By the Sheet

Postal History Sunday #224

I have been noticing a pattern that has been emerging and maybe you have too. Every seven days there is a Postal History Sunday article that pops into subscriber email inboxes at 5 AM (or a few minutes after). I wonder if it’s magic or just a coincidence? If anyone figures it out, let me know!

In the meantime, let’s set our troubles outside until they freeze into a solid chunk of ice. If you live in a place where that won’t work, maybe you can find a spot in your freezer. Once they’re ready, I think a judicious application of a sledge hammer just might be appropriate.

So, while we’re waiting for those bothersome problems to get cold enough to smash them with a hammer, let’s see if we can learn something new!

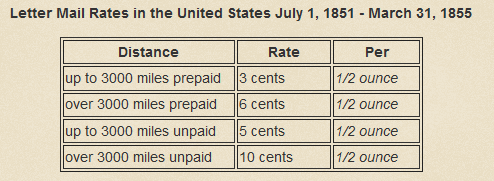

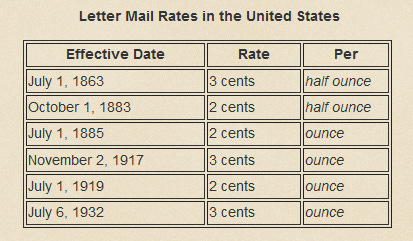

In last week’s article, we shared advertising covers that were farm related. Most of those pieces of postal history were sent during a time frame where the postal rates didn’t change. But, I did include a table with postage rates that apparently piqued the interest of a couple of individuals - one of whom is a self-identified “interested but never going to become a postal historian.” As a result, I had a couple of excellent questions regarding the postal rates in the United States in the 1800s.

One question was “How often did letter postage rates change?” The other, from a person who identified themselves as learning about postal history, wanted to know if I could share more US domestic letter postage rates. It just so happens that I wrote a very early Postal History Sunday on that topic that is in dire need of a re-write. How fortuitous!

And, yes, I’ve been looking for a chance to use “fortuitous” in one of these articles for some time now.

Determining letter size by the sheet

Postage has traditionally been assessed for letter mail based on two common variables:

how far a letter must travel to get to the destination, and

how big the letter is.

The thing that has changed over time is how postal agencies determined distance and size. For example, the Swiss divided the country into rayons (or regions). A letter mailed from an origin to a destination that was within the same rayon was given one postage rate. If the destination was in another rayon, it would require more postage. The French, on the other hand, based the rate on tiers of distance traveled. A letter that traveled 50 km would cost less than one that traveled 150 km.

In the early 1800s, the United States used a tiered system based on distance traveled. But, by 1863, the US had removed the distance component from their internal letter mail rates.

The size measurement also progressed from one method of measurement to another over time. In the early 1800s, the United States determined size by the number of sheets of paper that were in a piece of letter mail until an item reached one ounce (typically 4 sheets) in weight. At that point, weight was used to determine the required postage. As we move to the mid 1800s, the United States changed to a weight-based method of determining size. The number of sheets in a piece of letter mail did not matter.

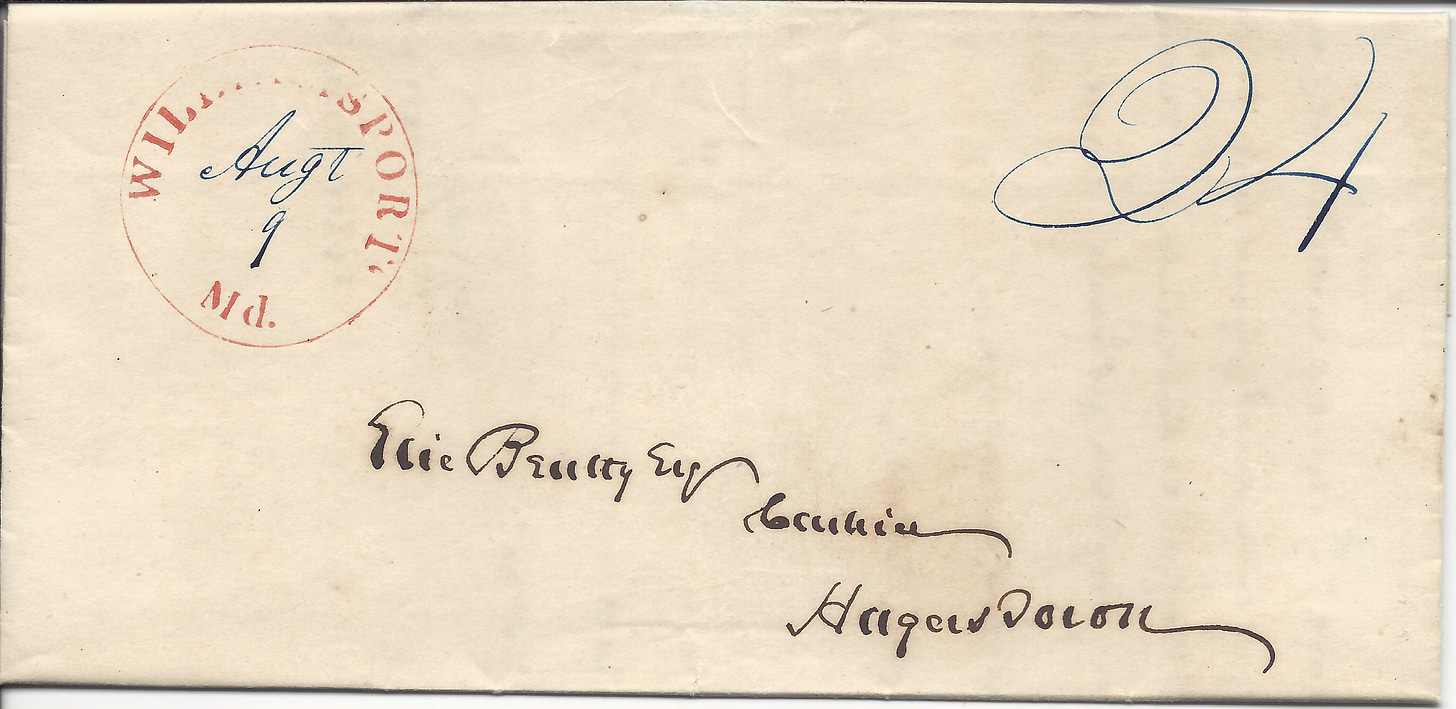

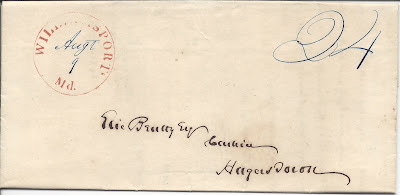

The folded letter shown above is dated August 9, 1839 and was mailed from the Washington County Bank in Williamsport, Maryland to the Cashier at the Hagerstown Bank (also in Maryland). To cut right to the chase, this letter had FOUR sheets (or it weighed one ounce), even though I currently only have one sheet with this item in my collection. That raises the question - how do I know there were four sheets?

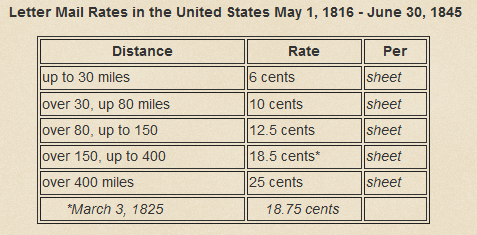

Well, here is the postage rate table for letters that includes the year 1839. This rate period lasted for almost thirty years with some adjustments in 1825.

The distance from Williamsport to Hagerstown was (and is) about 7 miles. A simple or single weight letter would require 6 cents in postage. This particular item has a nice bold "24" at the top right, which is four times the single letter sheet. Thus, we can deduce that this item had four sheets of paper total (including this outside wrapper) or that it weighed in at one ounce.

One sheet - Longer distance

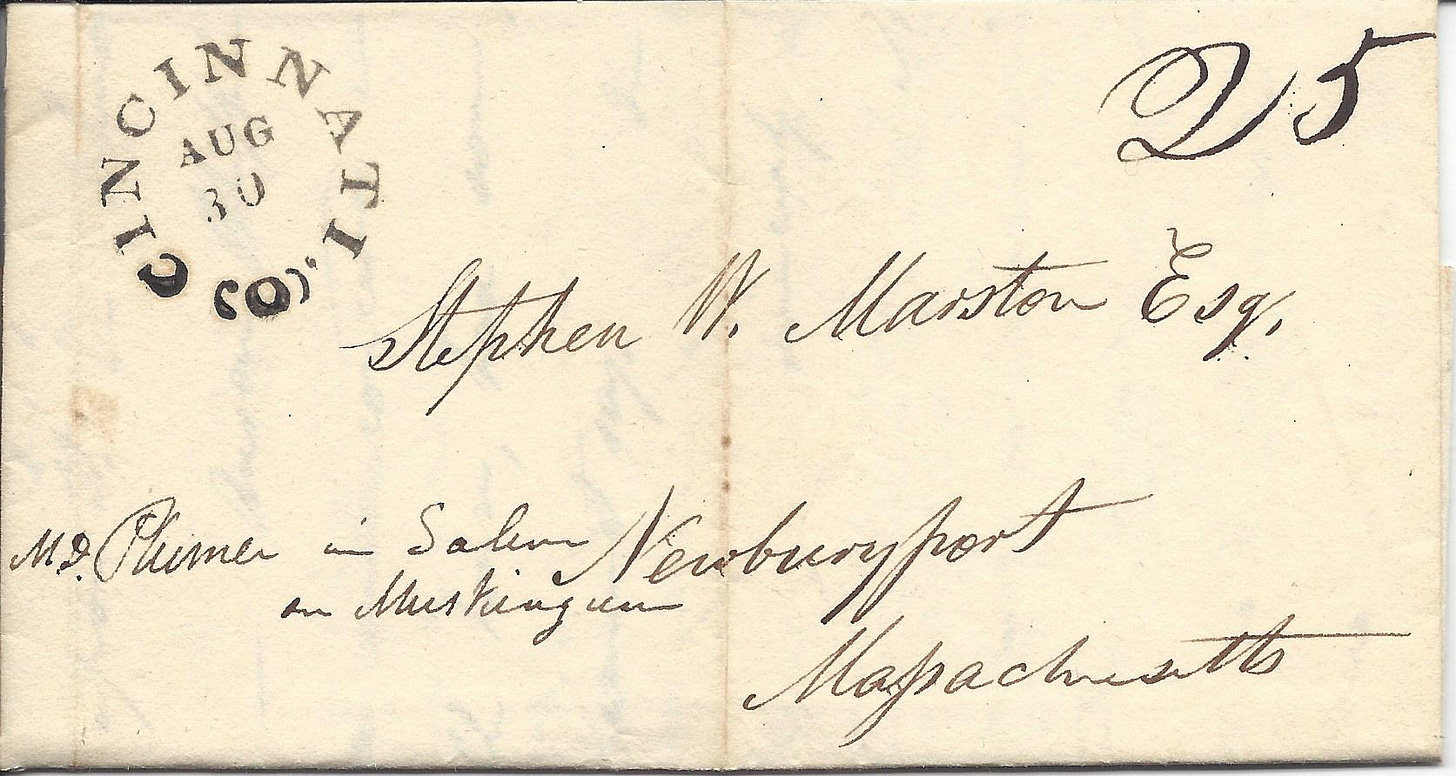

While I do not have many items from this time period (1816 - 1845) in my collection, I do have a couple that I can show here. The second must have been only a single sheet (the one that resides in my collection), but it traveled a much longer distance.

This letter was mailed on August 30, 1819 from Cincinnati, Ohio to Newburyport, Massachusetts, a distance of 915 miles (more or less). A clear marking reads "25" at the top left, which indicates the postage Stephen W Marston would have to pay for the privilege of receiving this missive. The rate per sheet was 25 cents if it traveled over 400 miles, so this qualified as a single or simple letter.

I have heard it said by some that the prevailing attitude in some cultures was that it would be offensive to prepay a letter because it might imply that the sender felt you could not manage to pay for your own mail. While I have no idea if that claim is accurate or not, I can accurately report that prepayment at this time was uncommon. The norm was to send letters unpaid unless some of the postage was required by postal regulations.

The winds of change blow - July 1, 1845

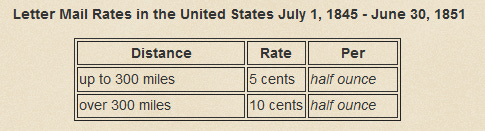

Things changed dramatically in 1845 when the United States ceased worrying about the number of sheets of paper and relied on the weight of a letter to help determine postage costs. I suspect you might be able to think of several reasons for this adjustment. First, how much time must it have took for a postal clerk to verify the number of sheets in a particular item? And, if they did, what happened if a sender wanted to close their letter sheet with a wax seal or use an envelope?

The US introduced a rate progression that made it easy to verify the amount of postage with a simple scale. With the new rules a letter that weighed up to 1/2 ounce would be considered a simple letter. Each half ounce (or portion of a half ounce) over that amount required another rate of postage. So, a letter that weighed 3/4 ounce would require a “double rate.” A letter that weighed over 1 ounce, but no more than 1.5 ounces, would require a “triple rate.” And so on.

The U.S. Postal Service was beginning to see more and more competition from private enterprise that was seeking to provide mail services to the public. The biggest difference-maker was that Congress was willing to support the US Post Office by passing favorable laws. For example, Congress declared certain roads “post roads” and prohibited private entities from carrying mail on those roads.

However, these private companies were also offering services to carry mail at a much lower cost, which fueled demand for lower postage rates. This competition encouraged the passage of an Act of Congress to reduce and simplify postage rates for letter mail.

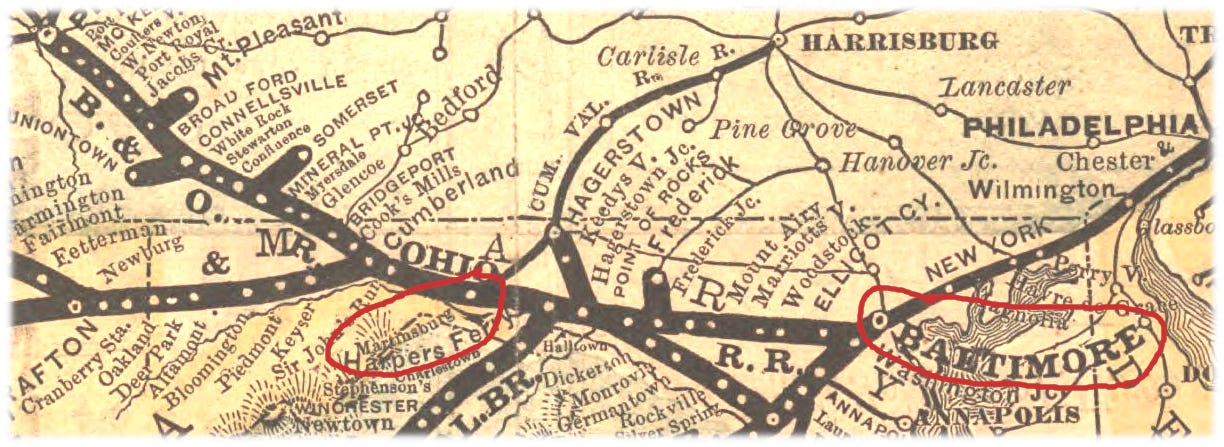

The letter above was mailed April 4, 1849 and the letter contents are datelined from Baltimore with a destination 90 miles away (Martinsburg, Virginia). A big blue "5" shows the postage due (five cents for a letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce and traveling no more than 300 miles). This same letter would have cost 12.5 cents under the old rate structure.

I don’t know about you, but having a cost cut by more than half would be very much appreciated!

The same law that identified post roads also laid claim to the rail lines as post roads. This effectively monopolized the most efficient means of ground transportation at the time. The US Post Office placed mail agents on some of these trains to process mail - typically in a dedicated mail car. We know this letter was processed on the mail car on a Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road train.

Route 1903 was served by a single route agent, James M Watt, between June 4, 1845 and June 20, 1849, thus this route agent stamp was applied by him. If you are interested in learning more about mail car services (including the Baltimore and Ohio), this work by Hugh Feldman might be interesting to you.

The arrival of the postage stamp

The United States issued their first postage stamps in 1847, ushering in a new normal - the prepayment of postage for letter mail. Unsurprisingly, the denominations for these stamps were five and ten cents - matching the simple letter rates for the two distances (up to 300 miles and over 300 miles).

The folded letter shown above includes a dateline of April 24, 1850 from New York City. The red postmark tells us that this letter took the express mail route connecting Boston and New York. That service used a combination of railroad and steamboat to rapidly carry the mail between these major US cities.

The letter was likely placed in a drop box at the pier with the postage prepaid by the stamp. It began its journey to Boston on a New Jersey Steam Navigation Company steamboat. While on that boat, a route agent applied the express mail marking. The steamboat transferred the letter to a railroad at Stonington, Connecticut.

Encouraging pre-payment of postage

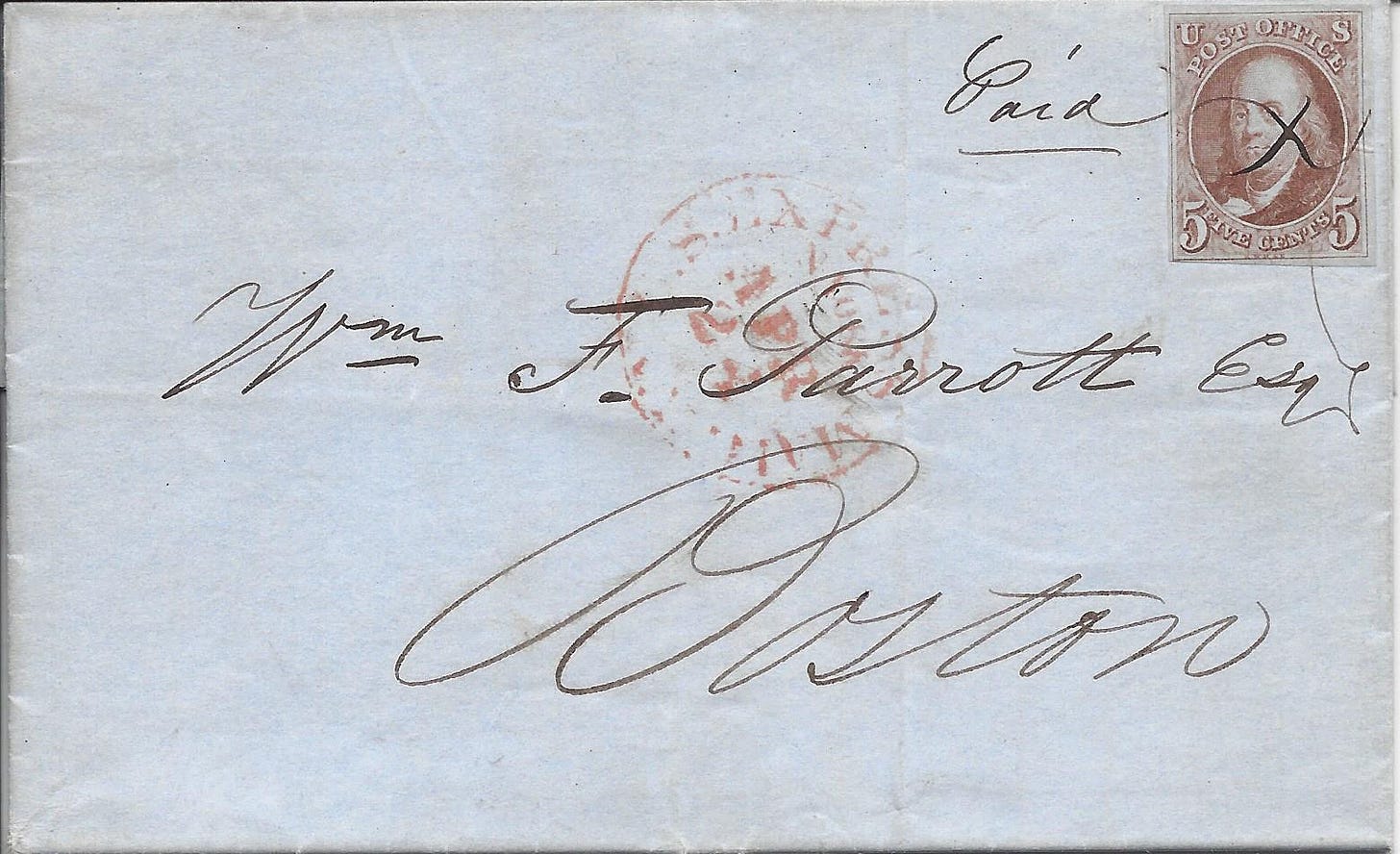

Once we get to 1851, postal service in the United States begins to look a bit more like the system we are familiar with in the present day. The option to send mail unpaid was being phased out and prepayment was encouraged by setting two different rates. If you failed to prepay the postage, it cost you almost twice as much - making a good incentive to prepay.

An Act of Congress issued on March 3, 1851 reduced the letter rate for mail in the United States to 3 cents per 1/2 ounce for items sent no more than 3000 miles (effective on July 1 of that year). A 3 cent postage stamp was issued on July 1, 1851 to show prepayment of this rate. In addition, this act authorized the creation of a 3 cent coin (the first of its type) to provide the public with a convenient method to pay for these stamps.

The simple idea that a coin would be created to facilitate the purchase of stamps to pay for the postage of letters is a compelling story all by itself. This illustrates just how important mail service had become as a primary communication method for a broad section of the populace.

A letter with the new three cent stamp of 1851 is shown below. This folded letter was sent from New Orleans on September 9, 1851 to Providence, Rhode Island. The distance was less than 3000 miles and the weight was no more than one half ounce. In fact, by my measurement, this item is very close to being exactly 1/2 ounce in weight.

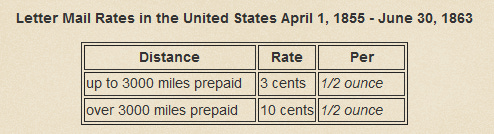

In 1855, things changed yet again! Prepayment was no longer optional and the rates were adjusted once more.

Below is an example of an item that traveled over 3000 miles and required 10 cents in postage per 1/2 ounce.

This letter was mailed in San Francisco on April 3, 1863 and traveled via Panama, arriving at its destination in Boston. This letter must have weighed more than a half ounce and no more than one ounce to require 20 cents in postage, paid by two 10 cent postage stamps.

Postage rates from 1863

To answer the question that was asked about postage rates, here is a table that shows the next several rate periods. Starting in July of 1863, the distance component was removed from the rate calculation for mail inside of the United States. And, if you read last week’s Postal History Sunday, this table might look familiar to you!

The trend for the reduction in postage rates actually continues until 1885. There is a short interruption during World War I when an increase was used to help fund the war effort. Then, once we get to 1932, the trend of increasing rates would slowly begin. The next rate increase would be in 1958 (to 4 cents).

Bonus Material!

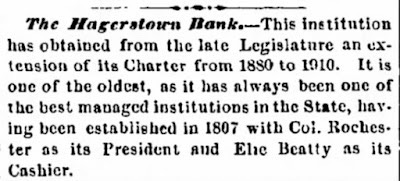

Let me remind you of our first postal history item that I shared at the top of this blog. It just so happens that there are MANY pieces of mail still out in the world for collectors to find that went to Elie Beatty, Cashier for the Hagerstown Bank. It is because of correspondences like this one that postal historians are often able to learn more about how the postal services worked during the time the correspondence was active.

The Hagerstown Bank correspondence has value for historians who study banking systems too. Elie Beatty was a well-respected cashier and was apparently quite talented at his job. The SNAC* site linked in the prior sentence gives us this summary:

"The historical significance of the collection lies primarily in the insights it offers to the operations of a prosperous regional bank during a tumultuous period in United States banking history. The antebellum decades witnessed a series of banking crises, most notably the Panics of 1819 and 1839, recurring recessions and depressions, and the famous "Bank Wars." The financial and political upheaval, combined with disastrous harvests during the 1830s, wreaked havoc on Washington County, Maryland, and caused the Williamsport Bank to suspend specie <ed. precious metal> payments in 1839. Despite the prevailing economic climate, the Hagerstown Bank emerged as a stable financial institution with considerable holdings."

Is it possible that the Washington County Bank in Williamsport is one and the same as the Williamsport Bank referenced in this paragraph? Steve Kennedy, who has studied the Elie Beatty correspondence in some detail, believes that they are one and the same and the SNAC site simply uses the names interchangeably. It’s interesting to note that our letter was sent in 1839, in the middle of the 1839 banking crisis.

Elie Beatty's story can certainly be expanded upon, but I will suggest that you can take the SNAC link and read the summary there if you have interest. If there was a doubt as to Beatty's dedication to his job, I will add the following from the site linked above.

"Beatty resigned his position on April 23, 1859, citing "feeble health and the infirmities of age." Beatty died on May 5, 1859 at the age of eighty-three."

One last tidbit comes from the Hagerstown newspaper:

Elie Beatty served as Cashier for most of his tenure at the bank, but he was president of the bank for just under two years - being pressed into service after the death of the current president of the bank in 1831. While it is clear that Beatty was a highly competent individual, is it possible that he was happier with the hands-on management aspect rather than being the person with the final decision-making power? That may be a question for another time and another person - but it is intriguing nonetheless.

*SNAC (Social Networks and Archival Context)

Thank you for reading Postal History Sunday! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.