Detours

Postal History #185

Today we're going to transport ourselves back to the mid 1860s for this week’s Postal History Sunday. For those who have enjoyed a few Postal History Sundays, you might not be surprised by the time period because that's historical time frame I am most familiar with. And if you are new, welcome! I hope you give yourself the opportunity to put those troubles out of sight for a while as I do my best to entertain you with something I enjoy - postal history!

Today (March 2024), you could send a simple letter, weighing no more than one ounce, from the United States to any other country in the world for $1.55. Send a letter to China? $1.55. Send it to Argentina? $1.55. Send it to Italy. $1.55.

But, in the 1860s, the choices were a bit more complex. If you wanted to send a simple letter from the US to Italy, it could cost 21 cents. Or 40 cents. Or 22 cents.

Here, just look at the table below for your choices:

How in the world were you supposed to figure out which postage rate to pay?

Well, first, you had to determine which PART of Italy this letter was supposed to go to. As recently as 1858, Italy was broken up into a number of independent states including Parma, Tuscany, Modena, Sardinia, the Papal States, the Two Sicilies and the Kingdoms of Lombardy and Venetia. By the time we get to 1863, the Kingdom of Italy included all but the Kingdom of Venetia and the Papal State around Rome. But, still, US postage rates were figured based on the old territories.

After you figured out which part of Italy the destination belonged in, you might have a choice as to which countries you would send the letter through to GET to Italy in the first place. You could choose between sending it via France, Prussia, Britain, Bremen or Hamburg. Each of these options cost a different amount of postage and sometimes changed increments based on different weight amounts.

To make it even more difficult, some routes were tied to particular shipping companies that crossed the Atlantic Ocean. You might get a better postage rate with a given choice, but there could be a significant delay if you didn't hit that shipping schedule properly.

And... I even simplified the options available to you a little just to keep it easy to understand.

Did I succeed? No?!?

Okay, let's just say you had lots of options and variables to consider. It wouldn't be a surprise if you were confused by it all. What often amazes me is that the foreign mail clerks were often able to make decisions for the best routing of mail despite the complexities. Most of the old letters I find from this period appears to have been handled without error.

Let's Send a Letter to Tuscany in 1863

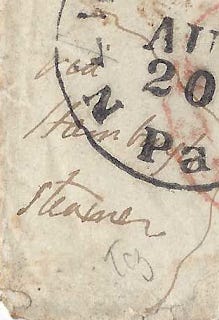

Here is a letter that was mailed in New Brighton, Pennsylvania on August 20, 1863. Thirty cents of postage have been applied to the letter and it was accepted as fully paid. Exactly which rate was this person trying to pay? I don't see a 30 cent rate anywhere in that table!

The letter is addressed to Florence, which is in Tuscany, which would qualify as part of the northern part of Italy. So, we have two choices on that table. The first choices is a 40 cent rate for a letter weighing nor more that 1/2 ounce via Prussia. The second is a 28 cent rate per 1/2 ounce via Bremen or Hamburg. The third is a 21 cent rate per 1/4 ounce via France.

We can eliminate the Prussian rate because it was higher than 30 cents and the “PD” in a box tells us it was considered to be paid in full. So, our options are Bremen, Hamburg or France.

To make a long story shorter, I'll just tell you! The sender was attempting to send this item via the Hamburg mail service, so the postage rate would have been 28 cents per 1/2 ounce to get to Tuscany. BUT, for some reason, this item was sent via the French mail service at the 21 cent rate per 1/4 ounce.

So, the question is - how do I know all of that?

Two pieces of evidence seem to indicate that the person mailing this expected this letter to go via Hamburg. The first is the 30 cents in postage (a convenience overpay of 2 cents). The second are the words "via Hamburg steamer" at the bottom left corner.

This letter did, in fact, leave New York's harbor on the Hamburg Line's Saxonia. But, for some reason, the foreign mail clerk decided that the letter should go via the French mails (as indicated by the New York marking with the "12" cent credit to France). This is further confirmed by that red “PD” marking. It just so happens that this is a French postmark as is the round, Sept 4 marking in the center of the envelope.

Having postmarks that were known to belong to the French post office on the envelope is a pretty big hint that the letter went via France.

Why didn’t the postal services follow the mailer’s wishes?

I suspect some of you might agree with me that it could be a little frustrating to do all the work of making a choice, only to have someone else decide you were wrong and change your choice to something else! It’s fairly likely that the writer of this letter never knew that their choice to send it via Hamburg wasn’t honored. I suspect they really only cared that it got to Isaac Eugene Craig!

But, if they knew it could have gotten there for nine cents less in postage - maybe they would have cared. After all, nine cents in 1863 is worth the equivalent of $2.20 today if I use an inflation calculator. It’s not going to break the bank for most of us, but it seems like it’s enough to care about given the situation.

For this trip across the Atlantic, the HAPAG line’s Saxonia was scheduled to carry the mail, leaving New York City Harbor on August 22 (the red New York marking on the envelope confirms this date). These HAPAG steamers carried mailbags that were meant to go to and through France AND they also carried mailbags for letters sent via England AND they ALSO carried mailbags to go to Hamburg.

Each Hamburg steamer would make a quick stop at Southampton (England) and drop off mail that could go to or through France or England. After that the steamship would sail on to Hamburg.

For this particular trip, the Saxonia stopped at Southampton on September 3, dropping off mailbags that would go via England or France. It then took another couple of days to get to Hamburg, dropping off those mailbags on September 5.

So, the question still stands: Why did the New York foreign mail clerk make this decision to send a letter to Tuscany, Italy via France instead of Hamburg?

The short answer is that I cannot be certain. What we need to understand is that the foreign mail clerks were often aware of potential mail delays and would often override the expected route when two conditions were met:

the postage would also cover an alternate route.

they knew the alternate route would get the mail to the destination more reliably and/or faster.

It is possible that they had learned that letters via Hamburg were typically slower to Tuscany than those going through France. Maybe there was some sort of transportation issue on the route via Hamburg. Perhaps the foreign mail clerk had a brother working in the French postal system and he wanted to support him?

We can at least use the following facts to help us decide why this might have happened.

Mail traveling overland on trains was usually faster than steamships on water

Tuscany was on the west side of Italy, closer to France. Mail via Hamburg would typically enter in the northeast portion of Italy or northern Italy after going through Switzerland.

With the letter taken off the Saxonia at Southampton, the letter was already in Paris on the 4th of September, but the Saxonia still was not in Hamburg at that time.

It is possible this letter was already in the hands of the recipient on September 5. If it had been allowed to go to Hamburg, it might be a day or two before it arrived.

This seems to imply that mail via France would almost always be faster than mail via Hamburg. So, why in the world would a person mailing a letter to Tuscany pick the Hamburg route at 28 cents when they could pick the faster French route at 21 cents?

The key is in the weight increments!

The French rate changed every quarter ounce. The Hamburg rate every half ounce. So, if a letter weighed more than a quarter ounce and no more than a half ounce, the cost for a letter through France was … 42 cents.

Last I looked, 42 cents was bigger than 28 cents. That might be worth being a day or two slower on the delivery.

In summary, if you had a very light letter, you could send your letter via a faster route at cheaper postage. If your letter was heavier and you were ok with the delivery being a little later, you could save yourself 14 cents (that’s $3.43 in today’s money - you could send TWO letters to Tuscany today for $3.10 if that helps you any).

So, the person who mailed this letter actually benefited from the knowledge the foreign mail clerk had. The clerk knew that the letter could get to its destination a little faster because the letter actually weighed no more than a quarter ounce. The postage was already on the envelope, so nothing really lost on that front.

And maybe that extra day or two was really useful - but you might have to learn that when we get to today’s “bonus material.”

How about a letter to Naples in 1866?

Below is a folded letter on blue paper that was sent from the United States to Naples in southern Italy. Even though the Neapolitan area had been a part of the Kingdom of Italy for a few years, postal rates in some cases still treated this as a separate entity.

The letter went through the New York foreign mail office and was slated to leave via the North German Lloyd ship called America on July 21. It would stop at Southampton on July 31 and go on to Bremen on August 2.

The scrawl in black ink at the top of the envelope reads "via Hamburg or Bremen." Clearly, the intention was to send this item via one of those mail services at the 22 cent rate per 1/2 ounce. Like the first letter, it left on a steamship that was going to one of those two cities (Bremen this time). But, like the last letter, it was also off-loaded at Southampton and sent via the French mails and their 21 cent per 1/4 ounce rate.

Why? Was it for the same reason?

The short answer is “no.”

There was this little thing that is often referred to as the Seven Weeks War (Austro-Prussian War) going on in 1866. Technically, the final battle of that war was July 24. But, at the point this letter was mailed (July 21), the postal clerk in New York knew that the route from Hamburg or Bremen to anyplace in Italy was going to be uncertain. So, they re-routed this letter via France.

Shown below is a good graphic summary of the conflict. It takes a moment to get used to the animation, but you can run it more than once if you like. Take note that there is conflict in northeast Italy and in Germany that would have blocked Bremen and Hamburg routes to Italy.

This is an excellent example of how world history is reflected in postal history. The mechanics of how a letter got from place to place were frequently modified to respond to armed conflict, natural disasters and transportation issues. So, when you find an old piece of mail and it doesn’t seem to follow the pattern that typical letters of the time followed, it’s a good sign that there is a link to a major event along the route the letter was destined to take.

Bonus Material

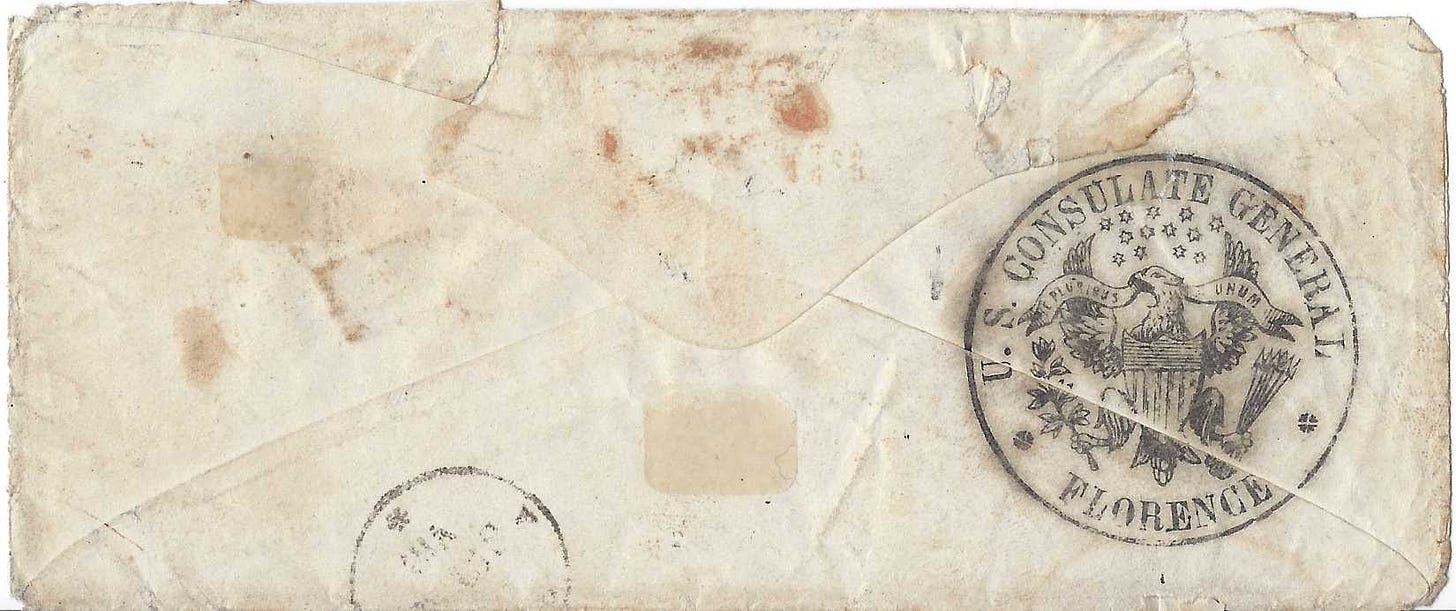

There is a fancy circular marking that is not a postal marking on the back of our first cover. It was applied at the U.S. Consulate General's office in Florence. The Consulate General was (and still is) "responsible for the welfare and whereabouts of US citizens traveling and residing abroad." The existence of this marking gives us a clue that the letter was probably to a US citizen who was in Italy in July/August of 1866.

Isaac Eugene Craig was a painter who was born near Pittsburgh in 1830. He traveled to Europe and stayed in Florence, where he painted for many years, including 1866. The Art Market site includes the following in his bio:

Craig's exhibition record at the Pennsylvania and National Academies shows that he was in Pittsburgh in 1848; in Europe,1853 to 1855; Philadelphia, 1856; Pittsburgh 1857-58; College of St. James (MD) 1860; New Brighton (PA) 1861; and Pittsburgh 1864. Returning to Europe, he spent a year at Munich and then settled in Florence, where he was still working in 1878. Specialized in Old and New Testament subjects as well as history and genre.

This gives us an excellent match with our first envelope - which I will show again here:

Since Craig was in New Brighton, Pennsylvania from 1861 to 1863, it shouldn’t be too surprising that a letter from that town would be addressed to him. And, the bio clearly places him in Florence in 1866. It’s always good when the historical facts fit the information on the cover!

If you would like to learn more, or if you wonder what resources I use as I research postal history artifacts, here is one such item:

"United States Letter Rates to Foreign Destinations 1847 to GPU" by Charles J. Starnes, the Revised 1989 edition published by Leonard H. Hartmann.

This book is still recognized as the best resource for anyone seeking to find U.S. foreign destination postage rates during the 1847 to 1875 period. The tables take some getting used to and it becomes easier to use as you learn more about postal history for that period.

If it weren't for the efforts of people like Charles Starnes, it is entirely likely I would not have found this hobby to be as enjoyable as it is for me. So, thank you to the late Mr. Starnes and all others who have gone before me and shared the knowledge they have uncovered.

Thank you for joining me and I hope you have a fine remainder of your day and a good week to come.

Additional Reading

If you haven’t had enough, here are some additional related entries you might enjoy:

Speedy Delivery - PHS #71

Another Thing Leads to Another - PHS#130

On the Verso - PHS#113

It amuses me a little that Isaac Eugene Craig has caught my attention in PHS more than once!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. Some Postal History Sunday publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Strangely fascinating. I'm reading this from Nome Alaska, which makes me wonder how mail traveled around this state back in 1866...

As always, well done and a great read!