Entirely Too Late

Postal services around the world have long found it necessary to provide explanation for mail delivery times that did not meet or exceed the expectations of those who send and receive letters. One method was to place a marking on items that were brought to the post office after the scheduled departure of the coach, train, ship or other carrier that was to take the mail. The idea was to make it clear that it was NOT the origination post office's fault that the letter did not begin its journey at the first expected opportunity that the dated postmark, or other markings, might imply.

Project Last Edited: Dec 1, 2019 - 3rd draft

Too Late in the U.S.A.

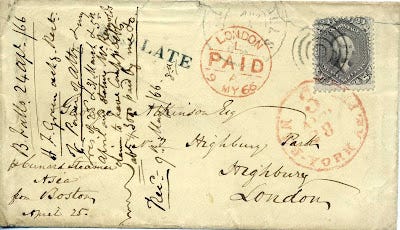

Persons who availed themselves of trans-Atlantic mail services in the 1860s were often well-versed in the comings and goings of the mail packets (ships) and would often write a directive on the envelope or wrapper for a particular ship sailing. In Figure 1, the bottom left of the envelope features the words "p(er) Cunard Steamer Asia from Boston April 25." The docketing at the left seems to indicate that the contents were datelined April 24, 1866 but, sadly, the contents are no longer with the envelope.

Figure 1: Too Late for the trans-Atlantic steamer from Boston

Generally speaking, the postal clerks at exchange offices (those post offices that handled mail to and from countries outside the United States) were charged with getting the mail to the destination via the fastest available route. The docket indicating which ship this item should sail on was not as necessary as it might have been in prior decades. Still the sender of this piece of mail found it necessary to try to show that an April 25 sailing departure was expected. It was well known that Cunard Line sailings left on Wednesdays, alternating between Boston and New York. The next available sailings (by other lines) were on Saturdays. This Wednesday sailing was in Boston, but the letter was mailed in New York, which means the letter probably had to be in the New York exchange office on Tuesday (Apr 24) to reach the Wednesday ship departure in Boston*. But, what happens when you get to the post office too late and the mailbags intended for the Cunard Line's Asia have been closed and are no longer available to stuff one more letter into them?

Well, the postal clerk takes note of your intent for a April 25 departure by putting a stamp that reads "Too Late" on the front of your piece of mail. Then, he strikes the cover with a red New York marking with the date of the NEXT available sailing (April 28), providing an explanation to the recipient that it was NOT their fault that this item arrived a few days later. I wonder if the clerk would have bothered with the "Too Late" marking if the sender had not tried to place an intended departure date on the cover? My guess is that they may not have done so.

*The Appletons' United States Postal Guide gives some of the postal schedules for some of the larger cities including New York and Boston. However, it only provides a look at the Boston foreign mails and no mention is made of the New York foreign mails. In Boston, letters destined for a New York sailing were to be posted no later than 7 pm the previous day.

Apres Le Depart in France

The French were proud of their rail system and the 'star' configuration that set Paris at its center. They developed a mail system that utilized mail processing cars on these trains and there were complex schedules for mail transit using these rail lines. In many cases, rather than going overland via a shorter distance, mail would travel to Paris on one line of the 'star' and then go outward towards its destination from Paris. This often resulted in a faster delivery than a direct coach service would have provided.

Map 1: France's star configuration of rail lines in 1860.

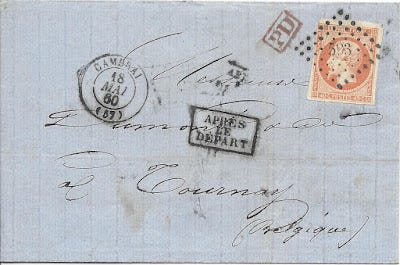

The reliance on rail for mail services raised expectations for timely delivery of the mail, which means a May 18 postmark at Cambrai might result in expectations for a May 19 delivery in Tournay, Belgium. But, every post office had to set a time after which items could no longer be accepted for the scheduled conveyance. Trains, in particular, had a schedule to keep and the mailbag had to be ready to go at the scheduled departure time.

Figure 2: Apres Le Depart

Alas for the individual who mailed this item! The French postal service was sensitive about their reputation for timely mail service, so they applied an "Apres Le Depart" marking to any item that was received after the scheduled close of the mail. It is important to recognize that the closing of the mail for a particular departure does not imply that the post office itself was closed for business. In fact, a post office with any size would likely have multiple mail closing times to reflect mail bound for different directions or conveyance methods.

Figure 2a: Arrival at Tournay two days after mailing.

Sure enough, this letter did not get to Tournay until May 20. I suppose two days for the delivery of a letter may not seem all that terrible in the grand scheme of things. But, we need to remember that the post was the primary method of communication between businesses at this time and there is little that is as impatient as a business awaiting payment or the reply to a serious offer.

The distance between the Cambrai, France and Tournay, Belgium is between 70 and 80 km and they were both located on a rail line with a regular schedule. Next day delivery was not at all uncommon between these locations as long as the mail arrived in time to board the departing train. What is not certain to me is whether mail bound for Belgium might actually go to Paris and then return on a train that may (or may not) go past the origination a second time.

Nach Abgang Der Post in Austria

Austria did not have nearly the rail system that France did, but they did develop rail service to most of the 'major' cities and points in between. Even if the rail line was not completed, mail could ride on the scheduled trains until the end of the line, where they would be taken by coach to either the next segment of rail or to the destination. This was especially true for some of the mountain passes that can be found in Austria. The letter below was mail in February of 1858 from Triest to Pola. There was no active rail line between these two cities on the Istrian peninsula at that time.

Figure 3: Nach Abgang Der Post

Triest was a major port city on the Adriatic Sea and there were significant business concerns that utilized mail services regularly in that community. Pola, at the time this letter was written, was also a port city on the Adriatic that was also a part of Austria*. Sadly, the backstamp is not clear enough to determine the arrival date with certainty, though it looks like February 9 (after a Feb 6 sending date). It does not seem possible that this marking had anything to do with a train since I cannot find any record of railways there until decades later. Instead, it is likely that a mail sailing was missed given the status of both cities as significant ports. A three day period between the two locations seems to support this theory.

*Pola is now a part of Croatia and is known as Pula. The distance, via ground routes, is approximately 140 km between Trieste and Pola.

Dopo La Partenza in Italy

In 1855, Milan was part of Lombardy, which was considered a part of Austria. Parma was a duchy ruled by a member of the Bourbon line, but had as recently as 1847 been ruled by a Habsburg. Thus, it should not be a surprise that Parma was part of a postal agreement (Austro-Italian Union) that maintained favorable rates for mail between members. The letter below was sent from Milan to Parma, which was both the name of the primary city and the duchy.

Figure 4: Dopo La Partenza "After Departure"

Rail service was still extremely limited in the Italian states in large part because Austria worked to suppress development of lines that might support a growing sentiment for the unification of Italy. It would not be until 1859 that the Milan-Bologna line, which ran through Parma and Modena, would be placed into service. Rail service in Milan focused on lines to the East and Venice or the North and Monza. That makes it less likely that this marking, on a letter mailed in 1855, indicated late arrival for a mail train. I suppose it is possible there was a segment of track around Milan that took this item a short distance before it was placed on other ground travel for the rest of its travels.

All in all, it seems to me that a September 2 postmark in Milan followed by an arrival in Parma on September 4 for a 120 km trip by coach. With an average speed of 8 km per hour, it would take 15 hours of continuous travel, but it is likely dedicated mail coaches traveled much faster on average for this route. The letter itself is datelined on September 2, so there doesn't seem to be any reason to prompt the post office to mark this letter as no inaccurate claim was being made by the sender. It is also remarkable to me that this item was disinfected, but still delivered in two days.

Speaking of disinfected mail, this item features two slits that were cut into the letter for fumigation at Parma before delivery. The disinfection process, while already shown to be ineffective from a scientific standpoint, was still being used by some communities in an effort to address outbreaks of cholera (one of which is recorded in nearby Ferrara at the time of this letter's arrival).

Na Posttijd - the Netherlands

Na Posttijd is translated literally as "After Post Time," which clearly fits the same purpose as the items shown above. Wageningen and Arnhem are only 20 km distant from each other and it would not be unlikely for mail to arrive the same day of posting as long as the item were received prior to departure of the mail train.

Figure 5: Na Posttijd

Wageningen and Arnhem were both located on an operating mail line at the time of the posting of this letter in 1858. Once again, it seems that it is likely the Na Posttijd marking was an indicator that the mail train was missed. Perhaps no such marking was used for coach or other service. However, 20 km is equivalent to 4 Hollands Mijls, each of which was equivalent to roughly an hour long walk. Technically, any service could have arrived at the destination in one day as long as the letter was received at the post office prior to the carrier's departure! Sadly, no one was willing to walk this item to Arnhem, so it waited for the mail train that came through the next day and the letter arrived in Arnhem on September 7.

You might notice that this letter bears no postage stamps, something that is uncommon for items in my collection. However, it was not at all uncommon in the 1850's for items to be mailed unpaid with the intent that the recipient pay the postage in order to take possession of the letter. The large, penned "5" on the front of this letter indicated that the 5 cents of postage were due on delivery from the recipient.

Still Too Late - But Why Go That Way?

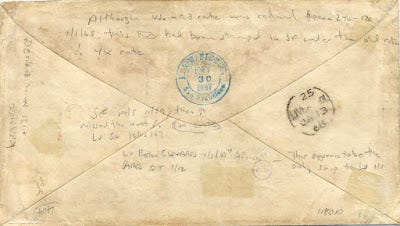

Why would I show an item's reverse side first? Well, that's where the story starts. A company marking for Eric W Pierce shows a date of November 30, 1867, providing some impetus for the postal offices to be a bit defensive if the letter arrived after the closing of the mails for any particular mode of transportation. If you notice the January 13, 1868 receiver from Liverpool, you might conclude (rightly) that a month and a half might be longer than Mr. Pierce wanted the mail to take before it arrived at its destination unless, of course, Eric W Pierce did not really want to report to H&W Pierce in Liverpool. Since there are no contents with this envelope, this is something I will likely never know.

Figure 6: Reverse of letter from San Francisco to Liverpool

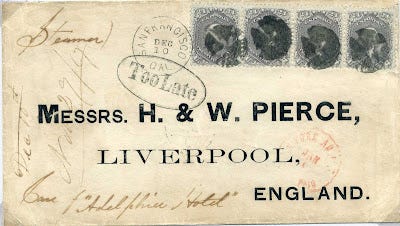

The other side of the cover is the one I normally show off for obvious reasons. This cover represents an item that weight between 1 1/2 and 2 ounces, which required 96 cents of postage to get to England up until December 31 of 1867. The "Steamer" marking at the top left provides us with all we need to know to figure out why the bold "Too Late" marking was applied prominently on this cover.

Figure 6a: Too Late for the steamer from San Francisco

The steamer Golden City left San Francisco on November 29, one day prior to Mr. Pierce's business handstamp on the back. The next scheduled departure for Panama was on December 10, when the Sacramento left port. As a result, the postmaster applied the December 10 datestamp, even though the letter was probably in hand on November 29 or 30. The oddity here is that most mail, by the time we reached 1867, was carried overland. It would still be a year and a half before the 'Golden Spike' was driven at the trans-continental rail line completion, but much of the route did have rail service. In short, it should have been faster to go overland rather than via Panama. So, why was the steamer service opted for in this case? Given the time of year, it could be there were weather delay concerns, but it would be interesting to see if this could be determined.

Ok, You're Late. But not "Too" Late

There are certainly "Too Late" markings in the postal history of the period for Great Britain, but here is something similar but yet a little bit different from 1870.

Figure 8: 1 penny "Late" Fee from London to Portugal

It was typical for post offices to have published 'mail closing' times where items received prior to the mail closing were essentially guaranteed to have arrived on time for the departure of the mails via a particular conveyance. In some cases, especially larger cities (as London above), there were services provided to allow for items received 'after the mails.' In the case above, a one penny fee allowed this item to be added to the departing mail carriage, train or ship despite being submitted after the mail closing time. In the United States there are 'Supplementary Mails' (figure 10) that follow similar pattern and Liverpool provided a 'Floating Row House' (figures 9 and 9a) for the submissions of letters at the dock of a departing ship.

Figure 9: 1 shilling extra for Floating Row House

The item below shows a New York Supplementary mail marking for a letter intended for Basel, Switzerland.

Figure 10: a later Supplementary Mail item in New York

A separate post for various types of supplementary or late fee mail will be in the works some time later this Winter.

Resources:

"Appletons' United States Postal Guide - 1863," D. Appleton & Co, reprint by J. Lee

Lesgor, R, Minnigerode, M & Stone, R.G., "The Cancellations on French Stamps of the Classic Issues: 1849-1876," Nassau Stamp Company, 1948.

*** Bib still in progress ***