Nassau Stamp Co, NY, 1948.

The Richardson book provided me with tables that illustrated the postage rates for mail sent within France, so I was able to determine that this 1875 letter would have been subject to postage rates as shown below:

A simple letter could weigh no more than 10 grams and the cost would have been 25 centimes. So, my letter was a simple letter that illustrates the rate nicely.

If I compare this to internal postage rates for the US at the time, this felt like new territory. The postage rate in the US was 3 cents per half ounce - a nice linear progression. The French did not follow a linear progression until they got to heavy mail (things that weighed over 50 grams).

A slightly heavier letter, like the 1874 folded business letter shown above, would cost 40 centimes. The second rate level would apply if it weighed more than 10 grams, but no more than 20 grams. Effectively, the 2nd ten grams of weight only cost 15 centimes - 10 centimes less than the first ten grams.

Being a curious soul, I wondered why this progression made sense in the first place. It’s a common business idea to set a minimum cost (in this case - 25 centimes) for any letter. Each item is going to require a basic set of services to be provided by the postal service, whether it weighs 5 grams or fifty. Since the simple letters (the lightest letters) were the most common, it made sense to set their postage rate so that it would cover expenses.

However, when we get to heavier letters, there isn’t actually much difference between 10 grams and 20 grams in service rendered. The only difference is that the heavy letter contributed more to the overall weight of the mailbag.

To give you some perspective, a standard sized piece of today’s printer paper weighs about 4.5 grams. So, three sheets of today’s paper would require a second rate level with this scale.

The folded letter shown above was even heavier. It must have had some content enclosed in the outer letter sheet that has been removed prior to landing in my collection. There is a 30 centime postage stamp and a 40 centime stamp for a total of 70 centimes in postage. This tells me that it must have weighed more than 20 grams and no more than 50 grams. This cost the sender an additional 30 centimes beyond the 2nd rate level.

At this point, I’d like to consider how much postage was required per gram to illustrate the logic of this rate structure. A ten gram letter would cost 2.5 centimes per gram. A 20 gram letter cost 2.0 centimes per gram. And a 50 gram letter would cost only 1.4 centimes per gram.

So, we see the pattern here. The cost per gram was reduced - if you considered items that landed towards the top weight at the rate level. The deal isn’t so wonderful if a letter just barely exceeded the limit of the prior level.

If you had a letter that already exceeded 20 grams, you might as well send a few more things to take advantage of the third rate level as best you can!

Taking it on the Road

Once I got a handle of the internal postage rates for France in the 1850s to 1870s, I was ready to think about postage from France to foreign countries. Happily, J.L. Bourgouin has produced an excellent website that shows French postal rates for this period. Prior to discovering that site, I was looking for the postal treaties that set postage rates to give me ideas of what I was looking at.

This link will take a person to an online copy of a treaty book put together by M De Clercq (Recueil des Traites de la France:Tables generale 1713-1885 Index). Yes, it’s in French. For that matter, so is the website. But, what did we expect? It’s letter mail postage rates for France!

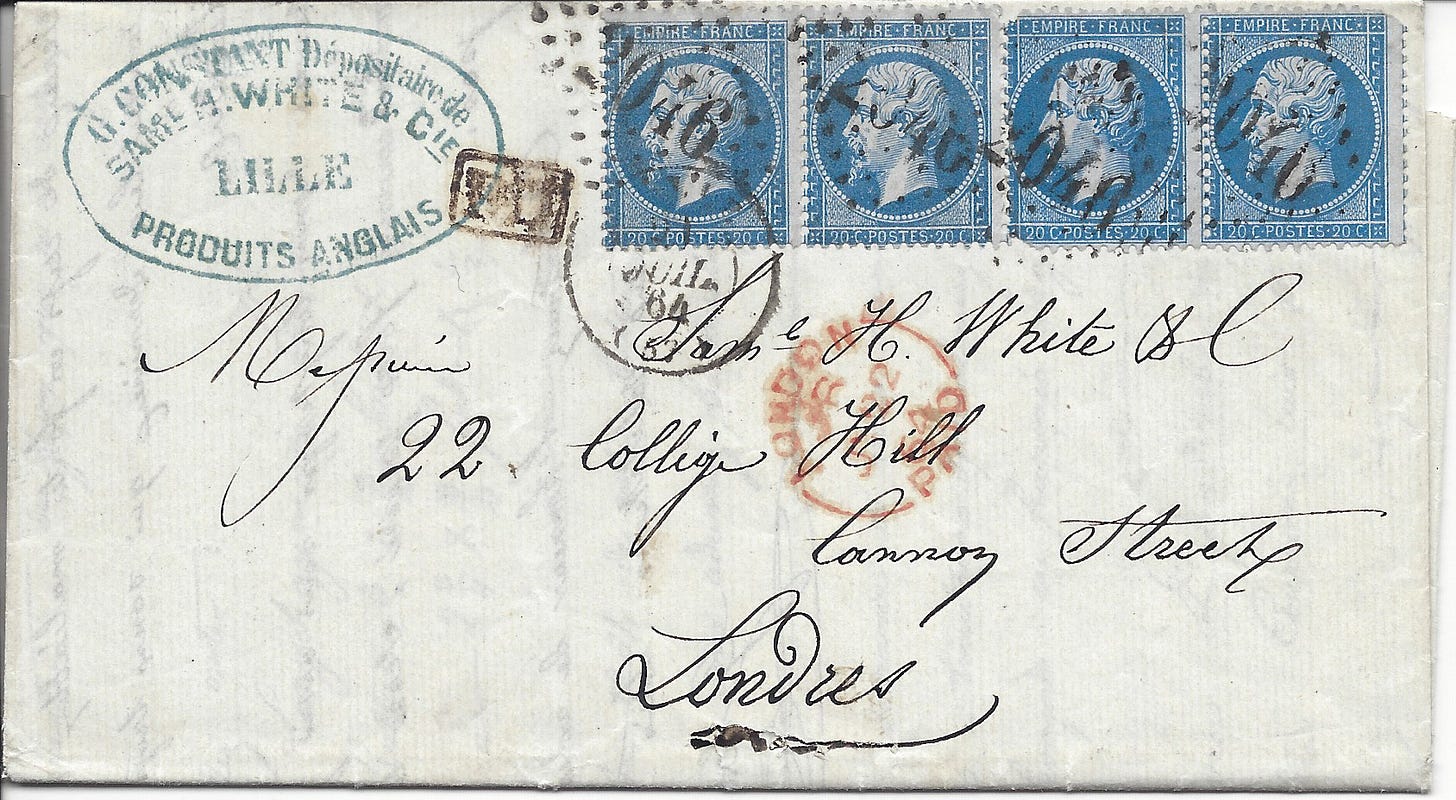

Our first letter is dated in 1864, so the postage rate would be 40 centimes per 7.5 grams. Unlike the French internal rate, this one follows a linear progression. So, our business letter must have weighed more than 7.5 grams and no more than 15 grams, making it a double weight letter, requiring 80 centimes in postage.

This second example of a letter from France to the United Kingdom was mailed in 1871. The postage rate was reduced in 1870 to 30 centimes per 10 grams. Not only was the cost per unit reduced, the size of each unit was increased. It’s pretty nice for business when the expense for communications goes down.

Once I was able to determine the expected postage rates for foreign letter mail, it got easier for me to identify what was normal and common. As that became familiar to me, I was then able to develop some skill in finding exceptions and oddities.

Finding Things That Are Different

Here is an excellent example of something that is different.

Like so many border covers, the postage stamp design we see here was used on typical domestic mail (or internal mail) for France. Simply put, there are lots and lots and LOTS of examples of folded letters and envelopes with this blue, 20 centime stamp on it. And, nearly all of them are a simple letter mailed from one place in France to another place in France.

So, the trick is to learn how to identify hints that what you are seeing is NOT typical.

The first and easiest clue if you are digging through a whole bunch of envelopes and folded letters from the 1850s, 60s and 70s in France is to look for the red boxed marking with "PD" (payee a destination - paid to destination). Postal clerks in France used this to indicate postage was paid when the letter was going to leave the country.

The other clue, of course, was the fact that the country name was included in the address (Belgique). That might sound simple, but we have to remember things like my Belgium (in English) is France’s Belgique.

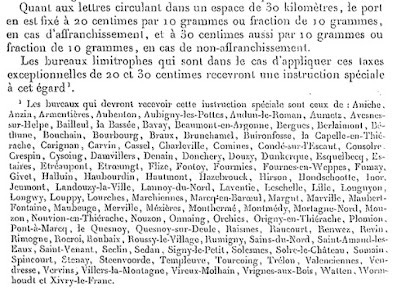

Shown below is text from the postal convention that was in effect as of January 1, 1966 between France and Belgium. It sets the border rate at 20 centimes per 10 grams in weight, instead of the 30 centimes for all other mail to Belgium from France. To be eligible the distance could be no more than 30 kilometers from the origin to the destination.

This document includes a list of French communities that were eligible for this reduced rate if the destination was within the 30 kilometer distance. The town of Anzin is the second one on the list - and that's where this letter came from.

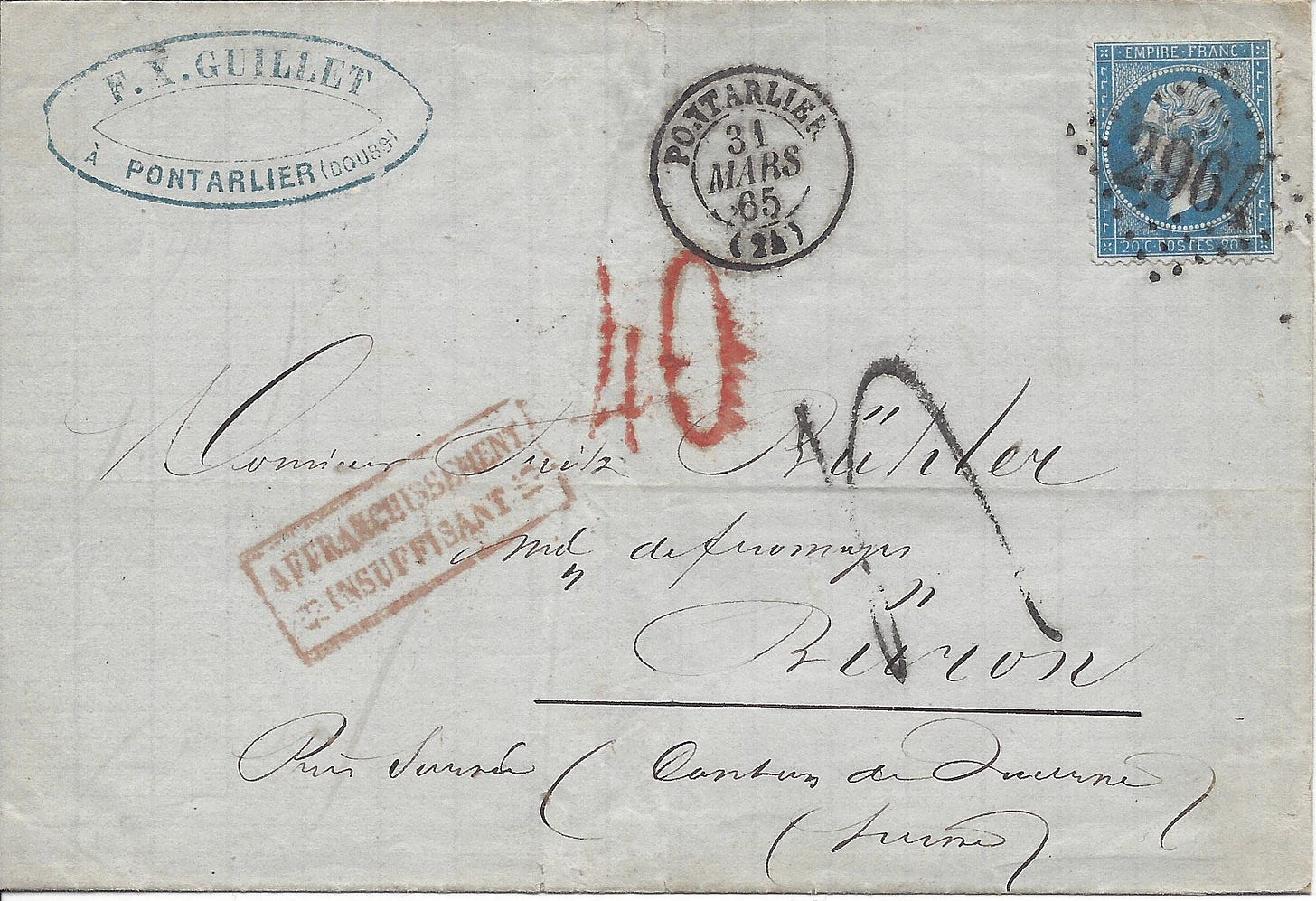

Then there are letters where not enough postage was paid, like this one sent from France to Switzerland. The required postage, in this case, would have been 40 centimes, but only a single 20 centime postage stamp was placed on the letter. As a result, there is no “PD” on this letter. Instead, there is a box with “Affranchissement Insuffisant” that tells us there is not enough postage paid. The big red “40” indicates that the Swiss post office needed to collect 40 Swiss centimes from the recipient.

At the time this letter was sent, many postal agreements between countries declared partial payments were to be treated the same as no payment at all. The 20 centime stamp was, essentially, wasted and the recipient had to pay as if no postage had been provided.

I don’t know about you, but I might have been a bit frustrated by this if I got a letter in the mail that was short paid and I had to pay for the whole cost.

So, why would the sender make this mistake in the first place?

The key might lie with the border rate letter I showed just before this one. Pontarlier, France, is right on the border with Switzerland. The sender might have been used to sending letters to Switzerland with the border rate. But, unfortunately for them, the destination for this letter was too far away to qualify for that rate.

Ooops.

I suspect a fully paid letter of apology might have been in order the next time they sent a letter to the same address.

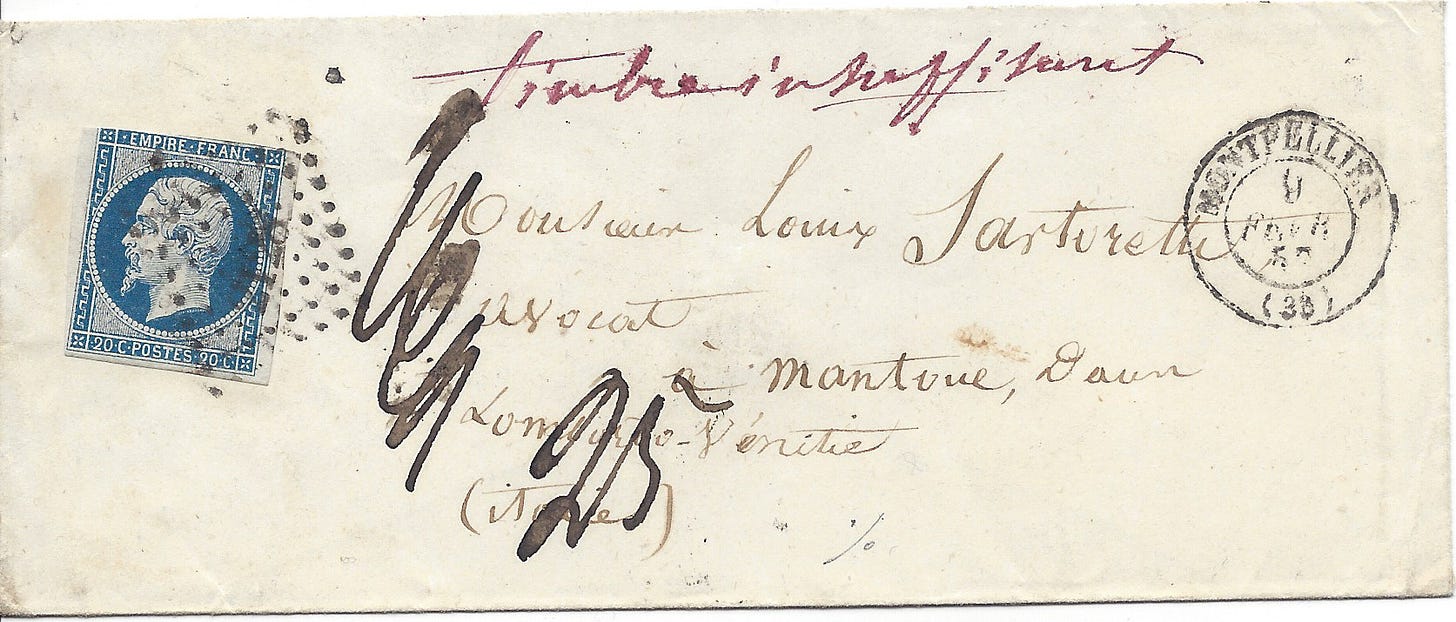

The cost to mail an item from France to Lombardy was 1 franc (100 centimes) at the time this next letter was mailed. However, the sender only applied a single 20 centime stamp to pay for postage, which was clearly not enough. Just like the last letter, part paid mail was treated as unpaid at the destination.

This time there is a hand-written "timbres insuffisant." That, and the absence of a "P.D." marking, made it clear that this item was not fully pre-paid.

Monsieur Sartoretti was forced to pay 25 kreuzer - the full price that it would cost for him to mail a letter from Mantova to Montpellier, France. As a lawyer (avocat), I would not be surprised if Sartoretti billed the postage due to his client later on.

Then there are these scribbles. More often than not, markings like these on covers prior to 1875 usually hold some significance for postal historians AND the postal clerks who handled this mail. As most people would guess, the "25" at lower right is the due marking, instructing the carrier or clerk to collect 25 kreuzer to pay for the mail services from France to Lombardy via Sardinia.

The smudged scribble on the left reads "16/9."

Yeah. I know. It seems like some sort of voodoo magic when I tell you a scrawl on one of these old envelopes means something. It is possible that many of you saw this scribble and figured someone was trying to draw a picture of a bird in a tree and gave it up as a bad job. This is one of those times you might have to trust that I know what I'm doing. Give it time. After a while, you'll start seeing scribbles in your sleep. Soon after that you should be able to see what I am seeing.

We'll all have to decide at that point whether this is a good or a bad thing.

The amount of postage collected was 25 kreuzer, of which 9 kreuzer covered the Austrian postage (the lower number). The remaining 16 kreuzer needed to be given to the French and Sardinian mail services. Of those 16 kreuzer, the French received 12 kr and the Sardinians 4 kr.

As for the 20 centime stamp? Well, it really did not do anything, in the end. This was not an uncommon occurrence at the time. Postage stamps were first introduced in France in 1849 and the idea of full prepayment for letters and using stamps to represent that payment was still kind of new.

Simply put, people didn't always understand what they were supposed to do. And when they made mistakes, the provided future entertainment for postal historians like me! And, by proxy, you!

Bonus Material - J. Monnier & Cie

Let me bring you all back, full circle, to the first letter I shared in this post.

It was addressed to J. Monnier & Cie, La Pyramide, Trelaze, Maine & Loire.

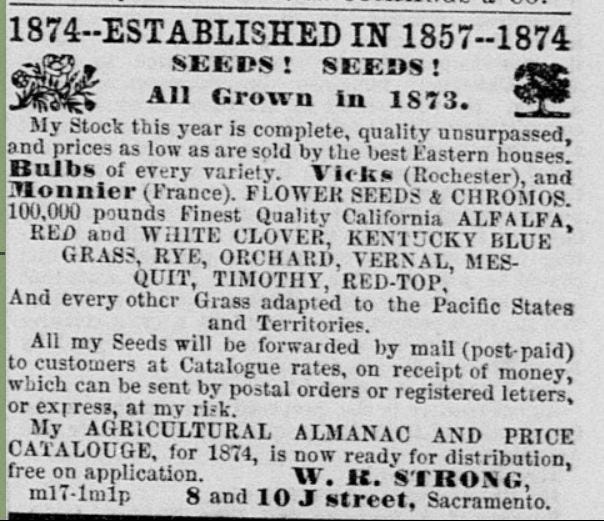

J. Monnier and Company was a well-known seed house that sent catalogs to prospective buyers. As you can see from the advertisement shown above from California in 1874, just one year prior to the cover I highlighted, J.Monnier shipped seed internationally. In fact, they were big enough to sell their seed for retail, which was the case with W.R. Strong in Sacramento.

Now, I could go off on a tangent and discuss how commercial interests like these have often been the drivers that have led to invasive species around the world. But, I won’t. Not today anyway!

Trelaze is located to the immediate southeast of Angers and La Pyramide is still a commercial area in Trelaze. While I was unable to find an image that was contemporary to this piece of postal history, I was able to find an image of a postcard depicting La Pyramide as it looked in the 1920s.

Maine et Loire is a department (roughly equivalent to a county or state in the US) that is named after the two main rivers in that area of western France.

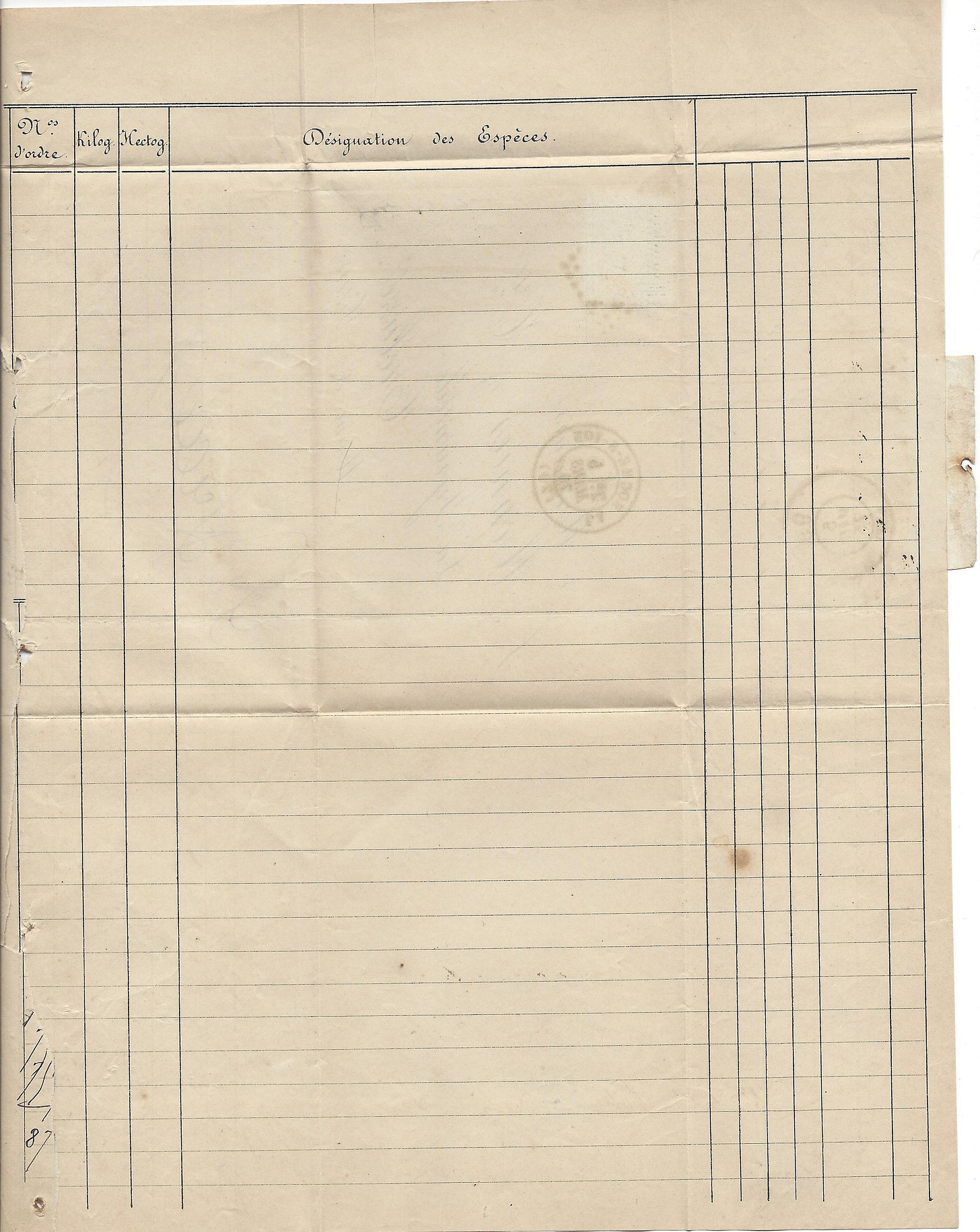

The contents that remained with this cover included a catalog order form. Those of you who still get printed garden and seed catalogs are witness to much the same thing every spring. The catalog comes and there is an insert with a grid to order the seeds you would like. Often, there is a pre-addressed envelope included, just like the one that makes up what is now an interesting piece of postal history for me.

There is one more bit of interest with the first cover that I think is worth pointing out. There is a different sort of postal marking on the back, which is shown above.

This is known as a Bureau de Passe marking. First instituted in 1864, twenty-five offices were placed at key railway junction stations for sorting and dispatching mail. The Bureau de Passe number is situated at the top of the double circle marking (99 - Angers) and the department number is at the bottom in parens (47 - Maine et Loire).

And there you go! Probably more detail than anyone really wanted about things you didn’t know you might enjoy knowing. My job for the week is done.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

As a lover of postal history, who is also short on time, I asked myself, "How can I wade through all this detail?". Yet every word had my full attention. Thank you for your efforts and for sharing this window into the past!