Here, You Pay For it! - Postal History Sunday

Here we are! Must be time for some Postal History Sunday on the Genuine Faux Farm blog! We are now cross-posting our Postal History Sunday posts due to suggestions that our content has sufficient meat that even people who already collect find them interesting.

If you'll recall (and even if you don't), we had a post two Sundays ago that talked about how the clerk or carrier would know whether a letter was fully paid at the point of delivery. The main reason this was important was because it was a common practice to send mail unpaid or partially paid until the middle of the 19th century. As we get into the 1860s, the system was moving steadily towards prepaid mail as the normal process.

It should be no surprise, then, that markings were important to indicate whether an item was paid or not.

India to France

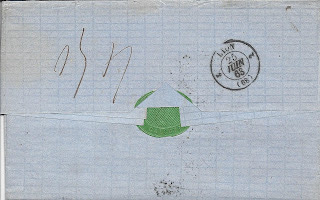

Below is a piece of business correspondence that was sent from Calcutta, India to Lyon, France in 1863.

Let me explain quickly some of the markings that are clearly visible here. The black circular marking (that is upside down) reads "Calcutta India Unpaid," which makes it very clear that this item will have to be paid by the recipient. The red circular markings is a French transit mark that doesn't really play a part in today's story.

The numerical markings, however, do play a part! The "27" in black ink tells the clerk in Lyon that they need to collect 27 decimes from the recipient. And, just as a reminder, 27 decimes is equivalent to 270 centimes. This is essentially the same as a person in the United States saying 270 cents or 27 dimes.

The other numbers (in blue) read "17/3." The seventeen indicates how much this letter weighed in grams (17 grams) and that much weight required triple the base rate of postage (3).

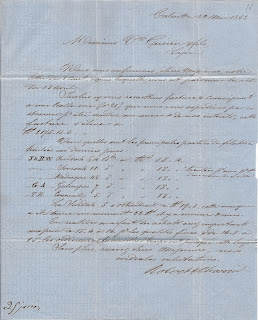

The rate of postage from India to France using British sailing ships to Marseille was 90 centimes for every 7.5 grams of weight. The recipient owed three times that amount or 270 centimes (27 decimes).

Pieces of the Puzzle

Whether you knew it or not, you have just been exposed to one part of how a postal historian checks out an item for consistency and authenticity. While it is not unusual for an item to have odd and unexplained markings that might even contradict, the vast majority of items should show a consistent story. It is really a matter of reading the evidence.

The contents of the letter (click on the picture to see a larger version) clearly show a dateline from Calcutta that is consistent with the marking on the front. The recipient and their location cited in the letter is also a match with the addressee and the Lyon postal marking on the back. The number of days between the dates given with the postmarks for Calcutta, Marseilles, and Lyon are consistent with traveling times in 1863. And, as we showed above, all of the postal rate markings can be explained as being consistent with the rates for mail between these two locations at the time. We can even identify at least one of the ships that carried this letter if we wished to do so!

Thank you for joining us for our Postal History Sunday post. We hope you enjoyed at least a little of it and we shall endeavor to keep helping you to learn something new each week!