Follow-up - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to this week's Postal History Sunday on the GFF Postal History blog or the Genuinely Faux farm blog. Everyone is welcome here, whether you have years of study involving postal history or you are merely curious what it might be that gets a small-scale, diversified farm operator interested in old envelopes that have already served their primary purpose in life. Let's send those troubles off on a merry chase somewhere, and hope they never return, while we explore something I enjoy. And, if we are lucky, you will be entertained and we will all learn something new.

-------

Learning a truly new thing is actually very difficult, especially if you do not have a place in your personal experience to start from. I recall exactly how frustrated I was when I first decided to try and learn things about letter mail during the 1860s. I had very little idea as to where I should start. I didn't know the terminology, I didn't know where to go to find people or books or other resources that could help me learn. I didn't even know what questions to ask to even start with the topic.

I could have just stopped - and I was tempted to do so. But, if I have learned anything about myself, I can be pretty stubborn about learning.

Each new thing learned gives you a stepping stool that lets you reach out to other, related things. Sometimes, the stepping stools you select lead you one way and you end up missing something that becomes obvious when you look back. Today's post is dedicated to things I have been able to reach because of an earlier studies or things that I missed while I was there.

If you wish to visit the related Postal History Sunday to each topic, you can take the link I have placed in the title of each section.

Back in March of this year, Postal History Sunday featured stamps from the US Columbian issue of 1893. The title was For What Ails You because the items featured were from packages that probably contained various pharmaceutical or medical supplies.

Sadly, this particular envelope did not qualify to be included in that post, both because it didn't clearly fit the theme and because it wasn't in my collection at the time. But, the fact that I had recently explored packages in this post led me to consider adding this item in the first place!

The postage on this larger envelope from August of 1893 includes eleven copies of the 4-cent denomination and six copies of the 3-cent stamp, giving us a total of 62 cents of postage paid. The red label with the letter "R" in the center tells us this was sent as a registered item, which cost 8 cents (effective Jan 1, 1893 - Jun 30, 1898), leaving us with 54 cents in postage. And, if you look towards the bottom, you will see the number "54" in pencil, which is a nice confirmation that a postal clerk came to a similar conclusion.

This large envelope was apparently mailed at the foreign letter rate from the US to Germany at a cost of 5 cents per half ounce, but the Universal Postal Union guidelines were based on one rate per 15 grams (Jul 1, 1875-Sep 30, 1907). For the curious, 15 grams is a little more than a half ounce (.529 ounces).

If you are paying attention, you probably are now saying "Wait! Fifty-four cents is NOT divisible by five! What's going on here?" And that's exactly what I said. One clue just might be the pencil "11" at the bottom left. The 11th rate step would be for a weight over 5 1/2 ounces and no more than 6 ounces in the US. So, the amount due would have been 55 cents.

The 11th rate step in Germany would have been measured in grams - over 165 grams (5.8 oz) and no more than 180grams (6.35 oz). Is it possible that this thing actually weighed more than 5.5 ounces and less than 5.8 ounces? From the US perspective, an item that weight would require 11 postage rates, but the Germans would only see it as ten.

Either way, the US postal clerk should have noted it was one cent short UNLESS they were aware of the difference in weights and made a decision to send it as paid using the 15 gram increments as a guideline. It is most likely that the single penny wasn't going to be worth the extra effort and it was ignored.

We'll likely never know, but it is fun to speculate. And this gives me something to stand on that may lead me to explore this item more. If I do, you may see it again in a Postal History Sunday!

"Hyper"

Here's a case where you wonder how things happen the way they do. In the original blog post, I give a summary of how postage rates rapidly increased in Germany during the period of hyper-inflation in the early 1920s. I don't typically go searching for this sort of item, but if I run across something and it looks interesting to me and it is very inexpensive, I might go ahead and add it.

Oh! Ugh! Why would I add THAT?!? It looks pretty beat up and.. what's going on here, Rob? Have you led us all astray?

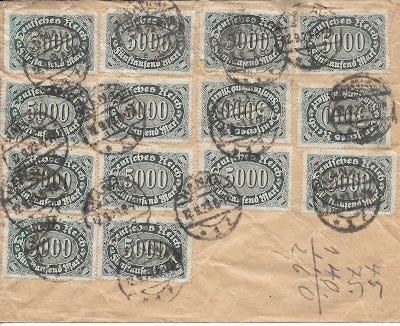

Oooooh! Ok. The back of this cover has another 14 postage stamps at 5000 marks each for a total of 75,000 marks in postage. I guess I was feeling like adding another piece of postal history that had a lot of stamps on it.

This postage rate was for internal letters in Germany that weighed no more than 20 grams and this particular rate only lasted from September 1, 1923 until September 19 of the same year. This letter is postmarked from Hanau on September 12. So, I thought to myself, "Yay! I got an example of a rate in 1923. Those were usually effective for short periods of time!"

Then, I looked at what I had again (go visit the Hyper blog) and I found I actually had something for this particular date range. In 1923 alone, there were seventeen DIFFERENT rates for domestic letters. I pick up two - and they both fall in the same rate period. What are the odds?

So, what did I learn here? I guess I learned why some people have checklists or some such thing when they are looking at items they might want for their collection. But... that's no fun! And, this cost less than the drink you have in your hand... and I had fun researching it.

So, I win again!

Just a couple of weeks ago, I wrote about some letters that traveled across the seas in the 1930s and one of the pieces of mail I featured traveled from the United States to Finland.

I did a cursory look at the addessee, Mr. J.G. Sihvola, but I did not find anything. That's ok, the blog and the story for the cover still held up nicely. However, I recently shared this cover with an online acquaintance who lives in Lahti and I immediately got confirmation that this correspondence is fairly well known by postal historians in Finland. Score one for sharing what we enjoy!

Jorma Sihvola worked at the Finnish Legation in Washington, D.C. for over ten years, starting in the 1930s and remaining through World War II. His correspondence to family in Lahti is colorful, suggesting the possibility that there was a collector or two in the family, and has been distributed to collectors of stamps and postal history over time.

J.G. and Aino Sihvola (husband and wife) had a wool clothing factory in Lahti. Their son, Jorma, had probably not been in the United States for terribly long when he sent this letter.

Just having a name to refine searches brought me to an old newspaper where the likely sender of this letter was featured as a guest for the Singer's Guild in Washington, D.C. That's one way to add a little color to the story.

My thanks to Tapio Hakoniemi for pointing me to this article that features numerous items from the Sihvola correspondence during World War II, including a 1944 letter that suggests Jorma Sihvola had been in the US for a little over ten years. After reading that bit of research, I now have something else to keep an eye out for if I am so inclined.

Another step and something new I can reach out for.

In June of this past year, I took a look at how mail traveled across the Atlantic between the US and two European entities, the United Kingdom and France. I kept it simple there and looked at some of the most common examples of mail that was sent when there was a postal agreement between the United States and these two nations.

But, what was it like when there wasn't a postal agreement between the United States and France?

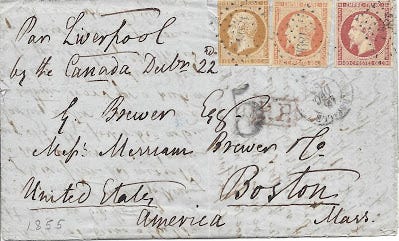

Here is a folded letter that was sent in December of 1855 from France to Boston, Massachusetts. The postal convention was not going to be in effect for another year and a half, so there was no way to fully prepay mail to the US from France. Instead, mail travel relied on the agreement France and the United Kingdom had to pay for all of the postal services UP TO the point the letter was placed in the hands of the US postal system.

Since the British Post Office also had an agreement with the United States, they were able to act as an intermediary between the two nations that did not have a working treaty for the mail.

The cost? One franc and thirty centimes (130 centimes) covered both the French and British postal costs. An additional 5 US cents were due from the recipient in Boston to pay for the US postage costs. That explains the nice bold "5" marking on the cover.

Once France and the United States had a postal agreement, starting in April of 1857, the postage cost for this same piece of mail would have been 80 centimes (15 US cents) and it would have covered the whole trip! This is a case where I stood on my knowledge of mail during the later postal treaty to help me explore backward into years prior to that agreement.

In August of this past year, I wrote about some postal history that showed stamps from the National Parks issue from the 1930s. These are stamps that drew my attention when I was a very young collector, so it makes some sense that I find myself attracted to them even now. When we combine it with my interest for mail that travels from one country to another - we have a winner!

The initial post focused on letter mail that was classified as "surface letter mail." In other words, these were items that used transportation methods that stayed on the Earth's surface (boat, train, carriage, etc). But, air mail was beginning to make its presence known in the 1930s, so it shouldn't be surprising that I might show an example of that mode of conveyance here.

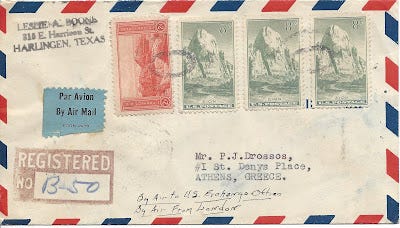

Here is a letter that actually used the air service in the United States, crossed the Atlantic on a steamship, and then used air mail in Europe to get to Athens, Greece in 1935. The cover itself gives me a multiple confirmations that my reading of its travel is correct. A blue label (Par Avion / By Air Mail) states that air mail is to be used. Red and blue parallelograms around the edge also indicated to the post office that air services were desired.

We also have this docket at the bottom of the envelope that may have been a directive to simply confirm what the postage was for. It is also possible this text was added AFTER the letter had gone through the postal services by a collector. I have no sure way of telling, but air mail was new enough that some direction in the form of a docket might have been useful.

The postage costs for air mail went through a number of changes in the early years and some of the calculations could get a bit complex. Happily, this one is not so difficult. We can start with the fifteen cent fee for a registered letter. That leaves us with 11 cents for the letter mail postage.

The US required 8 cents in postage for each ounce in weight (Nov 23, 1934 - Jun 20, 1938), which included postage for the air carriage to the Atlantic port city as well as the Atlantic crossing on a steamship to England. An additional 3 cents was added for each half ounce for air carriage in Europe (Jul 1, 1932 - Apr 27, 1939).

Well, I sure am glad that one added up properly (15 + 8 +3 = 26 cents)! After the big Columbian envelope, I was beginning to wonder.

About a year ago, I featured items that were newspapers and other printed matter items that qualified for a cheaper postage rate. While I am still in the process of researching this one, I felt like this might be a good follow up to show us all another way that we might NOT want to be "In the News."

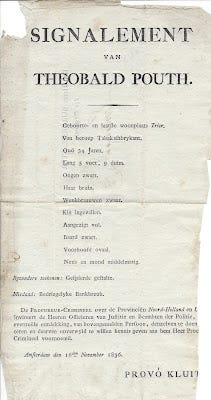

What you see here is a good, old-fashioned "wanted" notice, which could have been posted publicly. Wanted posters weren't just a "Wild West" thing and Theobald Pouth had better have been covering his tracks because the authorities in Amsterdam were looking for him on November 16, 1836!

A rough translation of some of what you see here follows:

Description of Theobald Pouth

Birth and last residence Trier (probably Trier near Luxembourg)

Profession: Tobacco fabricator (makes cigars, cigarettes, etc)

34 years old, 5 foot nine inches, black eyes, brown hair, heavy eyebrows and a sunken chin. Full face and a black beard. An oval forehead

Special characteristics - muscular

Crime: Fraudulent Bankruptcy

The notice was sent from the prosecutor for the North Holland provinces to public prosecutors and offices of the police in the area.

Unfortunately, this item has lost some of the text at the bottom right. When you combine that with the fact that I do not know Dutch well enough to fill in missing words with good guesses, we just have to go with what we have.

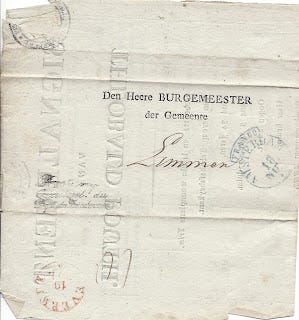

The outside of the document shows evidence of travel in the postal services from Amsterdam to the mayor (Burgemeester) of Limmen, which is northwest of Amsterdam. The red postmark probably reads "Beverwijk," which was a larger town south of Limmen.

There is a "10" by the red town marking that likely indicated the postage paid in Dutch cents. At present, I do not know the postal rates for this area in 1836. So, I do not know if this was a printed matter rate or a letter rate. That just shows you that I continue to seek out and learn new things. Maybe once I learn more this one will make a return to Postal History Sunday?

Put It Out There and People Will Help

The danger of putting things out for anyone to read is the fact that people who know more than I do about something will roll their eyes at my feeble attempt at figuring it out. The benefit is that many of these people take the time to help me to learn something new (or unlearn something that's wrong).

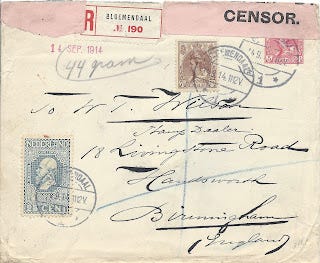

For example, Sören Andersson was very kind to point out an error in my analysis of the fourth item in Sneaky Clues. The registration fee for incoming mail from the Netherlands WAS 10 cents, which makes the whole thing far easier to understand and, sadly, a little less interesting - in my opinion. But, it is always better to make it right! So, I'll be fixing that blog post at some point in the future! He also advanced the idea that the "8" on the last cover could have been a room number in the hotel. We'll still never know, but it is another option!

John Barwis pointed out that I left the passengers on Newfoundland in Run Aground! Passengers took the St George (a steamship) and got to Glasgow about the same time as the mail (July 11). That helps close this story a bit better.

In the post titled Business, Madness and Social Betterment, I included a small section about the rapid collection of mail by mail trains. Rick Kunz mentioned a short documentary from 1936 titled Night Mail. For those who might enjoy learning more about efficient ways to put mailbags on and off trains, here you go!

And then, Winston Williams has also been kind enough to provide useful thoughts and information. In There and Back Again, he points out that a big reason for the US Notes marking is that the agreement with the British did stipulate that compensation be done using specie (essentially precious metal) which had a different value than paper money. And, in Poo d'Etat, he pointed me to a resource and a rate for an item I did not successfully dig out for myself.

Thank you to everyone who provides me with corrections and additional information! I may have missed a few of you here, but it has all been appreciated.

------------------------

There you are, another Postal History Sunday has been released "into the wild" to find audiences wherever it will! I hope you enjoyed today's mishmash of items and that you were entertained and, perhaps, learned something new.

And, a quick reminder that I do accept constructive feedback, including corrections, additional information, and pointers for resources. There will certainly be times when I will omit information on purpose for the sake of readability or due to time restrictions on my part. But, that doesn't mean you can't point omissions out! You honor me with your responses and care in providing them.

Have a wonderful remainder of your day and a productive week to come.