More Favorites - Postal History Sunday

Hello everyone! It's good to see you (virtually) visiting this week's Postal History Sunday. Everyone is welcome here, whether you are an avid postal historian or are just idly curious about why that crazy farmer likes these old pieces of paper! Tie your troubles to a firework and let them shoot up into the sky where they'll explode into tiny, glittering shooting stars. Put on the fuzzy slippers, get a favorite beverage and enjoy a few minutes while I share something I enjoy.

This past week has been an exceptionally difficult one, so we're just going to keep this one relaxed. The theme this time around is motivated by a couple of questions I received. One person asked me if I had a favorite Swiss cover in my collection and another asked if I had a favorite cover from the 1900s. So, we're just going to look at a few of my current favorites and see where it goes!

About that favorite Swiss cover....

I have not yet featured this particular item, though it may have been used to illustrate some point somewhere in the middle of a Postal History Sunday in the past. This is a simple letter that was mailed in Basel, Switzerland, with London as the eventual destination. A green 40 rappen postage stamp and an orange 20 rappen postage stamp combined to pay the 60 rappen required per 7.5 grams of weight if the letter was sent via France (which this one was). This postal rate for mail from Switzerland to the United Kingdom via France was effective from August 15, 1859 to September 30, 1965.

The postal markings help tell us how this letter got from here to there:

Basel Briefexpedition Sep 24, 1859

Suisse -3- St Louis Sep 26 (marking applied in Paris)

Paris A Calais Sep 26 (on the back of the letter - applied on a mail train)

London Sep 27

The default route during this period was for mail between the United Kingdom and Switzerland to be taken through France as the intermediary postal service. However, there was alternative! Mail could be sent via the Prussian and Belgian mail. But, if a letter was very light (less than 7.5 grams), this was a cheaper alternative. A slightly heavier letter weighing over 7.5 grams and no more than 15 grams would actually be cheaper if sent via the Prussian service. Perhaps, one day, I'll be able to illustrate an example using each option - but today is not that day.

My reasons for liking this cover have to do with the clear markings and the overall clean appearance, of course. But, it is a bit more than that. It has more to do with how often a person gets to see something. In general, foreign mail from one country to another becomes less common the further from each other they get. It is not so difficult to find letters from Switzerland to France or Italy or various German States. But, once you select a destination that is not bordering Switzerland, it becomes a bit harder to find examples.

It isn't so much about rarity, however, for me. In my case, it provides me with an opportunity to study how mail travels from one postal service, then through an intermediary (France) on its way to the destination postal service.

Another Swiss cover that I considered selecting has been featured in its own Postal History Sunday here and two others were part of this entry.

A favorite cover from the 1900s

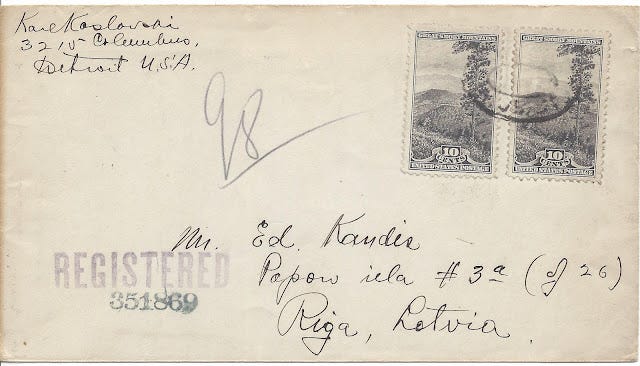

Shown above is a letter mailed from Detroit, Michigan to Riga Latvia in September of 1935. This was sent as a registered letter via surface mail to a foreign country and two 10-cent stamps were used to pay for the postage and the registered mail fee.

What is surface mail? Its counterpart would be air mail, which was beginning to get a foothold in the 1930s. Surface mail was less expensive and could use various modes of transportation via ground and water to get to where it was going.

In the case of the letter above, it likely took a train to a port city, such as New York or Boston, and boarded a ship to Europe. By the time we get to 1935 there were many options for mail to be carried over the Atlantic and the lack of markings do nothing to help us figure out the route this might have taken.

In 1934, a series of ten stamps were issued to honor the National Parks of the United States. Each of the ten stamps had a different denomination, from 1 cent (Yosemite) to 10 cents (Great Smokey Mountains). The stamps on this cover were the denomination that was issued last (put on sale October 8, 1934). If you have interest in reading more about the background of these stamps, there is an article with large pictures of each denomination offered by the White House Historical Association.

This series of stamps was one that caught my attention early in my collecting endeavors. As a kid, with a kid's budget, I was pretty much able to acquire things with minimum value, often given to me by relatives. The National Parks issue of 1934 had a few values that fell under that category, but the 10 cent Great Smokey Mountains stamp was not one of those. If I recall correctly, it had a catalog value in the neighborhood of $1.70, which was a relative fortune. In fact, a nice copy of this stamp was probably my first targeted purchase for my collection.

I think we all have things that trigger early memories and many of us are fortunate to have pleasant memories we don't mind recalling. This stamp issue does that for me. And, the ten-cent value has a personal significance. So, when I came across this particular item from Detroit to Riga, I did not have to think too hard about adding it to my personal collection a couple of years ago and it remains a favorite.

How about a favorite 24 cent cover?

Ok, I did not JUST hear this question, but it is a fairly common question I get since this is the main focus of my interests. It's also, kind of an unfair question because I like all of them (of course). But, it is not unreasonable to expect that I may appreciate one more than others at any given time.

There are many that I think I would not be faulted for selecting, but this is one that has been with me for some time and the complexity and the story that surrounds a very good looking piece of postal history is hard to beat.

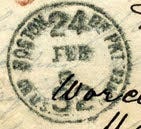

This letter was mailed in Worcester on January 2 of 1866 and arrived in London on January 13. Baring Brothers & Co had managed the Honorable P.C. Bacon's line of credit and provided the mail forwarding service. They apparently figured out that he had left (and not left them with a balance to cover forwarding costs for mail that needed to get sent on the U.S.). As a result, they remailed this letter in London on January 20 and sent it back to Worcester as an unpaid letter.

This letter retraced its steps - taking the train from London to Holyhead, crossing the St Georges to Kingston and then taking the train to Queenstown. Once there, it left on the Cunard Line's Africa on January 21 which arrived at February 3 in Boston.

Baring Brothers applied no stamp and they apparently did not pay ANY postage for the return trip to the United States. That means the recipient would be required to pay the postage for that return trip.

This is the key marking on that cover that tells me what the Honorable P.C. Bacon was going to have to pay the United States post office in order to read the letter that traveled across the Atlantic Ocean twice. The marking is in black ink - just one indication that the item was received unpaid. P.C. Bacon could either pay 24 cents in proper coin or he could pay in "greenbacks" (also known as depreciated currency) to the tune of 32 cents.

This story is a good one and a favorite of mine. If you would like to read about it in more detail, you can go here.

An item I am looking forward to learning more about

Shown above is a letter mailed from Christiania (now Oslo), Norway to Paris, France in 1869. There are fifteen skillings worth of postage on this letter, which seems to be correct based on observations of other letters from Norway to France during this time period. I can probably construct a likely route as well based on what I know now.

But, that's the point I am trying to make. I have very little knowledge of the postage rates and routes for Norway in the 1860s. In fact, I am not entirely sure which resources to go to as I start digging. Postal history is a tremendously large and complex area of interest. A person can quickly and easily move out of their area of knowledge and comfort - which is exactly part of the appeal. There is so much one can explore and learn!

Of course, entering new territory can be frustrating, but each time I explore new areas I develop skills that help me to get better at what I do.

One more before we go?

Since I am writing this week's Postal History Sunday on Saturday night after I spent part of the day weeding onions and pushing a wheel hoe, I thought it would be appropriate to share an illustrated advertising cover that features some of the hand tools of my trade.

Shown above are five individuals pushing straddle wheel hoes to cultivate a field of, presumably, vegetables. Either a blade or some sort of tine implement would be behind each wheel (and on either side of the crop). The idea is to cultivate as close to the row as possible without damaging the crop.

The wheel how I use has a single wheel and a stirrup hoe provides me with the blade that follows behind it. So, when I wheel hoe a crop I walk on either side of the row to get as close as I can to the vegetable crop. I have also used a wheel hoe similar to this, but I learned using the single wheel and have become quite proficient at it. I actually find the straddle wheel hoe to be uncomfortable because you have to walk with your feet a bit further apart to avoid stepping on the crop.

The front of the cover illustrates a hand seeder tool with a similar handle system. This type of tool allows you to use your larger muscles and to keep a more balanced and even stature. Anyone who has done this sort of work can tell you that tools that favor one side or the other (like a normal hoe) require you to learn to work both left and right handed unless you want to develop a repetitive stress injury.

Well! How do you like that, I even got a little farming into Postal History Sunday this time around. Always full of surprises aren't we?

Thank you for joining me today. I hope you have a fine remainder of your weekend and wonderful week to come.

----------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.