I took notice when I typed out the subtitle for this week’s edition as I often do because - well - it’s hard to ignore something I’m typing. The ever increasing number serves as a quiet reminder that I am at least persistent when it comes to my endeavors. This particular number (250) also reminds me that the fifth anniversary of Postal History Sunday is coming up - just ten issues from this one!

My how time flies when you’re having fun.

That is not to say that there aren’t times when a weekly article feels like a burden. But that’s exactly why there are times when it makes perfect sense to take an older article and update it. My learning and process of discovery does not stop at the point of publication. And it only makes sense that, sometimes, a favorite cover is going to get a little love now and again!

Building on an already existing foundation helps motivate me to write. And that motivation often carries over into the following weeks.

So, set the troubles aside and grab a favorite beverage. It’s time to share something I enjoy in the hopes that we’ll all learn something new.

It’s time for Postal History Sunday!

The Allan Line and the Mail

It was the middle of the 19th century, and the Province of Canada was very interested in supporting a trans-Atlantic steamship company that based itself out of Canada. At this point, Canada was relying heavily on the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (aka the Cunard Line) based out of Liverpool, especially when it came to the transport of the mail.

In 1853, the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company (known as the Allan Line) was formed, but their ships were soon commandeered for use in the Crimean War by the Crown. Even so, Allan secured a contract to carry Canadian mail, which it was able to do upon the return of their ships (Oct 5, 1853 - Mar 20, 1856) [1]. At this time, mail contracts were a significant source of income that could make it possible for a new steamship company to succeed.

Allan Line ships departed Quebec City, using a pilot to navigate to Riviere du Loup in the summer when the St Lawrence Seaway was free of ice. During the winter months, the Allan Line left from Portland, Maine to cross the Atlantic.

The Canadian and United States governments reached an agreement in November of 1859 that granted the Allan Line a contract to carry American mail [2]. Mail from the United States was sorted and placed in secured mailbags in United States exchange offices (usually Detroit, Chicago or Portland). Occasionally, a bag from the Boston exchange office (and rarely, New York) would also travel on the Allen Line steamers.

Mail coming from the Upper Midwest of the United States traveled via the Grand Trunk Railroad to get to its departure points, depending on the season.

If you have been reading Postal History Sunday for a while, or if you are someone who knows what I like to collect most, you will recognize that postal history items that have a 24 cent stamp from the 1861 issue of stamps in the United States are my specialty. That explains why I often find that I have extra motivation to dive into the details of items like the one I show above.

Years ago, an acquaintance of mine showed me a scan of this item. They had just added it to their collection and they knew I liked postal history with the 24 cent stamp. Their interest was in the Galesburg, Illinois origin. But, as I looked at the cover, I saw other reasons to be drawn to it.

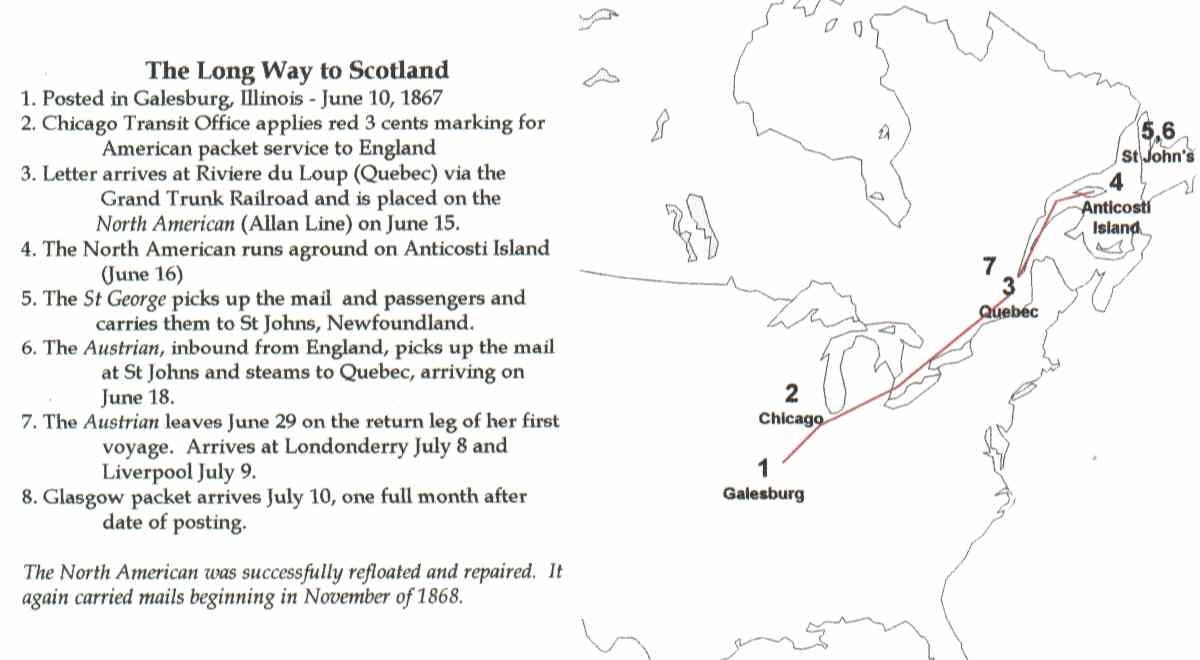

The Galesburg June 10 postmark in blue and the July 10, 1867, Glasgow receiving postmark indicate an abnormally long journey to get to its destination. Galesburg was not terribly far from a US exchange office (Chicago) and the Grand Trunk Railroad should have delivered the mailbag containing this letter to Quebec in no less than two days time from Chicago. The crossing of the Atlantic typically took no more than 10 to 12 days. The dates on this cover tell me this letter was probably delayed for nearly half a month.

Filling in the Timeline

Once again, the first clue that led me to this story was the two postmarks on the cover. The good news is that there are now many resources available to a postal historian to aid in the search for the reasons why a trans-Atlantic voyage might have been delayed.

Shipping tables compiled by Hubbard and Winter in their book (see reference 2) confirmed for me that the North American was scheduled to leave Quebec in the middle of June in 1867. The footnotes provided in the book related much of the details seen above, which I have been able to confirm in period newspapers. With the basics readily in hand, I was able to spend more time finding interesting details related to the story.

The letter was delivered to the post office in Galesburg, Illinois where the blue postmark was placed on the envelope. It traveled by train to Chicago, which housed one of the foreign exchange post offices for mail to be sent to the United Kingdom. The Chicago foreign mail clerk knew that the quickest route should be to send it to Quebec City to catch a sailing on the Allen Line’s steamship North American.

The clerk was going to be wrong about that. But we have hindsight to help us know that and they did not.

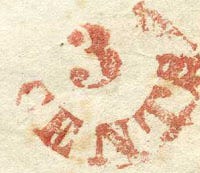

In most exchange offices, each piece of mail was hand-stamped with a red (paid) or black (unpaid) marking that included the city name of the exchange office and a date. Chicago, on the other hand, typically employed a credit marking that gave the amount credited to the foreign mail service with the word ‘cents’ in an arc underneath. They did not usually include a marking with the city name and date.

Mailbags left the Detroit and Chicago offices via the Grand Trunk Railroad to their Quebec (summer) or Portland (winter) port departures [3].

Mails sent from the United States to Britain were governed by the 1848 postal convention which remained in force until the end of 1867. Under this treaty, letters from the United States to Scotland required postage at the rate of 24 cents (1 shilling) for up to a half ounce of letter weight.

The postage collected was split between the British and US postal services in the following manner: 5 cents for US surface mail, 16 cents for the country who contracted the mail packet and 3 cents for British surface mail [3]. The red “3 cents” marking indicated that 3 cents were owed to the British postal system by the US postal system. The Allan Line ship was under contract to carry mails with the United States, thus 16 cents were kept by the US to pay the Allan Line.

After the clerk put a red "3 cents" marking on the envelope, they placed the envelope in a pouch, bundle, or mailbag with other items that were going to go to Scotland. That is where the envelope stayed UNTIL it got to the exchange office in Glasgow - one month later.

The Allan Line steamers that carried the mail stopped at Londonderry (northern Ireland) and Liverpool. Mail to Scotland could certainly be offloaded at Liverpool and taken by train to Glasgow. However, this particular letter seems to be telling me that it was taken by a Glasgow Packet on July 10, 1867. That date was a Monday.

This has been an open question for me for some time. What exactly were these “Glasgow Packets?” I am fairly certain the answer is out there somewhere, but I often run out of time when I focus on the question. The good news is that I think I’m getting closer to an answer.

Using the knowledge that the 10th of July was a Monday AND that exchange markings often used the date of departure for the steamship, I believe I may have found an answer. I believe that the Scotland Packet was likely applied on items that departed on either Monday or Thursday on the steamship Buffalo from Londonderry. This ship (or a substitute) plied between Greenock (near Glasgow) and Londonderry twice a week. Not every letter carried from the Upper Midwest via the Allan Line was taken via this route. If the Allan Line ship did not arrive in time for this departure, it could carry the letter to Liverpool and send it to Glasgow by train or, I suppose, another ship from Liverpool (though the train should have been much faster).

Saint Lawrence Seaway Navigation and the Perils of Anticosti Island

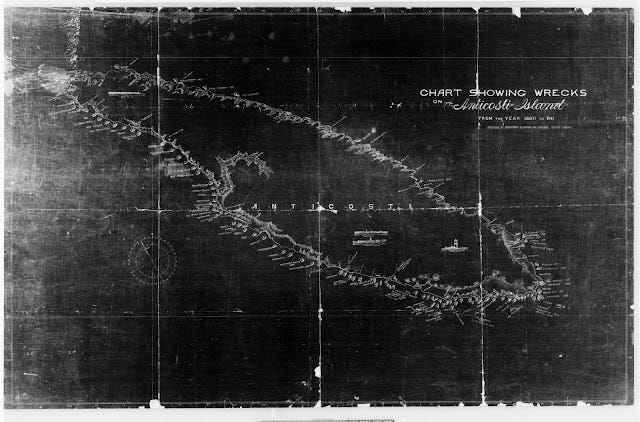

Navigating the Saint Lawrence Seaway could be tricky and it was not uncommon for ships to encounter difficulties in the 1800’s. In particular, the waters around Anticosti Island were most treacherous, with 106 recorded shipwrecks between 1870 and 1880 despite the existence of lighthouses by that time [4]. The island has fully earned the nickname “Graveyard of the Gulf” or “Cemetery of the Gulf.”

For those who might not know, when I reference a "mail packet," I am merely talking about a ship that had a contract to carry the mail. These ships also carried other cargo and/or passengers. After all, a few bags of mail weren't going to fill up an ocean-going vessel.

Anticosti Island can be found at the mouth of the St Lawrence Seaway as it enters the Gulf of Lawrence.

Louis Jolliet, an explorer who initially believed the Seaway would provide a water crossing to the Pacific Ocean, was awarded ownership of the island for his service to New France. Starting in 1680, he ran a fur trading and fishing business from the north shore of the island until it was raided by New Englanders in 1690. After that, his son divided and oversaw operations on the island for the next 40 years [5].

By the 1860s, an estimated 2000 ships passed the island each summer but it was sparsely inhabited [4]. The island is now owned by the Quebec government, serving as a popular game and fishing reserve.

Anticosti Island is not a small obstruction in the St Lawrence Seaway, having 360 miles of shoreline and covering 3100 square miles. It is surrounded by a reef that can reach out a mile and a half from the visible shoreline in places. The reef, combined with a strong current led to numerous shipwrecks resulting in losses lives and property [5].

Strong currents and reefs could certainly be mapped and lighthouses were built to help for nighttime navigation. However, experienced Seaway navigators recognized variations in compass readings could ALSO lead the unwary to run aground. An editorial to the Quebec Mercury in 1827 included observations from a mariner of that time:

“… it would be well that all ships at every opportunity should try experiments on the variation of the compass. I am fully of opinion that it does, and has increased. Since my first coming up the St. Lawrence, and very lately from experiments made, I found six degrees more variation than ever I expected, of my courses steered.” [6]

These variations are known to be due to the shifting magnetic pole and its dramatic effect on compass readings as one goes further north on the globe. The treacherous nature of the waters around Anticosti caused many ships to employ a local navigator for the run into and out of the Seaway.

The North American

The North American was a single screw, 1715 gross ton ship that was originally named the Briton at the point William Denny & Brothers laid the keel in 1855. The ship was launched as the North American on January 26, 1856 and took her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Quebec on April 23 of that same year. The ship was able to accommodate 425 passengers and served as one of the fleet of mail packets for the Allan Line.

In 1871, the ship was moved to a Liverpool – Norfolk – Baltimore route until it was sold in 1873. At this point, the ship was converted to a sailing vessel and was used as such until it went missing in 1885 during a trip from Melbourne to London [7].

On June 16 of 1867, the North American ran aground on the south shore reef of Anticosti Island outbound to the Atlantic Ocean from Quebec. All passengers and crew survived the incident, spending some time on the island. Accounts indicate that they enjoyed picnics of fresh trout and were treated well by a Mr. and Mrs. Burns, who lived on the island at that time.

The home occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Burns was furnished with material from other wrecks and they had survived a shipwreck themselves fourteen years earlier [4]. The St George picked up the passengers and the mail, taking them to St. Johns, Newfoundland. It might seem odd, but the mail was picked up by an incoming steamship (the Austrian) and the mailbag stayed on that ship until it returned. It arrived in Londonderry in plenty of time to take the Glasgow Packet from there.

The North American was successfully refloated and towed to Quebec for repairs, resuming its services to the Allan Line on November 12, 1868.

Bringing all of this back to the present - if you will recall, I had mentioned that someone else was the caretaker for this piece of postal history when I first discovered the beginnings of what is an interesting story. Once I shared my initial findings with the individual who shared the image with me, they arranged for me to become the new caretaker of this piece of history. And, that, as you probably have guessed, encouraged me to continue digging into this story over the years.

The other good news is that this individual also found another cover with a 24 cent stamp that started its journey in Galesburg for their collection not long afterwards (and yes, I was one of a few people that point it out to him).

You have now had the opportunity to read my latest rendition of the story as I continue to learn more about it. I doubt it will be my final attempt as it has become one of my favorite postal artifacts to study.

Resources

[1] Arnell, J.C. Steam and the North Atlantic Mails, Unitrade Press, 1986, p 224-5.

[2] Hubbard, W. & Winter, R.F. North Atlantic mail Sailings 1840-1875, U.S. Philatelic Classics Society, 1988, 129-30,148.

[3] Hargest, G.E. History of Letter Post Communication Between the United States and Europe 1845:1875, 2nd Ed, Quarterman Publications, 1975, p 133-136.

[4] Mackay, D. Anticosti: The Untamed Island, McGraw-Hill, 1979.

[5] Henderson, B. Anticosti Island, KANAWA Magazine, Winter 2003 Issue.

[6] Quebec Mercury #41, Tuesday, May 22, 1827, Page 241.

[7] Bonsor, N.R.P. North Atlantic Seaway, vol. 1, Prescott: T. Stephenson & Sons, 1955, p. 307.

Thank you for joining me. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack.