A common ritual for members of rural midwestern United States farming communities is annual attendance at the county fair. I grew up in a larger Iowa town that orbited around a certain washing machine manufacturer, so I was not among those who marked the progress of the summer months with a county fair. But, my family did attend the Iowa State Fair most summers, which provides me with a fair share of childhood memories as a reference.

Now I live on a small-scale, diversified farm and can relate more to the atmospheres of small-town celebrations and county fairs. The events all have their fair share of entertainment and fried food opportunities. But, it’s the wide range of competitive categories in county fair (or similar event) that are going to grab our attention today.

Best bantam-sized chicken. Best flower arrangement. Best quilting project. There is probably a category in existence for most anyone who might like to participate. Since this is Postal History Sunday, I thought it might be interesting to transport ourselves back 180 years and see what some of these agricultural “competitions” were like then.

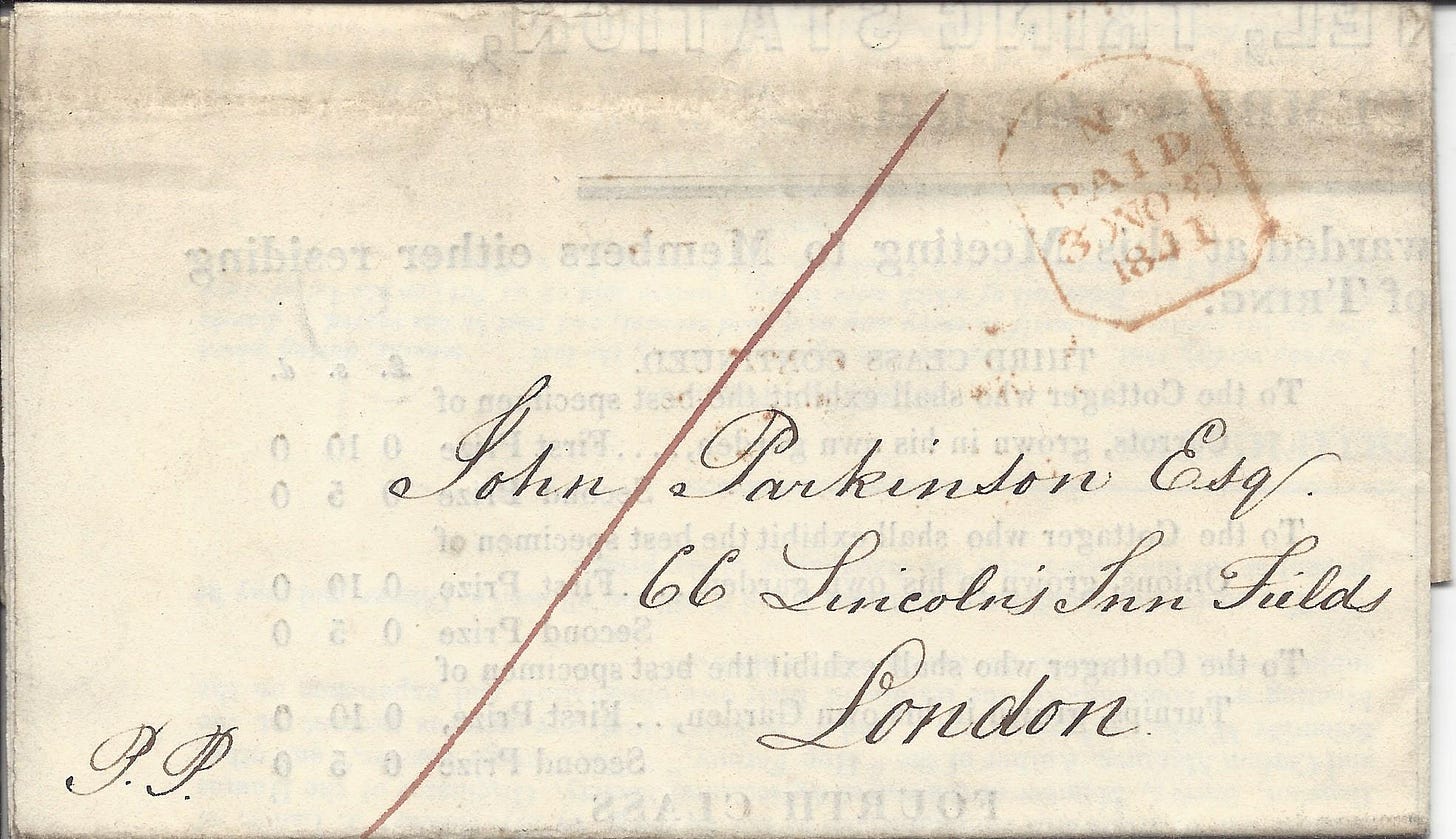

Shown above is a folded letter that was sent prepaid from Tring (England) to a London address (66 Lincoln’s Inn Fields). Oddly enough, this preprinted flier was sent to a lawyer who was residing in the Powis House in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. And, I say “oddly enough” because the content doesn’t seem to me like something a lawyer would be worrying much about - unless, perhaps, Mr. Parkinson was born and raised in Tring. Let’s keep our ears and eyes open because I suspect we’ll get some hints that will help us there.

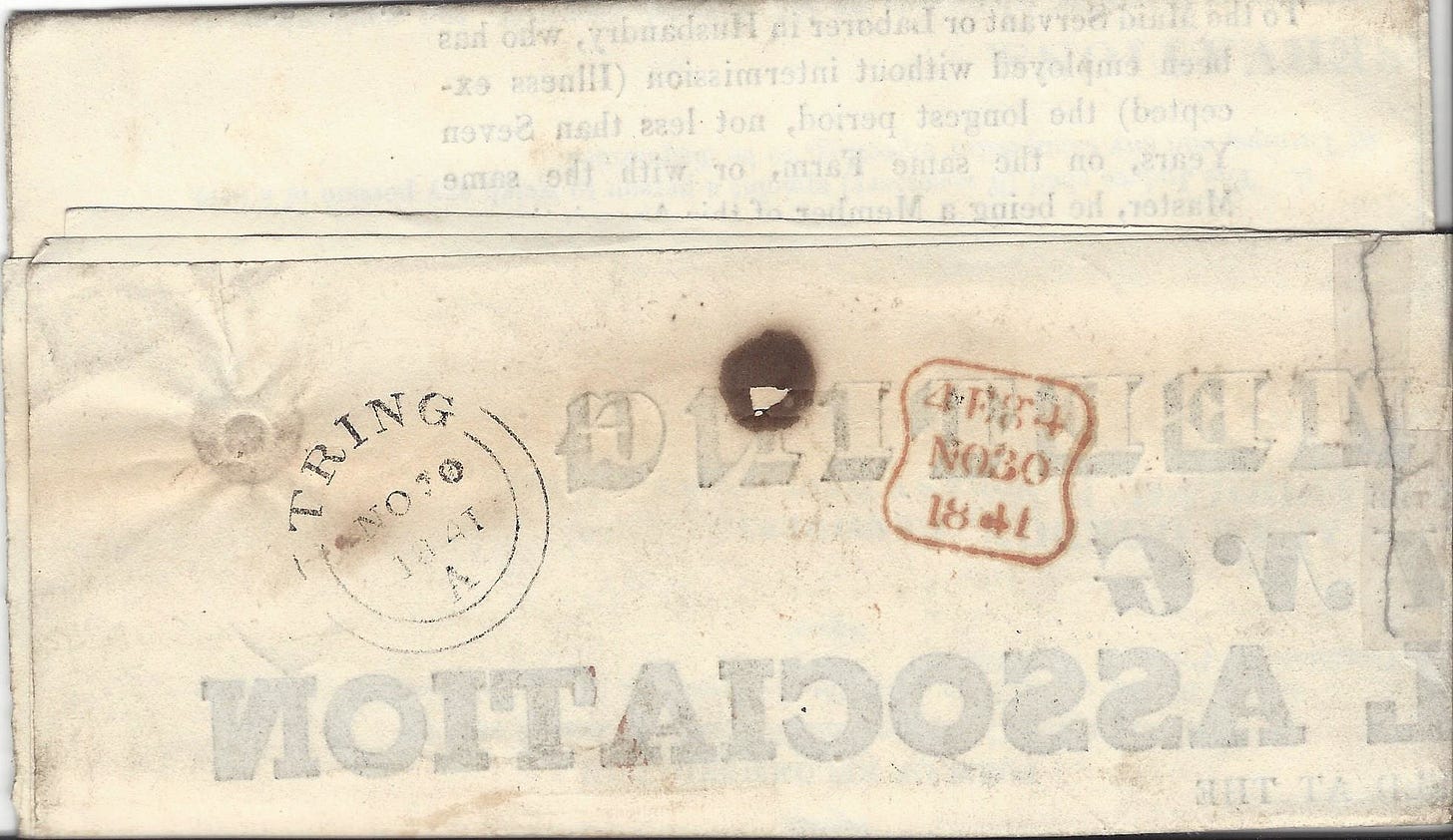

Before I move on to the contents, let me first look at the postal history surrounding this particular item. The origin postmark for Tring is on the back of the folded letter along with another red postmark.

The date on both the Tring and the two red postmarks are the same (Nov 30, 1841), which makes some sense since Tring is not far to the northwest of London. In fact, there was a rail station to the East/Northeast of Tring where the mailtrain went by on a regular schedule.

The cost for a simple letter weighing no more than a half ounce was 1 penny. The red slash on the front probably indicates that amount (1 d). The combination of the red ink for two postmarks and the word “paid” in the marking on the front tells us the penny in postage was prepaid and not due when Mr. Parkinson received this piece of mail.

For now, that’s enough of the postal history portion - keep reading and we’ll have some “bonus material” that will expand on it a bit. For now, I am much more attracted to the “inside” of this folded letter.

This cover consists of one large piece of paper (about 20 inches tall by almost 13 inches wide) that was folded over itself. Since the paper is printed only on one side, it was possible to fold it up in such a way that the outside of the cover would not have any printing. This provided a clean surface for placing the mailing address and for postal markings to be applied as the letter traveled through the British Postal Service.

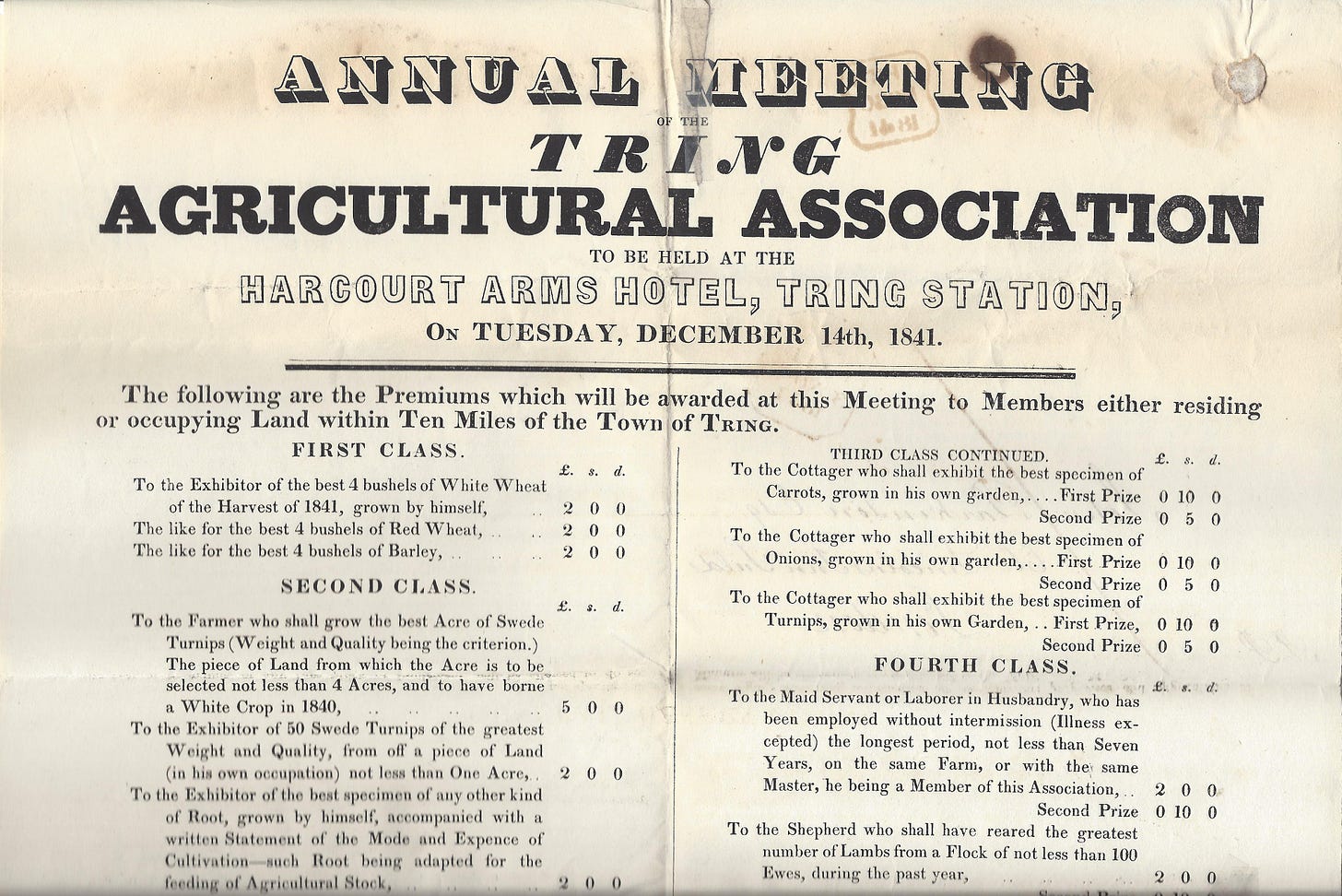

The letter was advertising the upcoming Annual Meeting of the Tring Agricultural Association. And, if you take a closer look, it has a little bit of that “county fair” feeling to it.

The top half of the flier - if that is an adequate description, it could almost qualify as a poster - provides a list of the possible ways a person, living within ten miles of Tring, could enter to win prizes by showing off some of their own “agricultural prowess.” The best “4 bushels of Barley” could walk away with 2 British pounds in cash! A cottager could bring in samples of their own carrots and onions to win ten shillings for first and five shillings for second.

The idea of farmers showing off the production of small grains, such as wheat and barley is probably not foreign to most people in today’s world. But, I suspect there might be some surprise and confusion that “Swede Turnips” held not just one, but TWO categories in this particular event. The first category being a judgement for the entire yield for an acre and the second being a selection of 50 turnips (presumably selected as the best of the batch).

If you live in the US, as I do, you would recognize these as rutabegas (and not turnips) and they are said to have their origins in Sweden. For the time being, I’ll accept that as reasonably accurate, but I haven’t spent much time verifying that claim.

If you look carefully at the crops being judged, you should see a theme. They are all late season and storage crops (carrots, onions, potatoes, etc). This makes even more sense when you consider that this meeting occured in December, in England. Not exactly the time of year for tomatoes, flowers and other warmer weather crops.

Growing root crops like Swede turnips is a practice that was still being used by many farmers as early as a generation ago in the midwestern US, but you would be hard pressed to find a larger-scale farm growing this crop today. A farmer could plant root crops, like mangels, carrots and, yes, Swede Turnips for the express purpose of feeding livestock.

These root crops were often be intercropped with other cash crops, like corn. Once the cash crops were harvested, the animals could be put out to the field to graze. And, of course, the farmer could dig the roots and store them for winter feed if they prefered.

So, it isn’t a surprise to see that many of the categories for this event in 1841 focused on larger volumes of storage crops that could feed the animals - including, possibly, the humans!

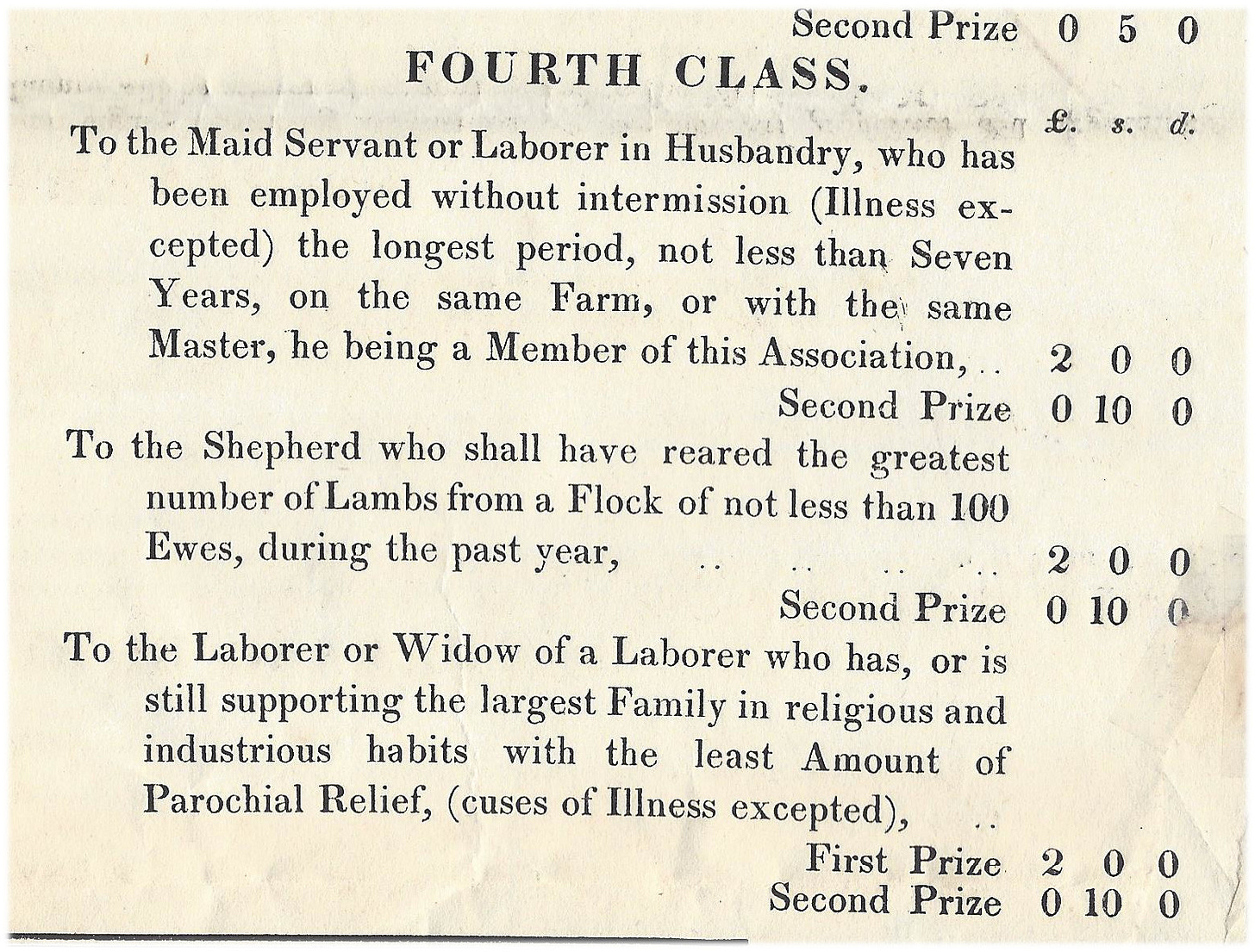

There were, apparently, four different classes for awards at this event. The first and second classes focused on the farmers and individuals who owned larger portions of land. The third class provided an opportunity for “cottagers” to enter some of their garden’s production for judging. But, the fourth class was something altogether different.

The fourth class sought to find some way to include individuals who did not own land. These were the laborers and servants in the Tring area. In other words, these might be individuals where two pounds or ten shillings could make a significant difference in their lives. But the categories for judging leave much to be desired.

The first rewards the two individuals who have been employed the longest by a “Master” who was a member of the Tring Agricultural Association. That seems to me to be a way to breed some discontent if the award is a foregone conclusion each year. At least it is fairly easy to judge because little is left to interpretation.

The Shephard raising the greatest number of lambs at least seems like an honest award for success in agriculture. But, how does one judge the last category?

The rules for entering this event for judging are found on the lower half of the flyer. This is where we begin to realize that this is not the same thing as our current county fairs. There is a very strong hierarchical structure being followed where those who are members (paid five shillings or more) can enter the first and second classes. Non-members need not apply to those categories. But, then again, people who couldn’t afford five shillings to be members also likely didn’t have the land to compete in those categories anyway.

The kicker here is that persons who wanted to enter in the third and fourth classes had to be recommended by a member of the Tring Agricultural Association. And, just to avoid having one member recommend every “cottager,” they limited recommendations to one per member.

Today, if I wanted to enter some of our produce in the county fair, I would just have to get my entry form and fee in on time. I’m sure they’d welcome each and every entry we wanted to try - even if they don’t know who we are.

There is a very short add-on in the “General Observations” section of this flyer that makes it clear that not just anyone can join the dinner (3 s 6 d for a ticket). But, if you happen to be recommended for classes three or four AND you win, they’ll let you join everyone else for some food. So, while this event has some of the qualities of a county fair, it is clearly a private event - not a public event like our county fairs have become.

I mentioned earlier that we might get a clue as to why John Parkinson, lawyer in London, received a mailing about this event. It is likely that Parkinson or his family were a land-owners in the Tring area. Perhaps they were even members of this group. If they were, it would make perfect sense that information for the Annual Meeting would be sent to him.

Shown above is a contemporary flyer from the United States in 1840 promoting an Agricultural Society fair (the 2nd annual event!). This probably fits the more standard modern definition of a county fair in that anyone could enter. To understand why it is different, we should consider some fundamental differences between Illinois and Tring near London in the 1840s.

Tring had, obviously, a much longer history of European culture than Illinios at the time. As such, the societal structures with their hierarchy were firmly in place. Many people who sought to get out from under those structures were immigrating to the US and moving to places like Greene County. There was at least some sense that everyone had equal status. As long as you weren’t a person of color or an Indigenous person (perhaps with some exceptions), opportunities were more generally accessible.

And, yes, if there was an entry fee you probably still had to have to pay to play. If you didn’t have the money, you were left out.

The event in Tring was held at the Harcourt Arms Hotel (soon renamed the Royal Hotel) near the Tring Train Station. This building was put up soon after the London and Birmingham Railway was completed to this point in October 1837. The hotel was likely completed in 1838. The building remains standing and has been converted to private flats - no longer serving as a hotel.

The actual location of the train station is actually 3 km to the East and a bit North from Tring. The rail line was not interested in serving the numerous small settlements along the route. Instead, they were attempting to find the best route that would accommodate the locomotives of the time. As it was, some of the area around the Tring station had to be trenched to avoid creating a grade that was too steep for the train.

Wendy Austin’s Tring Gardens, Then and Now provides a nice history of “gardens, gardeners and the horticulture society” in that area’s history. Austin claims that the Tring Agricultural Association was formed in 1840, making the flyer in this piece of postal history a very early artifact for this group. In other words, this could very well have been the first annual meeting of the organization - and no more than the second such gathering. This just might explain why some of the awards categories seemed a little odd. They were still trying to figure out how this sort of event should work!

The group was initiated with the goal of ‘promoting agriculture and horticulture and to reward industrious labourers.’ Austin stats that the event was held regularly for thirty years and was well attended and well run.

In 1868, a wealthy land-owner, Dr. Thomas Barnes, sponsored a class for those in less affluent circumstances. Eventually, this organization led to the development of a horticultural (flowers, fruits and vegetables) society and by 1892 the Tring Horticultural and Garden Show attracted as many as 500 people to the event. Awards were given for garden produce, bread, pastry and cooked vegetables, among other things (now it’s sounding more like a county fair!). By the turn of the century, the annual event included sporting competitions and live music.

Bonus Material

For those who are interested in postal markings, British postal markings are quite an area of study and there are numerous references available to those who would like to learn more. The Great Britain Philatelic Society has digitized several reference books and made them publicly available on their website.

The marking on the front of this folded letter was applied in London. There was a Paid Letter Office that would process incoming letter mail from outlying communities, checking that the postage was, indeed, properly paid. The paid letters would come in with a corresponding “letter bill,” which was a list of paid letters and the amount of postage paid for each. Once it was determined that the letter was properly paid, a paid marking like this one would be applied (see page 25 of this resource).

The red marking on the back can be found on page 80 of the same resource linked in the prior paragraph. This is identified as a receiving postmark for the London post office. These sorts of postmarks are usually applied at the time a letter is taken out of the mail packet or mail bag and it serves the purpose of providing accountability for mail delivery process. Receiving postmarks are most frequently found on the back of mailed items in Europe and North America during this time frame.

I personally, do not know if this marking was applied before or after the other marking. If someone does know the procedures used better than I, feel free to let me know! However, I did take note that the Hendy book I have linked here suggests that the use of red ink for paid mail and black ink for unpaid/short paid mail went into effect on January 1, 1836. This is a fine illustration of how postal history facts gain definition as I gain more experience. I have been aware of the color designations for some time and recognized that it became regulation at some point in the 1830s or 40s. Maybe I’ve read this fact before but I had no cause to remember it.

Maybe I’ll forget it tomorrow. But, since I’ve written it into a Postal History Sunday and the odds of remembering just went up! Just don’t ask me when I’m harvesting the tomatoes this week. I’m going to want to pay attention and select the best for the county fair…

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Thanks Rob, and best to Tammy as she continues to "heal up and hair over"! I am old enough to remember when the Agricultural Fair slowly morphed into the "County Fair", with less emphasis on crops and livestock. Still there though!!