Forward! and The Mystery of Joseph Cooper - Postal History Sunday

Well, here you are! Viewing the 158th entry of Postal History Sunday, a weekly blog written by me, Rob Faux, so I can share something I enjoy - postal history.

It is not required that you know much about postal history to enjoy these articles and you are also quite welcome if you do know a lot about postal history. My goal is to write in a way that makes the topic accessible and enjoyable for as many people as I possibly can. I do take feedback and I am willing to answer questions. I will even try to explain things several different ways if my first choice of words leave you confused or unsatisfied!

This week is actually a continuation of last week's entry titled "Forward!" While it is not necessary that you read that blog to understand this one, you certainly can if you want to. Either way, take those troubles and put them in a blender and set it on high. They won't be recognizable when you're done with that. Grab a snack and a favorite beverage and let's see if we can learn something new today!

More Forwarded Mail

As I mentioned last week, the problem with people moving around from one location to another is not a new problem for postal services. And, it is not difficult to find examples of mail that was sent successfully to one location only to find that the recipient had moved on. If there were instructions for sending the mail to a new location, then that letter could be forwarded through the postal services.

Postal historians use the general term redirected mail for any postal item that had it's routing changed in the process of getting from its origin to the eventual destination (wherever that may be). This could include mail that was routed around a battle zone or a natural disaster. Another example of redirected mail would be a letter that was delivered to the wrong address by the postal service and they had to work to remedy that problem by taking it to the correct location.

Forwarded mail is a special case of redirected mail. To qualify, the item had to be delivered to the correct post office for the address, only to find that the recipient was not there. At that point, the options are limited by whether a new address is known. If it is not, that brings us to other topics, like returned mail or dead letter mail. But when a location is known and the item is forwarded, there are three different ways I classify them:

The letter is forwarded and the extra postage is paid once it gets to the recipient

The cost of forwarding is already paid and the letter is sent to the new location without postage due.

The postal service offers free forwarding services, so no additional postage was needed.

Postage due on delivery

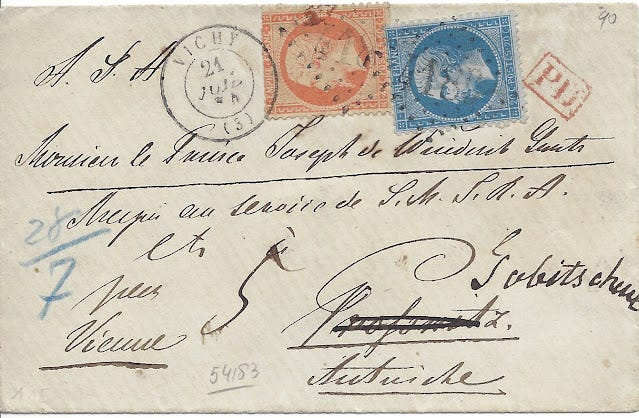

Our first item illustrates a case where the letter was forwarded to a new location and the postage was due upon delivery.

This cover was mailed in the mid-1860s from France to Austria. The postage rate was 60 centimes, which is properly paid by the postage stamps. All of the markings for a typical, paid letter from France to Austria can be found on this letter. But, this letter was forwarded to a new location and Austria wanted that postage to be paid. So, they placed a "5" on the envelope which indicated that 5 kreuzers were due from the recipient once the letter caught up with them.

No postage for local forwarding

And here is an example where a letter was actually forwarded to a new location but no additional postage was required. In this case, the original address (Portman Square) is served by the same office as the new address (Cavendish Square) - both in London.

At the time this letter was mailed (1867), the British Post did require additional postage for forwarding if the new address was serviced by a different post office. The marking just under and to the left of the postage stamp that is shaped like a ring (with an "R" inside) was an indicator that the letter was redirected for free.

If you'd like to see more about this item and see other items that did require postage, you might enjoy the Postal History Sunday titled With This Ring.

Free forwarding of the mail

Eventually, mail forwarding became a free service in most postal systems. Shown above is a 1935 letter that was sent from Brooklyn, New York, to a ship due to land at San Juan, Puerto Rico. The sender was clearly aware that the recipient might have already departed the ship by the time the letter arrived and provided an address for forwarding. Sure enough, Mrs. Rosemary Rabus had left the ship. The original address was crossed out and the letter was sent to the second address provided.

The second address was the General Delivery window in the Juana Diaz post office. Anyone could come to the post office to check if they had mail to be picked up via General Delivery, but there was always a danger that a person would not necessarily know to go there. In this case, it seems that the sender and the recipient (likely related and probably married) were both aware of the plan.

No mystery for Lionel Sheldon

And now we bring back one of our covers from last week. This was our example of a simple letter that was forwarded and the cost of forwarding was expected to be paid at the new destination. Initially mailed on September 4 at the Hamilton, Ohio post office, the Cleveland post office forwarded the letter to Elyria, Ohio. The Cleveland postal worker put a "Due 3" marking on the envelope to make it clear to the postmaster there that three cents in postage were to be collected on delivery.

I ran out of time last week to share a bit of the social history that surrounds this particular item. The letter is addressed to a "Mrs. Col. Lionel Sheldon," and it was sent care of "Horace Kelley, Esq." Pencil markings show that the letter was forwarded to Elyria, care of "I.L. Cole."

The "Mrs. Col." was the spouse of Lionel Sheldon. Formerly Mary Greene Miles, she had married Sheldon in 1858 at the age of 17. Her father was a merchant in Elyria, so it is not surprising that she might have gone there to visit. This might have been especially true if Lionel were away due to his involvement in the Civil War.

Unfortunately, the contents of the letter are no longer with the envelope, so we can't confirm who the letter was from or what it was about. Similarly, there is not much written about Mary, though there is reference to her "officiating at the White House" because President Garfield's wife was in poor health. On the other hand, a great deal can be learned about Lionel Sheldon.

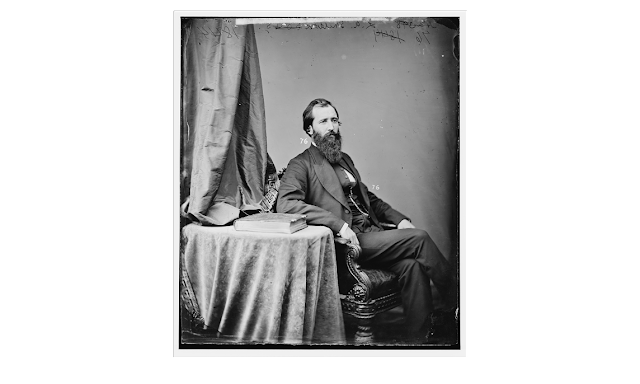

image from Library of Congress

Lionel Allen Sheldon (1829 - 1917) was born in New York and raised on a farm in Ohio. He attended Oberlin College and law-school, being admitted to the bar (becoming a lawyer) in 1851 and settled in Elyria where he most likely met Mary. In addition to being a judge of probate, he was strongly involved in politics, supporting John C. Fremont at the Republican convention in 1856. He was also involved in recruiting for the Federal armed forces at the beginning of the Civil War. He had reached the rank of colonel in 1862, commanding the 42nd Ohio infantry (after serving as Lt. Col. under Garfield).

Sheldon was wounded in the Battle of Port Gibson (May 1863), but he recovered to participate in the Siege at Vicksburg (mid May to early July 1863). The conflict at Thompson's Hill (Port Gibson) is likely where he took his wound. A first hand account indicated that "[t]he heaviest loss by any regiment in our brigade was in the 42d Ohio, who had about seventy killed and wounded." (account by Cpl Theodore Wolbach, May 1, 1863)

Map found in the book The Forty-Second Ohio Infantry - A History of the Organization and Services of That Regiment in the War of the Rebellion, 1876 - F. H. Mason, Cobb, Andrews & Co., Publishers and reproduced here.

By the time we get to 1864, Sheldon was in Louisiana where he was a brevetted brigadier general of volunteers, supervising repairs of levees and fort structures. He settled in New Orleans and was able to take up his legal practice again starting at the end of 1864. It is about that time (perhaps earlier) that we can assume Mary might have been able to rejoin him. So, we can make a guess that this letter to Mary was sent in 1863 or 1864, perhaps as early as 1862. However, most evidence points to 1863.

Sheldon would serve as a US Representative in Congress from 1869-75 for Louisiana, returning to Ohio in 1879 to help forward James Garfield's cause to become President. In 1881, President Garfield named Sheldon Governor of New Mexico territory.

And, as far as Horace Kelley is concerned, he too is a name we can track easily. He was a part of a family with strong ties to early Cleveland history. He was married to Fanny Miles, who was also from Elyria, Ohio. This gives us some of the connections we need to understand why Mary Sheldon might have been visiting the Kelleys - and why Horace might have been receiving mail addressed to her.

So, did you catch the little tricky fact that links these two men? Lionel's wife was Mary Miles. Horace's was ... Fanny Miles.

The Mystery of Joseph Cooper

That brings us to this folded letter that we also showed last week. This letter was mailed in June of 1866 to Dubuque, Iowa. It was forwarded to Washington, D.C., where Colonel H.H. Heath was then stationed. As of July 1, 1866, forwarding of mail no longer required additional postage, so this would have been forwarded for free anyway. But, because Heath was in the military, this letter would have qualified for free forwarding even before July 1.

But, while the postal history part of this item is interesting, it's the contents of the folded letter that grabbed my attention the most.

The letter is datelined June 27th, 1866 from Box 535 in Madison, Wisconsin.

Sir,

I take the liberty of addressing you, on behalf of Mrs. Joseph Cooper, a highly respectable lady of this city, who is, with a family of six young children, in great sorrow and distress.

Her husband, Mr. Joseph Cooper, a medical man by profession, served in the 7th Iowa Cavalry, as Veterinary Surgeon, or Medical Assistant, down to the month of December last, since which time she has not heard from him; and she is ignorant whether he is alive or dead.

Mr. [Orville] Buck, who states that he served in the same regiment, has informed Mrs. Cooper that her husband, in a somewhat excited state, left Fort Laramie on Christmas night last. I have therefore to request the favor of your informing me, if in your power, whether Mr. Cooper afterwards returned to the regiment, and whether he was duly mustered out, or is absent without leave, and what has become of him, if you happen to know anything of whereabouts.

Your early compliance with this application will be an act of real kindness to a worthy woman and very interesting family, and will be a favor to,

Yours most respectfully, Wm Petherick, Justice of the Peace.

Now, imagine you were Mrs. Joseph Cooper. Your husband is part of the 7th Iowa Cavalry and you haven't heard from him for many months. Then you hear from an individual who apparently was in the same company that your spouse left Fort Laramie, Wyoming - at night - at a time of year when temperatures were rarely above the freezing mark.

Yes, I think we would all have been worried.

Map from Wyoming history site.

Beginning with the Lakota Uprising in Minnesota (1862), tensions between Native American nations and the United States continued to increase. The opening of the Bozeman Trail, which traveled through Nebraska and Wyoming - taking people west to Oregon - was seen as an incursion into prime buffalo hunting lands that had been recognized as belonging to the Lakota. The Lakota, with their allies the Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne stood in opposition to the development of the trail and the establishment of forts, settlements and telegraph lines along that route.

If you take this link to a piece written by Doug Fisk and hosted by the Fort Kearny Historic site, you can get some of the feel for what it might have been like for members of the 7th Iowa Cavalry. In this work, Fisk quotes Alson Ostrander who was posted to Fort Reno as a clerk in 1866.

“As we got farther into the Indian country, I found that the enthusiasm for the wilds of the West I had gained from ... dime novels gradually left me. The zeal to be at the front to help my comrades subdue the savage Indians ... also was greatly reduced. My courage had largely oozed out while I listened to the blood-curdling tales the old-timers recited.

“But I was not alone in this feeling. When we got into the country where the Indian attacks were likely to happen any moment, I found that every other person in the outfit, including our seasoned scouts, was exercising all the wit and caution possible to avoid contact with the noble red man. Instead of looking for trouble and a chance to punish the ravaging Indians, the whole command was trying to get through without a fight. Our little force we knew would be at a serious disadvantage should old Red Cloud sweep down on us with his horde of angry warriors.”

The 7th Iowa Cavalry's history is described at the IAGenWeb site and provides opportunities to get an idea of where Joseph Cooper might have been while serving and what he might have had to deal with. Six companies of the 7th Iowa marched from eastern Iowa to Omaha in July of 1863 under the command of Major H.H. Heath, who is our addressee for the folded letter as Colonel H.H. Heath. Additional companies left for Omaha in 1864, apparently taking Joseph Cooper with them. Once at Omaha, companies and detachments were assigned to different posts throughout Nebraska, Kansas, Dakota and Colorado territories, spreading just over one thousand men over a wide area.

We find Joseph Cooper of Madison, Wisconsin, in Company F, enlisting on January 19, 1864 and mustered just under a month later. Joseph is listed as having been born in England and was aged 45 years at that time. It is possible that he was conscripted rather than a volunteer. The Enrollment Act of 1863 required every male citizen and all immigrants who had filed for citizenship between the ages of 20 and 45 to enroll. Quotas were then assigned to each state and congressional district. If a district was behind quota, they could fill the quota by conscription (selecting and requiring members in the enrollment lists to join).

Given Joseph's age and the fact that he had six small children, I imagine that he did not volunteer for service. It is also likely that he was not affluent enough to avail himself of the commutation option (pay $300 and you don't have to join) and he may not have been willing or able to find someone to take his place.

So what did happen to Joseph Cooper?

Sketch of Fort Laramie, 1867 by Anton Schoenborn in Fort Laramie National Monument by David Heib

And so, we find Joseph Cooper in Fort Laramie on Christmas Day after having served nearly two years. There had likely been a Christmas celebration as there was in 1866. He had been away from his family for a long time, may not have volunteered for the job in the first place, and dealt with difficult conditions regularly as part of the 7th. And... he was looking at just over one more year before he could go home.

Orville Buck saw Cooper leave Fort Laramie in an "excited state." And Orville Buck did not report to Mrs. Cooper that he witnessed Joseph's return.

Did Joseph Cooper desert his post? This roster listing suggests that he did so. Dr. Terry Lindell also chimed in with this information:

Regarding Joseph Cooper, Roster and Record of Iowa Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 4, p. 1283, has this entry for him in Company F, Seventh Iowa Cavalry: "Cooper, Joseph. Age 45. Residence, Madison, Wis., nativity England. Enlisted Jan. 19, 1864. Mustered Feb 5, 1864. Transferred to Company F, Seventh Cavalry Reorganized." Page 1415 lists him in Company F, Seventh Cavalry Reorganized and adds this information: "Deserted Dec. 26, 1865, Fort Laramie, Dak."

What is not clear at this point is whether or not Joseph Cooper was captured, returned or died of exposure not long after leaving Fort Laramie. It is hard to imagine a situation where he could have survived alone in the elements for long.

At Forest Hill Cemetery in Madison

The FindAGrave website shows this entry for Joseph Cooper (1818 - 1865) that seems to match, listing him as a veterinary surgeon. His wife, Isabella Waite Cooper (1822 - 1909) and six children also seem to line up with the facts provided in the folded letter that started the search for Joseph Cooper's fate. Isabella's obituary listed on the FindAGrave site may give us a bit more to the story.

In the passing of Mrs. Isabella Cooper, who died at her home at 1025 West Johnson street Wednesday evening, goes one of the early pioneers and staunch women who added so much to the citizenship of Madison in days gone by. Mrs. Cooper was born in Low Green, near Leeds, England, in June 1822. She was married to Joseph Cooper of Skipton, England, in 1843. Mr. Cooper's profession was that of chemist and druggist. He came to this country in 1843 buying a farm in the town of Fitchburg. The family joined him in 1849 and they lived on this farm for several years, then moved into Madison where they family has lived since, with the exception of the years 1857 and 1858, which were spent on a farm in Sauk county. There were ten children born into this home, six of whom grew to manhood and womanhood, and three of whom survive the mother, Mrs. Mary J. Lamont and Miss Annie Cooper who resided with the mother and Mrs. Fernando Knight of Beloit, Kan.

Wisconsin State Journal

Madison, WI

May 19, 1909

The existence of a grave for Joseph Cooper seems to imply that, perhaps, his body was recovered and returned to Madison. Or, maybe, the grave was a symbolic gesture to recognize what seemed inevitable. What does seem clear is that Joseph Cooper never did return home.

And there you go, that's my current best effort for solving the mystery of Joseph Cooper. I hope you enjoyed it! Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

-----------------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.