There is one question that I get asked frequently. Sometimes I am the one doing the asking - but usually it is presented to me in various ways from a wide range of individuals who encounter Postal History Sunday.

Why?

Why publish a weekly article? Why are you doing this Postal History Sunday thing?

The quick and dirty answer is that I enjoy facilitating learning and I feel an obligation to use my talent for building bridges toward understanding and knowledge.

And I fully acknowledge that this answer comes up short. Maybe I’ll answer that better if some of you ask for more.

So, in honor of coming up short, I thought we could look at examples of letters where the postage paid came up short. I thought it would be interesting to consider the different reasons a letter would have been only partially prepaid during the 1850s and 60s time frame.

So, grab a beverage of your choice and put on your fuzzy slippers. Settle into that comfy reading space and let’s dive into this week’s Postal History Sunday!

1. Too much in the envelope

Our first two examples follow a similar theme. Sometimes people put too much in the wrapper and the weight was enough to require more postage.

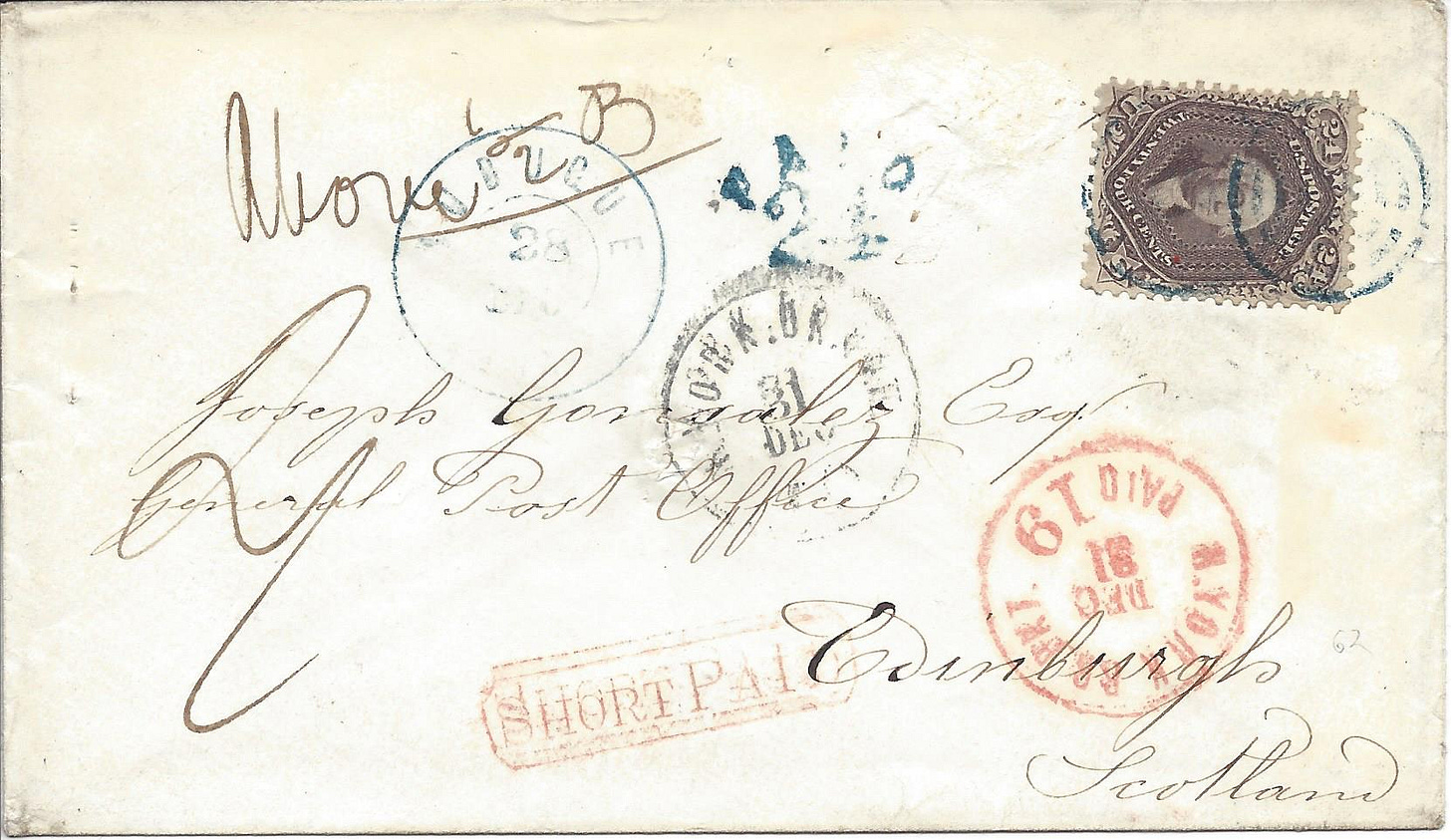

The envelope shown above was mailed on December 28, 1863 in Dubuque, Iowa. The intended destination was Edinburgh, Scotland and the postage required for a simple letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce was 24 cents. The letter bears a 24 cent stamp AND the Dubuque post office used a handstamp to indicate that the 24 cents were paid.

Apparently, from the point of view of the Dubuque postal clerk, this letter did not weigh too much and the postage was correct. So, they did not ask for anything more from the sender and shipped it to the New York Foreign Mail Exchange Office.

The Foreign Mail Clerk in New York made the intial assumption that the Dubuque post office knew what they were doing and put on this handstamp indicating the letter was fully paid. The letter was destined to go on a trans-Atlantic ship under contract with the British, so 19 of the 24 cents were to be passed to the British Post Office, while the US kept 5 cents for their expenses getting the letter from Iowa to the ship in the New York Harbor.

After putting the paid marking on the envelope, I suspect the clerk was about to put the letter into the mailbag when they recognized the letter felt a little bit heavier than usual.

Now, if you don’t believe a person who works with a lot of letters would be able to recognize when a letter is over 1/2 ounce, I’ll vouch for them. I have bagged hundreds, if not thousands of bags of green beans at 1 pound each. After the first few hundred bags, a scale became optional. I could apply this to other produce as well. In fact, it used to be a bit of a “carnival stunt” for me to guess the weight of people’s tomatoes at farmers’ market before actually putting them on the scale.

I was correct well over 90% of the time.

In any event, this clerk verified the weight by placing it on a scale and found that the letter DID weigh more than 1/2 ounce. Now they had to correct the messaging that was to be sent on with this letter and they wrote “Above 1/2 Oz” on the envelope.

Then, they found the handstamp that reads “Short Paid,” and marked the envelope so the receiving Edinburgh post office would understand that the letter was not properly prepaid. They also put a black New York exchange marking on the envelope. A black exchange marking was code for “this letter is not properly prepaid” and clerks in the exchange offices knew this (red indicated the letter was paid in full).

Technically, they probably should have struck the “short paid” marking in black ink as well. But, they could get away with being a bit more sloppy because the destination country also spoke/read English. If this letter had been destined to, perhaps, France or Italy, it might have been more critical to get everything exactly correct.

The postal clerk in Edinburgh understood that the letter was not properly paid based on these markings. They also knew that short paid letters were to be treated as if NOTHING had been paid in postage. So they placed a due amount of 2 shillings - equivalent to 48 cents in the US - on the front of this letter.

Now, when Joseph Gonsall came to the post office in Edinburgh, the clerk would know to collect 2 shillings before handing over the letter. I hope the letter had good news, because it cost a lot more (a total of 72 cents or 3 shillings paid) than it would have if the sender (and the Dubuque post office) had gotten it right the first time around.

2. Different weight units could confuse things

There are two hurdles that frequently get in the way when a person tries to understand postal history between countries. The most obvious difficulty has to do with the differing language and currencies. But as we dig a little deeper into postal history, the non-equivalent units of measurement can be quite a challenge.

Well, it turns out that differing units for measuring weight isn’t just a challenge for those of us trying to puzzle out a cover and how the postage was calculated. It had the potential to cause its fair share of problems in the 1800s as well!

The folded letter shown above was mailed on August 23, 1866 from Bordeaux, France to Jerez de la Frontera (near Cadiz), Spain. The sender paid the postage for a single weight letter with a 40 centime stamp, but the letter was too heavy and required more postage. So, on the face of it, it isn’t terribly different from our first item.

However, is it possible that the reason this letter was overweight was because France and Spain used different weight units? Before I go much further, the answer is actually “no,” but there certainly could be some confusion and oddities could possibly occur.

The postal convention between these two countries was put into effect on February 1, 1860. To make matters simple for explanation in a blog post, the basics were as follows:

Prepaid Letters Postage:

France ----> Spain = 40 centimes per 7.5 grams

Spain -----> France = 12 cuartos per 4 adarmes (about 7 grams)

Do you see a possible problem? I sure do! Technically, an item that weighed 7.2 grams would be light enough for a single rate in France, but it would require a double rate in Spain. Clearly a recipe for potential problems.

Apparently, the French post office was aware that this item weighed too much, so they put the red boxed marking on the cover which reads "Affranchissement Insuffisant" (insufficient postage). This marking is similar to the “Short Paid” marking the New York exchange office clerk used on our first cover.

Since it was the French that identified the underpayment, we know it must have weighed more than 7.5 grams. If the Spanish had indicated an underpayment, we would be right to wonder if they were penalizing a letter that fell into that “gray area” between 4 adarmes (7 grams) and 7.5 grams.

I believe it was the French traveling post office on the train to Irun (Spain) that calculated the amount due and put the big red "24" on the front of the cover. And it is the calculation of postage due where things get really interesting.

The postal convention allowed people to send letters paid or unpaid. I’ve already shared the postage rates for prepaid postage. Now it’s time to share the rates for letters that were sent unpaid:

Unpaid Letters Postage:

France ----> Spain = 18 cuartos per 4 adarmes

We actually have to know this postage rate to calculate the amount due for this letter.

So, how was the amount due calculated?

This letter weighed more than 7.5 grams and no more than 14 grams*, so it is a double weight letter.

Because the letter was short paid, the unpaid letter rate was used to calculate postage due. 18 cuartos x 2 = 36 cuartos.

The amount prepaid in France was 40 centimes which was equal to 12 cuartos. We deduct the amount paid from the amount due. 36 cuartos - 12 cuartos = 24 cuartos

And there you have it. Underpaid mail was penalized for failure to prepay the service properly by charging the unpaid mail rate to calculate the total fee due. However, unlike many other mail agreements of the time, this one actually gave some credit for the attempt to prepay the postage. But, if you think about it a little harder, you will realize the recipient actually paid as MUCH as the sender would have paid if they had calculated the amount due correctly in the first place.

*For those of you who might be thinking 14 grams is a typo, remember that the postage due rates were calculated in adarmes. So a double rate is more than 4 adarmes (7 grams) up to 8 adarmes (14 grams).

3. Postal rate mistakes and misunderstandings happen

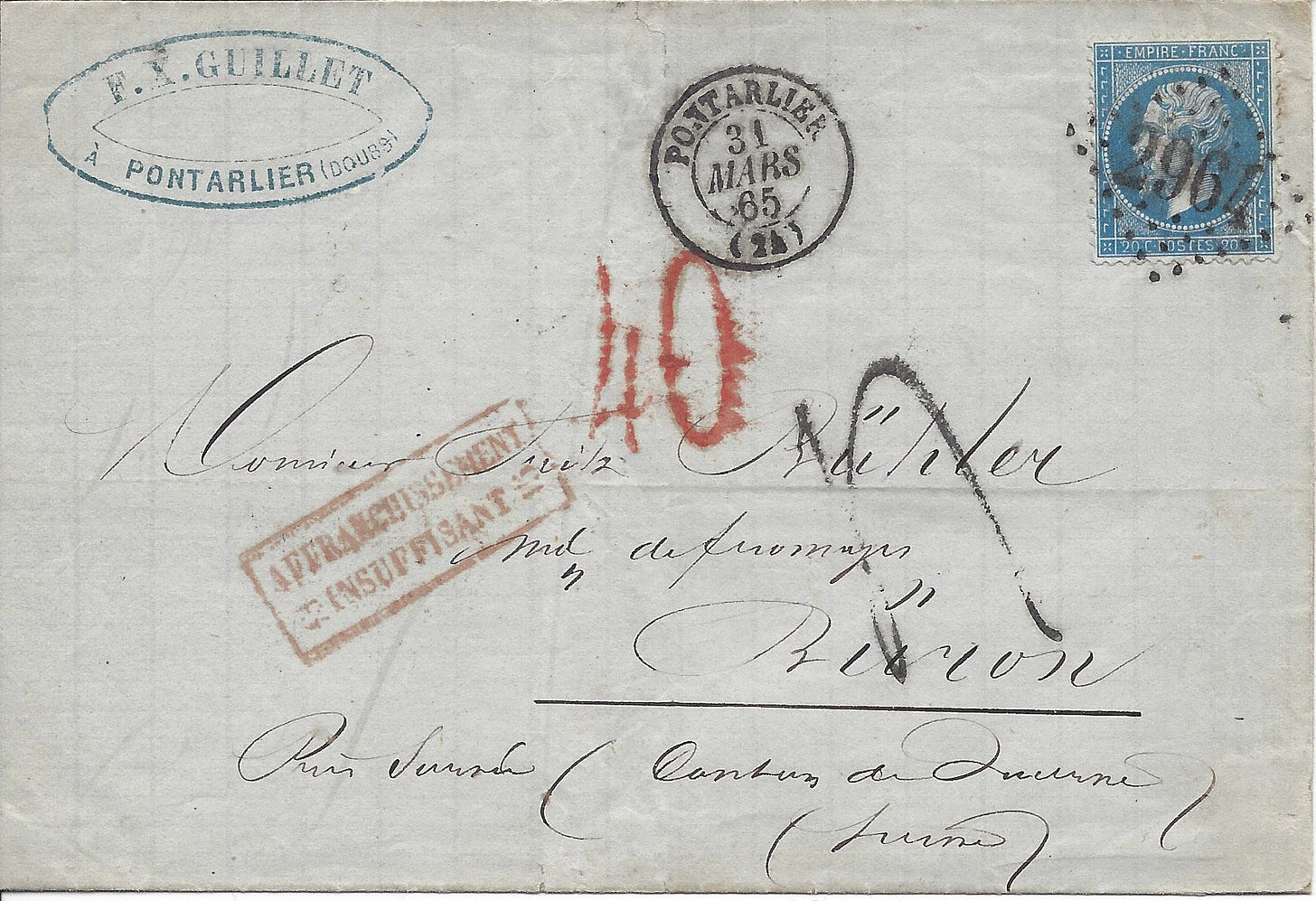

Here is another letter with the French “Insufficient Postage” marking in red. This letter, mailed in 1865 from France to Switzerland has a 20 centime postage stamp that, I am guessing, the sender may have mistakenly thought paid the proper postage.

There were, at the time this letter was mailed, two letter postage rates in effect between France and Switzerland (Jul 1, 1850 - Sep 30, 1865). Most mail was rated at 40 centimes per 7.5 grams. However, there was a special reduced rate between border communities. This rate was 20 centimes per 7.5 grams.

Also, the French internal letter mail rate for a simple letter weighing no more than 10 grams was 20 centimes. So, it isn’t hard to understand that a person might be prepared to pay that much for most of their letters.

F.X. Guillet of Pontarlier was probably used to using both the domestic letter rate AND the border rate because Pontarlier is approximately 10 km from the border with Switzerland. Unfortunately for Guillet, the border rate only applied when both the origin and destination were no more than 30 km apart. The intended destination for this letter, near Sursee, was over 200 km distant.

There is no way to tell if Guillet did not understand how border rates worked or if they simply paid what they usually paid and didn’t remember to add more postage. Their mistake forced the recipient to pay for the letter (40 rappen or centimes) because short paid mail between France and Switzerland was to be treated as completely unpaid.

Dear Monsieur Guillet, I received your letter of March 31. See enclosed bill for postage due to me because you don’t appear to understand how postage rates work. Yours most unaffectionately, M. Ruhler

P.S. Yes, I know it cost me just as much to send you this letter. But I feel so much better after sending you this note. I would have called, but the phone hasn’t been made commercially available yet.

4. Changing borders changed postage payment options

Our next cover that illustrates partial payment of the required postage was mailed from Milano (Milan) to Mantua (Mantova) in 1860. There are two 20 centesimi stamps paying a total of 40 ctsm in postage. But, there is also a big, bold “5,” that indicates that there was postage due from the recipient.

To understand why some of the postage was prepaid and some was not, I need to give you a VERY brief history lesson.

The Kingdoms of Lombardy & Venetia were under the control of the Austrians according to the treaties signed after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Both Milano and Mantova were in Lombardy at that time. Letters between the two cities would have been internal and easy to fully prepay.

Things changed in 1859 after the second war of the Italian Risorgimento (Italian Unification). The Armistice of Villafranca on July 11, 1859 ceded Lombardy to France. France then ceded Lombardy to Sardinia in exchange for the Duchy of Savoy and the County of Nice (Treaty of Turin on March 24, 1860). Venetia, however, remained with Austria until 1866 - and Mantova was included in that territory.

When this letter was sent, Milano was part of the growing Kingdom of Italy and Mantova was part of Venetia, which was under the control of the Austrians. Needless to say, things were unsettled between Austria and Italy and there wasn’t a postal agreement that allowed for full prepayment of letters that crossed the border.

The two postage stamps (40 ctsm) paid the cost of mailing a letter to the border of Venetia. The recipient had to pay 5 soldi on delivery, which was the postage rate for a local letter (Mantova was right next to the border).

The internal postage rate in Sardinia (Kingdom of Italy) was 20 centimes for a letter weighing no more than 7.5 grams. So, this letter must have weighed more than 7.5 grams and no more than 15 grams. Austrian rates were determined by the loth (about 15 grams). So, this letter qualified for a double letter rate in Italy and a single letter rate in Venetia (Austria).

5. The mail route option didn’t allow full prepayment

Here is another letter that has a combination of postage to prepay some of the costs and a due marking to pay for the rest of the postage. This time we are looking at an 1868 letter mailed in Geneva, Switzerland to Rome - then in the Papal States.

The postage applied on this cover is 35 centimes and a “P.P.” marking indicated to the Rome post office that it was only paid to the Papal border. The clerk in Rome scrawled a "20" to alert the carrier that they should collect 20 centesimi from the recipient at delivery to pay the postage for postal services in the Papal territory.

There actually WAS a way to fully prepay a letter from Geneva to Rome, but that would have required more postage to go through France and then take a coastal steamship from Marseilles to Rome. Not only would that route have cost more, but it would have been slower than this overland route. So, it makes sense that they opted to split the cost with the recipient - especially if time was an important consideration.

There was (again) a political issue that prevented full prepayment if a person wanted to use the overland route. The Pope refused to recognize the Kingdom of Italy, which meant the Papal postal system was not allowed to negotiate and execute a postal convention for mail that went to, from, or through the rest of Italy. Because the Swiss and the Italians had an agreement, a person could pay for that portion of the trip - up until the letter got to the border with the Papal States.

For those looking for details on rates here they are (and if you aren't, feel free to skip):

Paid to Destination via Marseille

70 centimes per 7.5 grams : Oct 1, 1865 - Dec 31, 1870Paid to Papal border via Florence

35 centimes per 10 grams : Jul 1, 1862 - Oct 26, 1870Postage due Papal Post if via Florence

20 centesimi per 7.5 grams: Sep 21, 1867 - Oct 26, 1870

6. There was an option to split the costs

There were also times when the person sending a letter selected an option, on purpose, to split the postage cost. The envelope shown above was mailed from the US via Prussian Closed Mail to Switzerland in 1866. This was a time when there were several options for sending a letter fully prepaid between these two countries - including the Prussian mail! Instead, this person appears to have intentionally opted for partial payment.

The Prussian system is interesting in that it would allow mail from the United States to be paid 'up to the outgoing border.' In other words, the sender could opt to pay the 28 cent rate to get a mail item to any location within the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU). Once it reached a border, it would be sent on as an unpaid piece of mail from the Prussian system to its destination - which was Switzerland in this case.

This rate was not advertised in the postal rate tables at the time, so the clerks or patrons had to be aware of other options that were not shown in those tables. The Prussian mail clerks, however, were quite aware of this option and put a blue box marking on the envelope that reads “Franco Preuss. Resp. Vereinsl. Ausg. Gr.” (Outgoing mail paid only to border)

Since the letter was not fully paid to the destination, the recipient was required to pay 10 rappen (or centimes) in Swiss postage for the privilege of receiving their mail. If you didn’t notice it, look again and I think you’ll see the big red “10” in crayon on the cover.

And there you go! Another Postal History Sunday in the books. And I think I would be right in saying I didn’t short any of you with today’s issue.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

It is truly amazing how well we can learn to estimate things like weight and distance with practice!

Another very interesting history - which teaches us a bit about foreign relations as well as mail!!