Welcome everyone! This April weekend in Iowa is going to be much warmer than usual, so I hope to spend some time outdoors. That often means I have to get ahead of the game with my writing because I can’t rely on having time on Saturday to complete the task.

The good news for you is this: if your Sunday is busy, you can still enjoy Postal History Sunday on any day of the week. Whenever it is that you find time to join us, make sure you take those troubles and worries and pretend they are a sheet of paper. Fold that paper in half as many times as you can until it's really, really small! Then, flick it to the floor so the cat can play with it. It won't take long before you can't find those troubles anymore (until you decide to clean under the fridge).

It Doesn’t Have to be Spectacular

The beauty of postal history is that a person does not have to expend exhorbitant amounts of money or wait for a truly amazing item before enjoying the process of discovering a story. This week, I wanted to focus on a cover that, while it is nice enough, probably would not immediately grab most collectors’ attention.

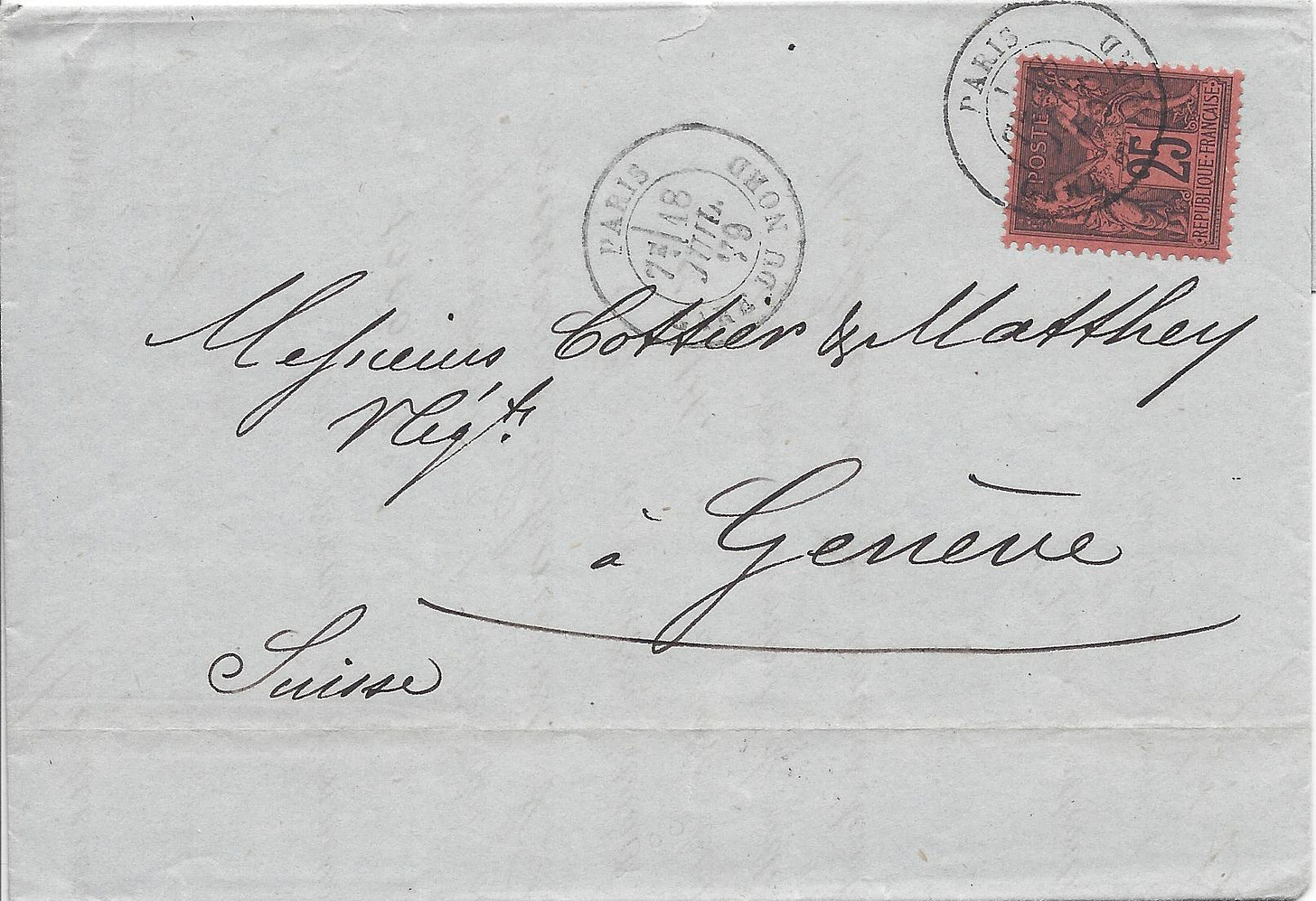

This is a simple business letter that was sent from Paris, France to Geneve (Geneva), Switzerland, in 1879. Like many of the business letters of the time, the content was simply folded over on itself for mailing, no envelope was used. Postal historians refer to these as folded letters or folded lettersheets (we can be so clever sometimes!).

This cover is actually newer than many of the things I collect. Yes, it seems odd to say it is newer and then point out that it is from 1879, but it is nonetheless true. Most of the items that interest me are mailed prior to the mid 1870s because I like exploring all of the individual postal agreements between countries. After 1875, the General Postal Union (GPU) set standards and postage rates between many nations of the world. And, by 1879, the GPU had become the the Universal Postal Union (UPU) and most nations were members. That means this letter was sent using UPU rates and procedures.

This letter was mailed at a rate of 25 centimes for every 15 grams and a 25 centime postage stamp is cancelled on the folded letter at the top right to show the amount was prepaid. It was sent from the Gare du Nord post office in Paris on July 18, 1879 and it was on a train in Switzerland the next day. There is no specific marking telling me when the Geneve post office accepted the item for delivery, but it is pretty safe to guess that it was in Geneve on the 19th.

For this particular piece of mail, we have a postmark on the front for when the item was brought to the Gare du Nord on July 18. Well, actually, we have that same marking twice. One is used to deface the postage stamp so it can't be used again and the other is on the envelope. I suppose the second strike is so the recipient can see when the French postal service got the letter for mailing.

In case you are curious about it, Gare du Nord was (and is) a train station in Paris that served as the terminus for the Paris-Lille railway run by the Chemin de Fer du Nord (Northern Railway). The train station building being used at the time would have been the second such building with this name. The first being replaced by this one in 1865. This train station is still in service as of this writing and can be seen below.

Traveling Post Offices

As international mail became more standardized and the number of mail train routes increased in France and Switzerland, the postal services also simplified the markings they put on each item of letter mail.

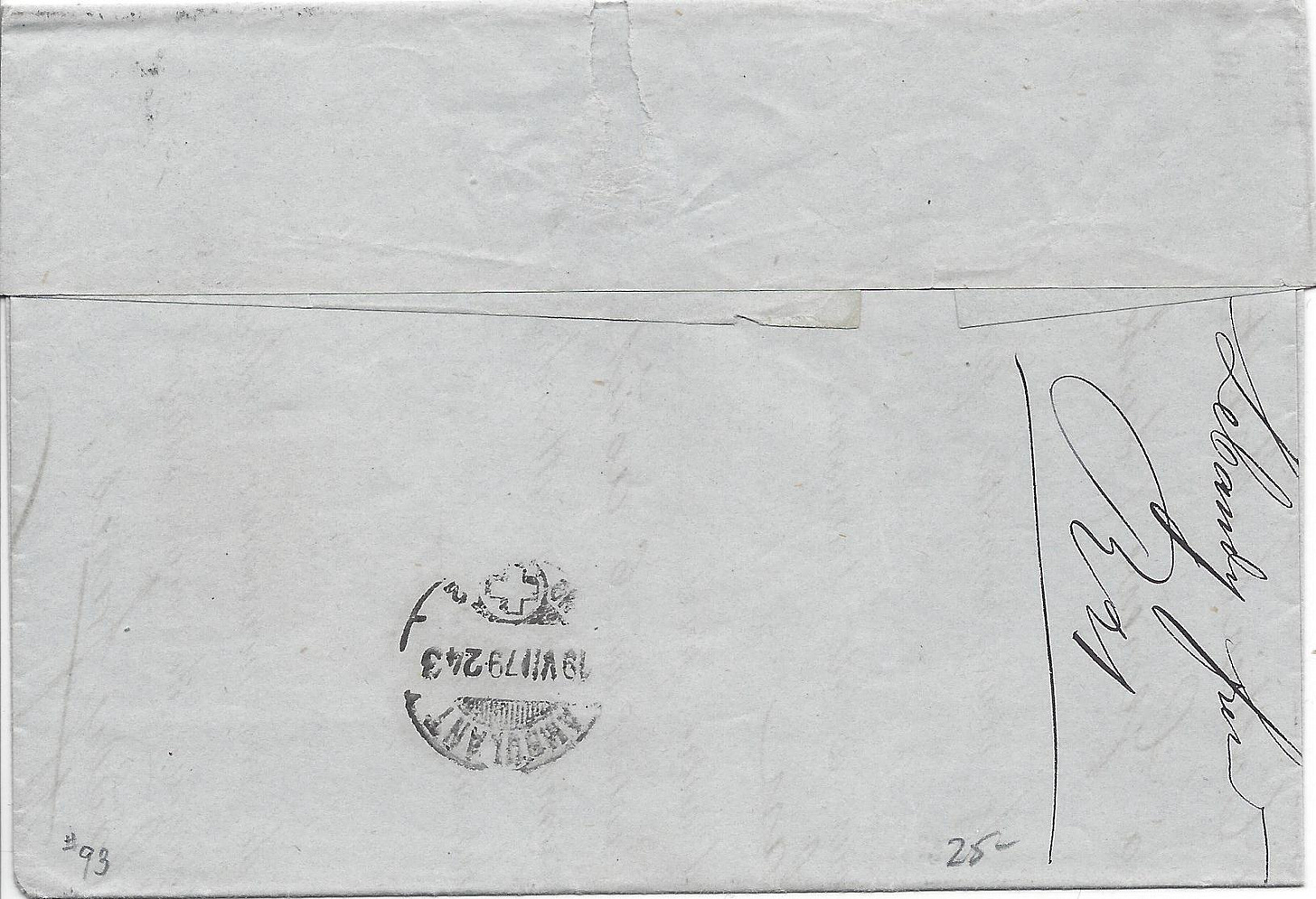

Other than the two postmarks on the front, the only other postal marking is the ambulant marking on the back.

The marking on the back of the letter reads: Ambulant 19 VII 79 243 No 2.

The first three parts are the date (July 19, 1879) and the rest identifies the train and maybe the postal clerk (does anyone have information on this?). The only clues we have for the routing of this mail are that it was mailed at the Gare du Nord post office in Paris and that it was on this train in Switzerland. Otherwise, we can’t be entirely certain what route it took between these two locations.

This is, perhaps, one of the reasons I take a little less joy in mail after 1875 - there is so much less for me to read on each piece of mail! There were numerous possible routes for it to get from here to there and we have fewer clues to help us take that journey.

But there is still plenty to explore! If there weren't we wouldn't feature this item on Postal History Sunday, would we?

An ambulant marking is also known as a marking for a Traveling Post Office (TPO). Most trains that carried the mail had a mail car with a clerk who had the duty of processing mail and making sure it off-loaded at the proper train stations. And, yes, they were also responsible to taking on additional mail at each stop.

If this interests you, the Smithsonian's National Postal Museum has an excellent online article that shows how a mail clerk in the United States was able to snag mailbags without the train stopping! Their European counterparts had similar techniques for delivering and receiving mailbags from locations where the train was not scheduled to stop. The photo above shows a clerk snagging a mail bag (look closely for the hook and the mailbag by the doorway).

Lebaudy Freres

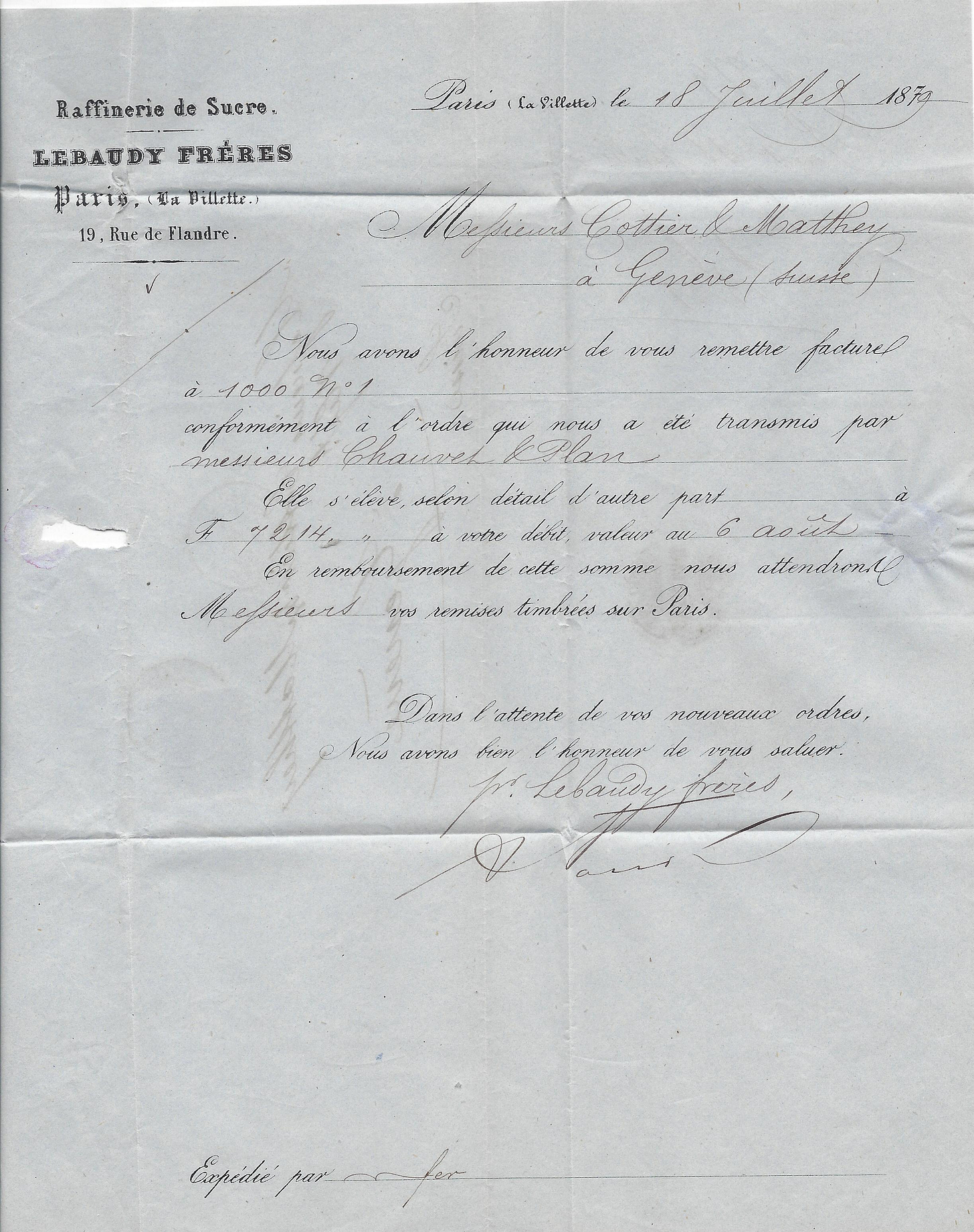

The folded letter contains an invoice for product (refined sugar) sold to Cottier & Matthey in Geneve.

Lebaudy Freres (Gustave and Jules) were a very large and successful Sugar Refinery that was located north of Paris. The two brothers made a significant fortune. Some information I picked up as I read about this business suggested that there may have been a number of dubious practices with respect to their workers. Another odd little fact that came to light was that their company used a significant amount of gas for their refinery operations.

Gustave was apparently the head of the company and also an elected member of the National Assembly from 1876 to 1885. He was linked to the death of Leon Gambetta in 1882 - though I do not know if this was deserved or not - and he lost re-election in 1885. However, he was again elected in 1889.

Without knowing the details of the situation, it is tempting to point to this as an historical example of the short attention span the public often has when it comes to political figures. One could claim that it was possible that he was never linked to Gambetta's death and the public was now informed of that truth - but it is more likely that the public had simply moved on from the prior scandal.

(information from Henry Coston, "Dictionary of the bourgeois dynasties and the business world" - Editions Alain Moreau, 1975, p.343)

The Generations that Follow

Gustave had two sons who apparently took over the business. These two decided that they would expand into the building of semi-rigid airships (zeppelins or blimps). The sugar refinery business continued until 1960 when it was purchased by rival Sommier, but it seems that Gustave’s two sons had plenty of energy for the airships and probably left the running of the refinery to subordinates.

In any event, Paul and Pierre Lebaudy worked with engineer Henri Julliot to build a dirigible that ended up being purchased by the French military in 1904, only a couple of years after they proved its abilities with a first flight.

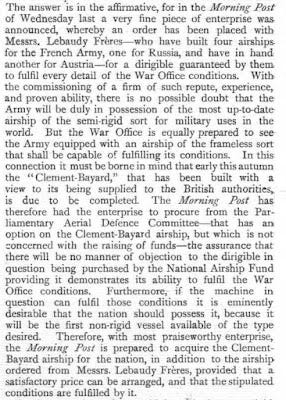

The publication "Flight" of July 24, 1909 reported that the British government was looking to add dirigibles, including the possibility of ordering some from the Lebaudy brothers. This article reports that the French and others were already in possession of airships developed by them.

It might be tempting to presume that most of the rigid airship development in the early 1900s focused around the German Zeppelins (like the Hindenburg) that were so prominent in the 1930s. However, there was concurrent development in France, the United Kingdom and the United States during this period as well. The Lebaudy airships are often overlooked in summaries of airship development, but they were, apparently, able to make some sales.

Mad Jacques

Gustave might have been proud of his sons' accomplishments in air technology, but I wonder if Jules would be as pleased with his son? Jacques took his sizable inheritance and became the subject of no small amount of mockery. In 1903, he recruited 400 mercenaries and claimed a piece of Morocco (near Cape Juby) as his new "Empire of the Sahara."

The photo below was taken from this blog article by Darren D'Addario, featuring an old print article on Jacques Lebaudy.

Jacques made a "royal visit" to London later in 1903 and was lampooned by PG Wodehouse. This Emperor's Song was published in the Daily Chronicle on October 2, 1903.

The following is the content in the Chronicle:

M. Jacques Lebaudy, “Emperor of the Sahara,” arrived in London on Monday for the purpose of purchasing agricultural implements for his colonists, and is staying at the Savoy Hotel, inaccessible to interviewers and tradesmen. “His Majesty” has been out on several occasions, but always contrives to escape observation.]

The lot of an emperor is one

Your comfort-loving man should shun;

It’s wholly free from skittles, beer,

And other things designed to cheer.

There are worries small, and worries great,

Private worries and worries of state,

But the one that most distresses me

Is the terrible lack of privacy.

It rather tries my temper, for

I’m such a retiring Emperor.

In the Savoy I sit all day

Wishing people would go away;

Cross, disgusted, wrapped in gloom,

I daren’t go out of my sitting-room.

Every minute fresh callers call.

There are men on the stairs and men in the hall,

And I go to the door, and I turn the key,

For everyone of them’s after me.

Which is exasperating for

A rather retiring Emperor.

There are strenuous journalistic crews,

Begging daily for interviews;

There arc camera fiends in tens and scores,

Philanthropists and other bores,

Men who are anxious to sell me hats,

Waistcoats, boots, umbrellas, and spats,

Men who simply yearn to do

Just whatever I want them to.

Which causes me annoyance, for

I’m such a retiring Emperor.

Of course “the compliment implied

Inflates me with legitimate pride,”

But often I feel, as my door I bar,

That they carry their compliments much too far.

That sort of thing becomes a bore

To a really retiring Emperor.

Lebaudy and his family moved to the United States in 1908 and he became increasingly erratic, threatening the life of his wife and daughter on multiple occasions. In the end, it was his wife who ended his life and the authorities decided not to press charges against her. According to some sources, the tipping point was Jacques' insistance that he needed a male heir by his own daughter.

The story of Jacques Lebaudy and the Empire of the Sahara is actually a fairly easy one to track down as there have been multiple re-tellings that reside on the internet. A couple of the blogs listed in the final section also provide more detail regarding Jacques and his brother, Max (who died of tuberculosis in 1895), and the plight of workers in the sugar refineries.

Like Father Like Son?

Perhaps, the apple did not fall so far from the tree? Jules (Jacques' father) owned many properties in Paris and was known for stock trading manipulations that may well have contributed to a 'stock crash' in 1882. This crash led to a significant depression lasting to the end of the decade. In both the case of Jules (the father) and Jacques (the son), there was no lack of money and clearly plenty of desire to manipulate things to suit their whims.

(see White, Eugene, The Crash of 1882 and the Bailout of the Paris Bourse, Springer-Verlag, 2006.)

A New Hero - Saving the Best for Last

Perhaps bad can bring about good? My favorite story that comes from exploring this business letter happens to be that of Amicie Lebaudy, Jules' spouse (born Marguerite Amicie Piou, 1847).

Amicie wrote books under the pseudonym Guillaume Dall and engaged in some philanthropic activities while her husband lived. After the crash of 1882 and Jules' death in 1892, Amicie created (anonymously) the Groupe de Maisons Overieres (Workers Housing Group Foundation). Not only were affordable houses created, it was her goal to create a healthy 'habitat' for those who lived in them. The foundation is still in operation today.

Of particular interest is the statement on the foundation's site that Amicie wanted to avoid placing the name "Lebaudy" on the foundation because "Lebaudy was synonymous with money ill-gotten."

In the process of digging, I found this interesting blog post by Laurence Picot (in French) that also explores this family history, starting with Amicie.

From his post, we have this paragraph (translated to English):

"Today, in 2017, we stroll through the streets of Paris and we can identify on the facades of magnificent real estate groups the sculpted and anonymous woman who holds out a handkerchief or an olive branch to women, children, and the poor. Her foundation still exists and continues to build low-rent housing. There are 2400 units now, in Paris and the suburbs, and 86 workshops. About 6,500 people live inexpensively in spacious, sunny apartments with a style that one might consider classy."

Another useful online article by A Boutillon provides even more insight (also translated from French):

"In her retirement from Saint-Cloud, Amicie had begun to write. In 1893 she published, under the pseudonym of Guillaume Dall, a first work entitled "La Mère Angélique, abbesse de Port-Royal, her correspondence .” In the years that followed, she wrote seven or eight others, mostly essays and some children's' books. At the same time, having decided not to keep her husband's legacy, she became one of the greatest philanthropists of her time. She financed anonymously, her name not to be revealed until after her death, the purchase of land and the construction, between 1900 and 1905, of a new hospital for the Pasteur Institute, and provided grants for students without resources."

It is said that part of the motivation for funding the hospital was in response to her son Max's demise from tuberculosis. The photo of the statue comes from Boutillon's article which indicates that the bust is actually located at the Pasteur Institute.

I may have just acquired a new hero to add to my list of amazing people who have graced this good earth. Well done, Amicie. Well done.

Sugar refineries, business letters, airships, politics, scandal and good works. This Postal History Sunday may have outdone itself! I hope you enjoyed your time reading this entry and perhaps you learned something new.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.