Welcome to the 94th entry of Postal History Sunday. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent.

I have been neglecting to remind everybody in recent weeks that they should feel welcome to pour themselves a beverage of their choice and maybe even partake of a snack you like - as long as you keep it away from the paper collectibles (and your keyboard). Everyone is welcome here, whether you have expertise in the topics I share or you are just an interested passer-by.

Let's see if we can all learn something new!

I realize that newspapers and magazines no longer hold the same prominence in our culture as they did even a decade ago, but in the 1860s and 1870s, periodicals required substantial attention from the postal services around the world to get these items from the publisher to their various destinations.

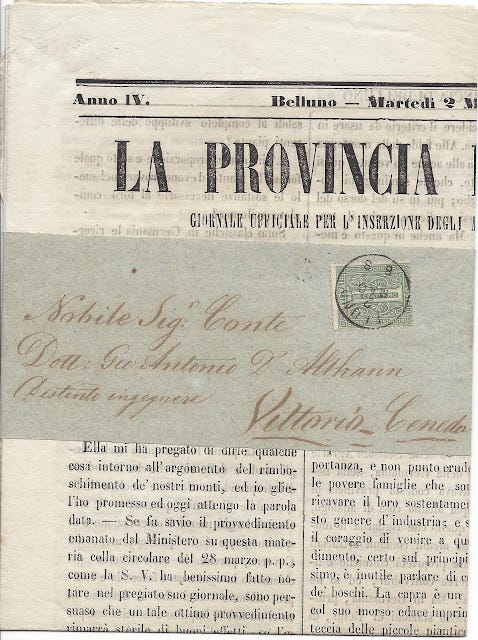

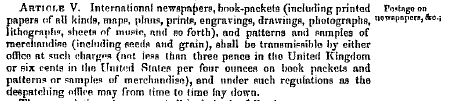

While letter mail was typically the first thing addressed in postal agreements between countries, they could not escape the fact that newspapers and other printed documents required a different type of handling. You certainly don't have to read the blurb shown above. It's just a sample of text from the 1867 convention between the United States and the United Kingdom that mentions newspapers and other "printed matter." I offer that illustration for two reasons. First, to show that newspapers and similar printed matter were often given different postage rates than letter mail. And second, verification that this kind of mailed matter was handled differently.

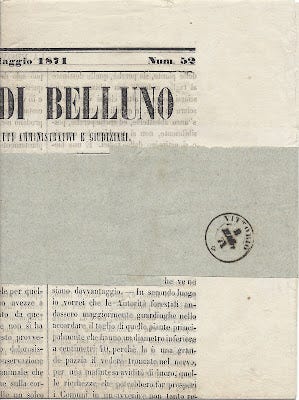

This Belluna, Italy, newspaper dated March 2, 1871, shown above was enclosed by a paper wrapper band that served as a surface for the mailing address and postage. The band also kept the newspaper together and prevented it from inconveniently opening up while it was in transit through the mail services. The Belluno postmark is also dated May 2nd and the newspaper arrived at the Vittorio post office the same day according the marking on the other side of the wrapper.

It almost looks as if this particular newspaper has not been removed from the wrapper band. I suppose I could gently remove it to view the rest and then work carefully to put it back in the wrapper.... but, maybe not. I'm pretty happy with it the way it is. That, and, well, the news probably is a bit dated.

We could speculate as to the reasons why this particular artifact remains in this condition nearly 150 years after publication and mailing. Perhaps this item arrived while the recipient was away and they never did get caught up on the backlog of papers when they got home? I would find it hard to believe that someone would read the paper and then painstakingly fold it up and put it back in the wrapper.

It is a bit more common for a person to find a wrapper without the contents, such as the item shown above. This wrapper band is postmarked on December 12, 1920 in Prague, Czechoslovakia, and is no longer completely intact.

This newspaper postage rate in Czechoslovakia was intended for periodicals published at least four times per year with a maximum weight allowed of 500 grams. This particular rate (5 haler per 100 grams) became effective on October 1, 1920, but there was no 5 haler newspaper stamp available. There were stamps with the 2 haler denomination, so it became common practice to split one of these stamps diagonally to represent 1 haler in newspaper postage. In philately, this is known as a bisect or bisected postage stamp.

If you were paying attention, you might also have noticed that I called these newspaper stamps. These stamps were only intended to pay the postage for items that qualified for the newspaper rates.

Getting back to our original newspaper with the band still intact, we see that it has a 1 centesimo stamp on the wrapper. The stamp shown there was not a specialized newspaper stamp and it served as a regular issue postage stamp, available to show postage was paid for letter mail and newspaper mail alike. The bulk rate for newspapers in the Kingdom of Italy at the time was 1 centesimo per 40 grams (effective January 1, 1863), which explains its use here.

But, it is possible that it actually cost the publisher of this newspaper less than that to get this copy to its customer in Vittorio. Wait… what?

Letter mail in Italy

Let me back up for a second so you can see the whole picture. Above is a piece of letter mail. It cost 15 centesimi to send from Chiavari, Italy to Torino, Italy. The envelope is a personal or business correspondence and it weighed no more than 10 grams.

Letter mail provided great flexibility. You could mail one item and you could seal it up, placing whatever you wanted (within reason) inside the envelope or folded letter - as long as it was flat. The only reason the postal service might open the letter is if they couldn’t find the addressee and it went to the Dead Letter Office to be processed.

You could include a picture, an invoice, paper money, a newspaper clipping, a lock of hair and even, perhaps, the letter you got from Aunt Mable so your cousin could read it too. You just simply had to pay the higher letter mail rate to send it on its way.

Printed matter mail rates

Printed matter mail on the other hand, could not be sealed up. It had to allow the postal workers to be able to check contents to be sure there weren't personal messages or other non-permitted material being snuck in with the mailing! Newspapers were a type of printed matter mail and were typically wrapped up with a paper band. If a postal clerk felt there was a reason to check, they could remove the item and put it back after inspection.

The item above was simply sent as a if it were a folded letter, but there was no wax seal to hold the contents closed. This met the requirements for printed matter and allowed it to qualify for the non-bulk rate in Italy starting in 1863. It was mailed from Torino to Allessandria (both in Italy) for 2 centesimi for an item weighing no more than 40 grams.

Printed matter was 2 centesimi for 40 grams vs 15 centesimi for 10 grams for letter mail.

Ok - I think we see a cost advantage for newspapers, magazines and advertising! But it only makes sense from a business perspective. In the case of a newspaper, people were used to paying 5 to 10 centesimi for a single copy of a newspaper at a newstand. Even if you could pass your costs on to the customer, it was unlikely that readers would pay too much more for the privilege of mailing it to their home address.

Newspapers and Journals

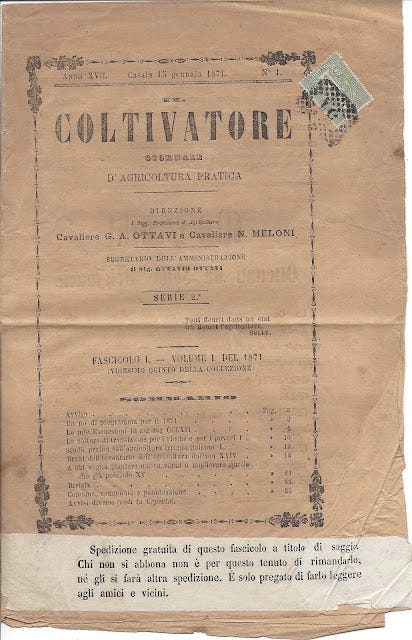

The next item is a sample Farmers' Journal of Agricultural Practices in Italy. The white band at the bottom essentially indicates that this sample is being provided 'gratis' and that the recipient should not delay in sending in for a subscription! At top right is a 1 centesimo stamp that is paying for the mailing of this item from Casale Monferrato. Sadly, the "where it was sent to" portion has been lost. But, it is safe to say it stayed in Italy - and likely landed somewhere in northern Italy.

There was a concessionary rate that provided a discount for newspapers and magazines that pre-sorted their bulk mailing by the destination and the route the items were to take to get to that destination. While this and our first item were mailed under the 1 centesimo rate, we cannot be certain that was the actual cost to the publisher of either of these items because one of these (or both) may have been given this additional discount.

Some bulk mailers paid less than one cent per item if they were regular customers. A weekly newspaper, such as our Belluno newspaper, might qualify for a better rate than a monthly magazine. The thing is, there weren't stamps with denominations for all of these fractions of a centesimo - so they just used the 1 centesimo stamp and the bulk mailer simply paid the bill at the agreed upon rate. In some cases, the stamps were adhered to the newspaper before printing and you can find examples where the newspaper printing goes OVER the stamp.

If you think about it, this makes a great deal of sense for the post offices as well. They can count on consistent business rather than the whims of those who send a single letter at a time. A pre-bundled batch of newspapers to go from Belluno to Vittorio required about as much handling as a single letter from Belluno to Vittorio - until you got to the delivery part, of course. And, yes, they typically weighed more. But, there wasn’t all of the sorting that went into the letter mail process and that counted for something.

When I unfolded the Farmers' Journal item, I found it was a larger piece of paper that was printed as four separate pages on each side. Other than the title page, it was all advertising for agricultural implements, plant stock and other items. At a guess, the actual sample of the journal had been wrapped inside this covering and is no longer part of the whole.

Perhaps someday I will find an actual copy of this Farmers' Journal of Agricultural Practices. Then, I'll brush up my Italian - and learn something new!

Countdown Bonus Material

I asked for some questions that I could respond to in Postal History Sunday, and I actually got a few. Oddly enough, they were all some form or another of "How do you pick your Postal History Sunday topics?"

I feel like I might have answered this somewhere, but I can't figure out where. And, that doesn't matter, because if the question is being asked, there must be some curiosity about it.

First things first - my motivation for most of the topics in Postal History Sunday come from items that happen to reside in my own collection. As I research these pieces of postal history for my own learning, I often find myself motivated to dig in deeper and produce something others might also enjoy. That is usually the root of what starts a particular entry.

I do my best to take note of potential PHS topics by keeping them in a notes file. At present, there are over seventy possible PHS topics in my "future writing" file. Considering this is the 94th PHS, I would say there is potential for many more entries. But having the basic idea for an entry does not write it!

This is where real life enters the picture. Many of these topics could require a significant amount of digging before I could feel ready to write that particular Postal History Sunday. If I do not have the time or motivation to put into those topics, they simply have to wait until I do. For example, last week's topic Friends in Need or the recent blog Two for the Price of One were developed over a period of weeks. On the other hand, a PHS entry like What Caught My Eye is a way I can simply share where I am at with some things I am enjoying without getting in so deep that I will need weeks to put it together.

In other words, I have to adjust my topic selection each week to the available time and energy. Of course, there is more to it than that - but this might give you all a little bit of a peak into how things work in this farmer/writer/postal historian's mind.

I hope everyone has a wonderful day and thank you for joining me on Postal History Sunday. I am always willing to accept constructive feedback and questions that will inform future "Postal History Sundays." You can reach me by using the contact form on this blog page or by submitting a comment below.