Childhood Dreams

Postal History #222

Here we are, at the seventh day of the week (or the first depending on when you start your week). If you are reading this, I suspect you have some idea as to what you are getting into.

It is often our tradition - as part of the opening to a Postal History Sunday - that we find a creative way to push our troubles and our worries aside for at least a little while so we can all enjoy something postal history related. The idea is that if we do that, we might all learn something new and perhaps find a positive to balance out the weight those troubles and worries add to our lives.

Today's plan? Put those troubles onto that key ring that most people have. You know the one! The key ring where you put the keys you will rarely, if ever, use. In my case, the key ring actually has several keys I can’t remember what the belong to. But, I’m not going to throw those keys just in case they are important. Perhaps you’ll also forget what those troubles were for too!

Surface Mail

Like many philatelists or postal historians, I started in the hobby when I was quite young. I can still recall clearly my perceptions of the hobby, including the feeling that most of the things that I knew existed would always be unattainable. Always a dream, never a reality.

There was one dream that I think I realized would be attainable someday - completing the 1934 US National Parks stamp issue. But, of course, someday always seemed so far away. But that day did come. And now I enjoy finding postal history that uses these postage stamps.

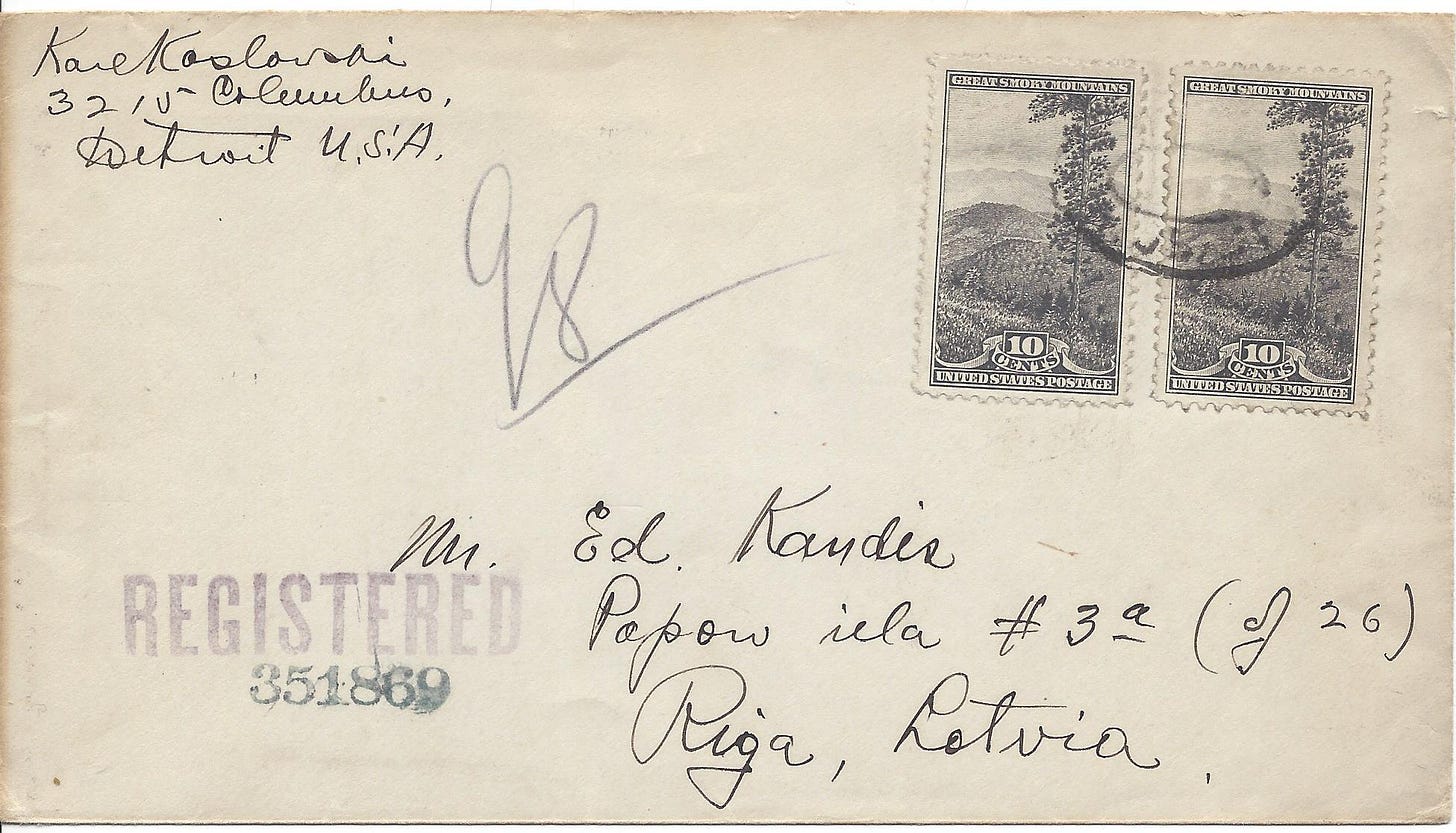

Shown above is a letter mailed from Detroit, Michigan, to Riga, Latvia, in September of 1935. This was sent as a registered letter via surface mail to a foreign country and two 10-cent stamps from the National Parks issue were used to pay for the postage and the registered mail fee. And, just in case you were wondering, the ten-cent stamp was one of those “maybe someday” stamps in the series I hoped to get.

I just noticed that one of you has your hand up in the back! And you’ve got a good question that deserves an answer.

What is surface mail? Surface mail’s counterpart would be air mail, which was beginning to get a strong foothold in the 1930s. Surface mail was less expensive and could use various modes of transportation via ground and water to get to where it was going. Postal historians don’t use this term much until we start to discuss the era where air mail becomes more common. Prior to the 1920s and 30s, there were rare exceptions, but nearly all mail traveled via surface mail. So, there is no reason to make the distinction.

In the case of the letter above, it likely took a train to a port city, such as New York or Boston, and boarded a ship to Europe. By the time we get to 1935 there were many options for mail to be carried over the Atlantic and the lack of markings do nothing to help us figure out the route this might have taken.

In 1934, this series of ten stamps were issued to honor the National Parks of the United States. Each of the ten stamps had a different denomination, from 1 cent (Yosemite) to 10 cents (Great Smokey Mountains). The stamps on this cover were the denomination that was issued last (put on sale October 8, 1934). If you have interest in reading more about the background of this issue, there is an article with large pictures of each denomination offered by the White House Historical Association.

This series of stamps caught my attention early in my collecting endeavors. As a kid, with a kid's budget, I was pretty much able to acquire things with minimum value, often given to me by relatives. The National Parks issue of 1934 had a few values that fell under that category, but the 10 cent Great Smokey Mountains stamp was not one of those. If I recall correctly, it had a catalog value in the neighborhood of $1.70, which was a relative fortune.

I think we all have things that trigger early memories and many of us are fortunate to have pleasant memories we don't mind recalling. This stamp issue does that for me. And, the ten-cent value has a personal significance because it was the first stamp I targeted to save up for as a very young collector. So, when I came across this particular item from Detroit to Riga more recently, I did not have to think too hard about adding it to my personal collection.

Foreign Letter Mail

Many of the envelopes and mail pieces that feature 1934 National Parks issue stamps are what I would identify as souvenir items or philatelic covers. In other words, they were placed on a cover to commemorate a particular event (many to commemorate National Parks events - of course) or to feature the first day of issue for the stamp (First Day Covers or FDCs). The focus of the cover was to create a keepsake rather than to carry something through the mail.

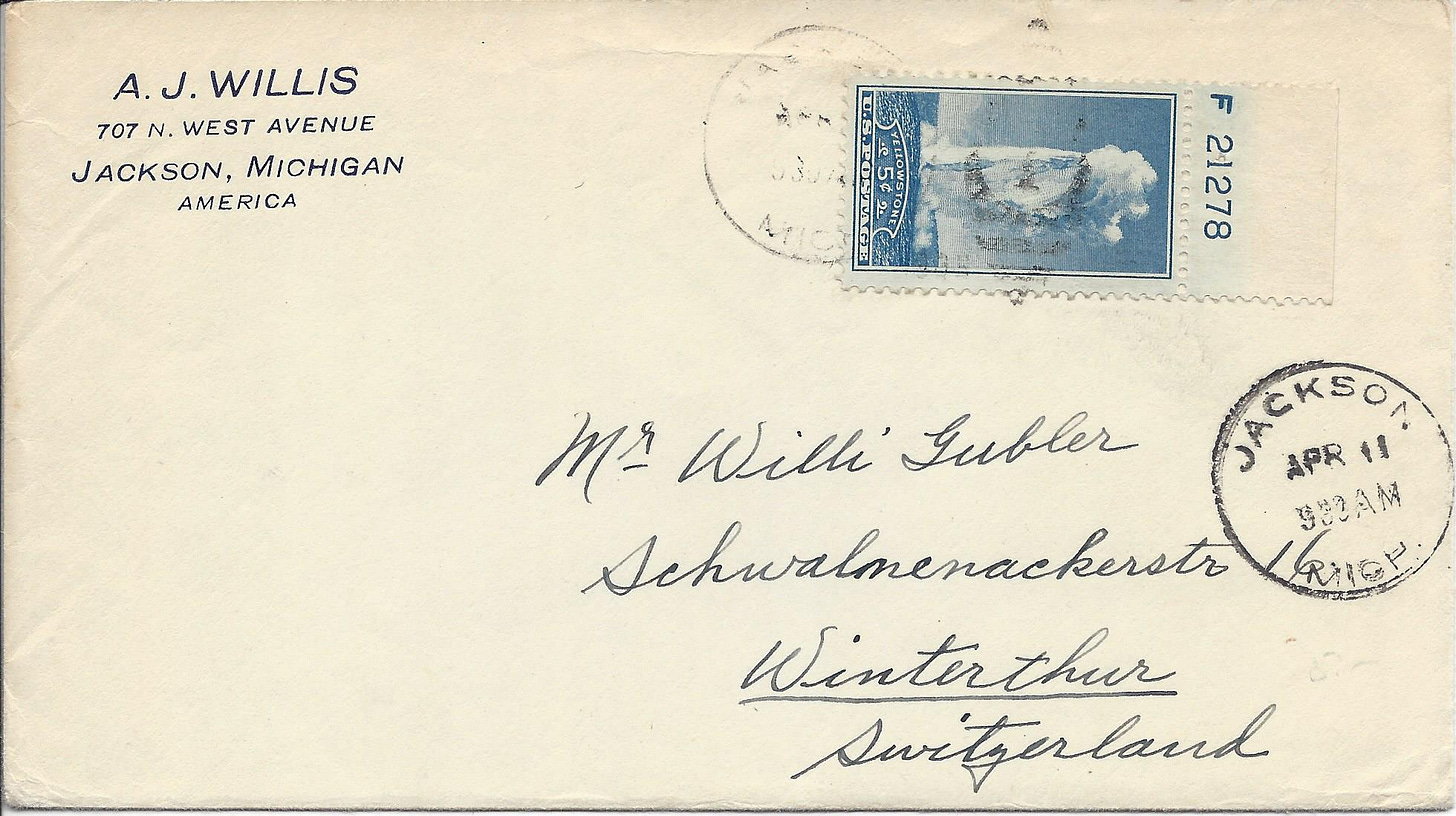

I prefer to collect and learn about items that had the postage paid by these stamps with the purpose to carry the contents in the mail. In addition to my desire to find examples of regular letter mail using these stamps, I prefer items that went to another country other than the United States, such as the item shown above that was sent to Winterthur, Switzerland, from Jackson, Michigan.

The United States was among those countries that joined the General Postal Union at its inception. The letter rate for surface mail to other participating nations was set at 5 cents per 15 grams on July 1, 1875. The General Postal Union became the Universal Postal Union, and the UPU continued to refine the postal agreement, resulting in some changes in those rates. As of October 1, 1907, the cost was now 5 cents for a letter weighing no more than 20 grams.

An item that qualifies for the first weight level for a postal rate is often referred to as a "simple letter." The rate for a simple letter would not change again until November 1, 1953.

The letter shown above was postmarked in 1935, so it must have qualified as a simple letter.

You might notice that the postage stamp, featuring Old Faithful at Yellowstone, includes a bit of the selvage (the border around a sheet of stamps) and the printing plate number. This tells me that it is likely that either the sender or the recipient (or both) were interested in or had some knowledge of philately (stamp collecting). There are collectors who collect items that include the selvage with a plate number intact

That, in and of itself, does not make this a philatelic cover because it does properly pay the rate and there are no further markings that attempt to turn the cover into a souvenir item. But, it is fairly safe to say that most uses of this series were probably the result of a person being aware of someone who collected stamps.

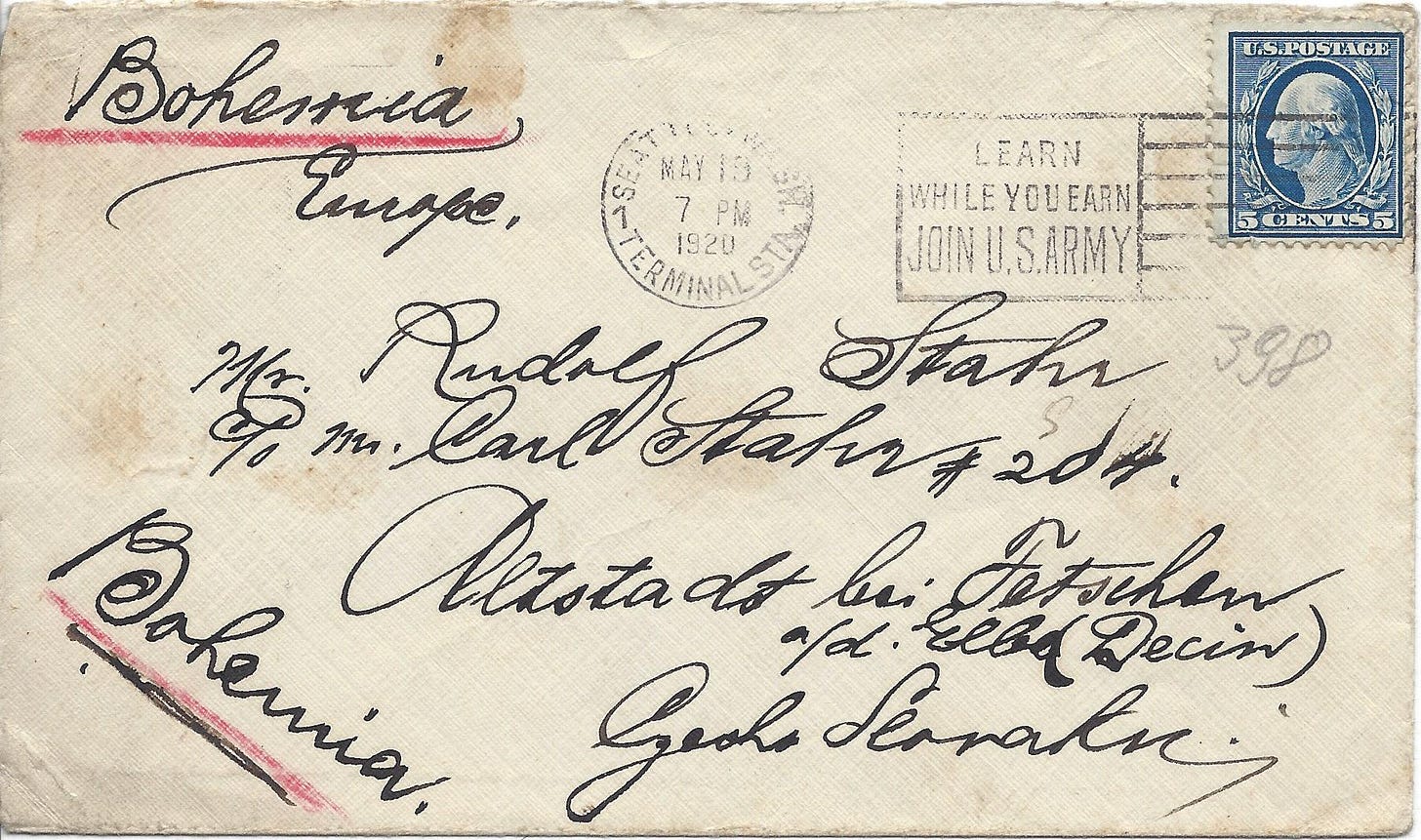

The general public would be more likely to use postage stamps that might look more like this one.

The National Parks issues are classified as commemorative stamps. Their counterpart would be definitives, just like the 5 cent Washington stamp shown above. Definitive stamps were often issued as a series with multiple denominations and a single design that was typically maintained for many years. Commemoratives, on the other hand were printed over a much shorter period of time and, frankly, were intended to attract stamp collectors - especially those who wanted to keep copies of each design without using them on mail.

How Heavier Letters Were Handled

Another interesting feature about the new surface mail postage rates to foreign countries in 1907 was that the amount for each additional unit of weight after the first was actually LESS than the first unit of weight. Prior to this point, the cost was 5 cents for every 20 grams in weight.

As of the 1907 rate change, an item weighing no more than 20 grams (a simple letter) would still cost five cents. But, each additional 20 grams of weight only added 3 more cents to the postage.

This piece of letter mail sent from Woonsocket, Rhode Island, to Yonne, France, must have weighed more than 20 grams, but no more than 40 grams. The cost? Five cents for the first 20 grams and three more cents for the next 20 grams for eight cents in total. This postage was paid by four of the 2 cent stamps from the National Parks issue.

The two-cent National Parks issue features the Grand Canyon. Once again, I would not be surprised if the sender or receiver was a stamp collector. There is selvage at the bottom of the stamps that was not removed. And, the choice of a block of four 2-cent stamps to a person that is likely related to you implies (at least to me) that the individual was hopeful the envelope would come back to them at some point in the future after it had done its job carrying a letter overseas. Or perhaps, the selection of stamps was because the recipient was known to collect. Either way, the letter carried mail properly and the envelope does not carry additional adornments, so it interests me as a postal artifact.

Please note, I am not denigrating anyone who enjoys collecting philatelically inspired postal items such as FDCs or event covers. There is plenty in that area to explore and enjoy. The difference is merely that they don't interest me as much as the items in this post do. We all have to set our boundaries and priorities. The good news is - it’s all our choice!

Registered Mail

Persons who wanted to send items of value in letter mail had the option of using Registered Mail to pay for additional tracking by postal agencies as the item traveled through the various mail services. The first such rate established by the Universal Postal Union was 10 cents on April 1, 1879. This was increased to 15 cents on December 1, 1925, which is where it stayed until 1945 (it then increased to 20 cents).

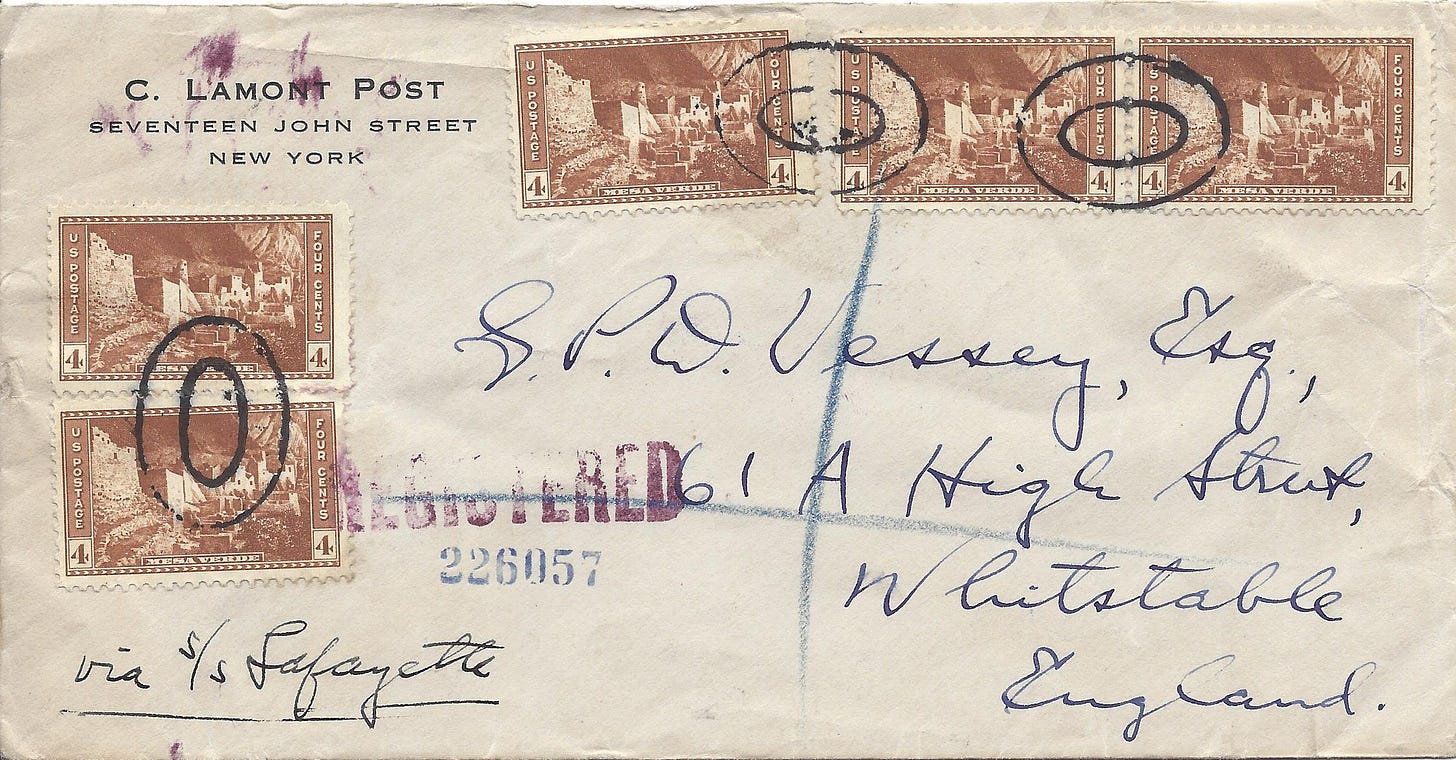

The letter shown above was mailed in 1936 from New York City to Whitstable, England. Five copies of the four-cent stamp were used to pay a total of 20 cents in postage (just like the first cover I shared in this post). These stamps paid five cents for the price of a simple letter using surface mail because the letter weighed no more than 20 grams. Fifteen cents were charged for the Registered Mail services.

As a side note, the registration fee did not change based on the weight of the item, even while the letter weight did. So, if the previous letter had been registered, it would have required 8 cents for letter mail postage and 15 cents for registration (23 cents total).

If you look at the center left of the cover shown above, there is a purple handstamp that says "REGISTERED" and a registry number is placed just below that marking (226057). In addition to those markings, a blue cross was placed on the front to give mail handlers another visual clue that this item was to be given registered mail services. This cross is prevalent in mail that was carried at some point by the British mails, but it is not necessarily seen on US mail items (unless going to the UK) - so we might be able to conclude it was added by a clerk in the British mail system.

The same can be said for the blue marking on the back of the cover shown below. Yes, that is also supposed to be a "cross," but I think the clerk had more than one of these to process and wasn't feeling particularly interested in precision at that moment.

Since registered mail often carried items of value, registry postal markings were often placed over the area where the flap adheres to the rest of the envelope. The idea was that if someone tried to open the envelope it would be apparent by the disturbance of those markings. This is akin to the old wax seals that were applied in earlier mail. Of course, this letter was not opened by tearing open the flap. Instead, an end of the envelope was slit with a knife or letter opener - so this security feature was a bit of a moot point in that regard.

The four-cent stamp features Mesa Verde in Colorado.

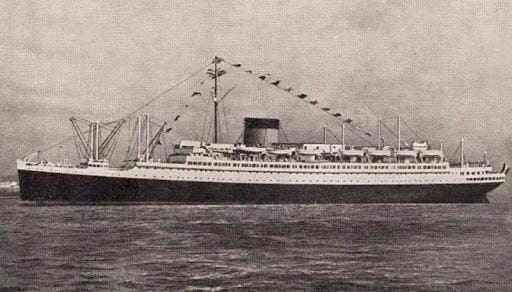

This cover adds a level of interest with the docket that reads "via S/S Lafayette" at the lower left side of the envelope. The Lafayette was the first diesel powered ship in the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique's (CGT) fleet.

Lafayette was placed into service in 1929 or 1930. I am not certain which is correct as the Great Ocean Liner site is unclear as to which year that would be. Other sites make a distinction for the launch date (1929) and the maiden voyage (1930), which may be correct. If someone else feels that they want to know more and they figure it out, feel free to share with me and I can add it in.

The typical sailing routes for CGT were to leave New York, stop in Plymouth or Southampton in the UK and then terminate the sailing at Le Havre in France. So, it makes sense that mail destined for the British islands would offload at either Plymouth or Southampton rather than continuing on to France. Unlike mail in the 1860s, there are no exchange markings for the arrival of the mail, so we have to find evidence in the newspapers for the arrival of the Lafayette in either Plymouth or Southampton to figure out how this letter got to the United Kingdom.

The New York Times reports that mails for Europe via the Lafayette had to be received at the post office by 8 am on April 18 for the ships departure on that day. Another ship, the American Trader, left New York on the 17th, but its mails closed at noon. So, we can guess the letter writer got the letter to the post office after that point in the day on the 17th.

And, sure enough, we have an arrival at Plymouth on April 26 for the Lafayette as reported in the London Daily Telegraph. It would not be a surprise if this registered letter were delivered on the 26th or 27th to the addressed in Whitstable.

The Demise of the Lafayette

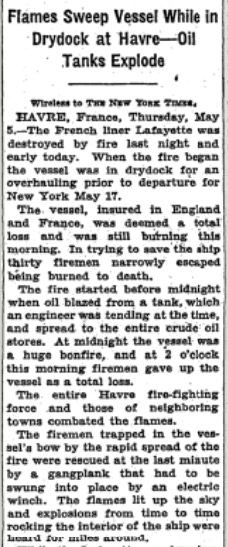

The Great Ocean Liner site referenced above gives a more complete story of the diesel-powered Lafayette. Or, if you want a more contemporary account, the article in the New York Times on May 5, 1938 includes its construction history. The Lafayette met its demise on May 4 of 1938 while it was receiving repairs in drydock at Le Havre, France.

The loss of the steamship rated first page news for the New York Times. Crude oil tanks caught fire after an engineer tried to light an oil burner around 9:15 PM. Apparently, oil that had been spilled on the deck was also ignited and it was not long before much of the ship was in flames. The crew barely escaped by using lines thrown to them from the dock.

Fire crews from Havre and surrounding towns arrived at the scene, but they gave up fighting the blaze on the ship by 2 AM. Several firemen had a narrow escape and from that point on they only worked to prevent the fire from spreading further. Explosions from the ship could be heard for “miles around” and continued until about 4 AM.

It wasn’t until three weeks later that it was discovered that not everyone had been able to escape the flames.

Air Mail

Since I took the time to describe surface mail, it makes sense to show you something that used air mail!

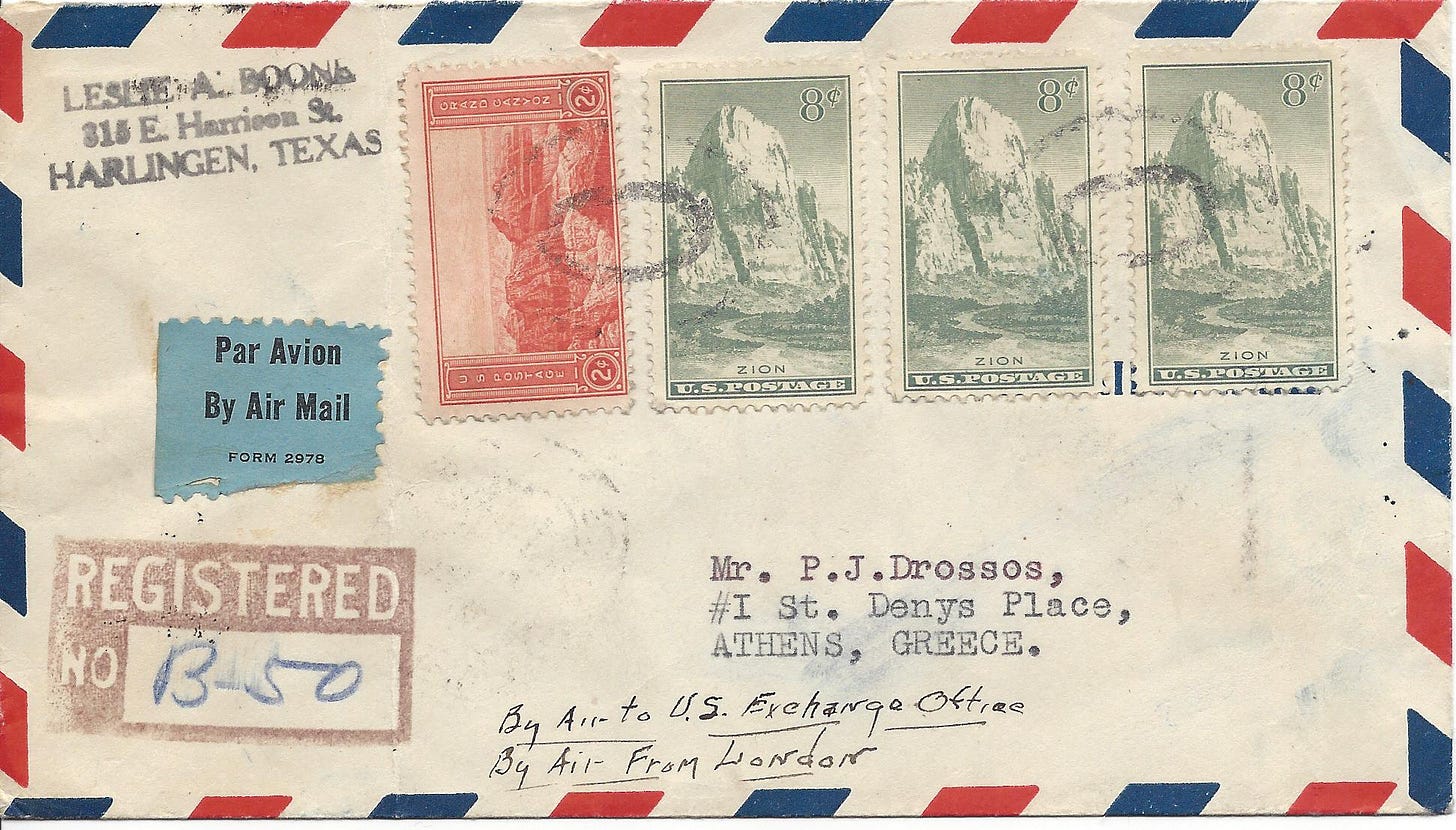

Here is a letter that actually used the air service in the United States, crossed the Atlantic on a steamship, and then used air mail in Europe to get to Athens, Greece in 1935. The cover itself gives me multiple confirmations that my reading of its travel is correct. A blue label (Par Avion / By Air Mail) states that air mail is to be used. Red and blue parallelograms around the edge also indicated to the post office that air services were desired.

We also have this docket at the bottom of the envelope that may have been a directive to simply confirm what the postage was for. It is also possible this text was added AFTER the letter had gone through the postal services by a collector. I have no sure way of telling, but air mail was new enough that some direction in the form of a docket might have been useful.

The postage costs for air mail went through a number of changes in the early years and some of the calculations could get a bit complex. Happily, this one is not so difficult. We can start with the fifteen cent fee for a registered letter. That leaves us with 11 cents for the letter mail postage.

The US required 8 cents in postage for each ounce in weight (Nov 23, 1934 - Jun 20, 1938), which included postage for the air carriage to the Atlantic port city as well as the Atlantic crossing on a steamship to England. An additional 3 cents was added for each half ounce for air carriage in Europe (Jul 1, 1932 - Apr 27, 1939).

Well, I sure am glad that adds up properly (15 + 8 +3 = 26 cents)!

Additional Resources

The Smithsonian's National Postal Museum created a series of media items under the title Trailblazing: 100 Years of Our National Parks. These media items highlight things shown in their 2016 exhibit on this topic.

The National Postal Museum also provides large photos and decent descriptions of postage stamps issued by the United States. This link will take you to the National Parks issue descriptions and photos.

This thread on the Stamp Community discussion board features one collector's focus on stamp essays and First Day Covers. There isn't much on postal history there, but it is still a fine example of how collectors often share their knowledge with other collectors.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I think you have used Tony W's book when describing the rates for registered mail. But he missed one rate change which was later published in his errata on Stampsmarter; The registration fee was reduced to 8c on 1 Jan. 1893 and increased again to 10c on 1 Nov 1909.