Letter Mail from the US to Switzerland in the 1860's

Post last edited: Nov 13, 2019

Status: Advanced Draft

Letter mail between countries prior to the General Postal Union (1875) relied on postal conventions that were established by treaty between nations. Needless to say, not every pair of sovereign states had a direct agreement that dictated how mail would be exchanged. Mail between nations that did not have a direct agreement relied on a chain of postal conventions that connected them. In most cases, that chain was created by finding one intermediary that had independent agreements with both of the states in question. Mail that does not originate within a country and also does not reach its destination within that nation is said to be in transit through its postal system.

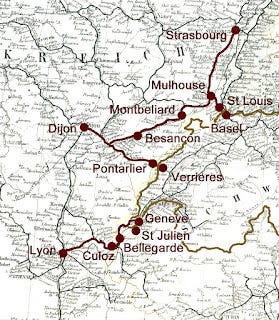

Case in point, Switzerland and the United States had no postal convention in place until 1868. This makes sense for several reasons, but the most obvious is that there was no way mail could be carried between the US and Switzerland without transiting a third nation. A quick look at a map will show you that Switzerland has no direct access to ocean transport. The Swiss would have to travel through one of Italy, Austria, France, some of the German States (Wurttemburg, Bavaria, etc) and possibly have stops in Belgium or other nations along the way. Any postal agreement between Switzerland and the United States would require connections to other agreements just to manage the transit through some or all of these independent states.

In 1860, the United States maintained postal agreements with the French, Prussian, Bremen and Hamburg systems. It was also possible to send mail to the British mail services to be sent on through whatever routes were available between England and Switzerland.

French Mail to Switzerland

The French mail system provided the United States with services to Switzerland from April of 1857 until December of 1869 at a cost of 21 cents per quarter ounce (7.5 grams) for letter mail. Much of this postal convention can be viewed in the post titled "Postal Convention: France & the United States 1857." Mail would travel by trans-Atlantic steamer from New York, Boston, Portland (Maine) and Quebec bound for locations in England, France and Germany, depending on which steamship line carried the piece of mail in question. Items bound for France would typically sail directly to France or travel via Britain. The entry point in France was most often Calais (or the rail line from Calais to Paris), but it could also be locations such as Havre and Brest. If you would like more detail on how mail got to France during this period, the post titled "Letter Mail from the US to France in the 1860's" will provide you with that information.

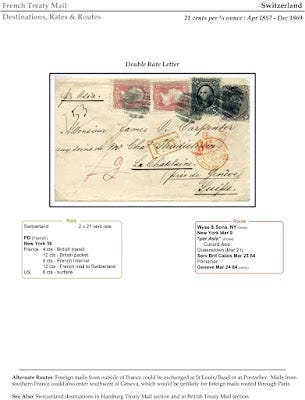

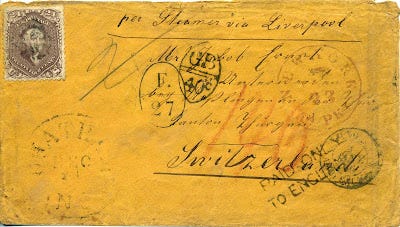

Figure 1, click to view larger version of images

The rail systems in France were developing rapidly from the 1840's and through the 1860's. Foreign mail was carried by train to Switzerland via three primary border crossings. There were other crossings that typically handled local mail and were unlikely to carry foreign mail, though it is technically possible. Mail could enter Switzerland in the North at Basel, West at Pontarlier and South at Geneva. The route was chosen based on a combination of train schedules and location of the destination relative to the border crossing. The hope was to send the mail via the route that would see the quickest delivery time.

Figure 2 - border region of France and Switzerland

The envelope shown in Figures 1 and 3 is presumed to have gone via Pontarlier based on some incomplete train schedule data that I have located. It is entirely possible that this is incorrect and I hope to be able to decipher the route more fully in the future. The 1864 year date makes it possible that the entry was in the South depending on the completion dates of some of the rail lines in the Jura mountains.

A prior post on this blog highlights the letter mail between France and Switzerland and provides some additional information regarding rail travel between the two nations. The difficulty is that letters transiting France from the United States were not provided some of the same markings seen on Swiss/French mail. As a result, we tend to get fewer clues from the piece to isolate the route once it was in Europe.

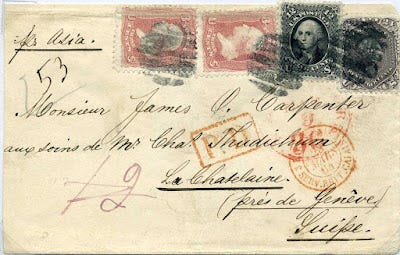

Figure 3 - Double the 21 cent French Mail rate from the United States to Switzerland

The letter shown above appears to have been sent from New York City to La Chatelaine near Geneva, Switzerland. The portion of the address panel that reads "pres de Geneve"* simply indicates that this is La Chatelaine "near" or "next to" Geneva. The larger, red circular marking was applied in New York, dated March 9 and indicates that 36 cents of the 42 cents collected in postage is to be passed to France to cover postal expenses not rendered by the United States postal system. The French then passed money to the British and Swiss postal systems.

* my apologies for my failure to use proper accents/characters. I will try to clean this up at a later point in time. Silly American.

The breakdown of the postage rate is often not as simple as saying 6 US cents go here and 12 US cents go there. What can be said entirely accurately is that 42 US cents were collected via US postage. Thirty-six of those US cents were passed to the French postal system. An amount roughly equivalent to 16 US cents was sent in French centimes (probably 80 centimes) to the English to cover the sea passage and the transit on British rail from Liverpool and the English Channel crossing. This left 20 US cents, which is in the neighborhood of 1 franc in French currency, to cover transit through France and the cost of mail in Switzerland to deliver to the recipient.

For the sake of argument, mail from France to Switzerland cost 40 centimes (French) per 1/4 ounce. So, this double weight letter would have cost 80 centimes if it originated in France. This rate was split at 50 centimes for French postage and 30 centimes for Swiss postage. So, it is not unreasonable to speculate that 30 centimes (about 6 US cents) was passed on to Switzerland to cover their postage costs.

In the end, the breakdown could look like this:

The US retains 6 cents of postage

France receives 36 cents from the US

Britain receives 80 centimes from France

Britain pays 6 pence to the Cunard Line for trans-Atlantic service

Britain retains 2 pence for internal rail service and the English channel crossing.

France passes 30 centimes to Switzerland (equal to 30 rappen) for their internal mail service

France retains 70 centimes for their internal mail services

All of these amounts are estimations because I am not currently willing to work out all of the details as to actual exchange numbers between all of the players. involved. For this excercise, I am operating under a simple 5 French centime to 1 US cent conversion, though the actual rate was 5.26 centimes per 1 US cent. In the end, that conversion number matters less because the actual postage breakdown numbers are filtered through three sets of postal treaties; the treaty between the US and France, the treaty between France and Britain and the treaty between France and Switzerland. In the end, it appears that the French make out like bandits since their internal rate was 40 centimes for a letter weighing 10 to 20 grams.

There is still plenty that can be explored regarding this cover. If you look, you will notice several manuscript markings. A pencil "2" notation certainly was applied to indicate that this is a double weight letter. I have no idea whether the "53" is a postal marking or a filing docket placed on the envelope after it was received. The "12" has all of the hallmarks of a postal marking, but I am currently at a loss regarding its importance. It is crossed out which may mean it was placed on the cover in error OR it shows an amount passed and then recognized as passed and crossed out. In that latter case, crossing out the amount makes it clear that it is not a due amount for the recipient.

Prussian Closed Mail to Switzerland

The Prussian mail system provided mail services for the United States to Switzerland starting in 1852 until December of 1867 when the Prussian system was superseded by the North German Union mails (essentially the Prussian mails with other German mail systems consolidated with it - a topic all its own). The postage rate was 35 cents per half ounce (15 grams) until May of 1863 when the rate was reduced to 33 cents. *

* This may be, in part because Baden's rate drops from 30 cents to 28 cents in May of 1863 to align it with the rest of the German-Austrian Postal Union. Also a topic worthy of more discussion.

Figure 4 - Switzerland via Prussian Closed Mail

Mail to the Prussian system typically traveled through Belgium after a stop in England. Mailbags would enter the Prussian mail system officially at Aachen (Aix la Chapelle) or on the mobile post office between Verviers and Coeln. Belgium and Prussia featured highly advanced rail systems that facilitate rapid mail dispersal. Travel to Switzerland from Aachen required transit through Prussia and Baden or Prussia, Hessen and Wurttemburg. While the German-Austrian Postal Union provided a structure for cooperation, the various states were still concerned about how postal revenues were split, so it can be very interesting to investigate the various postal markings on mail that traveled through the German States during this period of time.

In the case of the item above, the markings include the Prussian "Aachen" marking on the front, a Baden railway marking on the back and two Swiss markings also on the back. See the exhibit page in Figure 4 for date and location details.

Figure 5 - 28 cents paid only to the border of Switzerland

The Prussian system is interesting in that it would allow mail from the United States to be mailed 'to the outgoing border.' In other words, the sender could opt to pay the 28 cent rate to get a mail item to anywhere within the German-Austrian Postal Union (GAPU). Once it reached the border, it would be sent on - essentially as an unpaid piece of mail from the Prussian system to its destination in Switzerland. The recipient was required to pay 10 rappen in Swiss postage for the privilege of receiving their mail in this case. All of the 10 rappen were retained by Switzerland as far as I have been able to ascertain.

The 28 cents in postage was divided into 7 cents for Prussia and 21 cents for the United States. The U.S. was responsible for covering their own surface mail costs and paying for transit via England (which included the trans-Atlantic portion). The Prussian mail system paid Belgium for the transit via Ostende (the equivalent of 2 US cents) and it retained 5 US cents for travels through the GAPU mail systems. There are no markings on this cover that illustrates any distribution of the funds between the various German States.

Bremen or Hamburg Mail Treaty to Switzerland

Bremen and Hamburg were two Hanseatic cities that negotiated mail treaties with the United States which included mail service to Switzerland beginning in July of 1857 at a rate of 27 cents per 1/2 ounce. The rate was reduced to 19 cents in October of 1860 and became obsolete when these mail systems were combined with the North German Union postal system in January of 1868. Mail packets (steamships) traveled between New York and Hamburg initially every four weeks increasing to every other week (alternating with the ships that traveled to Bremen).

Figure 6 - Switzerland via Hamburg Mail

Mail from Hamburg and Bremen typically traveled through Frankfort (Hessen territory) and would go through Baden for destinations in Western Switzerland and Wurttemburg for destinations in Eastern Switzerland. Of course, this rule of thumb could be broken if rail schedules were more favorable for other routings.

Figure 7 - US to Switzerland via Hamburg Mails at double the 19 cent rate.

The exhibit page is not accurate with respect to the postage breakdown in this case. First, the blue "8" is likely in silbergroschen, which would translate to 19.2 US cents approximately. It appears that the blue "8" was applied in Frankfort A Main, which would imply entry into the Thurn and Taxis posts. If that is the case, then they would have kept 6 silbergroschen for their transit of mail to Switzerland and 2 silbergroschen would have been passed to Switzerland for their surface mails (about 5 cents). I believe the red marking next to the "8" is "2 fr"* which represented the amount passed to Switzerland.

* I am fairly certain about the "2" and less about "fr."

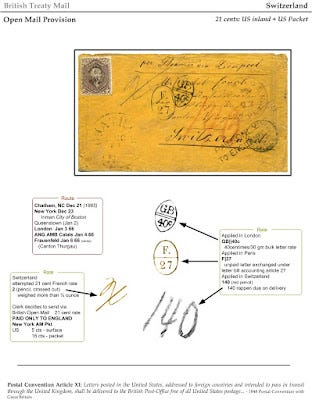

British Open Mail to Switzerland

The postal convention with England had a fully prepaid option to Switzerland from March of 1848 until June of 1857. After that point, there was no prepaid option from the US via British mail. Instead, a person had the option of paying the U.S. portion of the postage and then allowing the British Open Mails to arrange to have the letter sent to its destination, where all costs of mailing from the British system to its destination would be collected. While this open mail was not in effect for all possible destinations, it was available for most European locations.

Figure 8 - Switzerland via British Open Mail

The open mails were especially valuable for mail that was overweight but not paid as such - just as is seen in the item shown on the above exhibit page. The sender appears to have intended to pay the 21 cent French rate to Switzerland. However, the item must have weighed more than 7.5 grams (1/4 ounce), which would require 42 cents in postage. The postmaster realized that at least some of the postage applied to the envelope could be useful by paying the US portion of the trip to England, so the item was sent via the British Open Mail (21 cents per half ounce since an American contract ship took this mail across the Atlantic).

Figure 9 - An alert clerk prevented loss of the entire 24 cents postage paid by using British Open Mail

It was up to the Swiss postal service to collect sufficient postage to cover the costs that were now to be split between the British, French and Swiss postal systems. To simplify the accounting of the time, debits and credits were often (but not always) dealt with in bulk rather than a letter by letter basis. For example, the British and French agreed on 40 centimes for every 30 grams of bulk mail. The justification for this is partially based on an assumption that 30 grams would represent three to four pieces of letter mail on average. Rather than having an exact count of mail pieces and the rates paid, the entire mailbag could be weighed out to figure what was owed for the British (and later French) transit. This is, of course, an efficient way of doing business as long as the actual averages held true to the estimates. But, from a postal historian's perspective it makes it difficult to make the postage breakdown nice and neat. I am sure this postal historian can get over that small issue.

For an initial take on the breakdown, please view the exhibit page in Figure 8.

Why Choose One Option Over Another?

With five different options for sending mail from the US to Switzerland, how was a person to choose?

French Mail: 21 cents per 1/4 ounce

British Open Mail: 5 cents per 1/2 ounce OR 21 cents per 1/2 ounce with remainder to be collected from recipient in Switzerland.

Prussian Closed Mail: 33 cents per 1/2 ounce (35 cts prior to May 1863)

Prussian Closed Mail to border: 28 cents per 1/2 ounce with remainder to be collected from recipient.

Bremen or Hamburg Mail: 19 cents per 1/2 ounce.

Clearly, if cost were the only consideration a person might prefer Hamburg Mail, French Mail or British Open Mail. But, the French Mail rapidly loses its luster if the mail item exceeds 7.5 grams (now it would cost 42 cents).

Hamburg Mail looks good at 19 cents per 1/2 ounce. But, what happens if you missed the most recent sailing of the ship for Hamburg? You would have to wait one more week for the next departure to Bremen (or two to Hamburg). Are you really willing to add another seven days to the typical 12 day transit period? That means you would have to wait nearly a month for a reply. The other mail systems benefited from being able to receive mail from multiple sailings each week.

British Open Mail and Prussian Mail to the border both require that the recipient foot part of the postage. This may not be the best policy if you actually want the recipient to accept what you have sent to them. After all, they were not required to accept and pay for these items. On the other hand, there are multiple instances where it is clear that two businesses intended to split postal expenses in this fashion, so perhaps it was a reasonable option in those circumstances.

The hardest option to consider is the fully paid rate via the Prussian Closed Mails. If the letter item was between 1/4 and 1/2 ounce, this option is clearly better than French Mail (42 cents). If you were also concerned that the recipient accept the mail and not have to pay to receive that mail AND you found yourself in a position where you didn't want to wait a week for the next Bremen or Hamburg sailing, then Prussian Closed Mail is your choice.

As might be expected, my observations have shown more mail addressed to Switzerland from the United States using French mail or Bremen/Hamburg mails than the other options. Since my focus is on items with the 24 cent stamp, it makes sense that I wouldn't pay as much attention to mail heading to Switzerland until a double rate letter came via French mail came along. In fact, the only natural fit is Prussian Mail options or multiples of the other rates. Otherwise, there is the possibility that a person used a "convenience overpay" as is shown in the British Open Mail example above.

I suppose if I were concerned about 'completeness' for this destination during the period, I should find a fully paid Prussian mail item and an item that went via Bremen (as opposed to Hamburg). But, I think I'll be happy with where I am at for the time being.