Winter has very much arrived and made itself welcome at the Genuine Faux Farm. After a late start, we've had multiple snows, strong winds, and some bitter cold. All in a period of a couple of weeks.

One of the myths that I tell myself about the cold weather is that I'll get to spend more time with the postal history hobby I enjoy. It's a good story, at least, that helps me tolerate trudging out to the laying hens in wind chills of thirty below. But the reality is that there are often more, not fewer trips, out to deal with farm chores. And while I spend less time outside per trip, I probably spend much more time putting on the proper clothing to do the work.

So, this week for Postal History Sunday, I thought I would let myself be carried away some more by carrier covers - all in an effort to forget, if only for a short while, that I have to go collect more eggs before they freeze!

And, before we get into it, it should be noted that the carrier fee to the mails were removed on July 1, 1863. Since I enjoy studying items with postage stamps bearing the 1861 US design (issued in August 1861), you will find most of the covers shown today will be dated between August of 1861 through June of 1863. I'll leave it to other folks to show earlier and later items if they wish!

The letter carrier fee "to the mails"

Just two weeks ago, I focused on carrier letters that showed the one cent fee to pay a US mail carrier to collect the letter from an individual or a letter box and take it to the post office. A small number of the larger cities in the United States provided this service in the 1850s into the 1860s, but their number was increasing as the postal services grew to accommodate the increased volume in mail.

Persons who are interested in this topic can find examples of a US postage stamp paying the one cent carrier fee from larger cities such as Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn and Cleveland. And it should be noted that this fee was for a carrier employed by the US Post Office. There were, at the time, competing private carrier services in some locations as well.

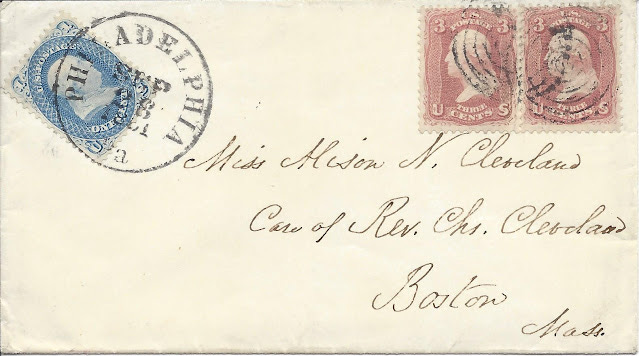

Shown above is an envelope that must have weighed more than 1/2 ounce. The letter rate for a domestic letter within the United States was 3 cents per 1/2 ounce in weight and this letter bears two 3-cent stamps at the top right to pay that postage. On the left is a 1-cent stamp to pay the Philadelphia carrier fee to the mails. That extra penny paid for a US letter carrier to either pick it up from the sender or from one of the post boxes in the city. That carrier would then take it to the post office where it could be prepared to go with the rest of the mail bound for Boston.

This particular item illustrates the difference between a "rate" and a "fee." Letters could be sent at the rate of 3 cents per 1/2 ounce. For an extra fee of one cent, a letter carrier in Philadelphia could bring the letter to the post office for the person wishing to mail the letter. So, even though this letter weighed over 1/2 ounce, the carrier fee did not double like the postage amount did.

Carrier to the mails and delivery in New York City

The small envelope shown above is an example of a letter that was taken to the mails by a letter carrier and carried to the addressee by a letter carrier. We can deduce that it was likely delivered because the address panel includes details for the location of Mary G. Ambler at Number 25 on West 23rd Street. And, in case that was not enough, there is a docket at bottom left that reads "3 doors from V Avenue Hotel," which is likely referencing the very new Fifth Avenue Hotel that had recently been completed 1859). A letter that was going to be held at the post office for the recipient to pick up typically would not include a detailed location.

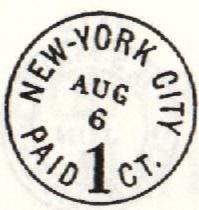

This letter took advantage of the one-cent carrier fee that paid for pick up and delivery of letter mail within New York City. We can determine this is the case both because there is a one-cent stamp paying the postage and there is a postal marking that is known to indicate this carrier service at the time. A tracing of this marking (with a different date) is shown below:

Now, before I go much further, I want to point out that a cover with a one-cent stamp alone does not necessarily indicate carrier services. It's the combination of the one-cent stamp with this particular marking that confirms it for us. However, there are other situations that might call for a single one-cent stamp on a cover.

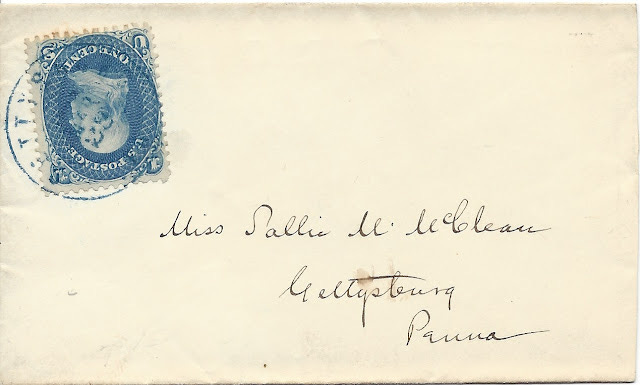

The small letter shown above is good example. The postmark on the stamp is for Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and the letter is addressed to the same location. Gettysburg did not have a US postal carrier at the time, so there is no way this paid for those services. On the other hand, there was a one-cent rate for letters dropped at the post office that were also intended to be picked up at the post office - just as this one was.

So, the take-away here is that we also need to know that the post office in a given town or city actually employed letter carriers before we can consider the possibility of a carrier fee on a cover.

Some were destined to leave the United States

The one-cent fee for carriage to the mails was independent of the postage rate, as we saw with our first example. But, let's drive that point home a bit further.

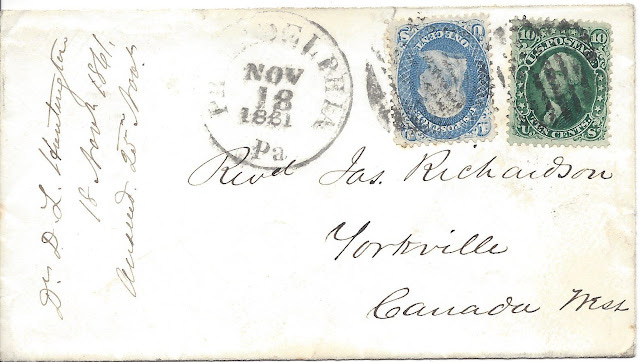

Shown above is a letter mailed in Philadelphia and destined to Canada. The postage rate for a simple letter from the US to Canada was ten cents at the time. And, sure enough, there is a green ten-cent postage stamp at the right paying the cost for that rate.

This is the part where you say, "Hey! There's a one-cent stamp on there too. Philadelphia had letter carriers. I bet this is an example of carrier service to the mails too!" And the good news is, you would be correct. Good job!

An extra penny of postage paid beyond the required postage rate, in addition to the knowledge that there were carriers picking up mail in a given city, makes a strong case for the carrier fee.

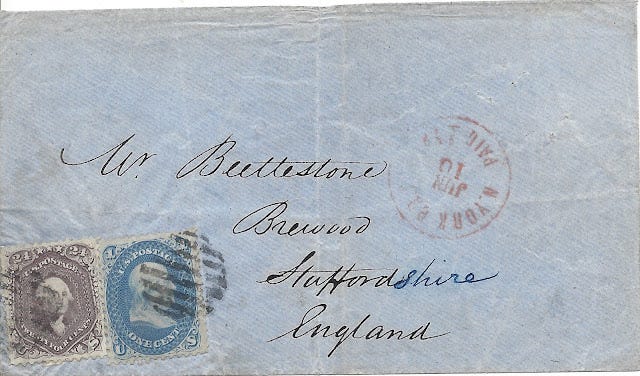

Here's another good candidate. This letter was mailed from New York City to Staffordshire, England. The postage rate for a simple letter from the US to the UK at the time was 24 cents for a letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce. The 24-cent stamp at the left pays that postage rate, and the 1-cent stamp at the right paid for the carrier service in New York City to the mails.

The case is made stronger by the fact that an additional stamp (the 1 cent stamp) was added to this cover in addition to the amount required for the letter postage rate. Why would a person bother to separate another stamp from the sheet, lick the back, and then stick it on the envelope unless they intended for it to pay for some sort of service?

The answer is: they wouldn't. So, it is pretty clear the extra penny was intended to pay for the carrier service to the mails.

Here is an example that I hope will illustrate what I mean. The total postage on this cover is 30 cents. The postage rate required for this item was 28 cents. The stamps on the cover include one 24-cent stamp and two 3-cent stamps. What were the extra two cents intended to pay? Or did they pay for anything at all?

The item was mailed in New York City, so there were letter carriers available. So, it is possible this was an attempt to pay carrier services. But, I don't make the claim that this happened. Why?

First, the old rate to Brunswick was 30 cents per 1/2 ounce and it had recently (within a few years) been changed. Also, the rate for letters that were sent unpaid was 30 cents and 28 cents when it was properly paid. So, it is entirely possible (in fact, likely) that this was a simple mistake in identifying the postage rate. It is also possible that this was a "convenience overpay." The person had 3-cent stamps and 24-cent stamps, which didn't provide a good option to get to 28 total cents. So, they just got as close to the total they could with what they had.

This would be different if there were 29 cents of postage on this cover and one of the stamps was a one cent stamp. It certainly would NOT be a convenience overpay - what's convenient about adding another stamp? And, it would clearly not be due to rate confusion - unless they thought they would take the average of the two and give that a go!

The final piece of evidence is that this letter was mailed in 1865, well after the July 1, 1863 date where the carrier fee was removed. Since there was no carrier fee, it couldn't have been used to pay it. But, even if this had been mailed in 1862, I would not make the claim that it was an attempt to pay for carrier service.

That brings us back to another cover that traveled from New York City to England. This one was mailed in early 1863. Once again, a 24-cent stamp pays the postage rate and a 1-cent stamp pays the carrier fee to the mails. Letter carriers did work in New York City. The date is prior to July 1, 1863. And, there really isn't any other reason for a person to add a 1-cent stamp to this particular cover other than to pay that carrier fee.

While it is certainly not at all difficult to find covers that illustrate the combination of a carrier fee with the domestic letter rate (3 cents), it is much harder to find examples that traveled to destinations outside of the United States. They certainly exist, most frequently to Canada. I have also seen examples with payment for carrier service to the United Kingdom, France and Italy. There aren't lots of them, but there are enough to confirm that it did happen and to establish patterns so we can more readily identify them.

More competition for the US Post Office

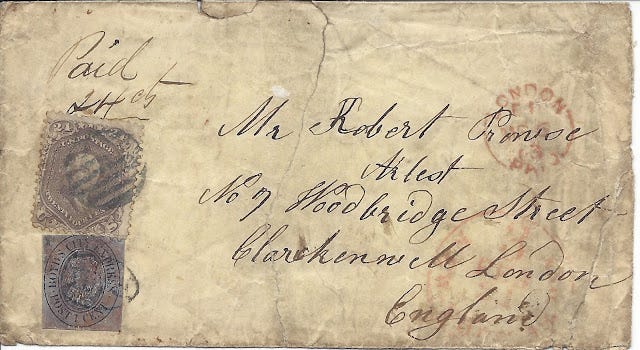

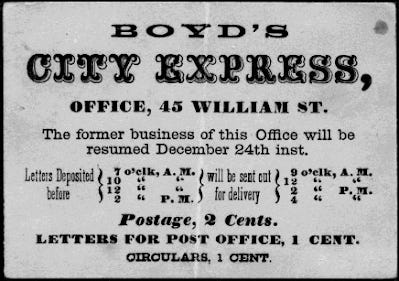

In the Postal History Sunday from two weeks ago, I showed an example of a Blood's Penny Post item where a private carrier picked up the letter and brought it to the post office - instead of a letter carrier employed by the US Post Office. This week, I am showing an example that was carried by Boyd's City Express (New York City) to the mails.

Like the Philadelphia Boyd's cover, this battered envelope shows a 24-cent stamp that paid the US postage for the rate to the United Kingdom. It also has a Boyd's City Express stamp that indicates the 1 cent fee they required to carry the letter to the post office had been paid.

Like Blood's Penny Post, Boyd's City Express opted to ignore the decision that only the US Post Office could carry mail on designated post roads. Unlike Blood's, who closed in 1862, Boyd's continued to provide their services for local mail delivery until 1883, when government officials raided the business offices. While fines were levied against them, they remained open for business to carry mail for a couple more years before terminating that service. However, they changed their business priorities to focus on mailing lists and address labels.

Some of you might have noticed that someone wrote "Paid 24 cts" just above the 24-cent stamp. In fact, if you look closely, you can see that the stamp is actually placed over the writing. This tells me that it is likely the letter was handed to a Boyd's letter carrier along with payment for the 24 cents in postage. Since neither the Boyd's carrier, nor the person sending the letter had a 24-cent stamp, they simply wrote the payment amount on the envelope. Once the letter carrier got to the post office, they passed on the payment that led to the addition of the postage stamp.

Like Blood's Penny Post in Philadelphia and the US Postal Office in New York City (and other carrier cities), Boyd's maintained boxes where customers could drop letters for pick up by persons employed as letter carriers by the City Express. The National Postal Museum includes a description and a photo of one of the two remaining post boxes known to still be in existence today.

Now, I will grant you that this Boyd's cover is not pretty - lacking a bit in curb appeal. But, I have yet to find any other example of this combination of Boyd's carrier service to the mail that then goes to the United Kingdom with 24-cents paid by an 1861 series postage stamp. In other words, as far as I know, it's the prettiest one out there. That's plenty of curb appeal for me.

Bonus Material

The "V (Fifth) Avenue Hotel" referenced by the docket on our second cover, was located between 23rd and 24th Streets on the southwest corner of Madison Square in Manhatten (NYC) from 1859 to 1908. Construction was underway in 1856 and reached completion in 1859 at cost around two million dollars.

During construction, the Fifth Avenue Hotel was dubbed "Eno's Folly" after Amos Eno, the developer responsible for its construction. Detractors felt that it was too far away from the established city center and would fail to attract patrons. However, it rapidly attracted the attention of those with power and money, becoming both a cultural and political gathering point for the elite class.

Our second letter was received at a pivotal point for the neighborhood. The construction and success of the Fifth Avenue Hotel led to further development around Madison Square Park. Still, in the early 1860s, this hotel was new and it clearly stood out - making it an excellent landmark to use if you wanted to tell a letter carrier you were just three doors away.

Want to learn more?

There are numerous excellent resources available to those who might like to learn more about carrier covers. The topic is well-studied and much broader than I could possibly cover in a couple of blog posts. Here are a few suggestions for those who might like to explore a bit more:

The Carriers and Locals Society promotes the study of private carriers and local posts in the United States. Their site includes articles and exhibits that might be of use.

A short article that methodically summarizes the history of carrier fees and drop letter rates in New York City can be found in the US Philatelic Classics Society Chronicle if you would like to see a broader context of this topic.

Thank you for joining me this week. I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Additional Reading

I have heard from some people that one Postal History Sunday isn’t enough on some weekends. So, here are links to other PHS that are related to today’s topic.

Carried Away - PHS #177

The Rural Burden - PHS #74

Independent Mail - PHS #21

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. Some Postal History Sunday publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.