Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication.

Grab yourself a beverage of your choice, making sure that you keep it away from your keyboard or the paper collectibles! Have a seat or stand up if that's what you prefer. Push those troubles from your mind and take a few moments of your day learning something new. Meanwhile, I will attempt to regale you with a story surrounding some postal history I enjoy.

Perhaps, if we're all lucky enough, each of us will learn something new.

This week I felt like digging into a single postal history item in my collection. To be perfectly open about this one, I've done work on this cover before - but I felt compelled to work with it a bit more. This is not at all unusual. Sometimes I just want to get the basics for an item down and I'll recognize that I could certainly do more with it later. But, more often than not, I'll just run out of time and I leave the rest for later. If I am lucky, I will have taken some notes so I don't have to start all over again!

Before I go much further, let me recognize that many who read Postal History Sunday are not postal historians. So, I should clarify what I mean when I use the word cover.

A cover is essentially anything that surrounds or holds the contents being mailed to the recipient. You and I are most familiar with an envelope, which would qualify as a cover. In 1859, envelopes were gaining popularity but, most covers were actually a sheet of paper that surrounded the letter contents. Sometimes, the outer sheet included some of the letter content on the inside facing part of that sheet.

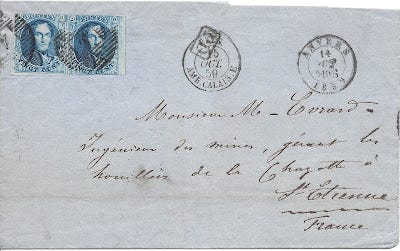

Our featured item happens to be a folded lettersheet from Antwerp (Anvers), Belgium to St Etienne, France mailed in October of 1859.

How It Got There

Markings on the cover:

Anvers Oct 14, 1859 - 9-10 S

partial marking on the back - unknown

PD in a box

Belg Amb Calais Oct 15, 1859 - E

Paris Oct 15, 1859 (on the back)

Mail between Belgium and France crossed the border at Tourcoing, Quievrain, Erquelinnes, Jeumont, Vireux-Molhain, Givet and Luxembourg. There were, of course, other crossings for local mail between neighboring communities that happened to be on opposite sides of the border. The crossings I mention above were for letters from and/or to destinations that were not border towns.

We can make educated guesses as to which border crossing was used if we look at the markings on the cover. Mail between nations at this time were exchanged between designated post offices. Aptly enough, these are called exchange offices and the markings they applied to pieces of mail are exchange office markings. (My! Aren't we clever with our names?!)

The exchange office markings on this cover indicate where the mail was placed in mailbags in Belgium and where they were taken out of those mailbags in France. Unfortunately, part of the reverse of this cover is missing. There is evidence of a partial Belgian marking that would have given us the Belgian exchange office. The French exchange office was the mail car (traveling or ambulant post office) on the train to Calais (Amb Calais). This leads me to the conclusion that this item probably crossed the border at Tourcoing.

How did I know that?

This is where I pull out the postal historian "voodoo magic" that is really just a combination of experience (seeing several covers from this period between these countries) and knowledge of some of the official documents that directed the mail exchange process in 1859. A little knowledge about the available rail lines at the time doesn't hurt either!

There is additional information in some of these postmarks that have the potential for further decoding. The 9-10S (9 to 10 PM) in the Anvers marking tells me when the train was due to depart. The E in the Calais marking references the team of clerks working in the mail car of the night train running from Calais to Paris. Go Team E! I wonder if they had their own cheer or chant or something?

How Much Did It Cost to Mail?

As of April 1, 1858, a flat rate of 40 centimes per 10 grams was established for prepaid mail from Belgium to France regardless of distance. This rate was effective until December 31, 1865 after which the rate was reduced to 30 centimes. If an item were sent unpaid, the cost would have been higher at 60 centimes due to be paid by the recipient.

The "PD" marking indicates the letter was "payée à destination," which translates to "paid to destination."

The obliterating cancellations were applied to prevent the re-use of the postage stamps by defacing them with ink. In this case, the obliterators or cancels are a round circle of bars with a "4" in the center. Many European countries assigned numerals in canceling devices to particular offices or towns/cities. The "4" in Belgium was assigned to Antwerp during this time period.

Who Was This To?

I am a person who sometimes looks at my own, or other person's writing, from a day or two ago and wonders "what does this say?" So, it is not so hard to understand why it might be difficult for me or anyone else to read the address panel on this cover from over 150 years ago.

Apparently, this is to a Mr. Evrard. And, after a bit of a struggle, I have concluded the rest of the address reads: "fungenieur des mines, gérant les houiller de la Chazotte." This tells us that Mr. Evrard was a mining engineer, managing the Chazotte coal mines near St Etienne, France.

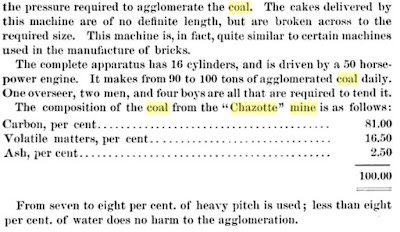

The Chazotte coal mine and Mr. Evrard feature prominently together in the mid-1800s largely because Evrard's inventions for coal washing and agglomeration received significant attention at the time. My basic understanding is that agglomeration was the creation of pressed coal bricks or blocks. Evrard's machine for creating these bricks is mentioned in this document reporting on the Paris Universal Exposition. Some of the relevant text from that document is below (see resource 2). You can click on the images to view them more closely if you wish.

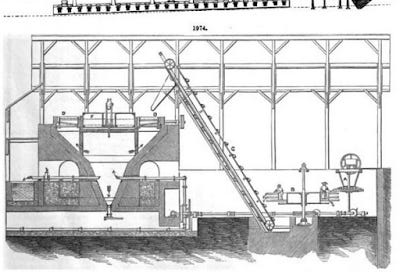

Evrard's innovations were apparently not limited to the agglomeration process as his design for coal washing is also featured in another contemporary document. Part of the idea of washing was to separate the coal from the pyrites, which are heavier than the coal. One of the figures showing the design of his coal washing system is shown below (resource 3):

As a kindred problem-solver, I can appreciate the approaches used for solving these production problems, even if I do not pretend to fully understand the entire process or the qualities desired for coal at the time.

Bonus Material

The mining region where the Chazotte mine was located is shown in the map above to give an idea as to location. This is of interest because a postal historian could find numerous covers (sometimes with letters) relating to coal mining in France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom from this period. If this topic grabs your attention, you could pursue mining related items using the knowledge of where the coal fields were situated to help you.

This article just might provide an excellent rabbit hole regarding mining in the St Etienne (Loire) region (resource 4). And, if you want to read about the formation of coal beds, including the one for the Chazotte mine, you can go here (resource 5). This is an illustration of how postal history is dangerous - you can find yourself reading and becoming at least mildly interested in things you never considered before.

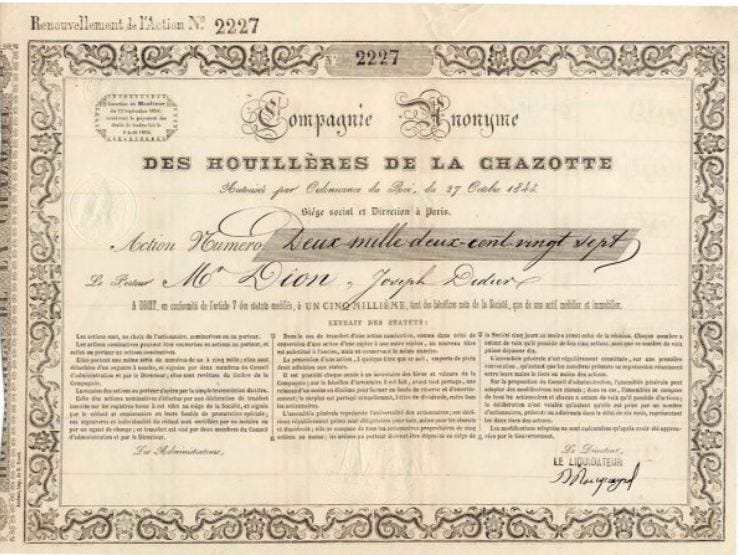

A quick search resulted in finding the following scan from a document from 1843. I do not own this item (nor will I, given the price). A person could own shares of Chazotte mines. I wonder if Evrard's efforts at innovative machinery helped share prices or not?

I place the financial component front and center to remind us of what drove the exploitation of coal fields in the first place. With the event of coal fired engines, the demand increased rapidly. Prior to this coal was used for heating and smelting iron ore. But now, trains, steamships and all sorts of other equipment (including Evrard's inventions) were using coal to provide power.

To close things out, I wanted to point out that it was not just the coal field that was exploited in the mining of coal. This interesting summary regarding the Felling Collier Disaster in 1812 reminds us that mining was (and still is) a dangerous job (resource 6). In this single disaster, ninety-two people died, ages 8 to 65. In fact, the coal communities in Europe are still seeing the effects that the focus on coal created in the present day. This interesting paper by Esposito and Abramson notes in the abstract that:

... former coal-mining regions are substantially poorer, with (at least) 10% smaller per-capita GDP than comparable regions in the same country that did not mine coal. We provide evidence that much of this lag is explained by lower levels of human capital accumulation and ... result from the crystallization of negative attitudes towards education and lower future orientations in these regions. (resource 1)

It's at this point that you and I look at each other and ask - "how did we get here?"

Oh. Yeah. It was that silly piece of paper that carried a letter or business correspondence to a mining engineer in France. Imagine that.

Thank you for joining me in today's journey! This is one of those cases where I did not expect the Postal History Sunday blog to go as far as it ended up going. I hope you enjoyed it, even if we did get a ways "into the weeds."

Have a great remainder of your day and I hope you have a great week to come!

Resources:

1. Esposito, E., Abramson, S.F. The European coal curse. J Econ Growth 26, 77–112 (2021).

2. Blake, W.P., ed. Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, vol V, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1870.

3. Byrne, O., ed. Spon's Dictionary of Engineering: Civil, Mechanical, Military and Navel with Technical Terms, Vol III, E & F.N. Spon, London, 1870.

4. Barau, D, Les sources de l'histoire miniere aux Archives departementales de la Loire, vol 8, 2nd Semester 2008, pp 40-66. Taken from https://journals.openedition.org/dht/633?lang=en on July 10, 2021.

5. Stevenson, J., The Formation of Coal Beds IV. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Jan-Apr 1913, Vol 52, No 208, pp 31-162. https://www.jstor.org/stable/983997

6. The Industrial Revolution, coal mining, and the Felling Colliery Disaster from Letters and the Lamp: Davy, Stephenson, and the Miners' Safety Lamp, site developed as part of the Lancaster University Impact and Knowledge Exchange Award. http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/lettersandthelamp/sections/the-industrial-revolution-coal-mining-and-the-felling-colliery-disaster/ viewed on July 10, 2021