I work with words on a regular basis. Because I work with words, I often contemplate their meanings and wonder if they actually mean what I think they mean (words like “inconceivable” perhaps?). For example, I call myself a postal historian, but what does that mean?

I became a postal historian because I was interested in collecting old envelopes and folded letters (covers). So, you could say a postal historian is someone who collects postal artifacts and you probably won’t get an argument from many people. But if all a person did was accumulate covers, would that qualify?

In my own mind, I feel I have been able to qualify myself as a postal historian because I like to explore, learn and share about the historical aspects that surround a particular piece or a group of postal history items. I will take a wild guess that most people who do collect postal history can’t stop themselves from learning a fair amount about what they gather. It comes with the territory. Perhaps it’s just a natural progression.

One of the aspects of collecting for some people is the acquisition of a representative example of each “different” thing - based on either a generally accepted list or a personally developed list. Coin collectors often collect an example from each year a coin is minted. Stamp collectors often seek an example of each design issued. Even postal history collectors can create a “list” of thins to seek out.

Today I thought I’d share an example of one way a person could create their own list and the motivations behind it. Grab your favorite beverage and put on the fuzzy slippers. Push those troubles aside for a while and get comfortable.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

Watching Postage Rates Fall in the 1800s

The simple act of sending a letter in the early 1800s could be a bit of an investment. According to this article found on the Proceedings of the Old Bailey, a working family would need about 20 shillings a week in the late 1800s to get by. The folded lettersheet shown above cost the recipient 2 shillings and 3 pence at the point of delivery. In addition to that, the sender had to pay 13 decimes (1 franc & 30 centimes) just to get the letter on its way from Tarbes, France, to Aberdeen, England in 1825. On top of that, there was an additional 1/2 penny surcharge for the Scottish mail (Aberdeen N.B. - North Briton). For comparison, an inexpensive, unfurnished room could cost 1 to 2 shillings a week to rent.

Hm. Let’s see. Pay for this letter or pay for the room I live in? Which should I choose?

In the present day (for comparison) a studio apartment in the Chicago area would cost, on average, $350 per week. To send a letter from the US to England or France would take $1.65 in postage. I know these are rough equivalents because a studio apartment is not the same thing as a single room in the 1800s. And, mailing a letter from the US to England is definitely not the same as France to England. But, I think you get the point. The relative cost of sending or receiving a letter vs renting a place to live has changed a fair bit.

This brings me to the whole point of this article. I can, if I wish, make a list of covers to collect that illustrate for me the movement to affordable postage that occurred from the 1840s until the development of the General Postal Union in 1875. While postage rates continued to decline a bit after that point, things had mostly settled where costs for the postal services were covered at a rate that allowed most people access to writing and receiving letter mail.

1843 - 1854: Mail between France and the United Kingdom

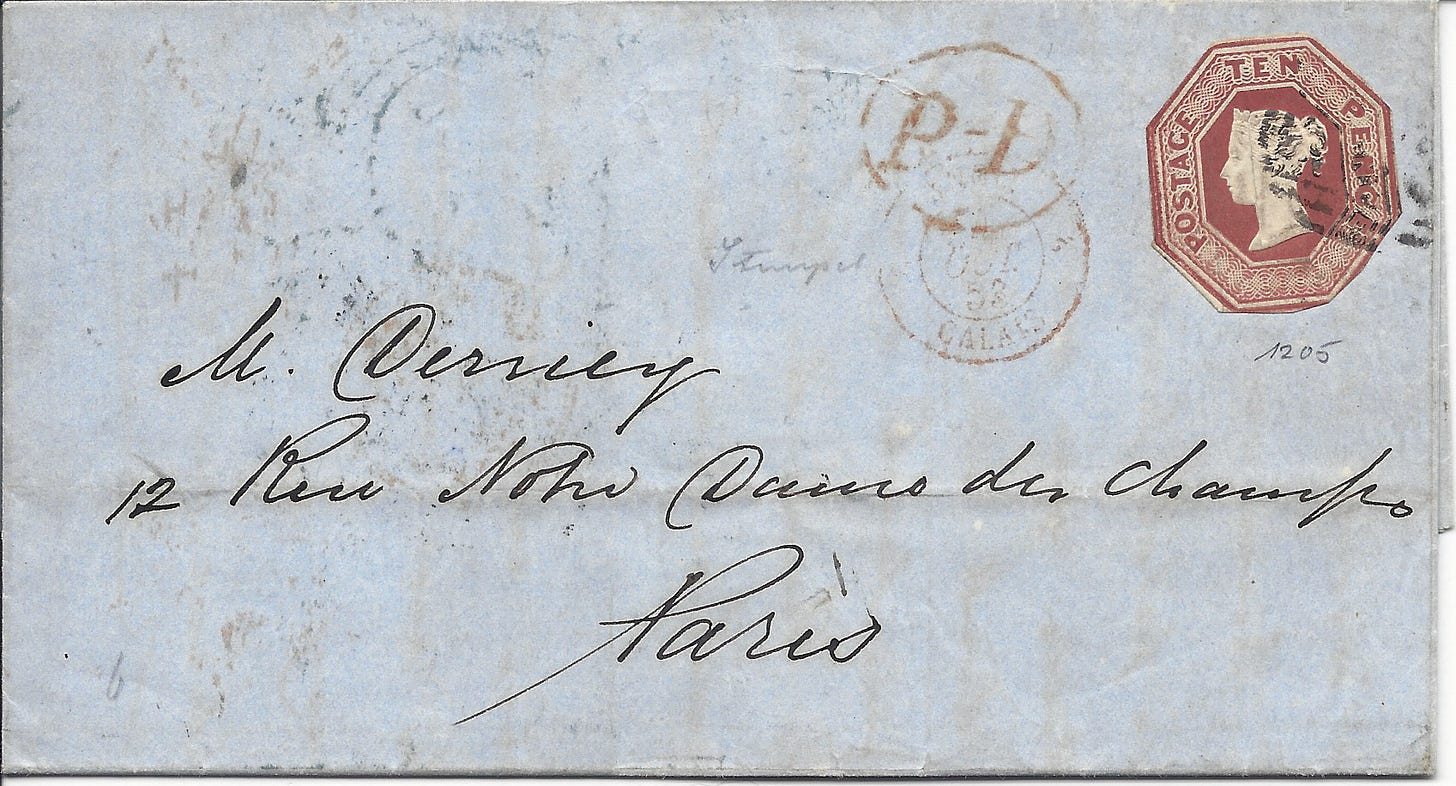

In 1843, the British and the French signed a postal agreement that set a much lower postage cost for mail between the two countries. For our first cover, the letter cost 1 franc 30 centimes for the French postage and 2 shillings 3 1/2 pence for the British and Scottish postal costs. Our second letter, shown above, was mailed in Sheffield on Oct 1, 1853. It was sent under the regulations of this new agreement and was fully prepaid to go Paris, France, with a single stamp that represented 10 pence in postage.

Like the first letter from Tarbes, there was a very definite line that determined where the postage revenue went. The new agreement set the British portion at 5 pence per 1/2 ounce in weight. The French portion was 5 pence per 1/4 ounce in weight. So, this letter must have weighed no more than 1/4 ounce (5 pence for the British and 5 pence for the French).

This interesting agreement actually seems odd if you look at the rates based on the weight of a letter.

Up to 1/4 ounce - 10 pence

Over 1/4 ounce up to 1/2 ounce - 15 pence = 1 shilling 3 pence

Over 1/2 ounce up to 3/4 ounce - 25 pence = 2 shillings 1 penny

Over 3/4 ounce up to 1 ounce - 30 pence = 2 shillings 6 pence

and so forth

For a fair comparison, the 1825 letter probably weighed more than 1/4 ounce, but it does not weigh more than 1/2 ounce. So, if it were mailed in 1853, it would have cost 1 franc and 50 centimes (the French equivalent of 1 shilling 3 pence). But, that is still significant savings in postage costs. If the cost of the 1825 letter were converted to French currency, it would have come to 4 francs.

In short, it isn’t a bad estimate to say that postage costs for a letter between France and the UK were at least half of what they were in 1825.

1855 - 1869: Letter rates continue to fall

A new postal agreement went into effect in 1855 that further reduced the cost and simplified the rate calculations. The French could send a letter to the UK for 40 centimes per 7.5 grams. Persons in the UK could send a letter to France by paying 4 pence in postage for each quarter ounce. These rates were linear, so a letter that weighed more than 7.5 grams, but no more than 15 grams would cost 40 centimes times two - 80 centimes.

It just so happens the folded letter shown above has four 20 centime stamps to pay the postage for a double weight. Once again, we are looking at postage costs that are less than half of what they were for the previous agreement. This is a rapid decline in postage costs considering the 1843 rate structure only lasted for nine years before this new structure was put into place.

There were several reasons the rate reductions were possible. To understand them, we need to consider some of the reasons. One of them was the rapid evolution of fast transportation provided by the development of railways in Europe at the time.

If you look at the line graph shown above, you can see a tremendous boom in the development of railways in Britain in the 1840s. In fact, there continued to be aggressive additions to the existing lines through the mid 1860s. France (and many other European nations) saw similar growth curves. France started later, but developed a significant number of railways based on a “star design” with Paris at the center.

Instead of mail being carried by horse-drawn carriages, it could be taken on a train with a rail car often dedicated to that service. Because a train could have income from more sources (more passengers and cargo) and it could move the mail faster, the actual cost to move mail from place to place declined.

The folded letter shown above is another example for this period, but it shows an item traveling in the other direction - from the UK to France. Mailed on February 11, 1867 in Manchester, England, this letter traveled by train to London and then crossed the English Channel. It was placed on the mail train from Calais to Paris the next day and was likely delivered to the recipient on the 12th. For comparison, our first letter was written on the 24th of September and arrived in Scotland on the 6th of October - 12 days later.

This letter is interesting because it was very clearly a “heavy” piece of letter mail. The postage applied totals 1 shilling and 8 pence (20 pence), which indicates to us that this was a quintuple weight letter (5 times weight). In general, heavy letters were far less common than simple letters (letters that weighed no more than the first weight increment). So, it is always enjoyable for a postal historian when they can find one.

1870 - 1876: Prices begin to plateau

The next postal agreement set even lower postage levels, but the reductions were far less drastic. But this time, the price drop was accompanied by an increase in the weight increment. The French rate became 30 centimes for each 10 grams (up from 7.5 grams) and the British rate was 3 pence for each 1/3 ounce (up from 1/4 ounce).

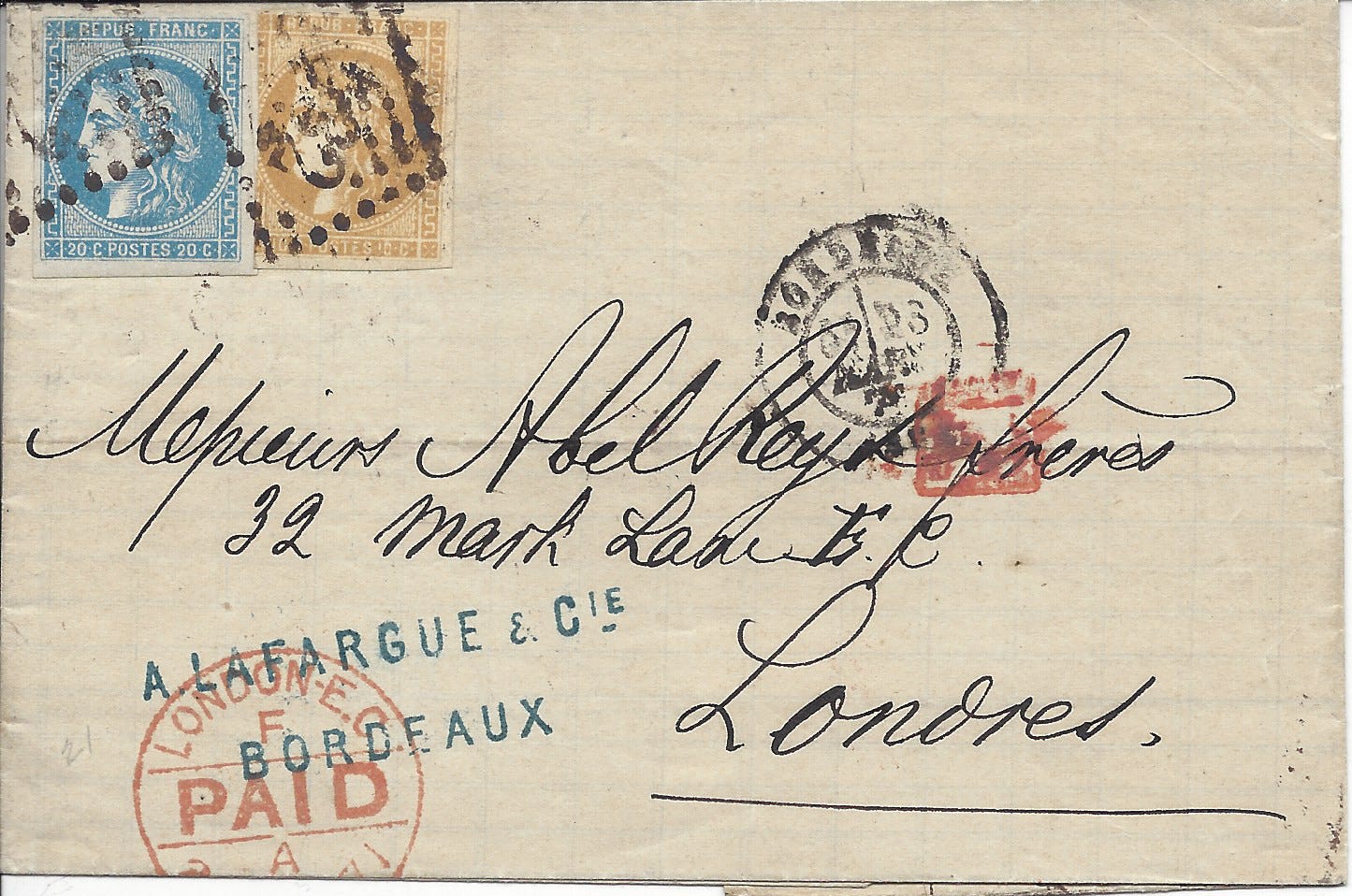

Our next folded letter was mailed in 1871 from Bordeaux, France to London (Londres). Two postage stamps, for a total of 30 centimes were applied to give evidence that the postage was paid.

The postage stamp provides us with another reason for the reductions in postage during this time period.

Sir Rowland Hill is a name that happens to be known by many postal historians and philatelists as he is often credited with the invention of the postage stamp (though this is an over-generalization of how postage stamps came to be). But, more importantly, Hill was on the forefront of postal reforms that led to cheaper postage, making it possible for more of the populace to avail themselves of this service. He wrote "Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability," and the United Kingdom implemented those reforms in 1840. The link is to the 3rd edition published in 1837.

One of Hill’s arguments was that the system promoted collection of postage at the destination. This often resulted in unpaid postage for refused mail, slow mail delivery, and mistakes due to the complex system. Just think a bit about our first letter. The sender had to pay the French postage. The recipient had to pay the British (and Scottish) postage. And, the recipient could have refused the letter, which means the British post was not going to get paid for their part of the deal!

The development of the postage stamp to simplify the prepayment process was as good as any reason for the deflated costs to send a piece of letter mail.

That brings me to the stamps on this particular folded letter. The design is a depiction of Ceres, a very non-political figure intended to symbolize prosperity. As Paris was being surrounded in September of 1870 by the Prussians, the rest of France was cut off from the supply of postage stamps printed there. To make the story shorter, stamps based on the first French postage stamp design were printed in Bordeaux (southwest France). Hence this issue of stamps is often referred to as the Bordeaux Issue (we can be so clever, can't we?). These stamps were printed using lithography rather than the finer engraved printings of the earlier issues.

Once the siege was over, the Ceres design was continued, but they were printed in Paris using engraved plates, rather than lithography. These stamps simply illustrate an adaptation required by extenuating circumstances - something postal historians also love to explore!

I will close with a letter sent from London to Lyon, France in 1871 - just to show you something going the opposite way during this period. The letter above bears one stamp that represents three pence in postage and the other is for four pence. The rate was 3 pence per 1/3 ounce, so why is there seven pence in postage paid?

Well, the clue we need is very easy to see - but it might not mean anything to you. The “L1” in a box tells us that a late fee was collected (1 penny) for this piece of mail. That leaves us with 6 pence, making this a double weight letter weighing more than 1/3 ounce and no more than 2/3 ounce.

The London post office had closing times for the mail to various destinations - such as France. This was to insure that all letters received by that time would not miss the transport to the port where it would travel on a steamer across the English Channel. However, the London post office provided a service to allow latecomers to pay an extra fee to get their piece of mail on that transport. Of course, there was a point when a letter was truly “too late” and no amount of extra postage was going to make a difference. But this letter apparently was late, but not too late.

And speaking of late, it is getting late in my part of the world. So, I will call it a day and send this edition of Postal History Sunday out into the world for your enjoyment!

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Rob,

You and Wayne Youngblood are very inspiring philatelic authors and historians. Afraid I'm not in a position to subscribe nor do much postal research until I retire but wanted to express my appreciation for your writings.