A single used envelope can open the door to puzzles, interesting facts and compelling stories in history. This week’s does just that!

Let’s put on those fuzzy slippers because it’s time for Postal History Sunday!

What got my attention this time?

This week I am going to leave the time period with which I have the most comfort and look at something a bit more modern. Yes, I know. World War I might not be considered to be recent by many people, but it is about a half century later than much of the postal history I study.

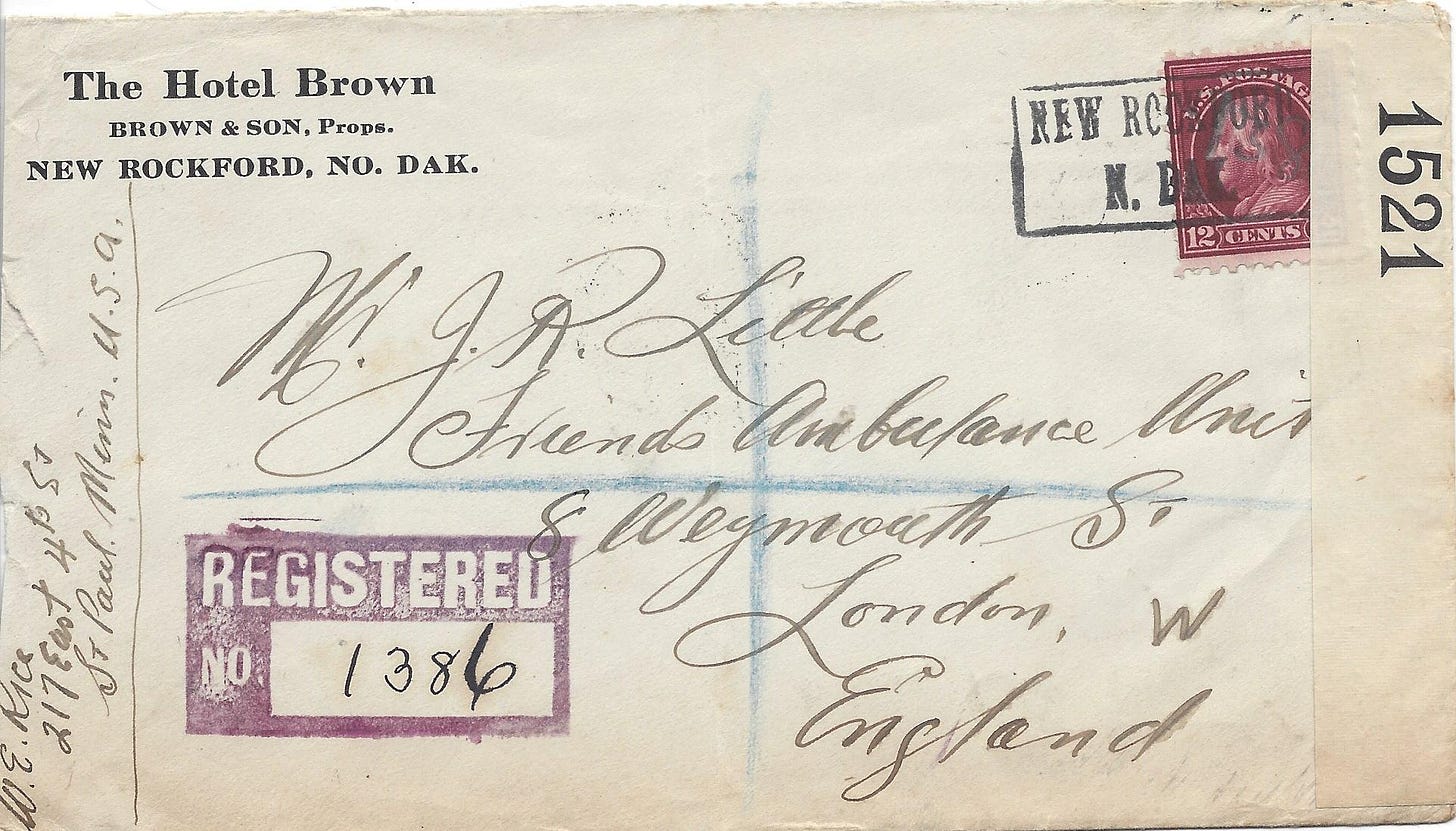

Before I get too far into the postal history part of this item, can you see why I was attracted to this particular cover in the first place? Yes, it is a clean example and it is not impossible to read the handwriting or the postal markings. Yes, it is a piece of mail between two countries (the US and England), which I tend to prefer to domestic, or internal, letters. Also, as we shall see, this letter illustrates a proper postal use of the time (1916).

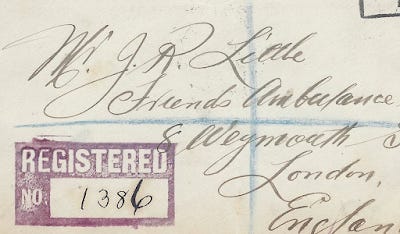

But for this cover, it was the address panel that caught my attention.

"Mr. J.R. Little, Friends Ambulance Unit, 8 Weymouth St. London W, England"

I must admit that, while I was aware of the ambulance units run by the Quakers in World War II, I was not aware of their involvement in the first world war. The gap in my knowledge makes some sense since WW II has received more attention in the US given their involvement in the second war was more significant.

Even if you weren't aware of these ambulance units, you may recognize the movie, Hacksaw Ridge, that followed the story of an American conscientious objector who served heroically as a medic in the second war. Our story today looks at others who held similar beliefs and worked to save, rather than take, lives in wartime.

Getting from here to there

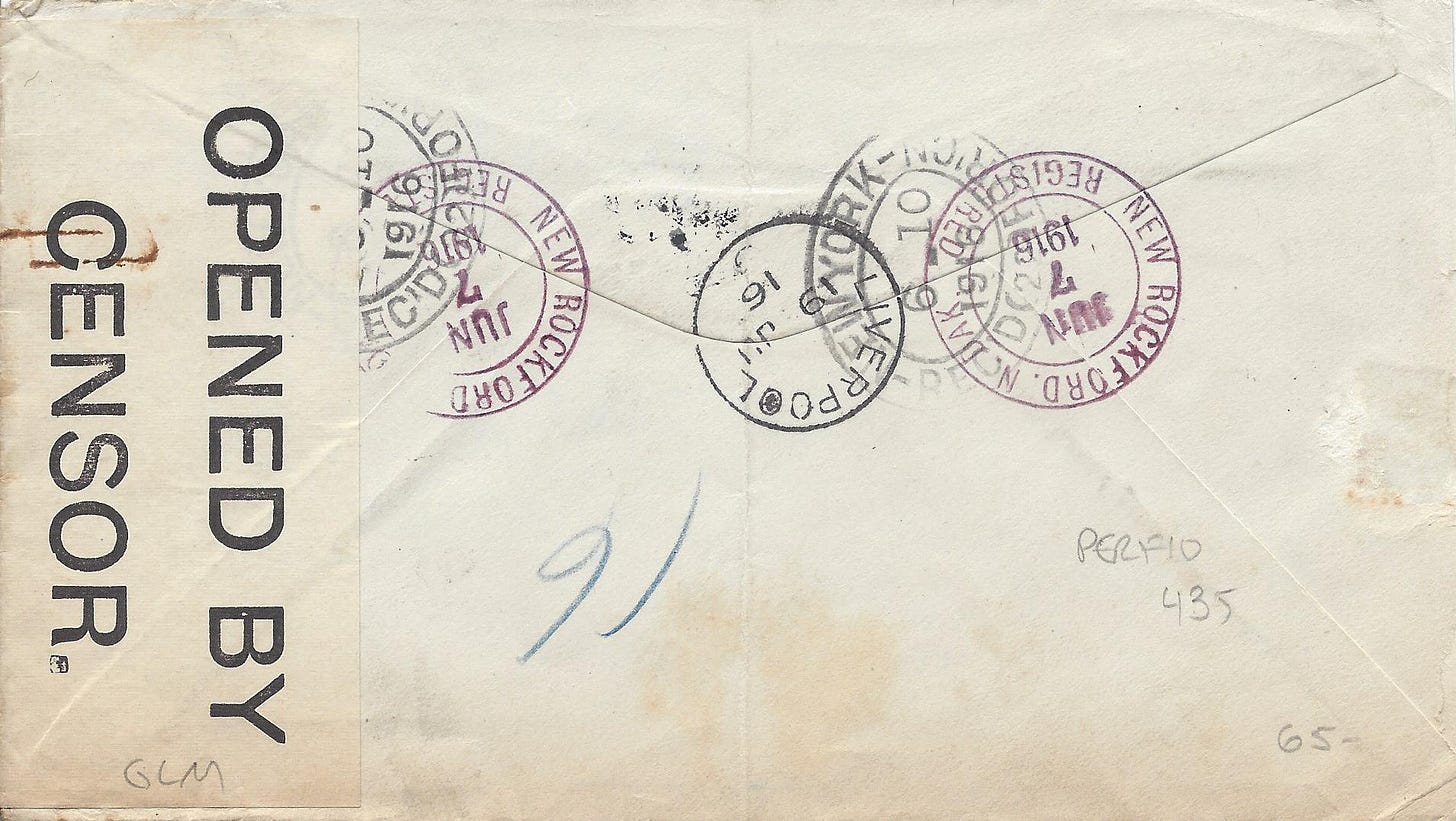

The post marks on this particular cover tell the story in a clear fashion. A rectangular postmark on the front was placed over the postage stamp (so it could not easily be re-used) in New Rockford, North Dakota. The markings on the back are as follows:

New Rockford N. Dak Registered Jun 7, 1916

New York Rec'd For'gn Jun 10, 1916

Liverpool June 19, 1916

I was able to identify the trans-Atlantic crossing that matches the postmarks on this cover by looking at the New York Times for June 10 and June 20 of 1916. The SS (SteamShip) New York was set to leave on the 10th for Liverpool, carrying the mails for “Great Britain and Ireland” as well as for parts of mainland Europe, Africa and the East Indies. The ship was reported to have arrived at Liverpool on the 19th.

The ship was originally known as the City of New York and sailed with the Inman line (1888). It was a two propellor ship and actually held the Blue Riband for the fastest Atlantic Crossing in 1892 and 1893. At the time the New York carried this letter, the ship was fitted to carry second and third class passengers. Once the US entered the war, New York was pressed into duty as a troop transport and was renamed Plattsburg.

What's the "138" thing about?

The postage stamp has a 12 cent denomination and depicts Benjamin Franklin. You can see, if you look closely, that the stamp itself is actually partially covered by some paper tape on the right. And, if you look even more closely, you might notice in pencil the numbers "138" have been written on the stamp itself. I will make an educated guess that there just might be a "6" after the "8," but it is under the tape.

The numbers in pencil on the stamp aren't something I noticed at first, but I find them to be oddly compelling. I have come to some conclusions about those numbers, but I am certainly open to other interpretations if others with more experience in the area would like to chime in.

Let me point you towards THIS part of the envelope. It explains my reason for thinking there is also a penciled in "6" after the “138.”

Registered mail of the time from the US to the United Kingdom had a few characteristics that we can spot on this particular envelope. First, some sort of "registered" marking or label is placed on the front. A tracking number, or ledger number, is included with the marking. I do not think it is coincidence that the three numbers visible on the stamp match up with the first three numbers here.

I cannot give you an explanation for the reason these numbers written on the stamp with any certainty. Maybe the post office in New Rockford or New York knew thought censors might remove the stamp to check for hidden messages. Was this a way to help be sure that evidence of payment was not lost? I do not know.

The next couple of pieces of evidence to show that this was a registered piece of mail include the blue cross marking applied with a pencil on the front. This alerted the British postal service that this item was registered and extra security/tracking was to be provided. Also, take note of all of the dated postmarks appearing on the reverse of this envelope. They are all carefully placed so they overlap the flap - with the idea that it would show that the contents had NOT been tampered with.

But, was this mail "tampered" with anyway?

I find it interesting that some of the processes for registered mail were supposed to provide evidence that the contents had not been disturbed or taken. However, the paper tape neatly adhered to the right side of this envelope was there simply because it HAD been purposely opened and inspected.

This is one way we are reminded that there was a war on. While it would be almost a full year before the United States entered that conflict, the United Kingdom was certainly very much involved. As a result, incoming mail was inspected with the intent of checking for contents or information that could either serve the war effort or, perhaps, harm that same effort if it were allowed to be received unaltered.

Once the item was passed by a censor, tape was applied to reseal the envelope. A censor number "1521" was included on the front side to provide some accountability for the process.

If you would like to learn more about censorship during World War I, I suggest this online article provided by the International Encyclopedia of the First World War and written by Eberhard Demm. The following was taken from that site on October 23, 2024:

"In the Allied countries, postal control was also extended to correspondence between civilians. In Britain, all mail was controlled in special censorship offices either in London or in Liverpool, and in 1918 between 4,000 and 5,000 persons were occupied with this... As the blockade authorities controlled all ships, censors opened all letters and parcels between neutral countries as well. As a result, they closely surveyed the correspondence of German agents and even replaced German propaganda with their own."

Needless to say this slowed the arrival of mail, but the absence of a receiving marking in London means this letter will provide us with no evidence as to how long it was delayed. The Liverpool marking tells us when the letter left the steamship and arrived at the exchange office on the day the New York arrived at port. Based on the description above, it isn't hard to imagine that this was processed by the censors in Liverpool rather than in London.

How much postage was required?

Registry mail services cost 10 cents (effective Apr 1, 1879 to Nov 30, 1925) which was paid by the postage stamp. This leaves us with 2 cents for postage. But the postage rate for letter mail to other countries, according to the Universal Postal Union rates, was 5 cents for the first ounce of weight (Oct 1, 1907 - Oct 31, 1953). That certainly doesn't seem to add up now, does it?

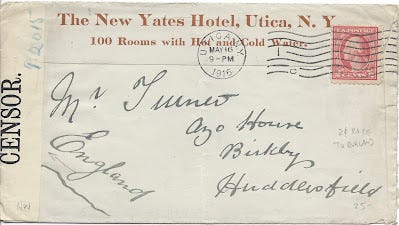

Well, maybe this will help. Here is another letter that was sent in May of 1916 from Utica, New York to Huddersfield in England. This letter only bears a 2 cent stamp and it is not a registered letter.

The United States made some special agreements that provided discounted rates with certain nations, and the United Kingdom was one. In essence, the United States domestic rates applied to mail being sent to the United Kingdom beginning Oct 1 ,1908. This rate was increased to 3 cents on Nov 2, 1917 to help fund the American war effort after they joined the fray.

Mexico and Canada also enjoyed these postal rate discounts from the normal Universal Postal Union rates. Shown above is a 1918 letter where the 3 cent "war rate" was required.

The Social History part

I started the process by doing some reading on the Friends Ambulance Unit just to get a feel for what I was getting into and found this overview to be worthwhile on the Quakers in the World site. Rather that try and craft a summary, I took excerpts from the first few paragraphs to give us all a feel for what the Friends Ambulance Unit was in WW I.

"Philip (Noel) Baker appealed for volunteers [and] Early in September the first training camp took place at Jordans, in Buckinghamshire, for about 60 young men. Initially neither the British Red Cross nor the army wanted to involve a group of independent and pacifist volunteers, but the situation changed dramatically when the Belgian army collapsed in late October. The FAU was provided with equipment and supplies, and a party of 43...left for Belgium.

A few miles out they met a torpedoed and sinking cruiser, rescued the victims, and carried them back to Dover. Setting out again, they came to Dunkirk, and worked for three weeks in the military evacuation sheds, looking after several thousand wounded soldiers until they could be evacuated on hospital ships. The Unit set up their administrative headquarters nearby, at Malo les Bains. There was a terrible typhoid epidemic that winter, and this led to the establishment of the first of four hospitals, the Queen Alexandra, at Dunkirk.

The FAU expanded as the needs grew, and many non-Quakers joined. There were two sections: the Foreign Service and the Home Service... the Foreign Service started on a programme of civilian relief [and] were soon noticed by the French army medical headquarters, and this led to the staffing and running of French ambulance convoys (Sections Sanitaires Anglaises)... In 1915, they started running ambulance trains, and in early 1916 they had two hospital ships.

The Home Service set up and/or helped to run four hospitals in England. Two were in Quaker premises – one in part of the Rowntree factory in York, and the other in a Cadbury house in Birmingham; the other two were in London."

In summary, this was no small operation by the time this letter arrived on the scene.

Looking for J.R. Little

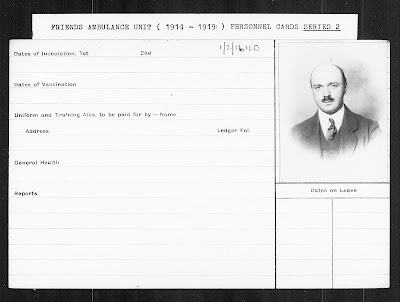

The Library of the Religious Society of Friends in the UK maintains a site where significant primary resources can be accessed. It did not take long using the tools they provided to find personnel cards for J.R. Little. Little has an index card with a photo, but the contents are a bit less detailed than many. The reverse of this card provided some additional detail.

James Raymond Little was a member of the initial group that met at Jordans Camp, undergoing - or somehow involved - in the original training for the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU). The entry for October 30 places him at the "L Office" (London Office). He would visit Dunkirk for a few days in July of 1915, soon returning to London. He remained with the FAU until 1919, after the war had concluded.

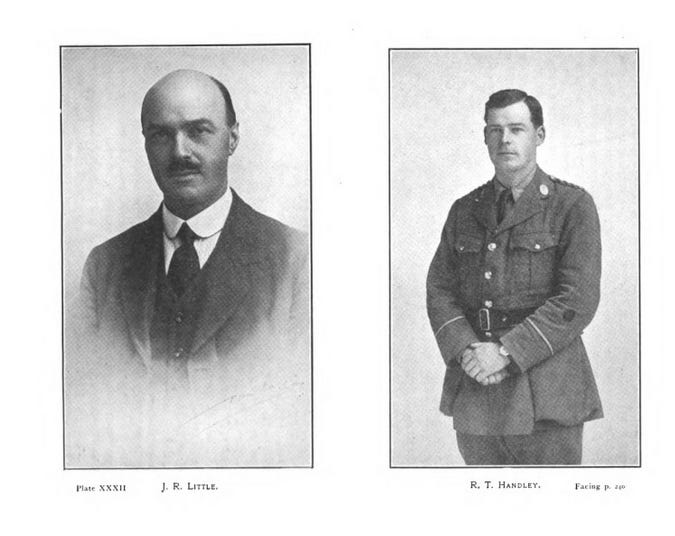

I eventually found this contemporary history (another edition or copy can be found here) of the FAU during the First World War, which gave me the answer I sought - what was J.R. Little's role?

J.R. Little, and apparently his spouse, were the constant force that kept the organizational side of the FAU ...um... organized. If we were hoping for some glamour with this particular piece of postal history, we may not have found it in the direct sense. But we should have known this would be the case simply by the immaculate condition of the envelope. If Little had been working near the conflict, it is doubtful that this envelope would be quite so pristine - if it would have survived at all.

And, if further evidence were needed that J.R. Little was among those involved in the FAU from its very beginning, he is among those listed in the "Committee of the Friends Ambulance Unit" shown below from the text cited earlier.

Once again, let me point out that the FAU was not a small undertaking, with the management of several hospitals, ambulance convoys, ambulance trains and hospital ships. Simply acquiring the needed supplies and getting them to where they needed to be would have been a difficult task.

And remember - the FAU was a voluntary organization. Its members were not paid, so there was significant turnover as individuals found they could no longer continue to serve as a volunteer.

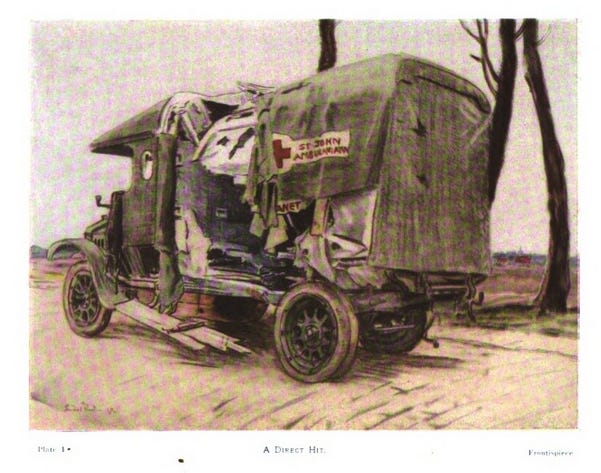

FAU - Not Safe from Harm

Not all members of the Quaker Friends were in agreement as to the role they should play during periods of armed conflict. An excellent article by Linda Palfreeman actually explores the debate and differing opinions of the time. Many felt the Friends Ambulance Unit was in direct opposition the religious tenets that are held by Quakers. Nonetheless, a significant number of conscientious objectors, not all of whom were British and some who were not Quakers, were involved in providing medical relief to those in need due to armed conflict.

Efforts to provide medical help often put ambulance drivers and personnel in the line of fire and they were not immune to the various illnesses that were prone to be found in less than optimal living conditions.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.