Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

If you are visiting Postal History Sunday for the first time or are fairly new to it, this seems like a good time to do an introduction. For those of you who have been reading PHS for some time, you know what to do - get yourself settled in!

Postal History Sunday is a blog (or a newsletter as Substack likes to call them) by a vegetable and poultry farmer (Rob Faux) who just happens to find postal history fascinating. This project started in mid-2020 as a way to reach out to others during the pandemic and has not missed a Sunday since the tail end of August of 2020. If you would like to learn more about PHS, I recommend checking out the About page. If you want to read older PHS, you can visit the Archive. And, if you want to learn more about me and the Genuine Faux Farm, you can go here.

All are welcome here! These blogs are meant to be accessible to people of all backgrounds, whether they have no intention to collect postal history, might wish to start doing so, or already have a collection of their own. So let's get down to business and let the farmer share something he enjoys - and maybe we'll all learn something new.

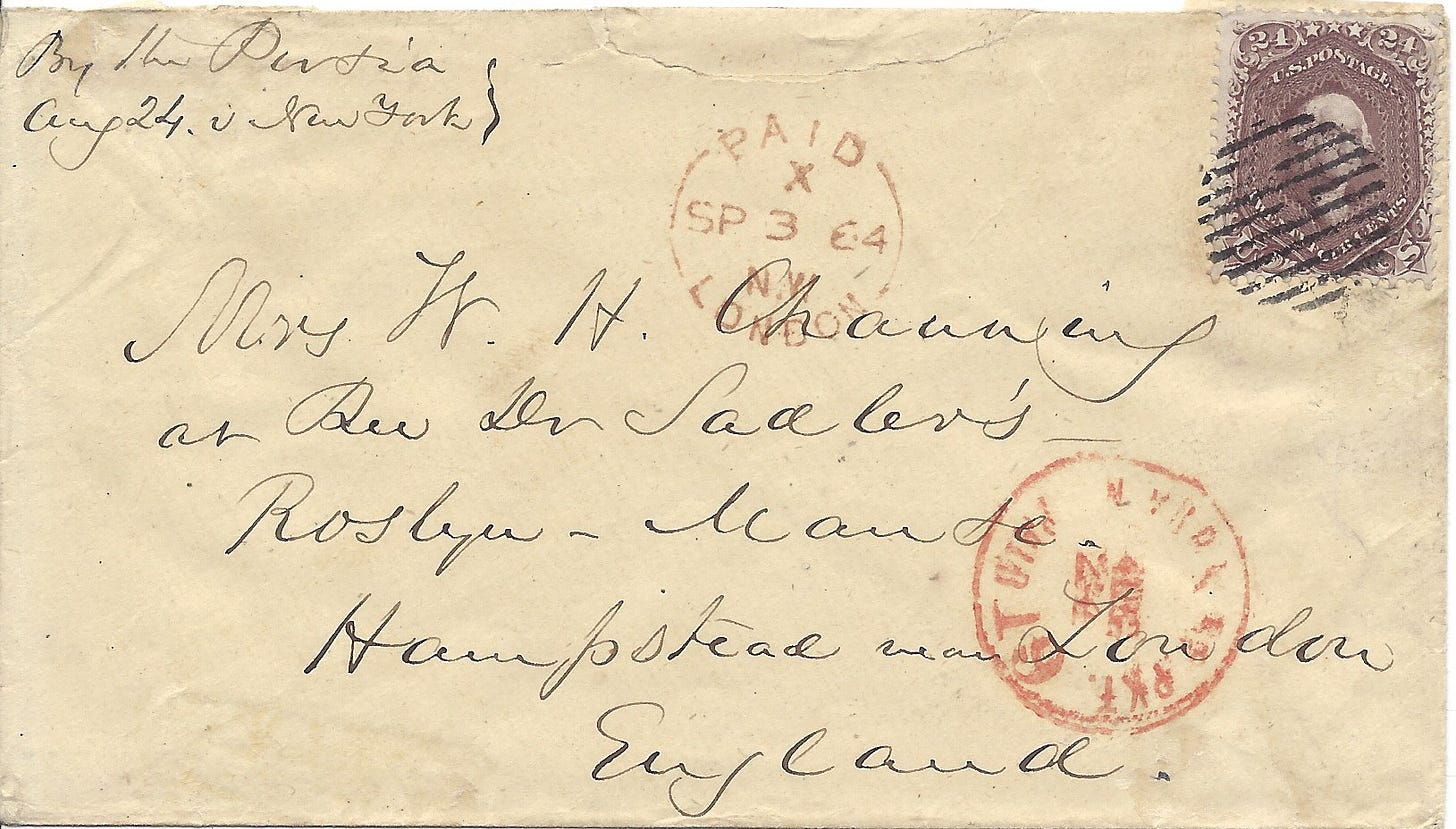

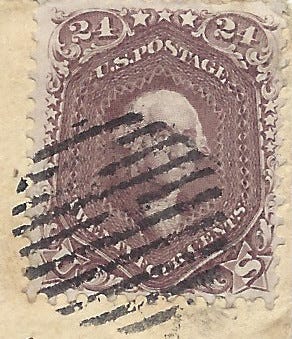

When it comes to an item of postal history, I have found that I can decide for myself how much depth of understanding I require to be satisfied. For example, if I were looking for a cover that shows the postage rate for a simple letter sent from the US to England in 1864, the envelope shown below would do just fine! It has a 24-cent stamp from the 1861 US postage stamp series that properly paid the 24 cent rate for a letter weighing no more than 1/2 ounce. The postmarks are clear enough to show that it went through New York and ended up in London. I can even tell you, based on those postal markings that the letter took ten days to get from New York to London.

All of the information I have given up to this point could be sufficient to make a person happy. And, all of the information shown above is factually correct. But, is it enough?

Well, that much information was enough for me at one point in time, but curiosity has a way of getting me into trouble. Or, at least, my curiosity has a way of encouraging me to look beyond the basics. I think that is healthy, but a person needs to be prepared to curb the imagination and stick with the facts as a cover presents them.

This envelope no longer has its contents, so we can't know for certain who it came from. The earliest postmark is the August 24 exchange marking at the bottom right that was applied in the New York foreign mail office. While it might be tempting to make the claim that the letter was mailed on the 24th, we cannot be entirely certain of this since the New York exchange office typically used the departure date of the mail steamship - NOT the date the letter arrived at the post office.

In other words - this item could have been at the New York exchange office on August 23 (for example), but the clerk still put an August 24 date on the letter if that was the date for the departure of the ship this letter was to leave on.

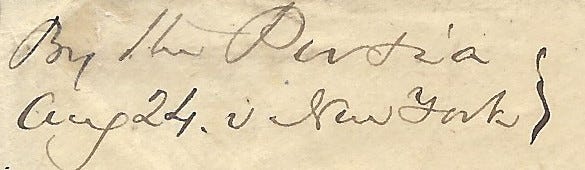

The sender of this letter was apparently quite aware of the mail sailing schedule, as they placed a docket at the top left that read "by the Persia, August 24 v(ia) New York." In fact, the Persia did depart New York on that date in 1864 and it arrived at Queenstown (Cobh, Ireland) on September 2. At that point, the mailbag containing this letter was taken off of the ship and placed on a train that went to Kingston (near Dublin), Ireland.

From there the letter crossed from Ireland to Holyhead on another steamship and continued by train from Holyhead to London. These mail trains ran both night and day and this letter traveled on the night train since the London arrival marking is dated September 3 (the day after the Persia arrived in Ireland).

As I mentioned earlier, the cost of a simple letter in 1864 that was sent from the United States to anywhere in the United Kingdom was 24 cents for an item weighing no more than 1/2 ounce. This postage rate was set by a treaty between the US and the United Kingdom that went into effect in 1849 and continued until the end of 1867. The volume of mail using this rate was significant enough to warrant a postage stamp with the 24 cent denomination and the US issued a stamp for that amount beginning in 1860. This particular postage stamp design was first issued in August of 1861 and remained in use through 1868.

To sum up - this letter was fully prepaid by the 24 cent stamp and nothing more would be owed by the recipient.

At this point, I suspect most people would be very satisfied that I have uncovered plenty of details regarding this particular cover. Even I was pleased with that much information, until…

Finding Mrs. Channing

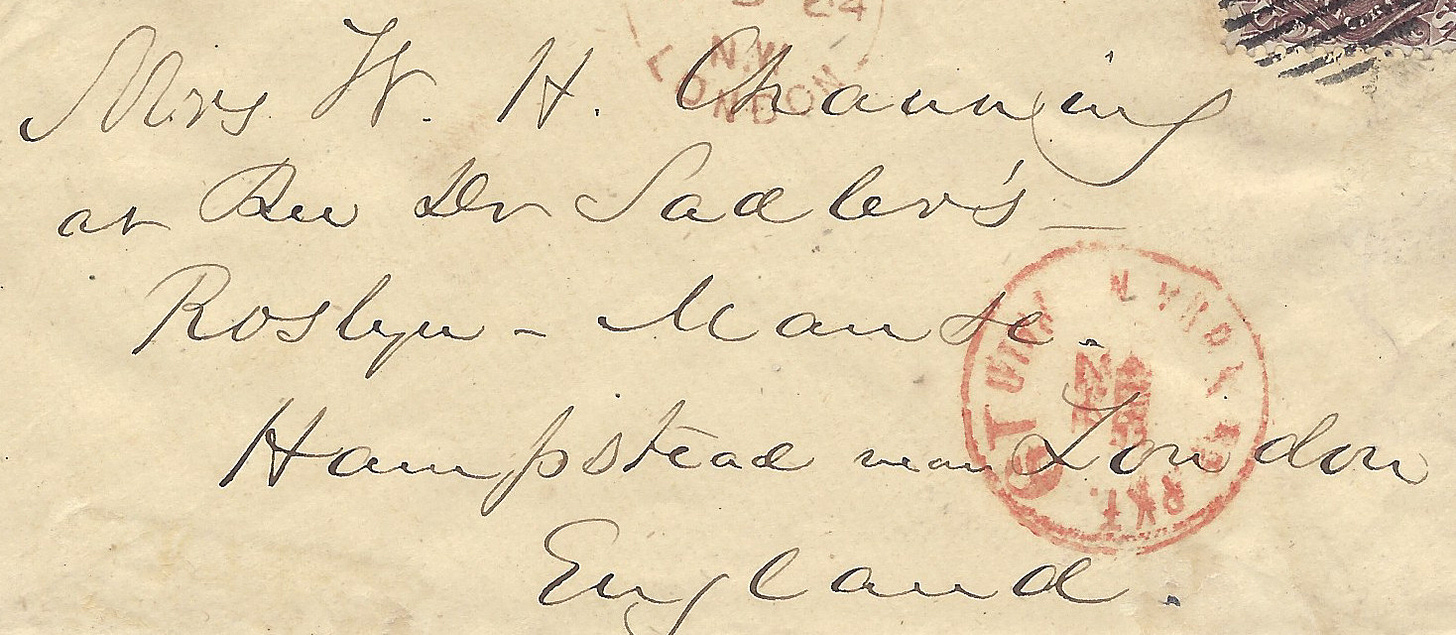

I was working on a Postal History Sunday article where I wanted to use a 24-cent cover to illustrate that a precise address on a piece of letter mail typically indicated that a delivery to that address was expected by a letter carrier. This cover appears to have a street address on the address panel (the area on the envelope that shows the destination address). So, it seemed to me that it was a good candidate.

Here is what I THOUGHT this address panel read initially:

Mrs. W.H. Channing at Rue de Saalers, Roslyn Manse, Hampstead near London, England

This address armed me with several pieces of information that might allow me to find an actual location on the map. That, in turn, could help me identify the recipient. The easy part, of course, is "London, England," but that hardly narrowed the search.

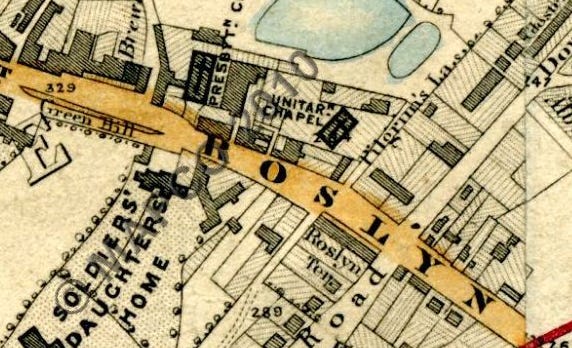

I was able to refine my search by focusing on "Roslyn Manse" and "Hampstead." I did some searching for period maps and found Stanford's Library Map of London for 1864, where we find this rendering of the area that is Hampstead - a very affluent area.

(Some of you might notice the name Sir Rowland Hill at the bottom right. If the name means nothing to you, we'll give you a little information at the end.)

If you click on the map image shown above and look towards the bottom left, you will find Roslyn House. It was built in the 1720s and became known as Roslyn (or Rosslyn) House in 1793 when the first Earl of Roslyn, Alexander Wedderburn took possession of the property. This site actually provides us with an opportunity to view different London maps of the same area over time, so we can see how the area has changed. And, for those who would like to read more about the history of Rosslyn Hill, I will send you to Old and New London: Volume 5. Originally published by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878 - check pages 483-494.

It was at this point that I felt that, maybe, I had found where Mrs. W.H. Channing received this letter. After all, house and manse were close enough to the same thing. So, the next step was to check out the rest of the address as I was reading it.

Where is Rue de Saaler's?

There is always temptation when you find something that looks like a match to believe you've got it all figured out and there is no reason to keep digging. But, I had a problem with the conclusion that the letter's destination was Roslyn House. I could not find "Rue de Saalers" on this map! With a map this detailed, surely a road next to Roslyn House would be a match, wouldn’t it?

For those who do not know "rue" is French for "street" and it is not entirely unknown to find a letter to England from the United States that might use the French version of a street address. But then again, it isn’t all that common either. That should have been a clue to me that something wasn’t quite right. In my defense, I had been working with some French postal history and maybe my brain was unduly influenced by that.

Regardless, you would think if the writer would include a street name that there should be evidence of that street SOMEWHERE on the map, right? I went backwards and forwards in time, looking at maps from different periods and could not find a street with this, or a similar, name.

So, let's look at that address again.

You know. At second glance, it isn’t Saalers. It says Sadler's. The second "a" is a short "d" - kind of like the one found in Hampstead. Ok. That's great.

Except I didn't find a "Sadler's Street" either.

Looking from another angle

Well, maybe the person who addressed the envelope made a mistake with the address. It is certainly possible. But, that solution did not feel right to me. So, I looked at it from the perspective of the recipient. Who was Mrs. W.H. Channing?

A little searching turned up this article (link is no longer active) put together by Dr. Anne Woodlief for a graduate class on American Transcendentalism. William Henry Channing was born in Boston in 1810 and was a Unitarian Minister for various congregations throughout his life, including some time spent in Liverpool, England, from 1854 until the Civil War, at which time he returned to the United States. According to Woodlief's material (viewed Dec 29, 2021):

"He was the chaplain of Congress, labored in the hospitals, gave much of his time to the work of the Sanitary Commission and the Freedman's Bureau, and did valiant service in the cause of the union and for emancipation. He returned to England at the close of the war, preached for a time in London, and also in other places."

While there certainly could be many other W.H. Channings in the world at that time - this biography seemed to fit for this letter. So, why would Mrs. Channing be at Roslyn House? It made sense that she may have stayed behind in England while her husband returned to work during the war - but it seemed like a connection to this particular residence needed to be found.

This is where Sadler comes in

This is where I started putting things together. Let's look at the map again. And to help you out, let me show you what I remembered seeing that was going to put it all together.

On Roslyn Hill there was a Unitarian Chapel and it happens that the home occupied by a Presbyterian minister is a "manse." Prior to this point in my life, I had heard of parish house, parsonage, clergy house and rectory - but not manse. So, of course, I initially made the connection of "manse" to large house or mansion. It was only partly by happenstance that there actually WAS a Roslyn House in Hampstead to lead me astray.

It turns out Thomas Sadler was a Unitarian minister who served at Roslyn Hill from 1846 until his death in 1891. He oversaw the construction of the new chapel that opened in 1862. Like Channing, he is also credited with several written Unitarian works, though he was not nearly as prolific nor as well known. And, Thomas Sadler lived at Roslyn Manse, the clergyman's house.

It certainly does makes sense that Mrs. Channing might be the guest of another Unitarian minister at the time that her husband would return to serve as the chaplain of Congress during the war.

And now we actually KNOW what was written on the address panel:

"Mrs. W. H. Channing, at Rev. Dr. Sadler's, Roslyn Manse, Hampstead near London, England"

The clues were likely there all along and they seem much more obvious now that we know what we are looking for. If this had read "rue de Sadler's" we would perhaps see "Rue" capitalized, but “de” would not be capitalized as it is here. And, I was bothered from the start that the road had an apostrophe - which makes more sense once we know "Sadler's” references a person. And why would a person bother with the word "at" before a road name anyway?

And, yes, it is highly likely that the mail carrier took this letter to Roslyn Manse so Mrs. W. H. Channing could receive her mail sent care of the good Reverend Doctor Sadler.

There is your story for this fine Sunday (or whatever day you end up reading this). This is just an illustration of how easy it is for any of us to err with respect to the details on a piece of postal history. We can easily misread what is written and we can fail to recognize that some words do not have the same meanings now as they did at the time when the letter was written. This is one reason why I am not always satisfied with leaving parts of a cover unexplained. If we choose to look at only a subset of the details we can be led astray and to conclusions that are simply wrong.

Bonus Material!

Sir Rowland Hill is a name that happens to be known by many postal historians and philatelists as he is often credited with the invention of the postage stamp. But, more importantly, Hill was on the forefront of postal reforms that led to cheaper postage, making it possible for more of the populace to avail themselves of this service. He wrote "Post Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability," and the United Kingdom implemented those reforms in 1840. I have provide the link to the 3rd edition of this work published in 1837.

If you are interested in a very short bio and a portrait of Hill, you will find them at this location in the National Portrait Gallery.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Your PHS posts are endlessly fascinating & engrossing.

Sometimes the key won't open the lock on the first try! My parents had an expression when I failed at a simple task, "Well - you weren't holding your mouth right!" And so, "Ru De Saaler's" becomes "Rev Dr Sadler's". Some amazing detective work this Sunday morning, Rob!