Eight Tiny Reindeer? - Postal History Sunday

It's hard for me to believe that we are now deep into December - Christmas Eve to be exact. After weeks of rushing around trying to do everything all at once, we find ourselves preparing to spend some quality time with family. And since that's exactly what I want to be doing, it seemed right to just have a little fun with this week's Postal History Sunday.

Last year, we did Twelve Covers for a Christmas Postal History Sunday. This year, we're going to do one for each reindeer. If you're looking for me to be super clever with my selections as they line up with reindeer name, it's not going to happen this time around. And, I probably won't dig too deep into any one topic. But, that doesn't mean we can't still have a little fun.

Cupid

Ok, maybe I'll try to a be a little bit clever with my first selection. Here is a simple letter mailed within the United States. The postage rate was 2 cents at the time, so this tiny envelope was properly paid to get to Mrs. Alvin Hill in Ames, Iowa. There aren't any particular clues about where this was mailed, though it could very well have been mailed in Ames.

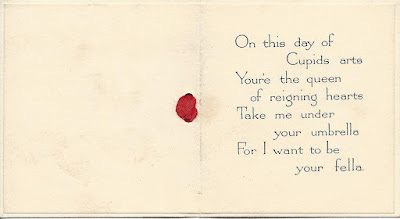

Collectors often enjoy finding the smallest envelopes that were properly and successfully mailed. While this is certainly not the smallest I have seen, it is small enough. And, in this case, I also have the contents - a tiny card featuring Cupid!

No, not the reindeer. But Cupid nonetheless.

Perhaps this particular cover might have been a better selection to share in February, but when I've got to come up with eight covers to share and I look at one that directly links to the name of one of Santa's reindeer, I must use it.

Well, at least that's how I felt.

I'm not going to vouch for the quality of the verse in this tiny card as I do not claim to be a poet of any sort. Still, I am not certain a person scores points for rhyming "umbrella" and "fella" in a Valentine.

I prefer harmony to discord, so I am hopeful that Mrs. Alvin Hill wasn't a poetry critic and found the little card to be charming. Apparently someone did (or perhaps it was just amusing), because this little letter was likely mailed some time in the early 1920s and it has survived one hundred years.

Dasher

It wasn't too difficult to think of multiple options when it came to Dasher. Business correspondence often was sent with a certain sense of urgency, just as this letter from London to Lyon, France, likely was in 1871.

Mailed in London on August 8, it arrived on the 10th in Lyon - which is certainly quite timely. However, this letter was not taken to the mailing office before the mails closed for the day. That's part of the reason why there is a big, bold "L1" in a box on this cover.

Post offices adhered to schedules that were based on the departure times for the transportation systems that carried the mail to and from those locations. So, for example, if the train that was to carry the mail from London to Dover (where it would then cross the English Channel on a steamship) was to depart the station at 10 PM, the mails to depart on that train would close at some point prior to that to allow the postal workers to properly prepare the mail and get it to that station.

For the sake of making a clear example of it, let's say this London East Central (EC) post office closed the mails to France at 9 PM so it could be ready to go on the 10 PM train. Now imagine the poor clerk from Truninger & Company at 41 Threadneedle Street rushing to get to Saint Marten's LeGrand where the East Central London Post Office was located before the mail closes. They enter the lobby, possibly a little out of breath, and see the window to receive mail to France... closed.

The good news for this clerk was that, for a fee, this letter could still go out with the 10PM train. That fee was one penny more.

Two stamps were placed on the letter. One for 3 pence and the other for 4 pence. The price for mail to France was 3 pence per 1/4 ounce. So, this letter must have weighed over 1/4 ounce and no more than 1/2 ounce. Six pence for the letter rate and one more penny to pay for a late fee. Just so this letter could meet the 10 PM train.

Truninger and Company were exchange merchants and according to this clipping from the January 17, 1885 Hunt's Merchants' Magazine, they became insolvent after 40 years of business in 1885, fourteen years after this letter was sent.

Dancer

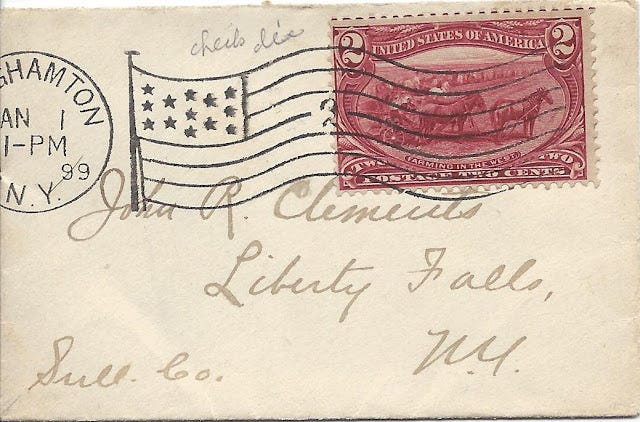

Well, look! Another tiny reindeer... er... cover. This one was mailed on January 1, 1899 at Binghamton, New York to Liberty Falls (also New York). Once again, the 2 cent rate for letter mail was in effect for this letter as it was for our first one.

Sadly, this time I have no contents. I also have no other reason to share this other than the fact that it is a tiny cover to hold a spot for one of the eight tiny reindeer.

For those who are wondering what "Sull. Co." at the bottom left refers to, you might initially think - as I did - that this might be a reference to a company, just as our second item had a handstamp for Truninger and Co on Threadneedle Street in London. But, this time, you would be incorrect. Liberty Falls is in Sullivan County in New York.

Vixen

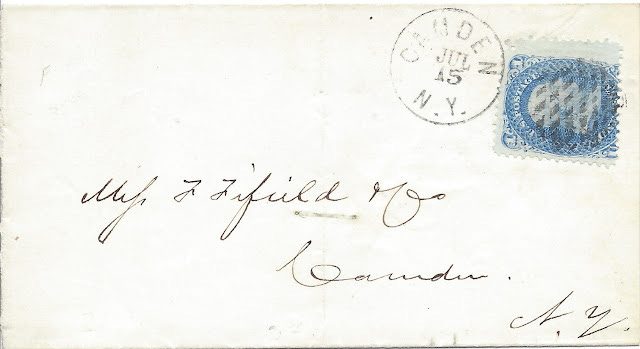

Here is a letter mailed in the 1860s in Camden, New York, for a recipient in Camden. The one cent stamp paid the rate for what was known as a "drop letter." The basic idea was that if a person went to the town post office and dropped a letter there for someone else to pick up, it should not cost the same as a letter that traveled hundreds of miles to another post office location in the United States (3 cents), nor should it cost the same as a letter that would be taken by a carrier to the addressee (2 cents).

This letter was likely sent in 1868, when the 1 cent drop letter rate was effective for towns that did not have any carrier delivery service. In those towns everyone came to the post office to pick up their mail.

While this particular cover is not a "big deal" for its postal history, it does have something sneaky interesting going on (just like a fox, eh... get it? Vixen? Fox? No? Ok, never mind).

The postage stamp on this cover is an example that the production of postage stamps was not always perfect. This sheet of stamps must have gotten hung up somehow in the machine that punched holes to make the perforations that allowed easy separation of one stamp on a sheet from the others. Instead of a nice rectangular stamp, you can see that the bottom and right perforations are askew.

There's even a stray perforation at the top right.

Prancer

Here's a letter that was sent from Buffalo, New York on May 17, 1864 to Albany. This cover was picked up from a post office box rather than delivered to the addressee in Albany. All you have to note is the "Box 713" that appears at the bottom of the address panel to get that confirmation.

The idea of a post office box was an innovation that allowed those who were willing to pay rent for a box to avoid lines at the General Delivery window to check if they had mail. The first locked wooden mailbox door designed for customers to pick up their mail by opening that box was created in 1857.

Also of interest on this particular cover is the interesting cancellation that was used to deface the postage stamp so it could not be reused. For a short while, cancellation devices with cutting edges or punches were used in a few post offices, including Buffalo. If you look closely, you can see that the thin, center circle in this cancellation does cut a bit into the paper of the stamp.

The biggest difficulty with these cancellation devices, in addition to possible damage to the contents, was how quickly they became dull. Collectors of stamps and postal history typically refer to these as patent cancellations.

Comet

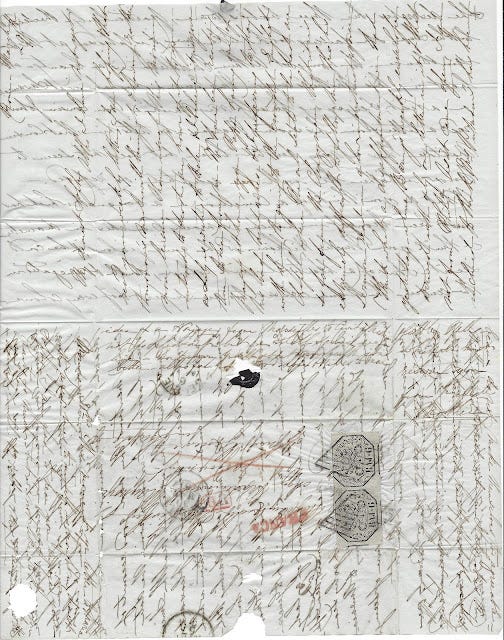

And here is a reminder to us all that postal history items are not always nice, neat and easy to figure out. The item shown above is written on thin, tissue-like paper - probably to keep the weight low enough to prevent the letter from getting too heavy (and requiring more postage).

Like many of us, the letter writer started writing as if they had plenty of space, but eventually found that they had much more to say than they had figured. As a result, they began to cram more and more into smaller spaces. In the end, the letter looked like this when it was mailed.

This letter was mailed on March 30, 1857 from Rome in the Papal States. Twelve bajocchi in postage were applied in the form of two stamps, which was apparently enough for this letter to be properly paid to get to Geneva, Switzerland. There are three indicators that this was the case. The red "PD" in a box, the red "Franco" and the red "X" all tell the same story.

Donner

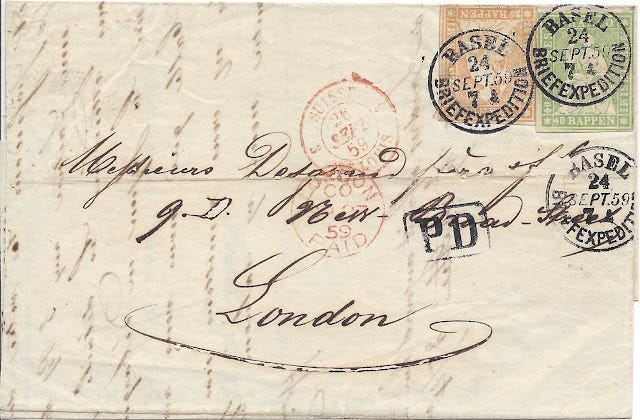

Here's a cover that I think is a pretty example of mail from Basel, Switzerland to London in 1859. There are two stamps paying the 60 rappen rate for mail to England via France. The letter crossed into France at St Louis, went through Paris and eventually found it's way to London - taking three days to get there.

Now, if you look closely at the ink flourish under the word "London," you might notice that the paper is eroding there. In fact, you might notice some small areas in the address where the paper is also gone.

This ink is probably iron gall ink, which does, over time, eat into the paper on which it was applied. If you are interested in a brief introduction to some of the history of inks, you can try this relatively short summary by Lydia Pyne.

And, I know I told you I wasn't going to try to be too clever with my choices - but can anyone guess now why I chose this one to go with Donner?

Blitzen

Blitzen gets to show off an internal German letter mailed in 1916 and we're focusing on both the red label and the purple printing at the top of this envelope. This letter had an extra fee paid for express courier delivery to this cigarette fabricator. Both the label and the purple printed instructions tell us this.

But, an additional instruction at top left says "Nicht Nachts!" - which told the post that a night time delivery was not wanted for this item.

So, while they were in a hurry to get that letter to the recipient, it was likely that no one would be present to receive the letter during the night time hours. Or perhaps, Blitzen didn't have a glowing red nose so he couldn't find the right spot until morning?

Rudolph

Did you actually think I would leave out the ninth tiny reindeer?

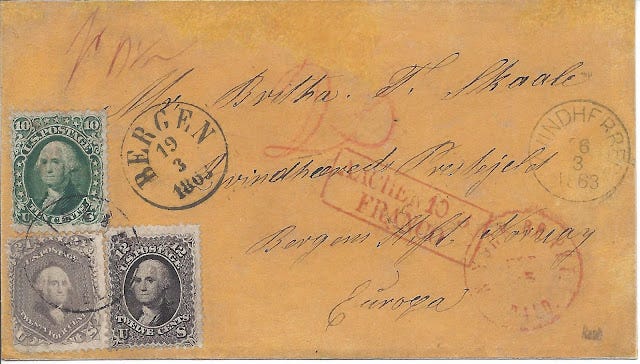

Of course, my Rudolph features a 24 cent US stamp from the 1861 series. This time, it shares a cover with a 10 cent and 12 cent stamp, paying 46 cents for a letter from the US to Bergen, Norway.

Merry Christmas to you all! And, if you don't celebrate Christmas, I wish for you all the blessings that are appropriate for you and yours.

------------------------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.