After a long day of picking up feed for the poultry, cleaning up a couple of vegetable plots and then planting garlic, I sat down to finish this week’s article. I found myself staring at the draft of my most recent Postal History Sunday selection for this week and realizing it wasn’t as close to completion as I hoped it was. Now what?

The solution was to pick an article from well over two years ago and treat that like a draft. Some might consider this cheating, I suppose, but that’s because they have no idea how much effort actually goes into these rewrites. And, I am guessing the number of people that will even remember reading this in its prior form could be counted on one hand (and that’s if I count myself twice!).

Now, it is time for you to let those troubles go as if the much-needed rain in Iowa were washing them away. Pour yourself a favorite beverage and maybe get something to snack on while you read because…

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

Getting to know the Regular Ducks

I remember playing the game called Duck, Duck, Goose (or Duck, Duck, Grey Duck if you live in Minnesota) when I was in elementary school. This group game was a good way to allow young people to exert a little energy even if they were trapped indoors by the weather. The participants sat in a circle, facing the center, while a single individual was chosen to walk around the outside of that circle. As this person walked, they would touch each person in the circle as they went by and they could opt to say “duck” or “goose / grey duck” as they did so.

If you were sitting in the circle and this person tapped you and said “duck,” you would remain seated. However, the fun (and the laughter) would begin when someone would be tapped and the word “goose (or grey duck)” was spoken. That person would get up and try to chase the person who tapped them, running around the circle until they tagged them or that person managed to sit in the spot that was now open in the circle.

Ok, that's enough of that. The point I am making is that the goose / grey duck is different than the ducks. I like to think of the simple letter as the "duck" of postal history. The vast majority of surviving postal artifacts are, in fact, simple letters like this one:

Other than the junk mail most of us are quite familiar with, we might have the most familiarity with letter mail. Junk mail is typically referenced by postal historians as printed matter or reduced rate mail. Unsurprisingly, that sort of mail is harder for a postal historian to find because it is often considered to be "junk" and is thrown away. Letter mail, on the other hand, is more likely to be personal in nature - whether it serves as a business record or is part of a personal correspondence. That makes the chances that a postal historian will encounter old letter mail pieces much higher.

A simple letter is the most common sort of letter mail. To put it - simply, of course - a simple letter requires a single rate of postage for that letter to travel from its point of origin to its destination. This typically means the weight of the letter is below a certain limit.

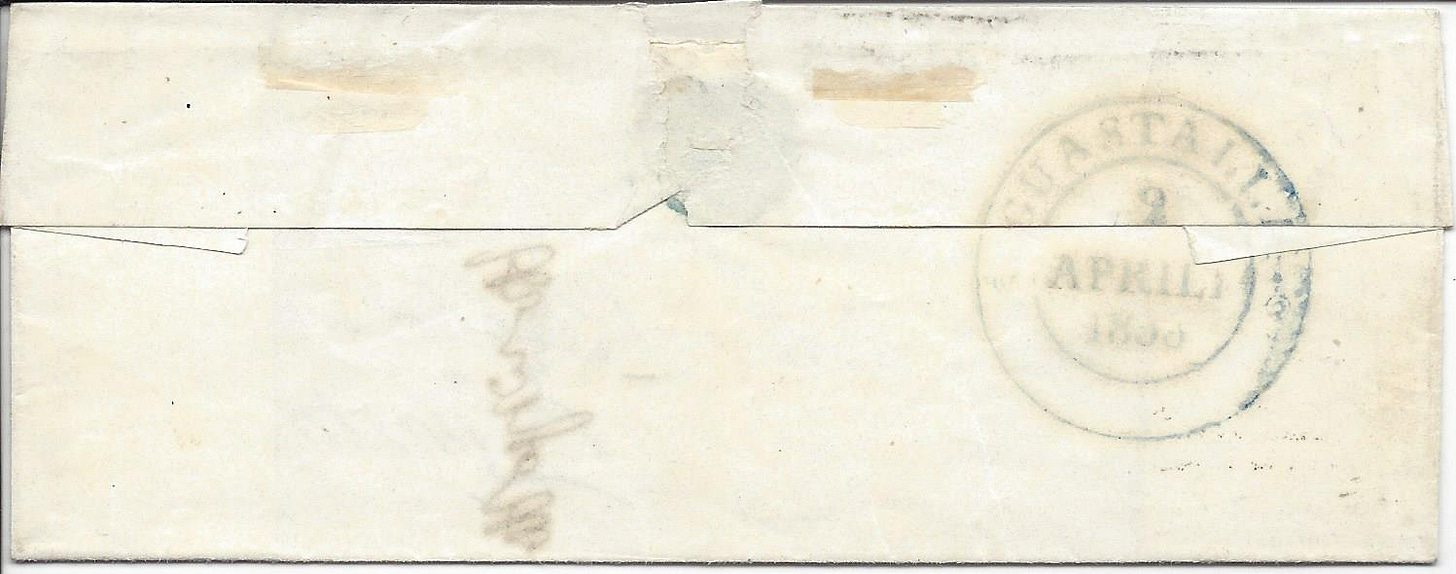

Shown above is an example of a simple letter that traveled in the mails internal to the Duchy of Modena, which was ruled by a member of the Habsburg line. The postmark at top right tells us it entered the mail at Modena (the city) on Apr 1, 1853 and was sent to Guastalla, about 56 km to the northwest. The back has a marking from Guastalla that shows it was received at the post office there on the same day.

The green postage stamp has a 5 centesimi value, which was the correct postage for a simple letter in Modena that traveled no more than 10 meilen (75 km). Letters qualified as a simple letter if they weighed no more than 8.75 grams. This postage rate became effective on Sep 4, 1852 and remained in effect until mid-1859, when Modena was going through the process of unifying with Sardinia and other Italian states to create the Kingdom of Italy.

A Duck that traveled further

Modena had a relatively complex postal rate system. Not only was there a weight component, there was also a distance component to calculate how much was required to send a letter from here to there. The first example was a simple letter for the shortest distance. This next cover illustrates a simple letter for the longest distance for a letter within Modena’s borders.

Modena was not terribly large, so most internal mail would not travel more than 75 km (10 meilen). However, there were locations within the duchy that were further apart. A simple letter that traveled these greater distances had a higher postage rate - 10 centesimi per 8.75 grams (rather than 5 ctm for the shorter distance).

The cover shown above was sent from Massa-Carrara on April 10, 1854, to the city of Modena, arriving two days later according to the postmark on the back. Massa-Carrara was located near the shores of the Mediterranean and was about as far away from the city of Modena as you could get (about 150 km) and still be in the Duchy of Modena.

I recognize that most of us do not travel around with a mental image of 1850s Italy in our heads, so I thought you might like a visual to help you see what is going on here. Modena is the purple region just above Tuscany (yellow) and between Parma (to the west) and Romagna (to the east).

At this point, we have identified two regular “ducks” for simple letters mailed internally in the Duchy of Modena during the 1850s. I find it very useful to identify the "ducks" in a new postal history subject area so I can learn what would be considered normal, or common, characteristics for mail of the time. Once I know what a duck looks like, I have a chance to be ready for any "goose" that might come along - whether it is something uncommon or something that has been altered and is not what it seems to be.

Modanese Ducks for the Austro-Italian League

Austria, along with the Italian states of Tuscany, Parma, Modena, Lombardy, Venetia, and the Papal State agreed to regulations for mail exchange between all participants. The agreement was revolutionary in that the participants did not split the postage that was collected. For example, if Modena collected 15 centesimi for a letter (like the one shown below), they did not have to pass any funds to the destination member state. To be part of the agreement, members had to issue postage stamps and encourage prepayment of postage for mail.

This letter was sent from the city of Modena in 1855 to Bologna. Bologna was located in Romagna, which was then one of the Papal States. The distance between the two locations was only 43 km, so this cover qualified for the shortest distance category for letter mail in the Italo-Austrian League. The cost in Modena for such a letter was 15 centesimi for a letter weighing no more than 17.5 grams.

Below is a table that summarizes how postage was calculated for each of the participating postal systems. These rates apply to each of the covers I will be showing from this point.

This table identifies for us three other types of “ducks” for the Duchy of Modena. We’ve just shown the first duck (a simple letter sent the shortest distance). So there must be two other ducks we need to see - one for each of the other two distances.

Oh look! Here’s one now!

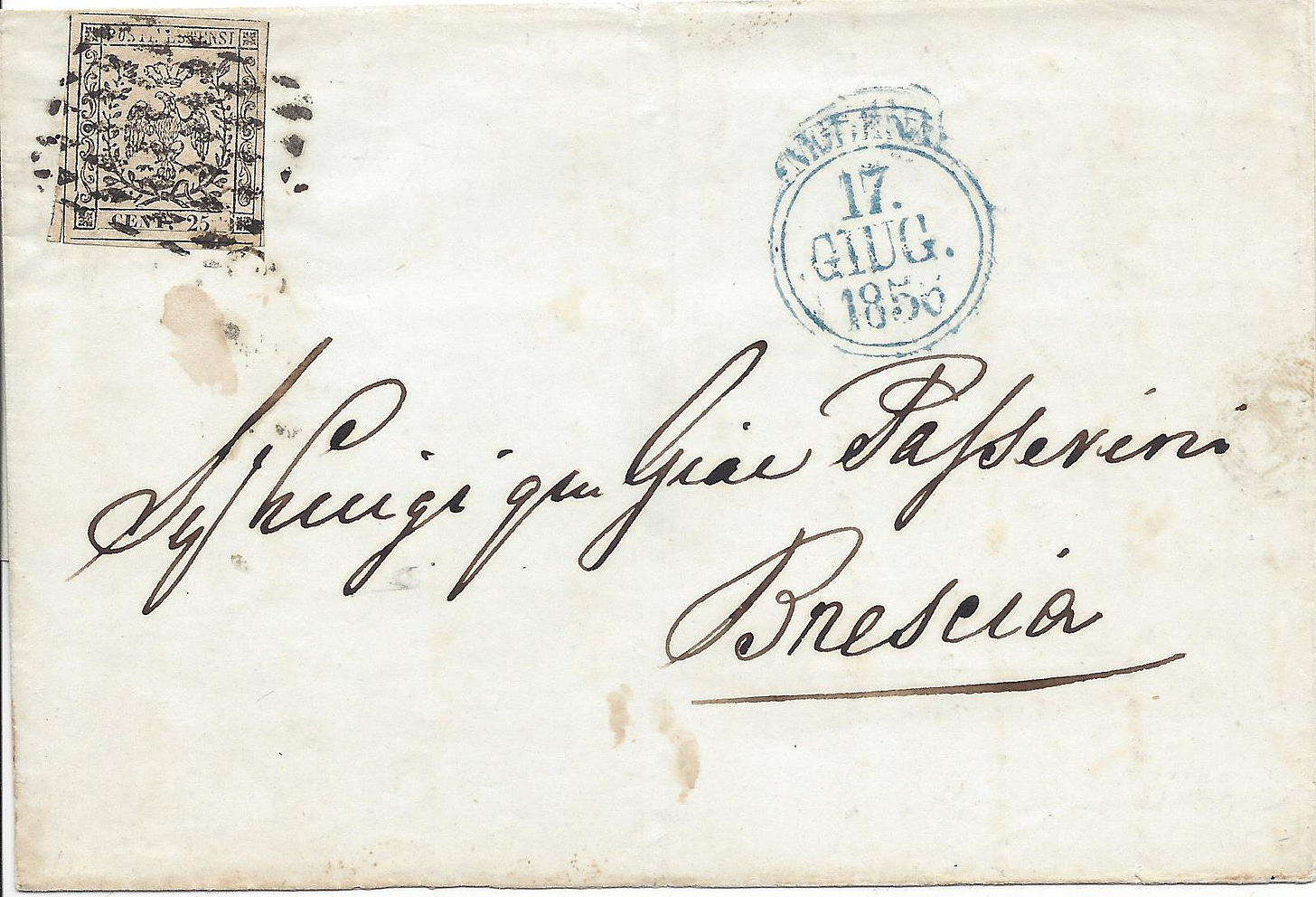

This particular piece of mail bears a 25 centesimi postage stamp at the top right and a postmark in Modena dated June 17, 1856. The letter arrived in Brescia one day later according to the postmark on the back. The distance between Modena and Brescia is right around 150 km, which is approximately 20 meilen. Apparently, the postal tables of the time listed the distance between these cities as falling within the second distance (10 to 20 meilen).

Brescia was in Lombardy, which was part of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia at the time this letter was received.

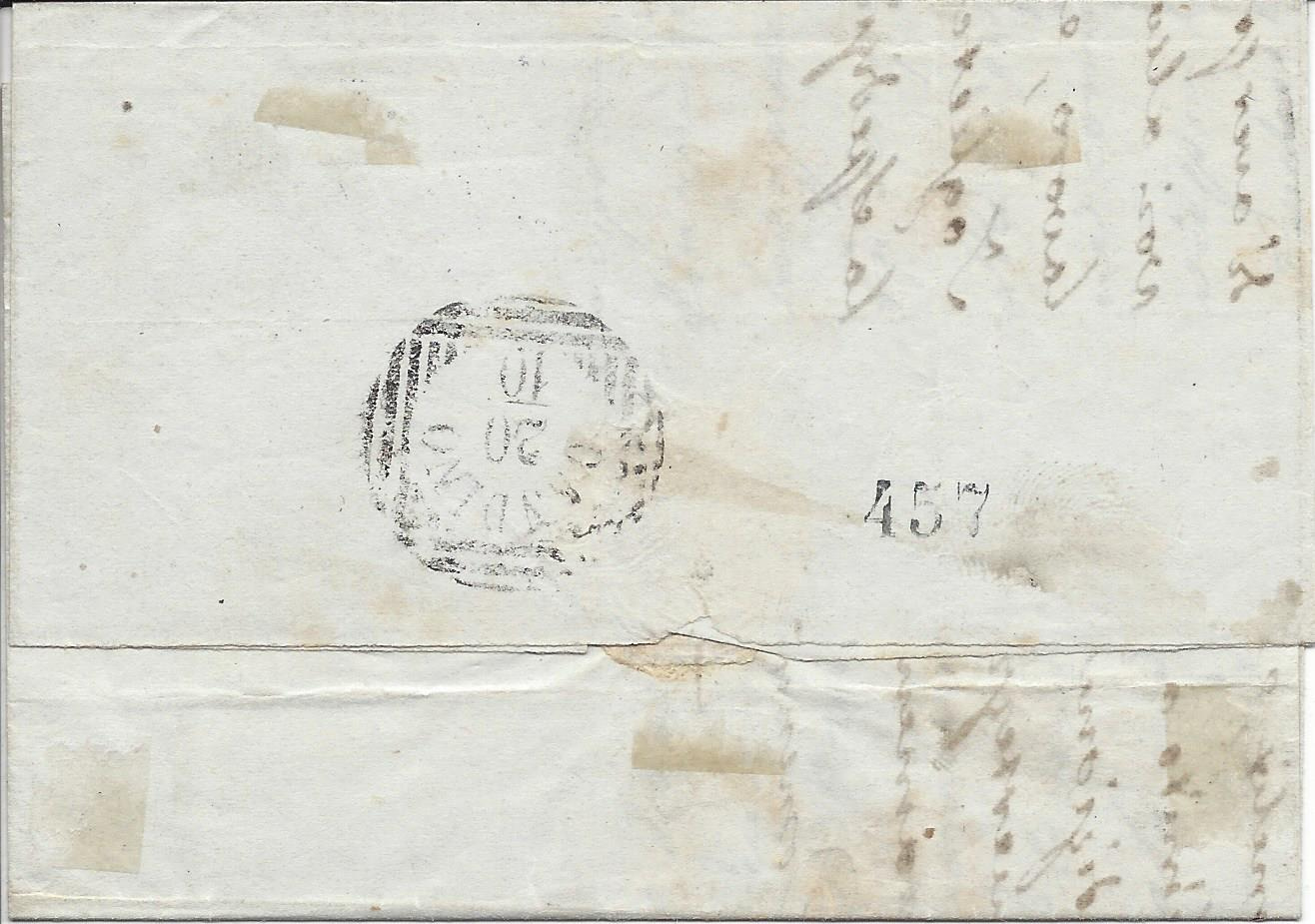

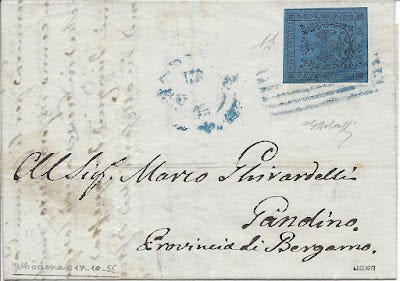

And our last "duck" for this series is shown above - a letter from Modena to Gandino in the Province of Bergamo (which was in Lombardy). Gandino is further north than Brescia, so it makes sense that this letter had to travel further than the last one, exceeding 20 meilen. This qualifies it for the longest distance and the higher 40 centesimi rate.

This folded letter is dated October 17, 1855 and the weak postmark on the front of the cover looks like it could either be Oct 17 or Oct 18. Happily, the receiving postmark on the back is much easier to read.

The letter arrived at the post office in Gandino on October 20, two or three days later. It would be tempting to say the postmark on the front was Oct 18, just to keep the delivery time to two days - but there might be a reason that this letter was slower to get to its destination.

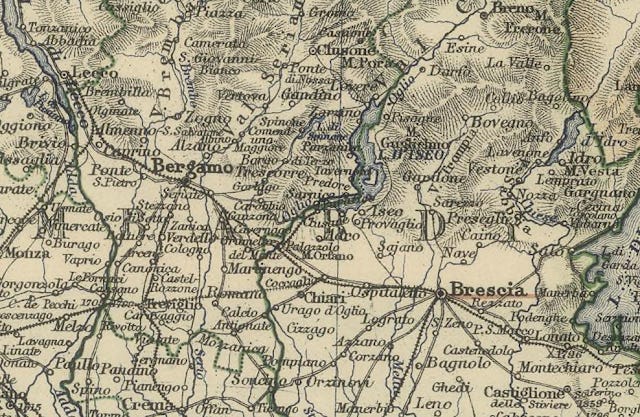

This map shows the region of Lombardy where both Brescia and Gandino are located. You can easily find Brescia towards the lower right of the frame. This was the the destination of the 25 ct letter. Gandino is located northeast of Bergamo, which is located towards the top and left.

Clearly, Bergamo and Brescia are larger cities and both show a rail line that runs through them on this map from 1879. Granted, the letters we are looking at are from the 1850s, but primary routes would have been similar, even if they did not have rail service.

Gandino was smaller. Gandino was not part of a major travel route and it was located in a valley below the Orobian Alps.

Is this a Goose?

Is it possible that our last duck is actually a "goose" in disguise? I suppose it depends on what sort of differences we are looking for. If we are looking for an interesting oddity with respect to the postal regulations of the time, this letter is a fine "duck." It is a clear and simple illustration of the 40 centesimi simple letter rate for an item that traveled over 20 meilen to get to its destination.

However, every other letter we have shown in this Postal History Sunday was between larger towns or cities of the time. If you look at more modern maps, you might come to the conclusion that Guastalla (our first letter) is a smaller community, but its growth was stymied once a decision was made to run the railroad through Gonzaga rather than Guastalla. In the 1850s, Guastalla actually WAS a larger settlement in Modena.

But, Gandino is located in the Alps and, at the time, it was the end of the line. There was no railroad to get there in 1879 and there likely wasn't much for continued traffic beyond that settlement then, much less in the 1850s. Even today, the population of Gandino is listed at around 5000 people, though the tourism industry probably results in a wildly fluctuating number of humans in the area depending on the season.

This simply illustrates a truth for letter mail of the time. Most surviving mail in collectors' hands will be to or from the larger cities and towns. This is especially true for mail that traveled longer distances. But, here we have an item that traveled to an individual in a much less traveled part of the world. I suppose if you are looking for evidence of more rural mail services, this could be a "goose" of a sort, but I think I'll still call it a "duck" for now because it clearly shows a simple letter at the longest distance for Austro-Italian League mail sent from Modena

Unanswered Questions

There are a couple of questions for which I am still looking for answers - despite my efforts to find them for a few years. If anyone reading today’s Postal History Sunday has some leads to share with me, I would appreciate them!

1. Who was Marco Ghirardelli?

Our last letter is addressed to Marco Ghirardelli in Gandino. If you are wondering why the last name is familiar to you, you might be thinking about the chocolate company in San Francisco. However, I am fairly certain THIS Ghirardelli is not directly linked to that particular family. Or, if he is, he does not show up in the accessible histories written about that family.

Here is a portion of a current map of Gandino, clipped from Google maps. Note the names of the streets:

Via Giuseppe Garibaldi, Via Guiseppe Mazzini, and.... Via Marco Ghirardelli.

The first two are well know Italian nationalists who had much to do with the process that led to Italy's unification. Is it a coincidence that Marco Ghirardelli's name is also honored in this area of Gandino? Was Marco Ghirardelli the local hero of the unification movement?

The only reference I have found thus far is that a Marco Ghirardelli from Gandino in 1865 exhibited tools for carding and spinning - as well as a hand loom. I am sure that revolutionaries have to find something to do with themselves when they weren’t running around unifying Italy. So, maybe this is the same person?

I don't know. I'd be happy if someone could point me in the correct direction.

2. What is that black boxed marking?

Sometimes you just have to see another example of a marking to be able to read the one that is front of you. I have not yet been able to decipher the rectangular marking in black. If someone knows what it says OR can point me to a proper resource, I would appreciate it.

While I still don’t know what it says, perhaps I can reward you with a little bit of the "see how one thing builds off another" here.

Note the words "Via Malcontenti" at the lower left on this envelope. My initial reaction whenever I see "via" is to think that this is a directional docket that says, get to your destination by going this way. Things like "via Southampton" or "via Marseille" for example.

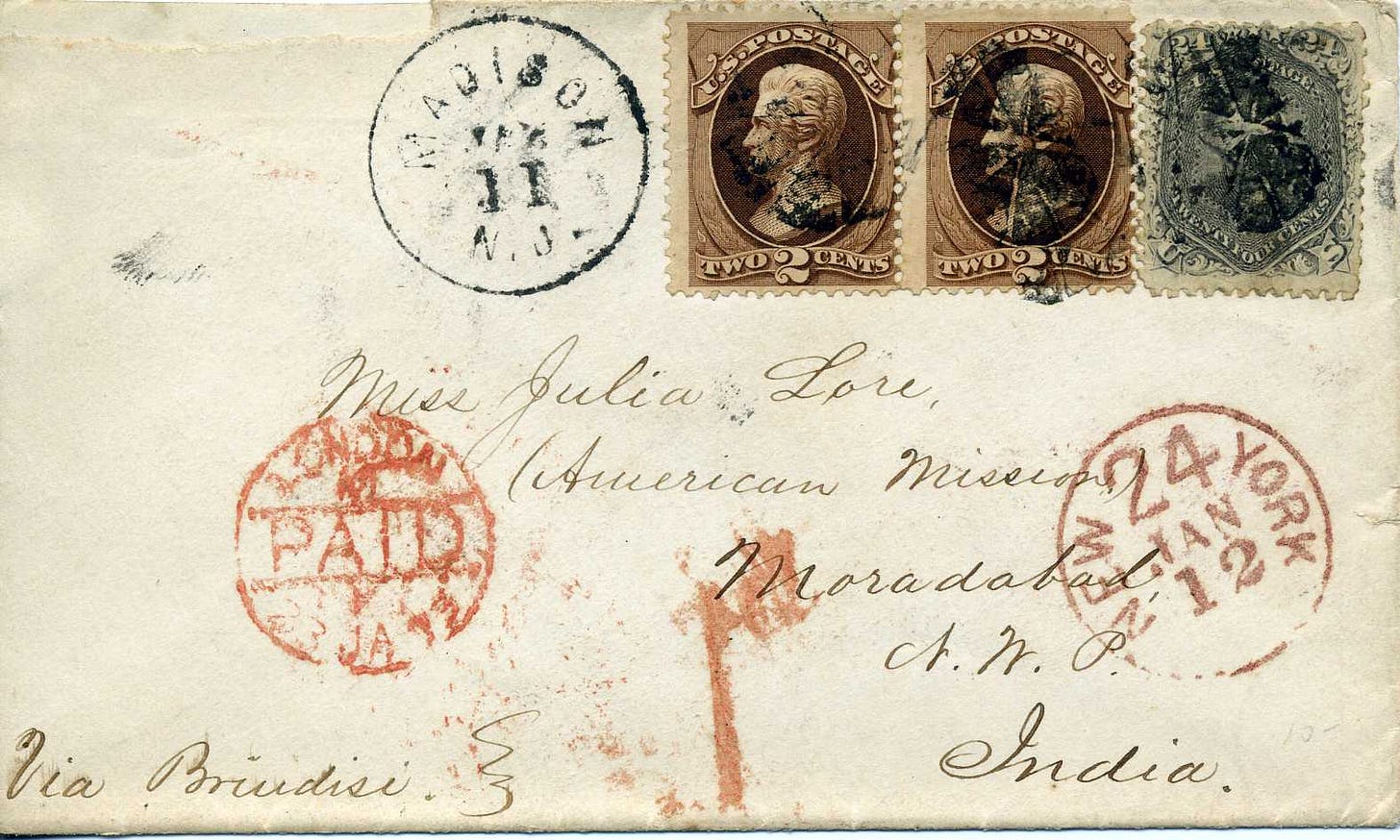

For example, note the words "via Brindisi" on this piece of letter mail from the United States to India below. I know that was a directional docket to route the letter through Brindisi (Italy) on its way to India.

But, if we learned anything from the first question, it's the fact that streets in Italy towns and cities are named in this fashion: "Via Marco Ghirardelli," "Via Giuseppe Garibaldi," and...

"Via Malcontenti"

In other words, this is a street address.

And this is why I always remind myself to be patient when someone from another location on this earth asks me a question that seems simple on its face. I just have to imagine exactly how exasperated someone who lives and has grown up in Italy might be with me that I did not immediately recognize that this was simply a street address. It is possible that someone is amused that I do not know who Marco Ghirardelli is too!

Well, I'm not that proud. I learned something new about street addresses in Italy and I have become curious about a person who appears to have resided in Gandino in the 1850s and had a street named after them. I don't know about you, but I'll call this a good day.

Thanks for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a good remainder of your day and a great week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.