Like a Fly to a Bug Zapper - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

This week we're going to give myself a bit of a breather. And before you get too worried, that doesn't mean there won't be a Postal History Sunday. What it means is that I am giving myself permission to not dig as deep into things as I often do. Instead, I am going to answer a question that came to me from three different people in three different forums. Of course, they did not ask in exactly the same way, but I kind of liked how Majid Hosseini asked it, so I will quote here:

"Considering your varied topical interests, I wish you did a post some day about what makes you interested in a cover."

Ok! Let's have a little fun with this question and maybe learn something new while we are at it.

The Training Ground

When I started paying attention to postal history, I was pretty overwhelmed by all that was out there. So, I made a choice to find a filter so I could focus on a smaller area. Initially, my filter was postal history that had stamps from the 1861 United States postage series. But, it became apparent that this was too broad and I narrowed it to postal history featuring just the 24-cent stamp of this series.

The majority of the mail using that particular stamp was sent from the United States to the United Kingdom to pay the 24 cent rate for simple letters weighing no more than 1/2 ounce. So, if I was reading books, or looking at catalogues - trying to view examples of this stamp on covers - I would find lots of things that looked kind of like the cover shown below.

These covers typically featured a single 24-cent stamp. There was typically a town postmark and cancellation showing where the letter was mailed from, a red circular marking from an exchange office (like New York) and often a receiving exchange marking for London. That was a typical 24 cent cover to England. And, once I saw enough covers that looked like this, I was able to train my eye to see hints that things were different.

That brings me around to the cover I showed first in this blog - and I'll show it again here.

This folded letter was actually described as another 24 cent cover to England because it has a single 24 cent stamp. But, because my eye had been trained to look for this sort of thing, I noted some differences right away. The first thing that told me the description was wrong was the word "Franco" in blue that is down and to the left of the stamp.

That was enough of a difference that I was encouraged to investigate.

Mailed from New York City in November of 1867, this letter was destined for Venice, which had been incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy after the war with Austria in 1866. The route for this letter went through Bremen, which was part of the North German Confederation in 1867. But the United States was still operating under a mail convention it had negotiated with Bremen.

It just happened that there was a 24 cent postage rate for mail from the United States to Italy for a very short period of time (from February to December of 1867). This postage rate was only effective for mail sent via the city of Bremen and their mail services. As a matter of fact, there are only a few existing covers out there that show this rate, so the fact that I found one masquerading as a cover to the United Kingdom is pretty neat - if you ask me.

But, I found it because I had become very familiar with what was normal. And, it was NOT normal to see the word "Franco" on a cover with a single 24-cent stamp. That was all it took to clue me in on the fact that I might want to pay more attention.

Jumping off to related areas

Once I became comfortable with mail from the US to the UK in the 1860s, it wasn't all that hard to figure out how mail that went the other direction worked. It took much less time to figure out what "normal" would look like for simple letters traveling from places like London and Liverpool to various destinations in the states.

In fact, it would look a lot like the cover shown above, with one exception - there would be only ONE green, 1-shilling stamp on the cover because 24 cents was equal to 1 shilling. The red "paid" marking was pretty normal, and so was the red "5 cents" marking. But, my brain was alerted to the fact that there was a red "5," which would tell me this was a simple letter that should cost ONLY ONE shilling.

Yet, here it was with 2 shillings in payment. It turned out that the explanation was on the back.

The Liverpool marking has the abbreviation "F.R.H." at the bottom, which stands for Floating Row House. Liverpool had a special post office on the wharf for ships leaving to carry mail across the Atlantic Ocean. A person who was too late to get the letter to the regular post office could pay an extra shilling to get their letter on the ship almost to the point of departure by coming to the Floating Row House.

And that explains the extra shilling. But, it was my recognition that the "5 cents" and two 1-shilling stamps wasn't a normal pairing that clued me into researching this item more.

Looking for more explanations

This whole time, my main collection and interest has remained with the 1861 24-cent postal history. But, I am driven to understand those items in my collection as fully as I am able to. So, when I find something else that might help explain more of the story, it attracts my attention.

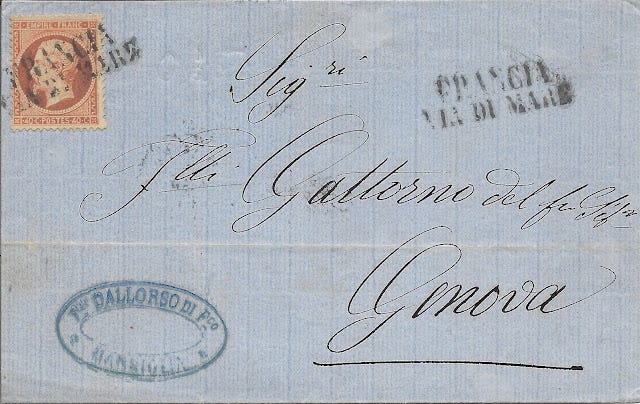

For example, the 1867 business letter sent from Marseilles, France to Genoa, Italy provided me with a foothold to better understand how letters might travel between France and Italy. The key this time is the marking at the top right that reads "Francia via di mare," which would translate to "France, via the sea." This marking was applied to indicate that the letter was placed on a coaster steamer in Marseille and taken off at Genoa.

Then there is this 1862 folded letter mailed from Boston to Rome. It bears 27 cents in postage (including the 24 cent stamp) that properly paid the 27 cent rate for a letter mailed via France to Rome. The marking below shows us that the letter was received on April 5.

If you do not know what you are looking for, the words in the bottom curved panel of this marking read "via di mare." Now that you've seen it with the letter from Marseille to Genoa (or now that I've pointed it out to you), it is easier to try to decipher it here. But, imagine that you had not seen these two covers in this order. Would you be able to decipher what that bottom panel said?

Well, in my case, I was happy enough to be able to decipher the date of arrival. And, for quite some time, that's as far as my understanding went. Then, I realized at some point that mail to Rome probably had to be taken by ship, because Rome was not getting along all that well with the rest of Italy.

THEN I saw that letter from Marseille to Genoa with the words "via di mare" and it all clicked.

This explains some of the items that attract my interest - they represent a way to better understand MORE of the mail processes that the 24-cent covers would have used as they went to, or through, Europe.

But, something else happened along the way as I was looking for more in-depth knowledge.

Something new to explore

I started to realize that I now knew enough about mails in the 1860s that I actually had just enough to not be completely lost if I looked at European mail during that period. In fact, I was able to make at least some inroads for items dated from the 1850s to the 1870s.

Let's be honest with ourselves here. It can be pretty difficult to really enjoy the learning process when you have NO IDEA where you should start, right? Sure, some of our most important and critical learning events in our lives are the most traumatic. But, I'm not doing this because I want to be traumatized. I want to learn and I want to allow myself to enjoy learning.

That means it makes sense to continue to build off of the areas where I already have some foundation to reach from.

Shown above is a letter that was mailed in Torino on July 26, 1863 - and the destination was also in Torino. A five centesimi stamp pays the local postage rate of the time for the Kingdom of Italy. But here's where it starts to get a bit odd. The fancy letterhead, shown below, tells us that the sender, Giuseppe Bonetti, was located in Cremona. If this were mailed in Cremona, it would not qualify as a local letter.

This is where experience in reading dockets for items in the 24-cent 1861 collection comes in handy. It tells me that information could be found if you read such things and we have one that looks like this at the top left of the cover. And it simply says "favore."

This likely explains things more fully. This letter was taken to Torino for Giuseppe Bonetti by someone other than the Italian postal services. Perhaps he had a business acquaintance who was on their way to Turin (Torino) and they were willing to take a letter or two with them and drop them at the local post office, saving Giuseppe a little bit of postage. Maybe Giuseppe even paid a little bit of money for this person to carry a few letters to Turin for him, but it was likely less cost than it would have been to mail it in Cremona.

Things that hint at a story to tell

Of course, as I explore more and more things, I have gotten a bit better at recognizing things that might have a story to tell, such as this May, 1944, registered letter that was returned to the sender because it must have had some content the US mail censor was disinclined to allow to leave the country.

This letter is eighty years younger than most things I pay attention to for postal history, yet I still find it to be interesting. Covers with potentially stories are the thing that make me feel like I am a fly attracted to a bug zapper. I know that I am less familiar with mail during this time period and I am fully aware it will take me longer to work out the details that might be discoverable. But, I can't help it. I smell a story - and I am hopeful to unlock that story (and maybe share it here) someday.

As a matter of fact, one of this year's Postal History Sunday entries I am most proud of features this World War I period envelope. This one was titled Friends in Need and it featured the Friends Ambulance Unit that was established in London to provide medical support in France and Belgium where fighting was heavy.

Overall, this letter is, as far as I can tell, fairly unremarkable for a registered letter sent from the United States to London in 1916. The mail censorship was a fact of life for mail going between these two countries. Registration of mail items was not at all uncommon.

But, that hook to the Friends Ambulance Unit snuck its way into my brain and I just had to take a learning journey.

Personal connections

I am just like anyone else in that my attraction to some things are based mostly on some sort of personal connection I might have. This 1923 letter from Germany to Muscatine, Iowa, is fairly nice looking and it illustrates a postal rate during the hyper-inflation period.

But, the initial attraction to me was more personal than it was postal history. First, Tammy's grandfather was a stamp accumulator and was proud of his German heritage. I still think of him when I look at postal history from this area. Second, we have an Iowa connection - my home state. And finally, the person from whom I purchased this item, for all of one dollar, was a kind soul who was continuing to attend small stamp shows in Iowa as a dealer of postage stamps (and a few covers). He always made me feel welcome - so I think of him when I look at this item.

Fulfilling childhood wishes

I actually "started" collecting stamps very young, when Mom would cut stamps off of the mail and give them to me when I was three years old. I remember gluing them into a little notebook and drawing around (and sometimes on... hey! I was three!) them. But, as I got old enough to learn how to handle stamps "properly" there were certain designs that caught my eye, like the 1913 Dutch issue of the time.

Part of the attraction was that these were a different shape and there were many different values in the set. So, it should be no surprise that I might like to acquire an item that represents a stamp issue I recall being fond of back then.

The envelope above has a pre-printed design with vegetables, so you can guess why a vegetable farmer, such as myself, might find a personal connection here as well. But, when you add to it the fact that it shows a nice, clean example of the cheaper printed matter rate (Drukwerk), that makes it interesting for me.

Things that have curb appeal

When a piece of paper, like an old envelope or folded letter that went through the mail, still looks pretty new even though it might be fifty, eighty, or one hundred and fifty years old, it is bound to get my attention. If the postal markings are clear and boldly struck and the hand writing is neat, I can't help but notice. If the postage stamps have nice color and the edges of the envelope or paper are not tattered, why wouldn't I want to look at it a second or third time?

There are aesthetics when it comes to postal history. And that might come as a bit of a surprise to those of you who do not do anything more with the hobby than read a Postal History Sunday now and again. But, the odd thing about those aesthetics is that things do have to look their age - as long as they don't look TOO MUCH their age.

Although, sometimes, the ugly duckling finds a place in your heart. Even if you wince a bit when you look at it. I guess we need to remember that we all need love. Maybe a tattered envelope that was mailed in 1865 from Indiana to Australia qualifies for some of that love?

A nutshell to simplify it all

Now that we have done all of that, I'll summarize my answer to Majid and others who were asking.

What makes me interested in a cover or piece of postal history?

Primarily three things:

An item that helps me learn something new about postal history

Something that gets me interested in a story

Things that might help me recall the memory of a person, place or event

And now you're all saying, "Why didn't you say that in the first place? Instead you just rambled on and I neglected to refill my mug with my favorite beverage."

Well, here's hoping you were in a comfortable chair and your fluffy, bunny slippers kept your feet toasty warm. All is not lost, because your worries you put down to read Postal History Sunday were run through the wash machine with your extra socks. If you're lucky, you aren't missing a sock this time. Instead, it was your troubles that went missing.

And that makes for a good day. Thank you for joining me. Have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come.