New Language - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to the space on the blog that occurs every seven days on a Sunday - also known as Postal History Sunday on the Genuine Faux Farm blog. Pour yourself a beverage of your choice and make yourself comfortable. For a few moments, forget about the dirty dishes and put your worries under the place mat on the kitchen table. We're going to take a tour together!

A tour around some selected letters from days gone by!

This week, we're going to teach you a little bit about the language that I read when I look at a piece of postal history. Don't worry, there isn't a quiz at the end! We'll just keep it light and... hopefully... fun!

1863 from Boston to London

I'm going to start us by reading about the trip this letter took from Boston to London, England. There is a single stamp at the top right that represents 24 cents of postage. It just so happens that the price of mailing something from the US to England at that time was 24 cents, so it was cancelled with a round grid marking with the word PAID on it in black ink. This was done so people could not reuse the stamp.

From a historical standpoint, you can guess that the American Civil War was raging, with fighting at Stones River (Tennessee) and Fort Hindman (Arkansas). The Emancipation Proclamation had just gone into effect on January 1. As momentous as all that might have been, business went on.

Perhaps you remember that we talked about dockets a couple of weeks ago? If you don't, you can always take the link and read it at your leisure. For now, we'll just point you to the handwriting at the top center. This was written by the addressee (Charles H Hudson). He recorded for future reference the date he received the letter (January 19), the date he sent a reply (January 24) and who sent him this letter (Rideout & Merritt).

This docket has nothing to do with the postal aspect of this envelope - but it gives us some background as to the purpose of this mail. It also provides us with checks for consistency to be sure all is as it should be here. The red London marking at the right (by the name Hudson) also gives a date of January 19 - that's a match with the docket, so things are lining up nicely!

You might also note that both the London and Boston markings are in red ink and they both include the word "PAID." If you'll recall, we talked about ways the postal service communicated that postage was properly paid in a blog in October of last year. So, this all makes sense - there is a stamp that is the right amount for the postage of the time. There are two markings that seem to show that the postal service saw this letter as paid to the destination. And... the dates line up with expected travel times and dockets.

Let's look more closely at the Boston marking! There is actually more information that I can extract just by knowing what I am seeing - by knowing how to read this "language."

"Br. Pkt"

This is an abbreviation for "British Packet." A packet was a steamship that carried the mail across the Atlantic Ocean. Some mail packet companies had contracts to carry the mail for the United States (an "American Packet") and some had contracts to carry mail for the United Kingdom (a "British Packet"). This marking actually gives me a chance to identify the ship that carried this letter from Boston and across the Atlantic!

On January 7, 1863 the Europa left Boston. This ship was owned by the British & North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company - a shipping line that is often referred to as the Cunard Line (for its founder Samuel Cunard). It arrived at Queenstown, Ireland on January 17 and probably went on to Liverpool the next day.

"19 Paid"

Well, we all understand the "Paid" part. But, what's with the "19?" Didn't we say that it cost 24 cents to mail this letter?

Indeed we did! And, indeed it DID cost 24 cents. The issue is that the United States provided some of the mail service and the British provided some of the mail service. At this time, it was important to account for how much of the 24 cents went to each post office so it covered the expenses.

Five cents covered the mail service within the United States. Sixteen cents paid for the Atlantic voyage. Three cents covered mail service in the United Kingdom. Since the British had the contract with the Cunard Line, they had to pay the shipping company. So, the British needed 16 cents for that and 3 more cents for their own mail services.

This marking simply says the United States must pay 19 of the 24 cents they collected in postage to the British Post Office. They kept the remaining five cents.

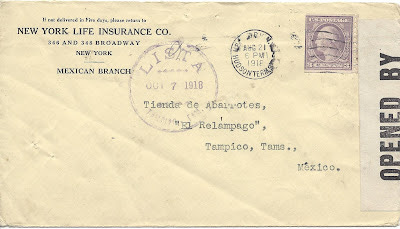

New York to Tampico - 1918

Below is a much more recent letter. The New York Life Insurance Company sent this item from their offices in New York for their "Mexican Branch" to a grocery store company (tienda de abarrotes) named "El Relampago" in Tampico, Mexico. The letter was sent from New York on August 21, 1918. The cost to mail this item from New York to Mexico was 3 cents.

World War I still had a couple more months to go until Armistice Day (Nov 11) when Germany surrendered. The second wave of the Spanish Flu pandemic was just getting underway - fueled by troop movements (among other things). The tape that reads "Opened By" at the right of this envelope shows that this letter was opened by a censor prior to its delivery in Tampico. Interesting enough, censors may well have redacted items that might have been related to military actions as well as the pandemic, feeling that dissemination of information on the illness would give rise to panic.

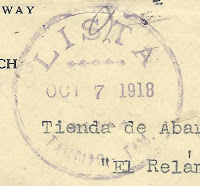

This cover also has another marking that was applied in Tampico. The marking reads "Lista Oct 7 , 1918." Clearly, the letter had been in the Tampico post office for a while, but no one had come to claim this mail. "Lista" is a reference that the item had been advertised in local papers as being available at the post office. This was still a common practice for mail sent as a "general delivery" item. General delivery, also known as "poste restante" in Europe meant that the letter was sent to the post office and not delivered to the recipient by a carrier. It was the recipient's responsibility to come to the post office and check to see if they had any mail.

Le Havre to Philadelphia - 1873

If you detect a big change in postal processes, you can usually attribute it to one or more historical events that led to the adjustments being observed in the postal history. For example, mail handling between the United States and France had been fairly consistent since 1857, when a postal treaty was put into place. Once we get to 1870, letters look quite a bit different. Interestingly enough, France lost to Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which included the Siege of Paris into early 1871. It would be incorrect to say that the war was the sole cause for the change. But, it might be accurate to say that the conditions that led to that war also contributed to the postal changes.

First, we can exercise our "docket reading" once again. The top left reads "Via Queenstown, p. Steamer City of Brooklyn." It just so happens the City of Brooklyn was scheduled to be in port at Queenstown on June 6. This ship was owned by the Liverpool, New York & Philadelphia Steam Ship Company, founded by William Inman. I suspect you see a pattern here. People have historically looked for shortcuts when referencing things - so this company was routinely known as... the Inman Line. (imagine that!) The ship would arrive in New York on June 16.

The words around the circle of this marking read: "Le Havre Le Port." Le Havre would be the city and Le Port would be the post office branch that received this item for mailing. And if you look at the words inside the circle, you will likely recognize the date: June 3, 1873. You might, however, be uncertain as to what the "4E" might reference. Larger post offices had multiple mail distribution and departure time each day. This would be the 4th collection period of the day on June 3. This was apparently early enough for this item to get to London on June 4 by a channel steamship.

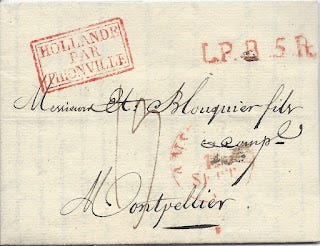

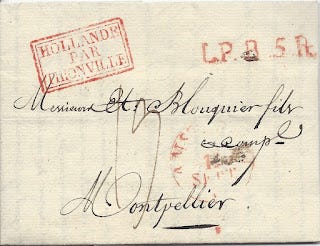

Holland to France - 1836

Now we'll take you back before there were postage stamps! Here is a letter from Amsterdam to Montpellier, France in September of 1836. At this point, the Netherlands was still trying to hold on to Belgium, despite the latter's proclamation that it was independent in 1830. This conflict would not be settled until 1839.

At this point in time, the cost of postage for a letter was calculated as much by distance as it was by weight (or sometimes the number of sheets in a letter). Most letters were sent unpaid or partially paid, with the expectation that the recipient would pay for the honor of receiving the item.

One of the funny things about postal history of the 1800s is that numbers don't always look like the numbers you and I might expect. One must remember that postal clerks were often handling A LOT of mail and we have to expect some shorthand. What was important is that they and their compatriots understood the markings.

What you see above is a "19." This represents 19 decimes or 1 franc, 90 centimes, which was the amount the recipient was going to pay in order to receive the letter. That is a fair amount of money considering the cost would only be 60 centimes when we get to the 1860s.

The postal rate calculation is aided, in part, by this marking that appears at the top right of the folded letter.

L.P.B.5.R. = Les Pays Bas 5th Rayon

The French know the Netherlands as "Pays-Bas" or "Les Pays-Bas," which is literally translated as "Low Country (ies)." This shouldn't sound odd since the English refer to it as "the Netherlands" with "nether" being defined as "lower in position." You could also, of course, refer to it as Holland(e).

The 5th rayon refers to a region or a distance within Les Pays Bas. The 5th region was furthest from France and required the most postage to cover the distance from Amsterdam to Thionville in France. Then, French postage would be added for the distance from Thionville to Montpellier. If you want to know how that works, I went through that process with this Postal History Sunday post!

-------------------------------------------

Thank you so much for taking this little postal history journey with me. I hope you were able to relax, learn something new, and take comfort in the enjoyment I have with sharing my hobby with you. As always, I am happy to take questions and turn them into future "Postal History Sundays." I expect to keep writing them as long as I have motivation and energy to do so.

Have a great remainder of the weekend and I hope your coming week is a good one!