There was a time during the past (almost) five years of Postal History Sunday when I had no trouble keeping track of certain details. I could recall exactly which articles had been published and knew within a few weeks when that occurred. If I wanted to reference something I had written earlier, it wasn’t terribly difficult to do.

That’s actually relatively important to me because I often use my own writings to “re-find” online resources that I haven’t viewed for a while. It’s all part of the give and take that comes with writing a weekly product. I could spend time keeping links to online sources in a special, organized location OR I can write the next week’s Postal History Sunday. I just don’t have time to do both - and no, I don’t want to argue with you about time savings if I just spent the time organizing the resources.

In any event, I have noticed that some little things have slipped that I don’t think I would have allowed a couple of years ago. For example, I have been off in my Postal History Sunday article counter. Last week I listed it as PHS #240, but it was actually #241. And that error has its roots in December when I counted #224 twice. That error has been corrected - as was my typing the wrong PHS # in the email text for THIS Postal History Sunday.

I guess some things slip out of the container we hope will hold them in.

Which got me to thinking. What if this week’s Postal History Sunday talked about wrapper bands that were used to keep contents together as items were sent through the mail?

A wrapper band to hold it in

Postal history artifacts are often referred to as “covers” because we are looking at the envelopes, cover sheets, or bands that were wrapped around the contents being mailed to hold those contents together and protect them. Strange as it might seem to others, postal historians love to study the wrapper and often consider the contents as a secondary attraction. We do this because the wrapper provides us with the clues we need to discover how postal services processed, carried and deliver the mail from one place to another.

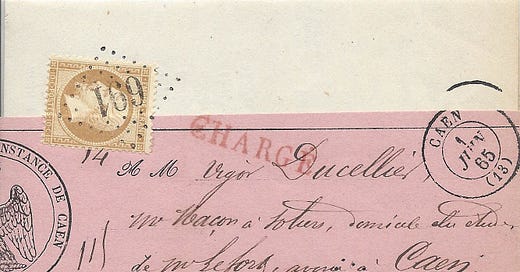

Most cover examples I share are either envelopes or folded letter sheets. But I do have a few wrapper bands, like the pink one shown above.

The contents of this particular piece of mail is a single sheet. That sheet was folded up and then the wrapper band was placed around it. Then, a drop of wax was used to seal the two ends of the band together on the back. Look carefully at the image above and you can see the deformation of the paper where the wax is.

In addition to the wax to seal the ends together, the postage stamps were affixed so that they were attached both to the wrapper band and to the document the band was carrying. This helped prevent the contents from slipping out of the band while it was in transit.

This particular item was carefully opened by the recipient by breaking the wax seal, which means the item is in excellent condition. I can view the contents and then carefully fold things back up so it can appear as it did when it entered the mail at Caen, France.

The content held in this wrapper is a court summons for a person who is listed as a creditor and could claim the distribution of 1195 francs as a result of a court finding against another individual. This individual could come to court with proper paperwork to make the claim, or they could write the court and waive their right to that claim. Since 1195 French francs in 1865 would be roughly equivalent to 13,000 US dollars today, I suspect the recipient opted to make a trip to the courthouse.

The tribunal (or court) that sent this notice was located in Caen, and so was the recipient. The 10 centime postage stamp (buff colored) paid the local postage rate for a simple letter weighing no more than 10 grams (Jan 1, 1863 - Aug 31, 1871). The 20 centime stamp (blue) paid the “lettres chargees” fee (Jul 1, 1854 - Aug 31, 1871).

The same, but different

Our next item seems to be quite similar to the last. This 1864 local letter was mailed from Chambery to Chambery and it also used the registry services. Once again, the contents is an official court document.

Unlike the first item, the news this time wasn’t good news. This official notice from the tribunal in Chambery is a summons for an appearance in court. The letter informs the recipient that they may assign a substitute to appear and that failure to appear would incur a fine.

And this time, we can determine a bit more of the story by looking at some of the postal markings written on the wrapper band.

There is a small notation on the front of the cover at the lower right that reads "au dos," which gives the instruction to look "on the back." And, so, our curiosity peaked, we look on the verso to see what is there that needs to be known.

On the back is the word "Inconnu," which indicates that the individual is "unknown." In other words, this person could not be found by the postal service in Chambery and there were no instructions for forwarding the mail. So, this item was returned to the sender (the tribunal/court) and the combination of "au dos" on the front and "inconnu" on the back gave the tribunal a reason for that return.

With the addressee not located, there was most likely a fine levied. Whether that fine was ever paid probably depended on whether the recipient was ever located again.

Bands for printed matter mail

For the most part, wrapper bands were more typical for printed matter mail than for letter mail. This makes sense since printed matter was supposed to be accessible to postal clerks so they could be sure no additional personal correspondence was included with the printed matter. Letter mail was normally fully enclosed and sealed to protect the contents.

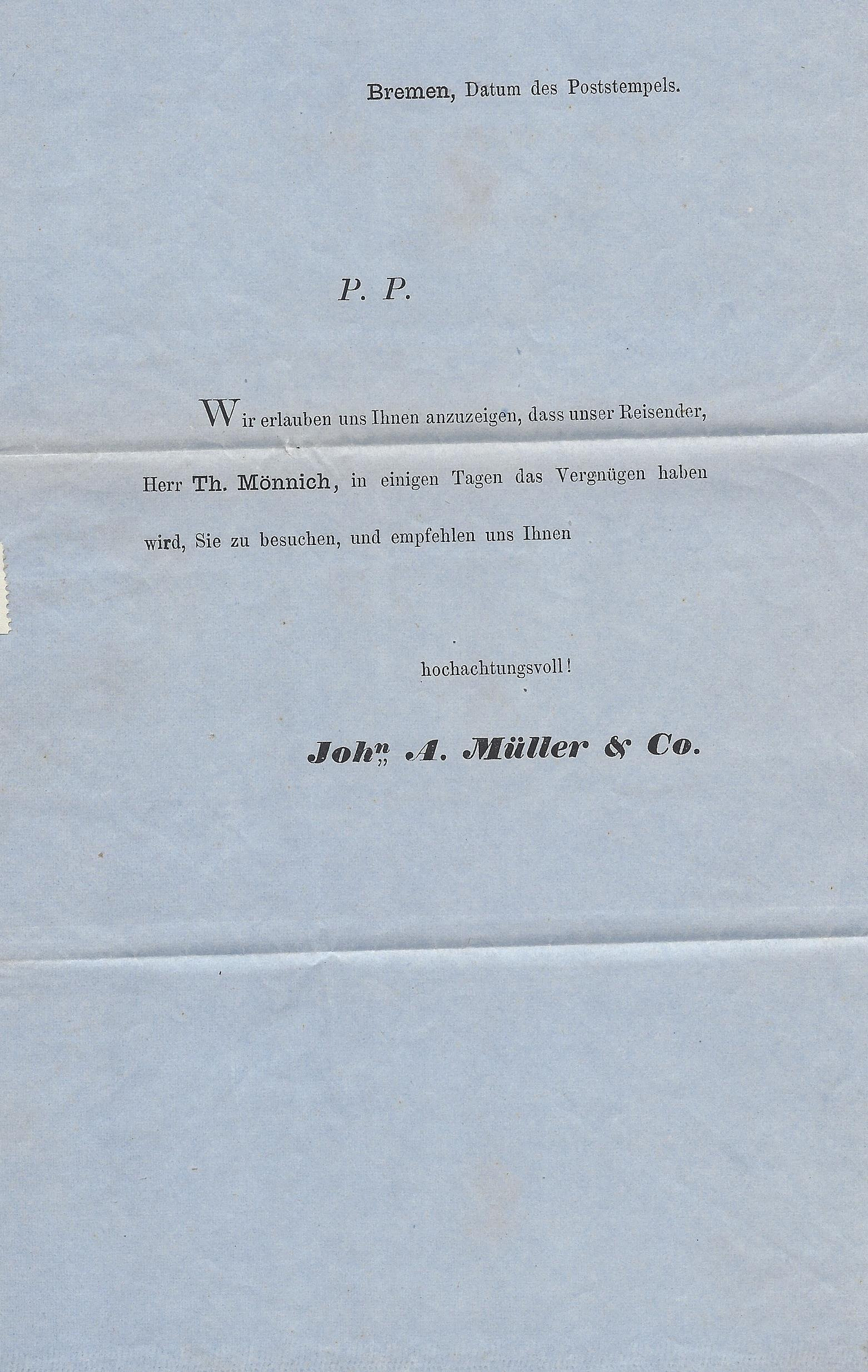

Shown above is a piece of printed matter - an adverstising flyer - that was mailed via the Thurn & Taxis post from Bremen to Bückeburg in the 1860s. The postage rate was 1/3 siblergroschen for a a piece of printed matter weighing no more than one loth (rate began Sep 1, 1861).

At the time this mail item was sent, Germany was still broken into many separate governing states - though this was changing during the 1860s. Many of these German States used the Thurn & Taxis mail system, including Schaumburg - Lippe, where Bückeburg was located (west of the city of Hannover).

The city of Bremen actually hosted multiple post offices, including Thurn & Taxis. So, if a person wanted to send a letter to a place like Bückeburg, they could use the post office that served them rather than going to the Bremen post.

Just imagine if it worked that way in the present day. If you wanted to send a letter to India but you lived in Paris, you could go to the India post office located there and simply pay their postal service to handle it all. While the logistics for global mail is a different scale than mail inside the German States during the 19th century, I think it serves to help you understand a little better what was going on.

The contents for this piece of printed matter is actually a very simple notice that a representative for Joh(n) A Müller & Company would be visiting Bückeburg.

We would like to inform you that our traveller, Mr. Monnich, will have the pleasure of visiting you in a few days and recommend ourselves to you. Respectfully!

Johann Müller established a shipping and warehousing business in 1821 that specialized in moving goods up and down the Weser River. By 1835, the company was well established at the port of Brakerhafen (Brakerhaven), down river from Bremen city.

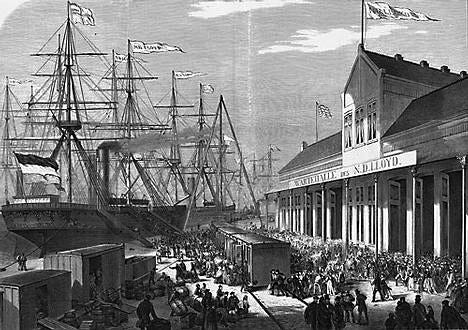

Postal historians are aware of Bremerhaven (established 1827) as it was the port where mail ships would arrive and depart for the North German Lloyd steamship company. The NGL steamers carried mail between the United States and Bremen beginning in 1857. But we often gloss over the fact that the port of Bremerhaven is actually some distance from the city of Bremen (64 km).

Prior to 1834, when Müller started his business, the fastest method of travel between Bremen and ports that could hold ocean-going vessels like Bremenhaven and Brakehaven (first mention as a port 1756) was by river barges often pushed by paddle steamers. This method of conveyance took two to three days. A highway was completed in 1834 that allowed horse drawn carts to travel, taking about seven hours to cover the distance to Bremerhaven and Geestemünde (est 1845). While I don’t find the development of a highway to Brakehaven, I assume there was similar development there.

It is likely that Müller provided both river barge transport and cart services to Brakehafen. Remember, Muller started his business in 1821, before either Bremerhaven or Geestemünde were available for shipping. His business’s strong connections to Brakehaven made his business vulnerable to competitors shipping goods to the new ports on the Weser. So, the establishment of rail from Bremen to Bremerhaven and Geestemünde in 1862 was a difficult blow.

But, before we start to feel sad for Müller, a quick search shows us that J. Müller Company has celebrated two hundred years in business and that the port of Brakehaven has undergone multiple significant upgrades over the years. Possibly one of the most significant was when J. Müller & Co worked to connect Brakehaven to a railway in 1873. Once completed, Brakehaen (and Müller) was on an equal footing with the other ports.

But, they still had to suvive as a business for a decade without a direct rail connection. Perhaps it was thanks to Mr. Monnich, who did a fine job promoting the business to customers in Bückeburg during the 1860s?

Why three ports competing on the Weser?

Please allow me to remind you that Germany was split into multiple states at the time these ports were being developed. Oldenburg, Hannover and Bremen all had access to the Weser River and the Weser emptied out into the North Sea. Access the the Sea (and hence the Altantic Ocean) was important for any European state to have advantages in trade. Thus, each state invested in the development of port services that were under their control.

The state of Hannover pushed to develop Geestemünde, Oldenburg worked to improve Brakehaven and Bremen, of course, had Bremerhaven. To make matters even more interesting, Hamburg was developing Cuxhaven at the mouth of the Elbe River - just to the northeast of the Weser.

And now I think you can understand how the competition to get rapid transport to each of these ports was important for the development of the ports themselves.

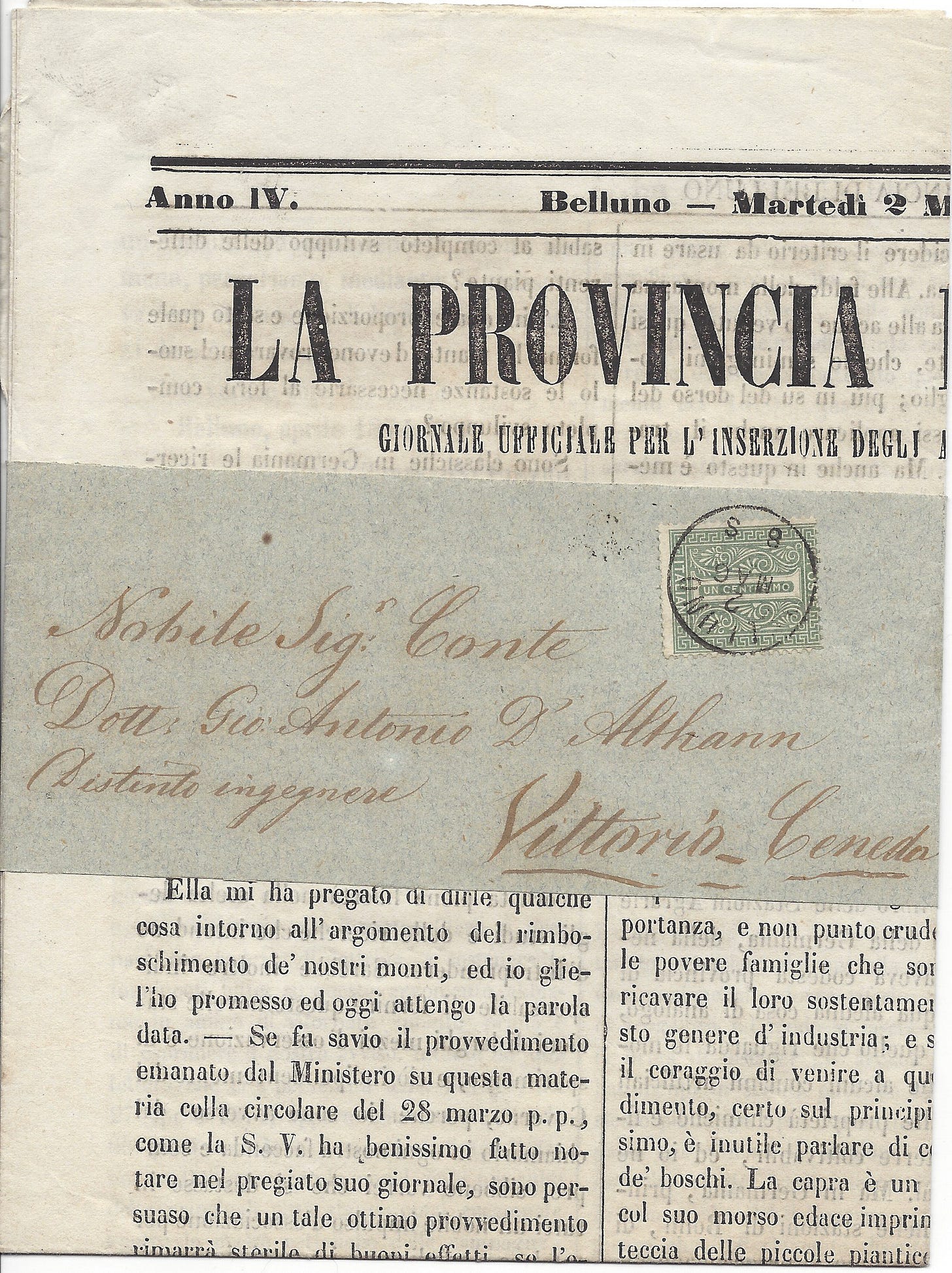

Keeping newspapers intact

A very common type of printed matter were periodicals and newspapers. The image above illustrates how a wrapper band was used to keep a newspaper together for mailing. This item looks like the recipient never opened this particular issue of La Provincia di Belluno (dated March 2, 1871). But that makes it all the better for us to see how the wrapper bands did their job.

A paper wrapper band served as a surface for the mailing address and postage. The band also kept the newspaper together and prevented it from inconveniently opening up while it was in transit through the mail services. In this case, the band is not attached to the newspaper at all.

A one centesimi postage stamp provided evidence that the postage was paid. The basic bulk newspaper rate was 1 centesimi per 40 grams of weight (Jan 1, 1863 - 1889). However, there was a concessionary rate for newspapers available for mailers who provided pre-sorted bulk mailings (by destination and route). Further discounts could be possible based on frequency of mailing. Therefore it is possible that the stamp does not represent the actual amount of postage paid for this particular newspaper.

We could speculate as to the reasons why this particular artifact remains in this condition nearly 150 years after publication and mailing. Perhaps this item arrived while the recipient was away and they never caught up on the backlog of papers when they got home. I find it hard to believe that someone would read the paper and then painstakingly fold it up and put it back in the wrapper.

Speaking of which, I hope I managed to keep all of today’s Postal History Sunday details inside the wrapper that is this article! If I didn’t, please drop me a comment and let me know what I missed!

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.