Halfa No More - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to this week's edition of Postal History Sunday! I hope you have had a good week and that you have taken the opportunity to tuck those worries into a cardboard box and bury them under the other boxes you keep there because... well... they're just good boxes. And you never can have enough good boxes.

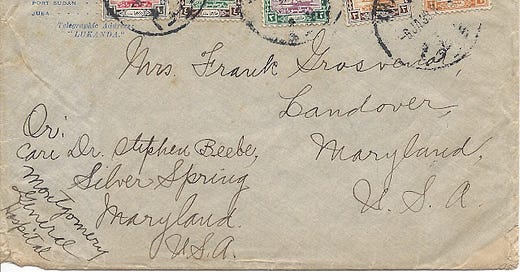

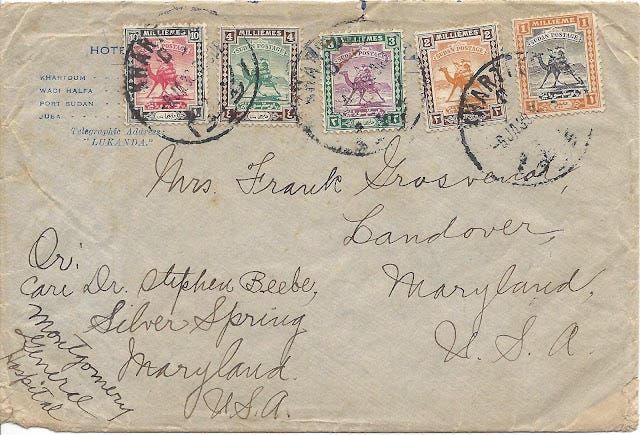

This week, we are going to travel to Northeast Africa and time travel back to 1939 where we will encounter the travels of a letter bearing the images of camels on its stamps. Remember, you can always click on an image to see a larger version of the picture.

Sent from Khartoum, Sudan in 1839 via Egypt by surface mail (boat and land) to Landover, Maryland, I will readily admit that this particular envelope is not the most compelling item if you want to trace its entire route. Once it gets to Egypt, there are no markings that illustrate how or when it gets to the next step.

However, there are so many other ways that a piece of postal history can hook you and keep your interest.

The Stamps Bring Something to the Table

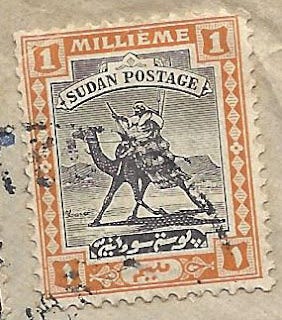

So many stamp designs over the years feature the faces of royalty or statesmen. I have heard the joke that early period stamps often feature a bunch of "old, dead guys" more than once. So, suddenly, you see a series of older stamps that feature camels. It catches your imagination in a new way - perhaps even transporting you to that place along the Nile River where a postman might actually ride a camel to deliver the mail.

The story of the creation of this design, according to the Stanley Gibbons firm, was that the designer, Captain E.A. Stanton, saw the arrival of the regimental post via camel, instead of the normal riverboat delivery. This inspired him to create this proposed design for the new stamps of Sudan to be used as the English asserted their control in that region.

This design was first put in use in 1898 and was still the postage stamp design that saw primary use until the 1950s when Sudan became an independent republic, freeing itself from Egypt and the United Kingdom. Even then, there were some stamps that retained this design - I guess they knew a good thing when they saw it?

According to philatelic lore (philately is the study and/or collection of postage stamps) the issuance of this stamp led to some religious controversy. Stamp paper typically had a watermark (go here to learn what a watermark is if you don't know) that was impressed so that it would appear on each postage stamp. It just so happens that the first issue of the post-rider and camel had watermarks that depicted a stylized rosette featuring a cross. Much of Sudan was populated by followers of Islam who found this to be objectionable. The watermark was changed for the 1902 printing of the design to feature a crescent moon and star to avoid further conflict over this issue.

I mention that this is 'philatelic lore' because I have yet to find a direct reference to the "watermark conflict" outside of the hobby. The earliest reference I have seen thus far is a 1905 paragraph in The Connoisseur: An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors, vol 11. I do not doubt that even something as small as a watermark could be a touchy issue, considering the tensions in that region at the time. An excellent summary of the religious context in Sudan from 1898 to 1914 can be found at this link. Even so, I have to wonder if it was as big of a thing as it is made out to be - after all, there were plenty of other reasons for tension in Sudan. Perhaps stamp collectors sometimes have an outsized idea as to the influence of stamp designs and paper watermarks?

The stamps on this particular envelope were printed on paper watermarked with a series of the letters "S G" for "Sudan Government." This paper was used for stamps created from 1927 and into the 1940s. That makes sense since this was mailed in 1939!

There you are - an example of how the postage stamps on a piece of postal history can take you on a journey that may have little to do with the actual item. No wonder this hobby can be fun!

The First Half of the Journey

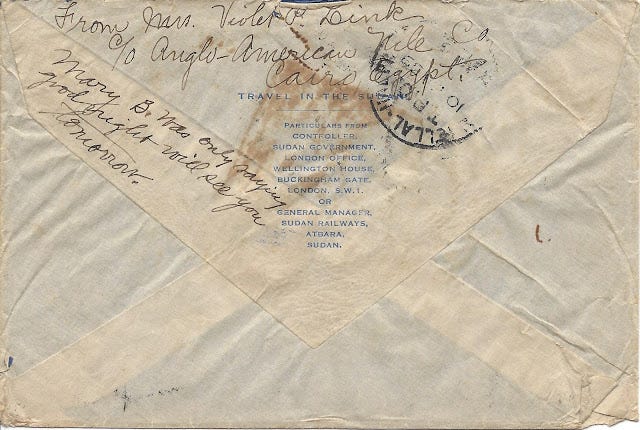

So, the camel stamps got me to consider picking this item up for two dollars. I always liked those camel post-rider stamps, so why not? But, the curiosity in me now wanted to figure out how this letter got from Khartoum to Maryland! The first hint was a poorly struck marking on the back of the envelope. Since I was not particularly good with Sudanese geography, this took me some time to figure.

The marking reads: Shellal-Halfa TPO 10 JAN 39 No 2

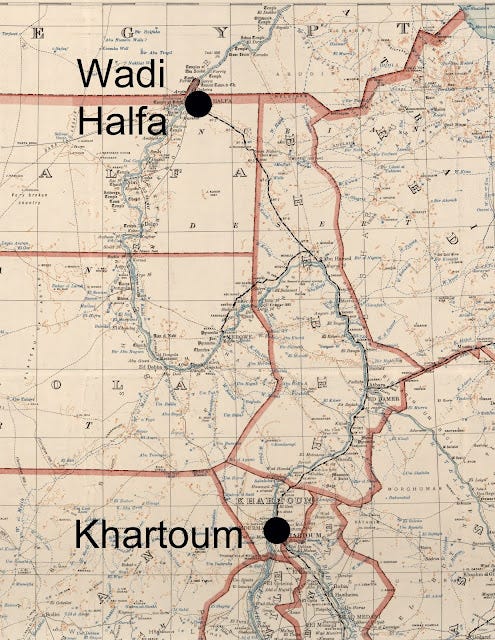

The Shellal-Halfa Traveling Post Office (TPO) connected the Egyptian Sate Railways (El Shallal was the railway station) with the Sudan Government Railways at Wadi Halfa. This piece of railway was 210 miles in length. Until July, 1951, all surface mail from Sudan was sorted on the Sudanese TPO (rather than the Egyptian) and these marks usually appear on the back of each mail item.

Well - now I have some ideas as to where this item traveled!

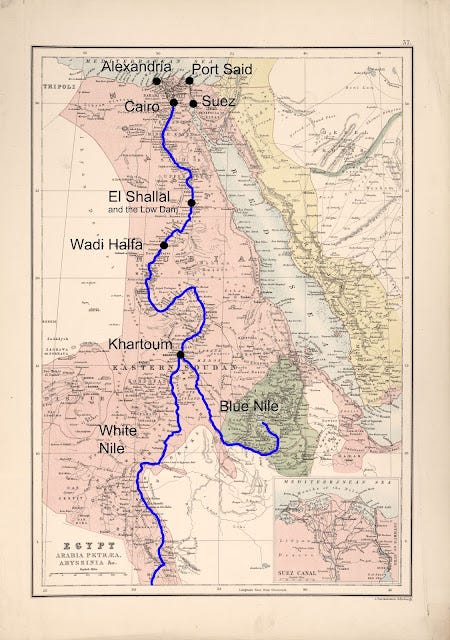

The original 1885 Egypt-Sudan map can be found at this link if you wish to view it at the Library of Congress site.

The map above can give you an idea as to the geography that is dominated by the presence of the River Nile. For most of the land north of Khartoum, anything outside of the Nile valley is dry, hot desert. Most settlements were (and are) close to the river as it travels through Sudan and Egypt.

At the time this map was made, the Suez Canal had been in operation for almost 20 years. Major ports of departure were Alexandria and Port Said for ships on the Mediterranean Sea. It is interesting to note that Shallal is identified as Egyptian, Wadi Halfa as Nubian and Khartoum as Sudanese.

And, as a bit of foreshadowing, the first dam on the Nile, now known as the Low Dam, but known then as the Assuan Dam, was in place to help control the flood/drought cycle of the Nile in Egypt. The article cited below gives excellent details on the construction of this first dam.

The Assuan Dam, Jstor article, H. D. (1913). The Assuan Dam. Journal of the Royal African Society, 12(46), 200-201. Retrieved January 29, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/715871

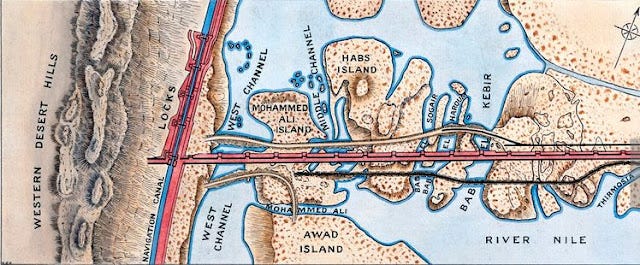

This dam was initially built from 1899 to 1902 and was raised twice - once in 1907-1912 and again 1929-1933. So, by the time this letter was mailed, the Low Dam was... ahem... at its highest. Sorry - I had to.

You might notice the locks to the West of the dam for boat traffic, the rail line would be to the East and Shallal would be northeast of the dam itself. Apparently, the old rail station can be visited - for those who want to see something a bit off the normal tourist path.

The map above is taken from the original 1928 Anglo-Egyptian Sudan map found again on the Library of Congress site. If you look, you can see both the River Nile and the Sudanese rail route from Khartoum to Wadi Halfa. You should take note that the rail line breaks away from the river at the point the Nile turns back southward.

This railway would be the mail route this letter would have taken in 1939, transferring to Egyptian rail north of the border on its way to Shallal (and the Low Dam) and then Cairo. From there, I can only guess as to whether the item went to Alexandria or Suez (and then to Port Said). From that point, we can suppose it went to Brindisi (in Italy), then by land to Ostende (Belgium) and took a ship across the Atlantic from one port or another. With no additional marks or dates, it is impossible to be sure.

But, I've covered those lands with other items before. It's the area around the River Nile that is new to me, so it makes sense that I would want to concentrate there anyway!

Halfa No More

My how things have changed. Wadi Halfa, once so important as a connection between Sudan and Egypt, is no more, covered by the waters (Lake Aswan) created when the High Aswan Dam was put into place in 1971. This dam is just South of the low dam (by Shallal) and the city of Aswan (Assuon) is in that area now.

If you look at the Google Earth picture below, you can see the Aswan Dam in the foreground. The Low Dam is above it in the picture where the two channels of the river meet again.

It is absolutely amazing how descriptions of the new Aswan Dam change when you consider the context of the person(s) looking at it. The Egyptian peoples north of the dam (and down river) benefit from control over a flood/drought cycle that historically caused problems. They focus on the positives of hydroelectric power and consistent river navigation and irrigation systems that this huge dam creates for them. For them, there is a sense of great national pride.

On the other hand, over 100,000 people, mostly Nubians, had to be relocated as Lake Nassar flooded their former homes. Cultural sites, such as Abu Simel and the Temple of Dakka had to be taken apart and moved to avoid destruction. The effort to create a new agricultural project (New Halfa) has been cited as a poorly planned effort. And, environmentalists are not always so sure controlling the Nile has been the best idea.

And I learned all of this simply because I wanted to find Wadi Halfa on a map and I wanted to find Wadi Halfa on a map because I had a single envelope mailed from Khartoum to Maryland.

It has been said that travel is important to help a person learn and grow. But, if you can't travel, buy an envelope with camels for two dollars and see where that takes you. You just might be amazed what you will learn as you take some travels with your mind.

Thank you for joining me yet again for another Postal History Sunday. If you have questions you would like me to address or topics you might enjoy seeing here, please let me know. And, until next time - have a great week!

Want to know more about Sudan stamps and postal history? This site points to several resources.

-------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.