This week I’m just going to jump right in! Let the wind take those troubles away for a time while I entertain you with a subject I enjoy. Find a snack and your favorite beverage. Put on your fuzzy slippers and sink into your favorite chair.

Comfy?

I hope so, because it’s time for Postal History Sunday!

Boston to London - 1863

I'm going to start with with a cover (an envelope, folded lettersheet or wrapper) that represents the type of thing that encouraged me to build my knowledge of postal history. We all start somewhere, and it was this sort of item that got me thinking beyond “Oh look, an old stamp on an envelope. That’s pretty neat.”

This letter took a trip from Boston, Massachusetts, and crossed the Atlantic Ocean to London, England. There is a single stamp at the top right that represents 24 cents of postage. It just so happens that the price of mailing a simple letter (a letter that weighed no more than the first weight increment - 1/2 ounce) from the US to England was 24 cents in 1863. The stamp was cancelled (defaced so it could not be used again) with a round grid marking that included the word “PAID” on it in black ink.

As is true with every subject and every hobby, there are some basic terms that help interested persons have useful conversations about the topic. Because Postal History Sunday is intended to be inclusive of people outside of the hobby, but interested in the subject, it is important that I write periodically about the new language these individuals might be encountering.

Today, I am going to put some of these terms in bold and I will do my best to include a description or definition nearby. The good news if this is new or newish to you? There is no exam at the end!

The good news if you already know the language? There’s still some fun postal history to look at and learn from.

It’s a win-win!

This letter was mailed in Boston on, or just prior to January 7, 1863. The American Civil War was raging, with fighting at Stones River (Tennessee) and Fort Hindman (Arkansas). The Emancipation Proclamation had just gone into effect a few days earlier on January 1.

If there were still contents with this envelope, we might read some commentary regarding these events. Yet, as momentous as all that might have been, this was likely just a business letter.

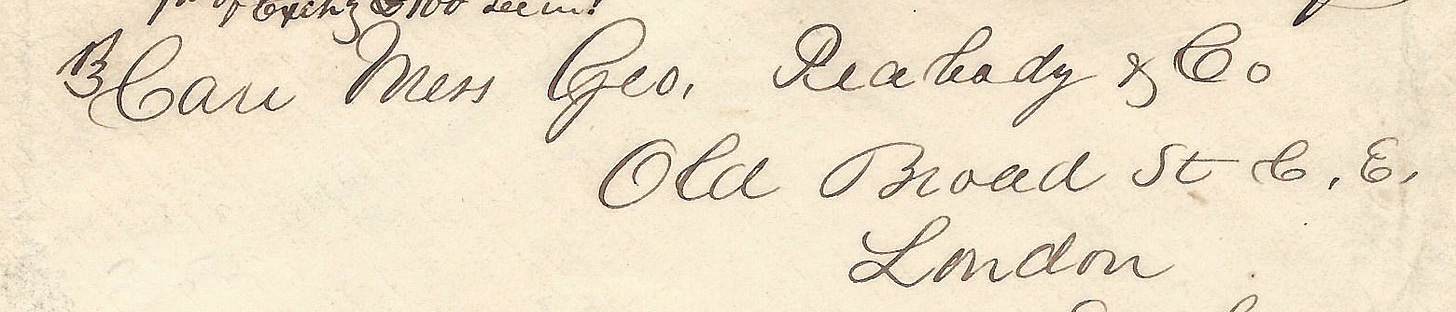

Let’s start by looking at the smaller handwriting at the top-center of the envelope. This was written by the addressee (Charles H Hudson 1833-1922) and it was his way of recording information for future use. This personal docket included the date he received the letter (January 19), the date he sent a reply (January 24), and who sent him this letter (Rideout & Merritt).

I mentioned that I was fairly certain this was a business letter and I have two reasons that bring me to that conclusion. First, “Rideout & Merritt” is likely a reference to a business, bank, or legal firm - but I have not been able to find a match as of yet. And second, Charles H. Hudson wrote an additional docket under his name that references an exchange of money (see above).

While these dockets have nothing to do with the postal aspects of this envelope, it does give us some background as to the purpose of this mail. It also provides us with checks for consistency to be sure all is as it should be here. The red London marking at the right (by the name Hudson) also gives a date of January 19 - that's a match with the docket, so things are lining up nicely!

You might also note that both the London and Boston markings are in red ink and they both include the word "PAID." This is one way post offices communicated that postage was properly paid. So, the pieces fit together. There is a stamp that is the right amount for the postage of the time. There are two markings that show that both the US and British postal services saw this letter as paid to the destination. And, the dates on the various postal markings line up with expected travel times and dockets.

When all of these things fit together like this, we can be very certain that we are reading the cover correctly.

Let's look more closely at the Boston postmark or postal marking. There is actually more information that I can extract just by knowing a bit about yet another “language.” This is the language postal clerks used to communicate in the middle 1800s.

This particular postal marking is known as an exchange marking applied at an exchange office. Exchange offices were post offices that handled the transfer of mail to and from other postal systems. Boston served as one exchange office between the United States and the United Kingdom. On the UK side of things, London was an exchange office with the US.

Let’s take a moment and break down the exchange marking:

Br. Pkt

This is an abbreviation for "British Packet." A packet was a steamship that carried the mail across the Atlantic Ocean. Some mail packet companies had contracts to carry the mail for the United States (an "American Packet") and some had contracts to carry mail for the United Kingdom (a "British Packet"). This marking actually gives me a chance to identify the ship that carried this letter from Boston and across the Atlantic!

On January 7, 1863 the Europa left Boston. This ship was owned by the British & North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company - a shipping line that is often referred to as the Cunard Line (for its founder Samuel Cunard). It arrived at Queenstown, Ireland on January 17 and probably went on to Liverpool the next day.

19 Paid

Well, we all understand the "Paid" part. But, what's with the "19?" Didn't we say that it cost 24 cents to mail this letter?

Indeed, we did! And, yes, it DID cost 24 cents. The issue is that the United States provided some of the mail service and the British provided the rest of the mail service to get from point A to point B. At this point in history, it was important to account for how much of the 24 cents went to each postal system so each could properly cover their expenses.

Five cents covered the mail services within the United States. Sixteen cents paid for the Atlantic voyage. Three cents covered mail service in the United Kingdom. Since the British had the contract with the Cunard Line, they had to pay the shipping company. So, the British needed 16 cents for that and 3 more cents for their own mail services for a total of 19 cents.

This marking simply says the United States must pay 19 of the 24 cents they collected in postage to the British Post Office. The US Post Office kept the remaining five cents.

I can also determine that Charles H. Hudson, a civil engineer and Harvard grad, was traveling in Europe and not a resident. Perhaps he was traveling with Frances Hudson (nee Nichols), a Bostonian whom he had married in the prior year? Hudson helped build bridges and railroads during his career and lived with Frances in Lexington, Massachusettes, until they moved to Knoxville, Tennessee in 1885.

George Peabody & Co was the premiere American bank in London in the 1860s. Financial institutions, such as Peabody’s, could provide letters of credit for traveling Americans. In addition to financial services, they also provided mail holding and forwarding services for travelers while the account was open. Postal historians often, unsurprisingly, focus on the handling of the mail and refer to businesses such as Geo. Peabody as a mail forwarding agent.

New York to Tampico - 1918

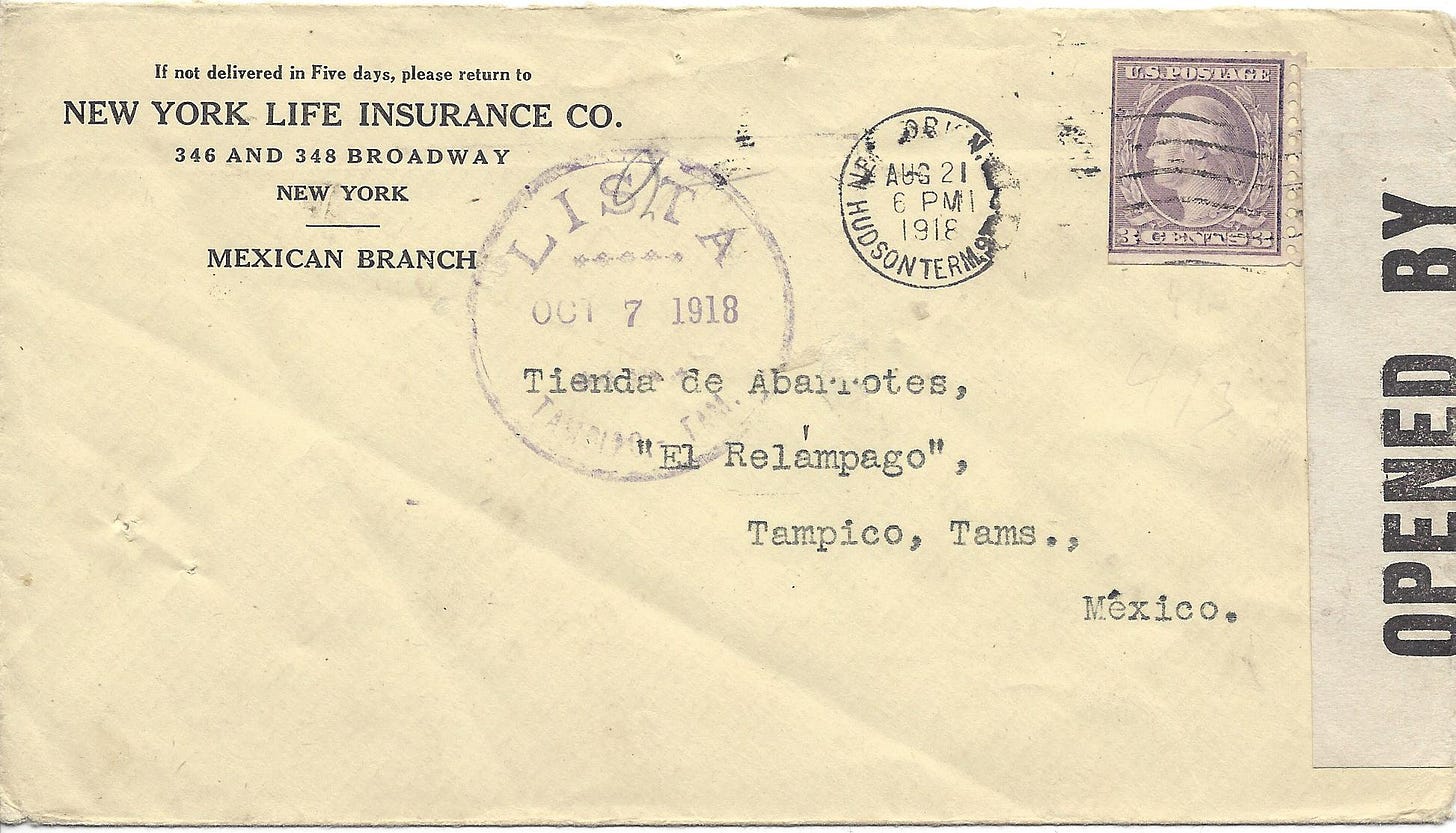

Below is a much more recent letter. The New York Life Insurance Company sent this envelope from their offices in New York for their "Mexican Branch" to a grocery store company (tienda de abarrotes) named "El Relampago" in Tampico, Mexico. The cover was sent from New York on August 21, 1918 and the cost to mail a simple letter from New York to Mexico was 3 cents.

Happily, the 3 cent postage stamp covered the cost properly and the stamp was cancelled with some wavy lines. The CDS (City Date Stamp) postmark tells us the letter was mailed from the Hudson Terminal Station in New York City at 6 PM.

And yes, I picked this cover because it has the name “Hudson” on it - just like the first item. Just don’t expect me to do that with the next item after this. I’m only good for one of these today!

World War I still had a couple more months to go until Armistice Day (Nov 11) when Germany surrendered. The postage rate had been temporarily increased from 2 cents to 3 cents to help finance the war effort. Meanwhile, the second wave of the Spanish Flu pandemic was just getting underway - fueled by troop movements (among other things).

The tape that reads "Opened By" at the right of this envelope shows that this letter was opened by a censor prior to its delivery in Tampico. Censor tape and censor markings are a field that some postal historians study in great depth. I will admit that I am not one of those persons, in part because it was not used in my primary period of knowledge (1850 - 1875).

As an interesting side note, I learned that in addition to redacting content related to military actions, they also removed references to the ongoing pandemica. The feeling was that dissemination of information on the illness would give rise to panic. Public health officials down-played the illness, suggesting that taking appropriate precautions would be sufficient to stay healthy. As a result, media reporting of the pandemic does not always reflect the seriousness of actual events until the illness receded.

This summary article by Christopher Klein provides a good description of the effects of the Spanish Flu:

[P]atients who arrived with coughs, sore throats and high fevers “very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen.” Within hours, mahogany spots dotted soldiers’ cheeks before their faces turned such a dark shade of blue or purple from a lack of oxygen in their blood that Grist reported it became “hard to distinguish the colored men from the white.” Patients bled from their noses and ears, gasped for air as fluid filled their lungs and eventually suffocated from their own mucus and blood.

After taking the lives of 195,000 Americans in October 1918 - the month this letter traveled to Mexico (where the illness was also peaking) - it would go on to claim the lives of as many as 50 million people globally (total population was estimated to be 2 billion).

This cover also has another marking that was applied in Tampico. The marking reads "Lista Oct 7, 1918." Clearly, the letter had been in the Tampico post office for a while because there is no reason a letter mailed in mid-August should take much more than a week to get to its destination.

By October, no one had come to claim this mail. It is important to note that there is no street address given on this envelope. So, it was expected that the recipient would come to pick up mail at the post office. But when no one did, the post office advertised the letter in a local paper in hopes that the recipient would see that they had mail.

Advertised mail was a common practice for mail sent as a "general delivery" item. General delivery, also known as "poste restante" in Europe, meant the letter was sent to the post office and not delivered to the recipient by a carrier. It was the recipient's responsibility to come to the post office and check to see if they had any mail.

Le Havre to Philadelphia - 1873

Big changes in postal processes can often be attributed to one or more historical events that led to adjustments in mail handling. For example, censor tape was introduced to reseal envelopes that had been inspected to check for content that should be removed during World War I.

We can detect another such example with mail between the United States and France in 1870. Letter mail handling was fairly consistent from 1857 to 1870, but once we get to 1870, letters look quite a bit different.

Sure enough, there is a significant historical event that plays a role in this change. France lost the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, which included the Siege of Paris in early 1871.

It would be incorrect to say that the war was the sole cause for the change in how mail with the United States was handled. But, it would be accurate to say that the conditions that led to that war also contributed to the postal changes.

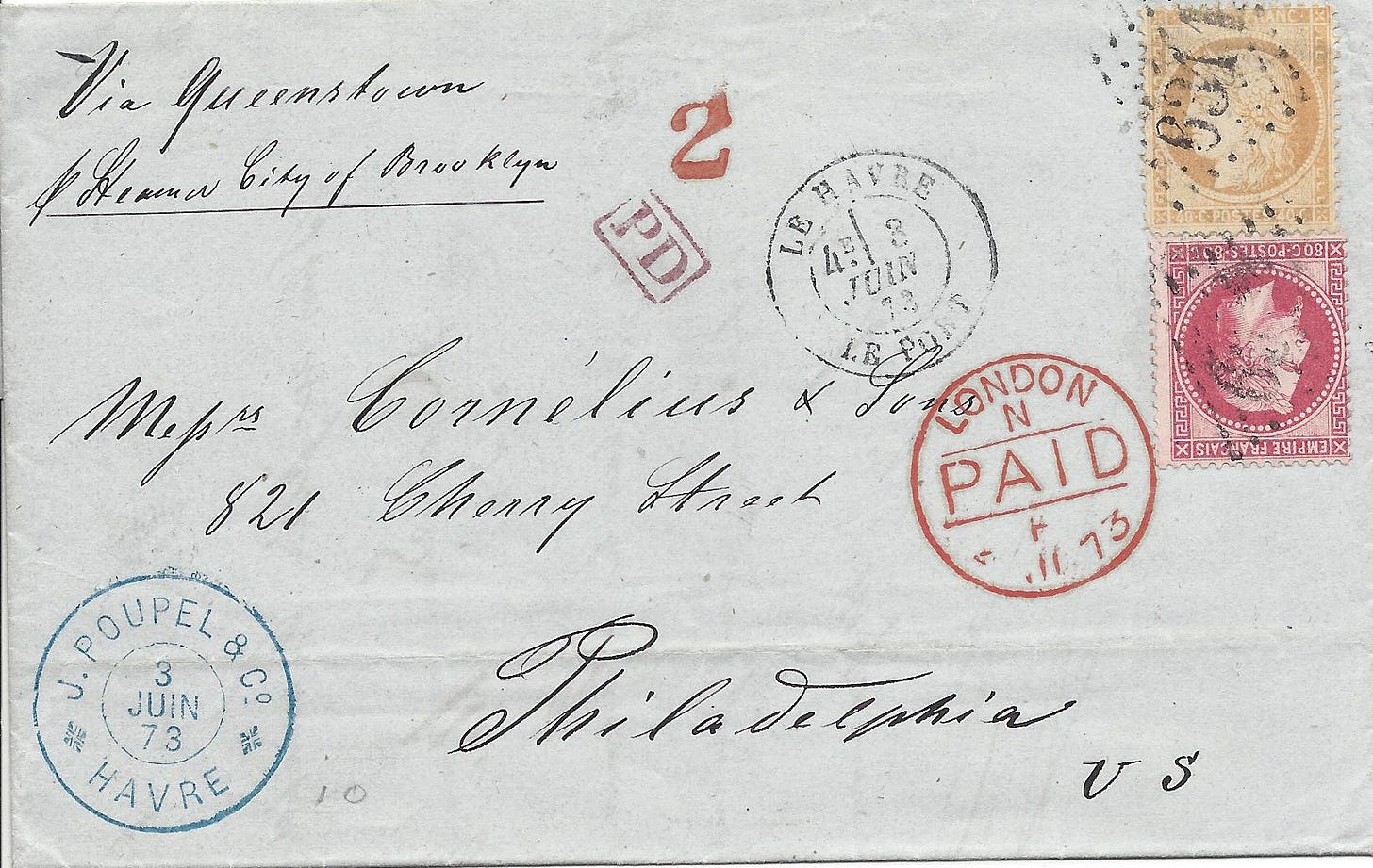

First, we can exercise our docket reading once again. The top left reads "Via Queenstown, p. Steamer City of Brooklyn." It just so happens the City of Brooklyn was scheduled to be in port at Queenstown on June 6. This ship was owned by the Liverpool, New York & Philadelphia Steam Ship Company, founded by William Inman. I suspect you see a pattern here. People have historically looked for shortcuts when referencing things - so this company was routinely known as the Inman Line. The ship would arrive in New York on June 16.

The words around the circle of this marking read: "Le Havre Le Port."

Le Havre would be the city in France and Le Port would be the post office branch that received this item for mailing. And if you look at the words inside the circle, you will likely recognize the date: June 3, 1873. You might, however, be uncertain as to what the "4E" might reference. Larger post offices had multiple mail distribution and departure time each day. This would be the 4th collection period of the day on June 3. This was apparently early enough for this item to get to London on June 4 by a channel steamship.

The big difference that I see, as a postal historian, is that there were actually multiple postage rate options between France and the US after the postal convention between the two countries ended on December 31, 1869. Prior to that the postage was 80 centimes per 1/4 ounce. Now, the postage rate differed depending on which route you took to get to your destination.

A new postal convention with the United States was probably not France’s biggest concerns in the late 1860s and early 1870s. In fact, postal authorities in Paris were just trying to figure out how to get mail past the Prussians during the Siege.

Holland to France - 1836

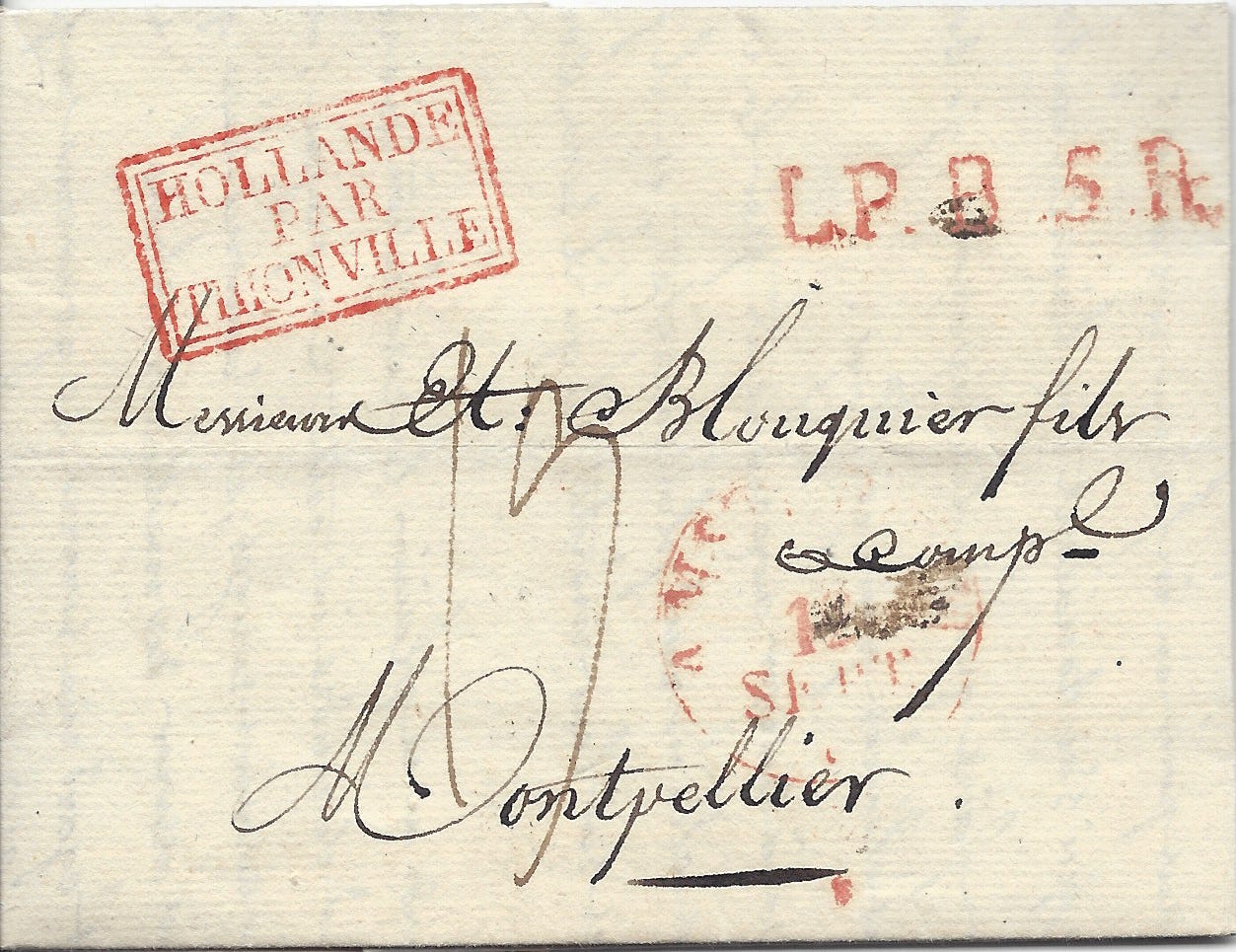

Now we'll take you back before there were postage stamps! Here is a letter from Amsterdam to Montpellier, France in September of 1836. At this point, the Netherlands was still trying to hold on to Belgium, despite the latter's proclamation that it was independent in 1830. This conflict would not be settled until 1839.

At this point in time, the cost of postage for a letter was calculated as much by distance as it was by weight (or sometimes the number of sheets in a letter). Most letters were sent unpaid or partially paid, with the expectation that the recipient would pay for the honor of receiving the item.

One of the difficult things about postal history of the 1800s is that numbers don't always look like the numbers you and I are used to. One must remember that postal clerks were often handling A LOT of mail and we have to expect some shorthand. What was important is that they and their compatriots understood each other. It did not matter if the general public understood, nor were they thinking about a farmer (who likes postal history) nearly 200 years later looking to understand those markings.

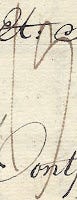

What you see above is a "19." This represents 19 decimes or 1 franc, 90 centimes, which was the amount the recipient was going to pay in order to receive the letter. That is a fair amount of money considering the cost would be reduced to 60 centimes when we get to the 1860s.

The postal rate calculation is aided, in part, by this marking that appears at the top right of the folded letter.

L.P.B.5.R. = Les Pays Bas 5th Rayon

The French know the Netherlands as "Pays-Bas" or "Les Pays-Bas," which is literally translated as "Low Country(ies)." This shouldn't sound odd since the English refer to it as "the Netherlands" with "nether" being defined as "lower in position." You could also, of course, refer to it as Holland.

The 5th rayon refers to a region or a distance within Les Pays Bas. The 5th region was the furthest from France and required the most postage to cover the distance from Amsterdam to Thionville in France. Then, French postage would be added for the distance from Thionville to Montpellier.

As rail transportation became more common, the distance component began disappearing from the calculation of postage rates. But the process of railway development in Europe was only just getting started at the time this letter was mailed.

The result? Postal historians have the opportunity to look at these old letters and try to puzzle out the language postal clerks used in the 1830s.

Thank you again for joining me for Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.