Edward Palk and the Packet Letter Mystery

Postal History Sunday #198

Welcome to Postal History Sunday! It’s time to put on the fuzzy slippers, grab a favorite beverage and find a comfortable place to sit. As for those troubles, hopefully you let them fall out by the fence line near the poultry pasture. I find that late May and early June is a great time to lose things like fence posts, small rolls of chicken wire, and even hand tools, because the grasses grow so fast that things get covered in no time. I don’t see why it wouldn’t work to help you lose those troubles for at least a little while

That is, until you find them again with a mower.

Moving on to today’s topic - we’re going to work on solving two mysteries!

Okay. I will admit that “mystery” might be a bit of an overstatement. You see, I was thinking that putting the word “mystery” in the title might add a little excitement and intrigue. Or maybe I just wanted an excuse to use the words “excitement” and “intrigue” and I felt that “mystery” gave me license to add them to the introduction.

That, in itself, may be another mystery!

The Southampton Packet Letter Mystery

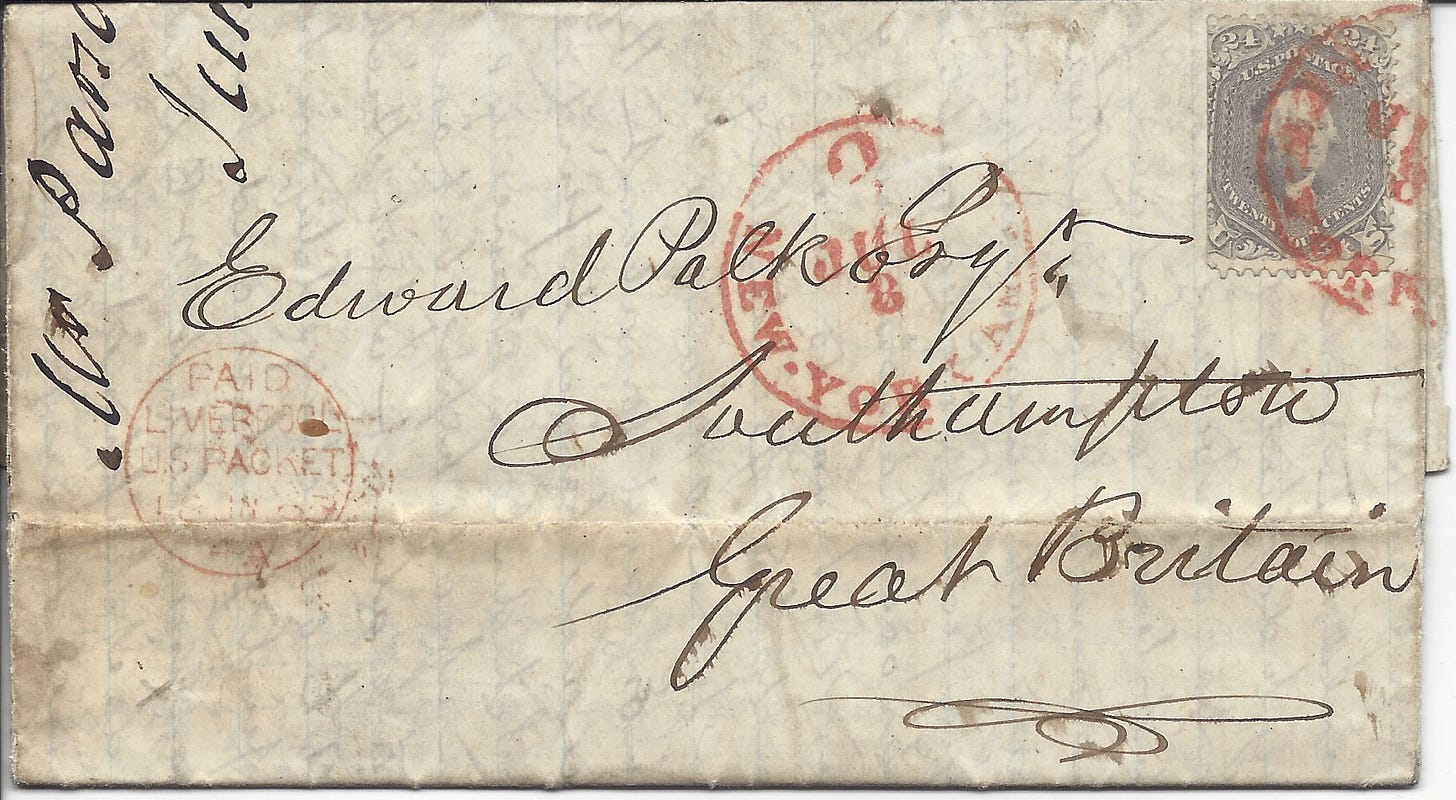

The mystery started, at least for me, when I noticed this folded letter that was sent by John Parsons in Cleveland, Ohio, to Edward Palk in Southampton (England). At first glance, this piece of postal history does not seem all that different from most other simple letters sent from the US to the United Kingdom in the 1860s. A 24-cent stamp pays the proper postage for a letter that weighted no more than 1/2 ounce. A Cleveland, Ohio, duplex postmark was applied to deface the stamp (so it couldn’t be reused) and it shows us that the Cleveland post office processed the letter on January 29. And, a red New York exchange marking tells us the letter left on an American packet (ship) on February 3rd.

It all seemed perfectly normal until I noticed the Southampton marking for February 4, 1866.

This is the the sort of thing that makes postal history fun. A postal historian learns what covers look like when things follow regular processes so they can recognize items that show exceptions to the rule (or the norm). This cover definitely illustrates something different.

But what is it illustrating, exactly? That’s the first mystery for the day.

It might be tempting to state that the date (February 4) was my main reason for thinking this cover is an exception. After all, it wouldn’t have been possible for a letter to get from New York and cross the Atlantic to Southampton in one day.

There are two possible explanations. The simplest answer could be that the postal clerk missed putting the “1” in front of the “4” when they inserted the date slug into their postmarking device. At that time, many postmarks had typeface pieces that could be removed and replaced to reflect the current date and sometimes the time. It shouldn’t be hard for any of us to recognize how easy it would be to get a date wrong.

Yes, I’m looking at (almost) all of you. I am guessing that you can relate to wondering what day it is when asked to sign and date a document. And I am pretty sure that most of us can think of a time when we had a lot to do and we made a simple mistake like this. And, if you are one of the few who can’t relate to this situation, you’re just going to have to trust the majority when we say this would have been a fairly common error.

A second possibility could be that the date selected had something to do with a British postal agent taking control of the mailbag on the ship. This would not be unlike the mail clerks on French mail trains who sorted through and placed transit postmarks on the mail. That could make sense - except that wouldn’t have been the case here. First, letters sent between the US and the UK were processed at designated exchange offices (which were not located on the ships). And second, the ship carrying this letter was under contract with the US, so if there was going to be a postal service clerk, it would not be a British clerk.

Actually, the main reason this cover caught my interest was that I had never seen a Southampton Packet Letter marking on any of the pieces of mail I have viewed during the 1860s that was sent from the US to the UK.

To put this in perspective, I have viewed many, many hundreds of paid letters from that time frame to the United Kingdom and this is the only time I have seen this marking. It is, very clearly, different. The question is “Why?” Why does this letter have this marking when so many others do not?

For example, the cover shown below is a typical “normal” example.

This letter was mailed in Philadelphia in May of 1866. It also has a 24-cent stamp to pay the postage. It has a Philadelphia exchange mark in red and a London exchange marking in red. This cover is like 85 - 90% of the covers that traveled to England in that it shows evidence that it was processed at the London exchange office. Liverpool comes in a distant second. Southampton simply isn’t even a blip on the radar - I have seen none.

But, the Southampton marking sure does look a lot like an exchange marking - even if we might expect it to be handstamped with red ink like the London marking shown above. (note: red ink indicated that the letter was fully prepaid)

That brings me to the second mystery - in a round about sort of way.

The Cross-Writing Mystery

Our second folded letter was also mailed to Southampton in the UK. As a matter of fact, this is ANOTHER letter from John Parsons to Edward Palk that was mailed about a half year earlier than the first. This cover entered the mailbag in New York to cross the Atlantic Ocean on July 8 and was taken out of the mailbag in Liverpool on July 18. The letter was carried on the Inman Line steamship named City of Boston, which arrived at Liverpool on July 18 (which nicely matches the Liverpool exchange marking at the left side of the cover).

There are two postmarks on the back of this letter. One is a London postmark for July 19 and the other is a Southampton postmark for the same day. So, we can guess that Mr Palk received this missive at that time. The docket at the left in dark ink reads "Mr Parsons June 1865." Indeed, the letter inside is datelined "Cleveland, June 1865," which provides us with the date and location for the starting point of this letter. After taking some time deciphering the contents of the letter, it seems it was written over a period of several days, and it appears that Mr. Parsons was traveling as well.

Mr. Parsons used a technique called "cross-writing." The letter starts in a lighter ink in the normal orientation for a piece of paper. The paper was then turned sideways and the letter is continued with a darker ink written over the initial content. While this is a way to double the content in the same amount of space, it probably took much more effort to read it. I suspect it might have been easier if the writer were familiar to you and the references of the time were second nature. But, I still think it might have been difficult to deal with.

This gives you background for my second mystery, which I wrote about in a prior Postal History Sunday.

Why would Mr. Parsons use cross-writing in the first place?

The first thought was that Parsons was attempting to avoid spending more money on postage than he had to. This is certainly a technique that was developed during a time when the cost of mail was extremely high (even higher than the 24 cents required here). This interesting blog by Kathy Haas makes a valid suggestion that cross-writing might not have always been used because the writer was unable to afford the cost of paper and postage. It is possible that this was "an ingrained habit or a practice associated with virtuous thrift."

Is it possible that Mr. Parsons was signaling his own virtue to Mr. Palk by... um... making it really hard for Mr. Palk to read the contents of the letter?

If that were the case, I find the notation at the top of the image above to be mildly humorous. “I have most likely made many blunders which you must overlook for I cannot read it over.”

What does it say when the writer, the person who knows the content best, cannot read it over? If you were cynical, you might say that they couldn’t read their own cross-writing, so it is absurd for them to expect their correspondent to do so.

The Second Mystery Solved?

The letter opens, "My Dear Friend..." But, after taking a few moments to attempt to read this writing, I have come to the conclusion that Mr. Palk was either truly a very dear friend OR this was a passive aggressive way to let Mr. Palk know who was better than whom. On the whole, the letter seems to be quite conversational after initial business content - so perhaps Mr. Parsons really did consider Mr. Palk a "dear friend."

Some of the cross-writing has a notation that reads "July 3," which makes it clear that this letter was written over a period of days. Mr. Parsons follows the date by saying "tomorrow will be a great one for firecrackers and.. speeches." No doubt, in reference to Independence Day celebrations.

This is where we connect some dots by going back to the first letter we featured today. The letter contents are shown below:

What you might need to know at this point is that I was not immediately aware of the fact that both letters were written by the same person to the same recipient in Southampton. It wasn’t until I had done some research and speculation on both mysteries that I made the connection between the two items.

First, it is clear by the content that Parsons corresponded with Palk consistently. It is also certain that they had business dealing of various sorts. Palk was known to be a chemist and druggist (depending on the resource you check), as well as an influential person in Southampton. He served as mayor for a time and had strong connections to the anti-slavery movement in England. He was also involved in works to provide housing for homeless children and a publicly accessible library.

As I read the letter, it becomes somewhat apparent to me that Mr. Parsons is often looking to Mr. Palk for either guidance or support. Parsons is clearly the less affluent of the two and it is possible that Palk was serving in the capacity of a mentor. At the very least, Palk was serving as a business liaison for Parsons in the 1866 letter with the Henry Pontifex and Sons company.

It is very possible that Parsons was frugal by nature and necessity. He used cross-writing partially because he was not as willing as some to pay twice the postage for a longer letter. If we also consider that the Civil War led to shortages in paper, even in the Union states, it is possible it was just easier to keep writing on what he had rather than go out and procure more.

But, the better explanation is that Mr. Parsons had a whole host of reasons to use cross-writing. He was very clearly traveling when he wrote his 1865 missive. He probably found himself with a bit more time to add to his letter knowing that the next ship leaving with the mail was on the 8th, but found he did not have additional paper. When he considered the difficulty of procuring more paper, the added expense of paper and postage, and the likelihood that he felt Palk would be understanding - he selected the easiest solution. He used a technique that was known to him and frequently used during paper shortages - cross writing.

In fact, if you look closely at the 1866 letter in the image shown above, he uses the technique to add “please write soon” about 2/3 of the way down the page.

I do wonder, however, if Palk wrote back after the 1865 letter and said, “Stop that cross-writing stuff! It gives me a headache!” Then, poor John Parsons had to comply, though he could still get in a little dig by asking Palk to write soon by doing just a little bit of cross-writing seven months later.

Back to the First Mystery

So, let’s get back to the first mystery. The Southampton Letter Packet exchange marking.

For those of you who are not postal historians, I can tell you that they are, for the most part, quite willing to help each other out. So, of course, when I asked for help, I received a number of replies. One of those replies came from Dick Winter, who is a respected expert on trans-Atlantic mail during the period I enjoy exploring.

Part of Dick’s response is here:

The use of the Southampton Packet-Letter postmark is quite rare on normal transatlantic mail between the United States and Great Britain. I have seen a couple of covers with this marking on mail through or to Southampton, but never seen a documented explanation.

My explanation is unsubstantiated, but what I would have written had the cover been mine. The 29 January 1866 cover from Cleveland to Southampton was properly paid the 24-cent rate under the 1848 Postal Convention with Great Britain, The 3-cent credit to Great Britain by the New York exchange office clerk was correct for American contract mail service under the convention. The Southampton Packet-Letter postmark obviously could not have been applied at Southampton one day after the steamship departed New York on 3 February 1866. I believe the Southampton clerk did not put the proper date slugs in the marking device, leaving out the “1” before the “4.” On 14 February the HAPAG steamship Germania arrived at Southampton, having departed New York on 3 February 1866.

Aside from the fact that the wrong date was in the marking device, an equal question is why was this marking device used at all. My theory is that on loose letters, those not in the sealed mail bags or letters from non-contract vessels or British mail packets arriving at Southampton, it was used to show how the letter got to Southampton. If there was no evidence of proper prepayment the marking would be used to justify the postage due to be marked on the letter. Since this letter had been fully paid, it served to indicate the arrival at Southampton only. In my opinion, it was placed on this letter, which had hastily been placed on the steamship after arriving at New York too late for the bagged mail, and was a loose letter. Some might say it was erroneously used as an arrival marking; however, if that was the case I would expect more examples of this use would show up in collections than I have seen or have been reported.

When I asked other postal historians for help, I tried not to influence their responses by giving much of my own opinion. So, it felt good to have some of my own thoughts mirrored and then expanded on by Mr. Winter.

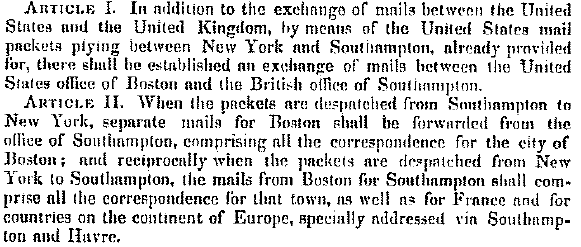

Perhaps the most important thing we should consider is that Southampton was an identified exchange office for mail from the United States. Initially, Southampton could exchange mail only with New York but Boston was added in 1862.

The convention suggested that mails taking ships that sailed from New York City to Southampton would carry mail for Southampton separately from mails intended for the rest of the United Kingdom. In 1865 and 1866, that would include ships sailing with the North German Lloyd and the HAPAG shipping lines. Very little of the mail bound for the United Kingdom was carried by these lines, which carried more postal items bound for the German States, France and the rest of continental Europe.

Most mail intended for England would be delivered by other trans-Atlantic shipping lines that would land in Ireland (which would then go to the London exchange office) or Liverpool. That explains why one of our letters to Mr. Palk in Southampton went through Liverpool.

So, let me put this simply.

Very few letters TO Southampton from the US would have been taken by a ship that would call at Southampton. So, the postal clerks in Southampton wouldn’t be processing large amounts of mail from New York (and Boston) even though they were identified as an exchange office. Even for mail addressed to Southampton, it would go through either London or Liverpool most of the time.

And that’s why this marking is not seen often. It was a normal process for mail that was destined only for Southampton and only for certain ships.

That leads me to believe that the mystery is solved well enough for the time being. But, if you’ve been reading for a while, you know I’ll be looking for more!

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

Ok, everyone! You might have noticed how close to Postal History Sunday #200 we are getting. And, if you haven’t, we’re only a couple away from that milestone.

At present, there are 173 subscribers for Postal History Sunday! This is wonderful and I am honored that each of you have joined me in putting on the fuzzy slippers and maybe learning something new. But, maybe we can have a little push and get to 200 subscribers in time for PHS #200? Let’s give it a little push and see if we can get there!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest