Time has a way of making fools of all of us. It can force us to move on from things we enjoy before we are ready and sometimes it pushes us to accept less than optimal responses to a problem.

I, in particular, have a tendency to feel a bit foolish when Saturday comes along and I have yet to complete the week’s Postal History Sunday. It’s on that day of the week where I often realize that my well-meaning, but unrealistic, plan to get ahead of the writing game has fallen short yet again.

So, in honor of the things we do when time pushes us to be foolish, this week’s entry is going to look at a special service for mail that encouraged those with time management issues to depart with some of their money.

And with that, I’m going to encourage you to push your troubles aside, grab a favorite beverage and settle into your comfortable reading chair. Let me assure you that it’s perfectly okay to foolishly spend a little time reading when you’ve got your fuzzy slippers on! So let’s see if we can all learn something new today!

Two Examples with Two Shillings

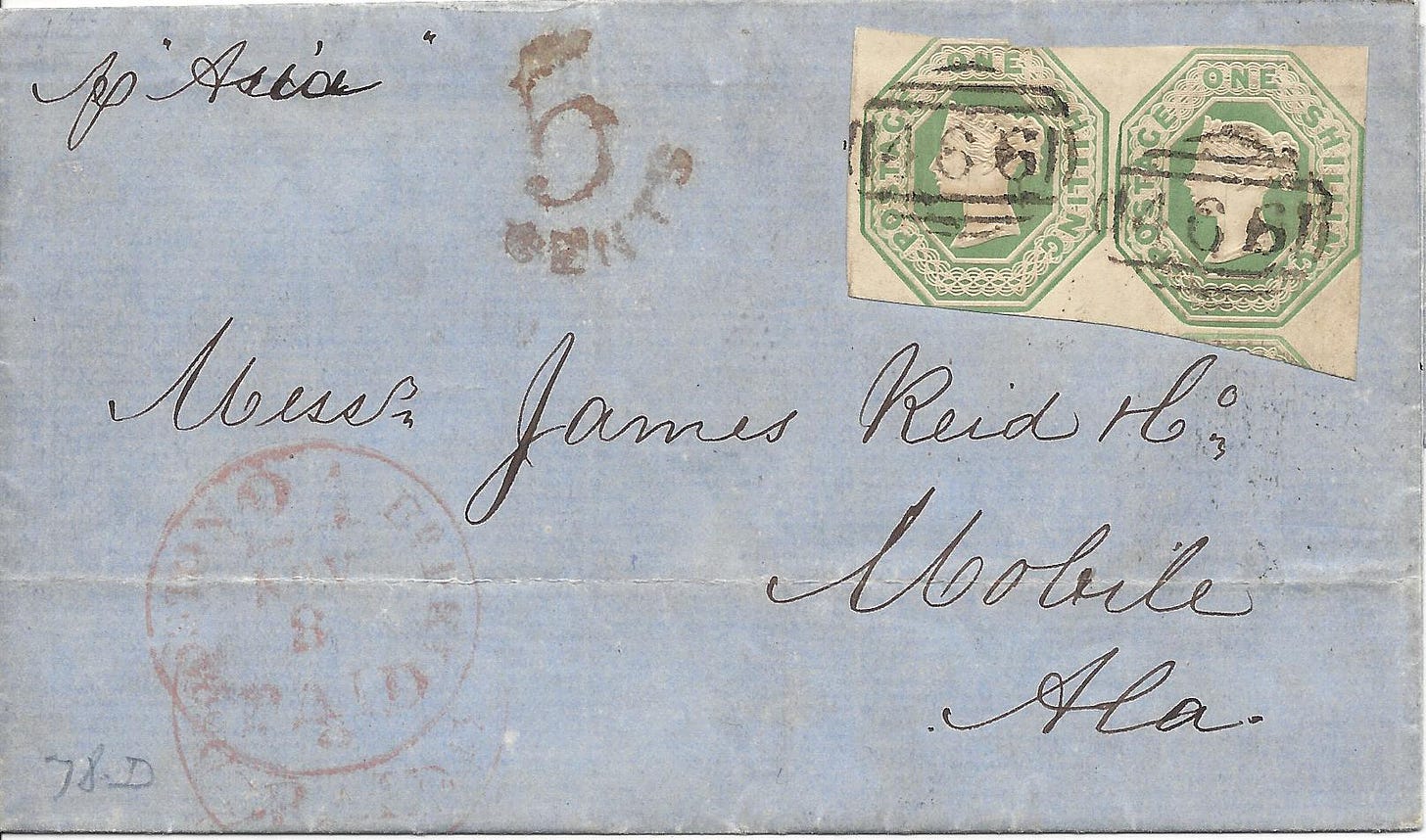

This week, I am going to start by showing you two covers that are a bit different from the most common type of letter mail we would see from the UK to the US in the 1850s and 60s. In both cases there are postage stamps that represent two shillings of postage paid to get the letter from Liverpool to its destination in the United States.

The first such letter is shown above. It was mailed on October 27, 1855 in Liverpool. It traveled across the Atlantic Ocean on the Cunard Line’s steamship named Asia, arriving in Boston on November 8. From Boston, it went to Mobile, Alabama, where a representative from James Reid & Co picked this letter up at the Mobile Post Office.

Unfortunately, we have no postmarks or dockets on the cover to help us figure out when it was received or how it might have gotten there from Boston. But, luckily, that’s not the focus of today’s story.

And here’s the second letter which was also mailed in Liverpool, but in 1858. Once again, there are two stamps showing that two shillings in postage were paid. This letter was written and mailed on May 29, 1858. It sailed with the Cunard Line’s Asia, arriving in New York on June 10.

This letter is addressed to Samuel Thompson’s Nephew, a shipping and mercantile company located at 275 Pearl Street in New York City. Since there is a street address, we can make the educated guess that the letter was taken there by a letter carrier who expected to be paid a penny for the delivery service. But, there are no postal markings on the cover to confirm that.

At this point, you are probably wondering what the big deal is - and that’s exactly what I was hoping you would be wondering.

Because that’s what I wanted to write about today.

A Typical Simple Letter

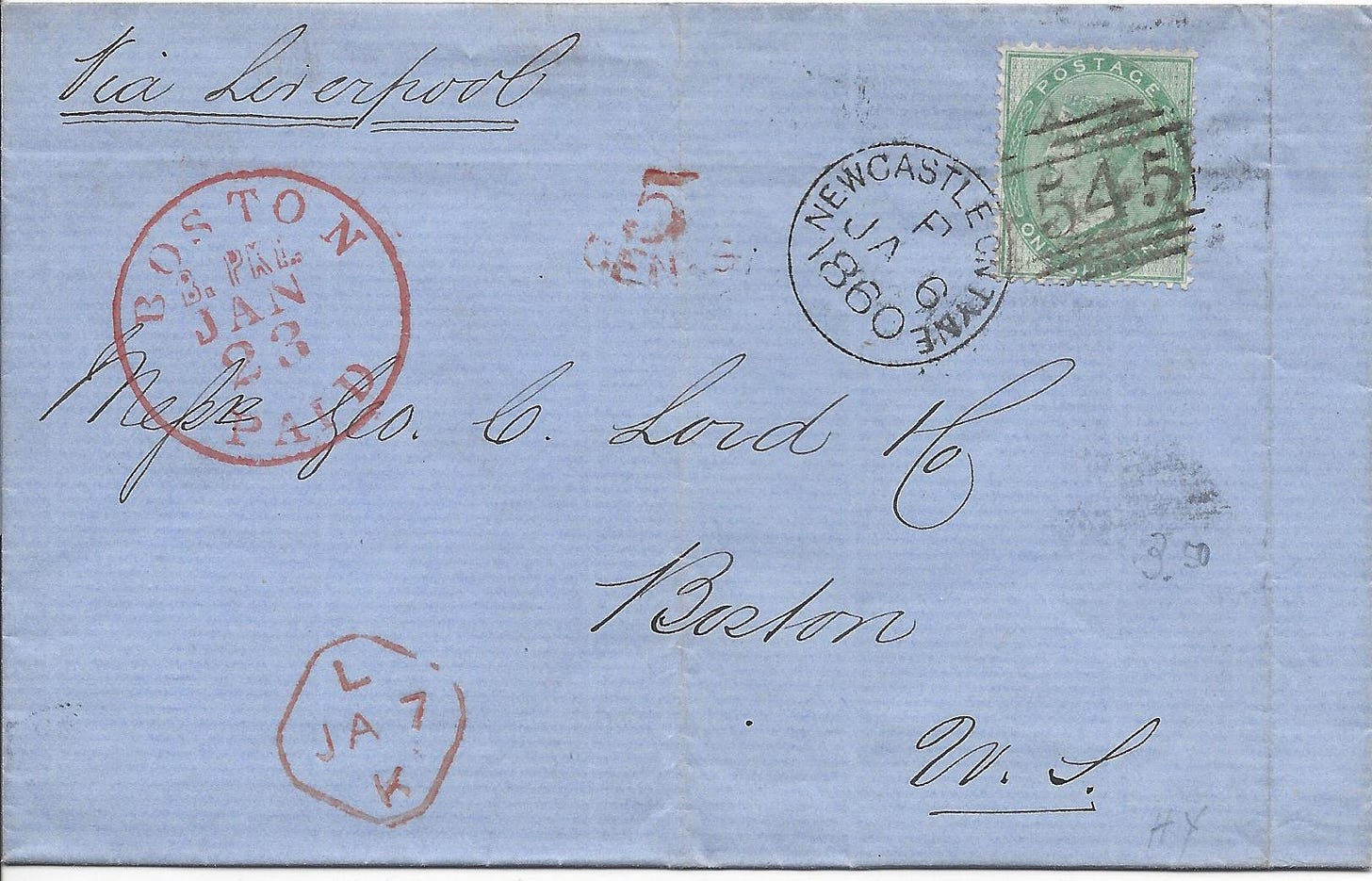

Let me start by showing you a common simple letter that would have been mailed during the period from 1849 through 1867. The cost for a simple letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce was one shilling (the equivalent of 24 US cents). So, most letters would look like the one shown above - with only a single 1-shilling stamp paying postage.

This folded letter started at Newcastle-on-Tyne and was mailed on January 6, 1860. It traveled to Liverpool where it departed on another Cunard Line ship (Africa) to cross the Atlantic. It arrived in Boston on January 23 and was picked up by a representative for George C Lord & Co.

So, what’s the difference here?

If you noticed that the first two originated IN Liverpool and the third did not, you would be very close to the point. But, it has nothing to do with a different postage rate and everything to do with a special service in Liverpool for those who were willing to part with an extra shilling in an effort to buy time.

The Floating Receiving House at George’s Landing Stage

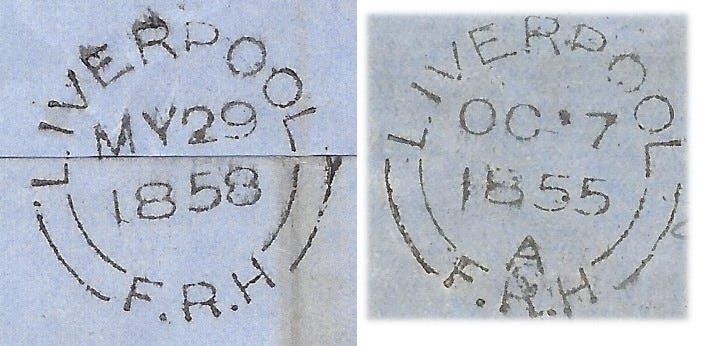

The answer to our question is actually located on the backs of both of our first two folded letters. Each of them bears a postmark that reads “Liverpool F.R.H.” around the rim of the marking. Liverpool letters from 1847 to 1864 that have this marking were accepted by clerks at the Floating Receiving House (FRH) at George’s Dock, where the Cunard Line steamers would depart with mail to the United States.

The Floating Receiving House existed so people could get their mail onto the ship after the normal closing time. In fact, they could post a letter very close to a ship’s departure time. The cost for this “foolishness” was an additional shilling, which is typically represented by a 1-shilling postage stamp on covers that used this service.

And now it makes sense that the third letter did NOT use this service since it did not originate in Liverpool. I don’t think a person at Newcastle-on-Tyne would find it at all convenient or useful to hustle to the docks in Liverpool to get a letter onto a ship after the mail closing time. It’s a small matter of a 178-mile trip to get there. And I think it would end up costing them more than a shilling.

It appears that the second letter was written on the landing stage. The first line reads “We have just time before the last bag closes this morning to say that the “Lady Franklin” was off Holyhead at 8:15 last evening…”

In other words, this person was writing about another ship that was on its way to the United States that had apparently already left Liverpool and was observed off the coast of Holyhead the evening before.

The addressee, Samuel Thompson’s Nephew Company, served as agents for over a dozen sailing vessels, including the Lady Franklin. This ship was often used to take advantage of the “immigration industry,” carrying between 400 and 500 passengers each trip. A typical East to West crossing by this steamship was around two weeks, not much slower than the Cunard steamships that carried the mail.

Even so, this person felt it was important to send, as quickly as possible, a letter giving this shipping intelligence to the agents in New York City. It certainly wouldn’t have helped to wait until the next mail departure a few days later because the letter certainly would not have arrived before the Lady Franklin - assuming all went well.

As it stands, I suspect you might be wondering how important this letter was in any case? It was going to take twelve days for the letter to get to its destination and be read. The other ship had a half day head start and would likely arrive a day or so after the letter.

That’s when you need to remind yourself that there wasn’t going to be a faster way to communicate. The Lady Franklin wasn’t going to be able to “radio their location” to people in New York. There would be no phone call.

It was reports like these that helped shipping agents track the progress of their shipments. They would know, based on this information, to look for that ship’s arrival. Or, if it failed to arrive, they would be aware that something was wrong that might need to be addressed.

Closing the Mail

“…one of the most remarkable sights in London - a sight which may be witnessed every evening for about ten minutes before the long and the short hands of the big clock-face at the Post-office, St. Martin’s-le-Grand, form a vertical line exactly bisecting the arc between the VI. and the XII… the broad steps before the chief office are occupied by a throng of persons all struggilng towards the great open mouth of the box which receives letters for despatch…” Catching the Post by Thomas Archer in Cassell’s Family Magazine 1884.

Take a moment and use your imagination to transport yourself to a time where you could not pick up a phone and call (or text). A time where conversations separated by distance required more than moments to get a reply.

In the 1850s, knowing the scheduled closing time for mail at the post office made a difference if you were anxious to get the quickest possible response. This was especially true for those who wished to communicate with someone across the Atlantic Ocean. Each of the letters shown above required 12 to 17 days to cross “the Pond.” Even if the recipient sat down and immediately wrote a response, a person would expect to wait about a month for a reply if all went well.

Post offices maintained closing times for the mail based on the scheduled transportation that was to carry the post. The mode of carriage might have been a mail coach, or a mail car on a train, or a steamship crossing the Atlantic. Regardless, there was always a point when a letter would be too late to be loaded up and sent on its way.

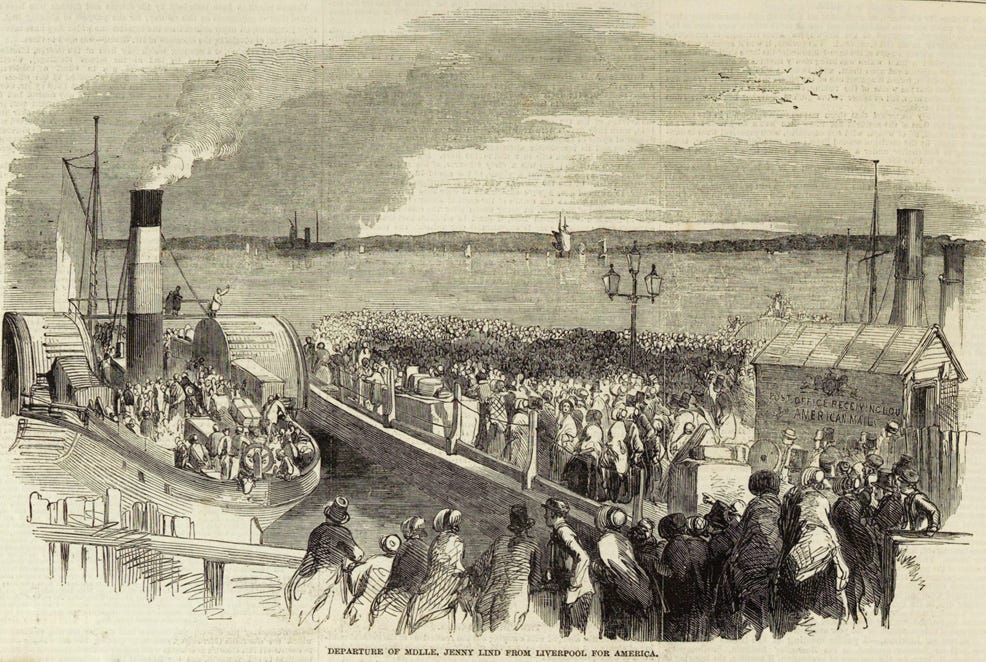

Post offices set closing times for the mail that would provide the mail clerks time to process and prepare the letters, newspapers and packages. But, people being people, the times just prior to those closing times often saw the greatest traffic. Boys carrying the mail for each small company in the area would rush to deposit the basket or bag of letters to be sent out that day. And sometimes, they would be too late.

The British Post recognized an opportunity to accept late mail (up to a point), but they required extra postage to pay for this late processing.

For example, the letter shown above was a heavy letter to France that required 6 pence in postage - but there are 7 pence in postage stamps. That extra penny paid a late fee so this letter would still be processed to go out with the latest transport to France. The late fee is confirmed by the boxed “L1” marking in red on the cover.

The two letters I started with today were much more expensive to send. Each required an extra shilling in postage (a shilling = 12 pence), making it an extreme example of a person’s willingness to pay a late fee in order to get a letter on its way after a mail closing time. For comparison, if we use an inflation calculator it would be the same as spending almost 7 British pounds (about $9) in the present day.

We just have to remember that a delay would have rendered the second communication useless. So maybe it actually was worth it.

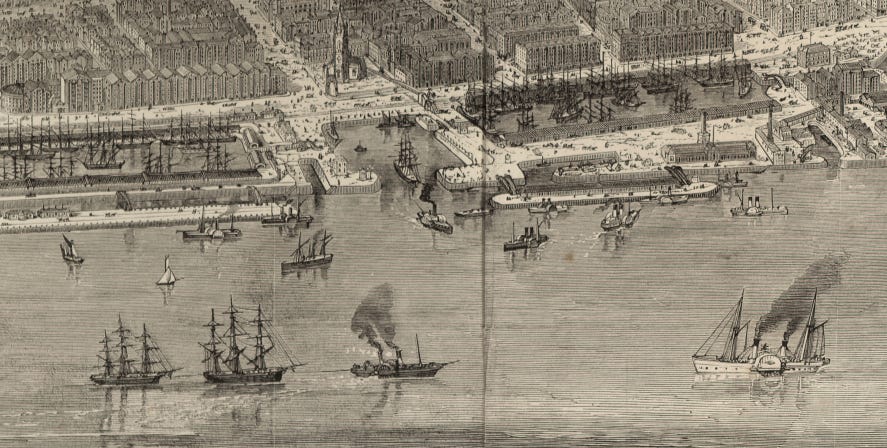

The Floating Landing Stages in Liverpool

The city of Liverpool was, at the time these letters were sent, an important port for the United Kingdom. It was also an important port for the carriage of the mail between the US and the UK. The Cunard Line, with their contract to carry mail for the British and the Inman Line, with an American contract, both sailed from this port. They would make one more stop at Queenstown, Ireland, on their way to New York or Boston.

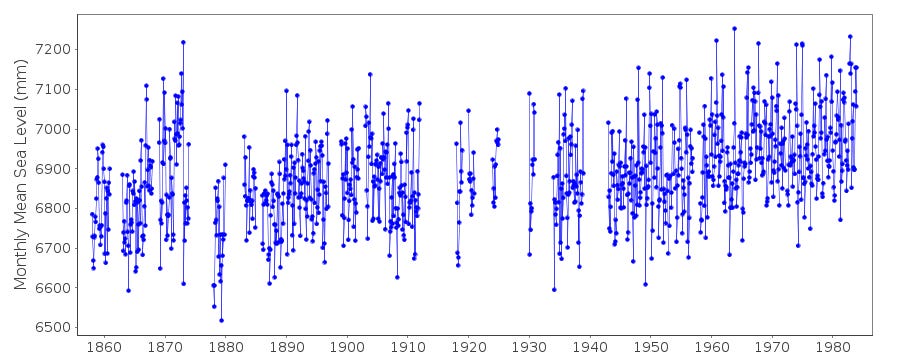

The port itself was located the River Mersey widened before it enters the Irish Sea. And, like many locations where shipping was prominent, it wasn’t without challenges. In this case, there was a need to address changing water depths. Liverpool has a wide range of tide levels.

If you consider this problem from the perspective of a ship that is docked for loading and unloading, you can see the problem tides might cause. As the tides come in and go out, a ship would rise and fall with the depth of the water. A stationary dock, on the other hand, did not change its height with the tide.

On May 31, 1847, a floating stage was placed off of the George’s Pier that would serve two purposes. The stage could be further out in deeper water for bigger ships - which means passengers and cargo wouldn’t have to be placed on a smaller ship to bring them to land. And, loading and unloading would not be interrupted by changing tides.

At over 500 feet long and over 80 feet wide, George’s Landing Stage was the largest structure of its kind at the time. It would allow ships to moor without fear of grounding and it could allow for continuous loading and unloading to and from the ships.

A clerk at the Liverpool Post Office proposed the idea of a letter receiving house could be placed on George’s Landing Stage.* This would allow the poor souls in Liverpool who had missed the closing time for the American mails to drop off mail at the docks practically up to the point of the ship’s departure.

Of course, this service would not come without a cost. Perhaps an extra shilling would be enough to make it worthwhile to maintain the receiving house and pay the clerks staffing it? There may have been some squawking about the price, but the existence of a fair number of covers with F.R.H. markings tell us it wasn’t so much that business people would not use it.

A small building was placed on the floating landing stage beginning in August of 1849 and continued to be in use until the mid 1860s. I have read in some places that this building was on wheels so it could be moved to different docking locations on the stage. As a farmer, this makes sense because we have portable buildings for various purposes. But, I have not been able to confirm whether this was put in place for the Floating Receiving House on George’s Floating Stage.

*Tweed, J: The Liverpool Floating Landing Stage Receiving House – The 6d Late Fee, TPO Journal Vol 68 No. 1 (Spring 2014), TPO & Seapost Society, 2014

The Liverpool Receiving House saw sufficient use up until 1859, when the cost was reduced to 6 pence (half the original cost) in response to declining use. An improved railway system made it possible for letters to take the Irish mail route via Holyhead and Kingstown, and a night mail train became an option. Since the Cunard and Inman steamers stopped at Queenstown, Ireland, letters could be forwarded there to catch the same ship that had departed Liverpool - without paying an extra shilling (or 6 pence).

Faster mail options without paying more money? Of course people gladly took advantage of that possibility! As a result, the extra fee to use the Floating Receiving House was discontinued in 1864.

George’s Landing Stage was only the first floating landing stage on the Mersey. A second was in place by 1860 off of Prince’s Dock. Eventually, these two would be come one long landing stage that was sufficiently large to allow even the larger ocean-going vessels to moor.

The postcard image I showed earlier is an image from 1905. It illustrates this larger, single, landing stage. Other similar images from that time period also show a Landing Stage Post Office which operated as a regular post office with its own mail closing times. And, of course, they implemented a penny late fee for those who just didn’t get there in time to drop off their mail.

Because time makes fools of us all.

Would you like to learn more?

There is a census of covers that show the Floating Receiving House markings which is offered here by the TPO & Seapost Society. As of 2021, this census records one hundred covers with the 1 shilling FRH late fee. The second cover I shared today is in that listing, while the second one is not.

Also, PHS #232 features a letter to Liverpool. So, if that theme interests you, go give that one a visit!

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I learned quite a bit from this - thank you! I have a number of FRH covers in my collection, and I’ll have to check the census (didn’t know it existed!)

A couple of years ago I handled a rare embossed FRH cover for a NY auction house. The cancellations were all in red, which is quite unusual. It sold for $8,000.

Some incredible illustrations this Sunday! The history of the floating landing stages was very interesting. Thanks Rob! Enjoy the warming weather!