Night Flight - Postal History Sunday

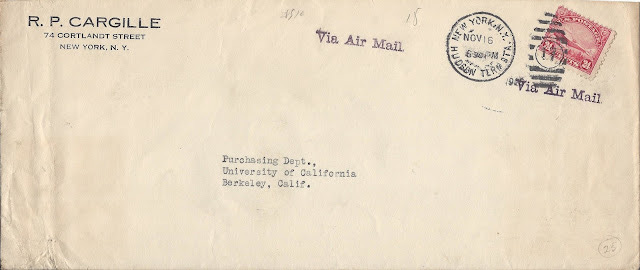

Welcome to Postal History Sunday! This week we're going to take a foray into an area of postal history where I have much less familiarity. The motivation for this is twofold. First, I felt as if the large envelope shown above and mailed in 1924 likely had a good story surrounding it and I was interested in beginning my exploration. That is usually enough reason for a Sunday topic.

Second, I find it useful to move myself out of my knowledge "comfort zone." It's a good reminder to me that many things I see when I look at an item in my area of "expertise" is not always apparent to everyone else. It helps me to improve my ability help others see what I am seeing if I put myself in the position of not immediately recognizing what is going on myself.

So, let's see how I do this time around!

US Air Mail services in 1924

Biplane equipped with lights for night flying ca 1924 - from USPS site viewed 4/15/23

Air Mail service in the United States was still very much in its experimental phase, but by 1921 it was clear that the service was dangerous (to the pilots) and the time savings for the mail was certainly not enough to encourage customers to pay the extra postage it took to use air mail. The exception to this rule (cost-benefit) was the trans-continental route (completed Sept 1920) that ran from New York City to San Francisco. A time savings of 22 hours could be achieved with mail traveling on planes during the day and trains at night.

It is important to remember that pilots of the time did not have much by way of instrumentation to help with navigation and had to rely on what they could see on the ground. To give you an example, the first scheduled flight to carry mail for the US Post Office from Washington DC to New York City in May of 1918 was less than a roaring success.

The pilot, 2nd Lieut. George Boyle, shook hands with President Woodrow Wilson for a flight that was to make its first stop in Philadelphia. Taking off with a map on his lap, Boyle ended up heading the wrong direction. Once he realized the mistake, he landed in a field and damaged the propeller. The mail was driven back to Washington and taken by train to Philadelphia.

Now, just imagine exactly how difficult it was going to be to fly mail planes at night. Unlike the present day, where even large towns have airports with flood lights and every town has streetlights, most of the continent was quite dark when the sun went down. Add to this the uncertainty of the weather that a pilot might encounter as they traveled from East to West and vice versa. The National Weather Bureau existed and did what it could to provide forecasts, but there was a great deal of ground to cover.

Beacon light, 1924 - USPS site

Postmaster General Harry S New indicated that the US Post Office was aware that night flying was going to be necessary in his 1923 Report of the Postmaster General, signalling a new trans-Continental schedule that included night flying to begin on July 1, 1924. Beacon lights were installed along the route from Chicago to Cheyenne, Wyoming every three miles to guide the pilots in the section of the route scheduled to be flown at night. Pilots and planes were changed six times (Cleveland, Chicago, Omaha, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City and Reno) and the mail would leave in the morning in New York City, scheduled to arrive in San Francisco late the next day.

Other advances of note included the development of altimeters to help determine if the aircraft was climbing or descending. Could you imagine trying to figure that out if there were heavy clouds or if it was a moonless night? A gyroscopic needle was also tested to help determine if the wings were level.

This is, of course, a very brief and selective history that I have given here. If you want more, let me suggest you start with the summary history provided by the US Postal Service. There are many more pictures in this companion web document. If the topic area interests you, the American Air Mail Society just might be a good place to learn more.

Using the trans-continental service

Shown above is a envelope that was sent from Fairhaven, Massachusetts, on August 15, 1924 (6:30 pm) to San Francisco, California. The back of the letter has a receiving postmark for San Francisco dated August 17 at 7 PM. This letter likely traveled by train from Fairhaven to New York City so it could be placed on board the plane departing the next morning. It then traveled via the trans-Continental route to San Francisco. In other words, this is a solid example of the air mail service working as advertised.

The route itself was broken into three zones. The western zone (San Francisco to Cheyenne), the central zone (Cheyenne to Chicago) and eastern zone (Chicago to New York City). The postage rate required to use this air mail service was 8 cents per ounce for each zone along the route (effective July 1, 1924 to Jan 31, 1927). This letter traveled through all three zones and must not have weighed more than one ounce, so the postal cost was 24 cents (8 cents x 3 postal zones).

For comparison, it cost only 2 cents per ounce to send a similar letter via surface mail (mail that traveled on the surface of the earth - land or water) from anywhere in the US to anywhere in the US. The difference, of course, was in how quickly the mail arrived. The air mail route from New York to San Francisco averaged about 34 hours in travel time. Surface mail might take 4 1/2 days - or three days slower - during that same time period.

I suspect the letter shown above might be more of a souvenir item, given the nice (but upside down) design on the envelope. Philatelists of the time were often keen to create and secure examples of items that were carried under special circumstances, including this new trans-Continental route being flown at night.

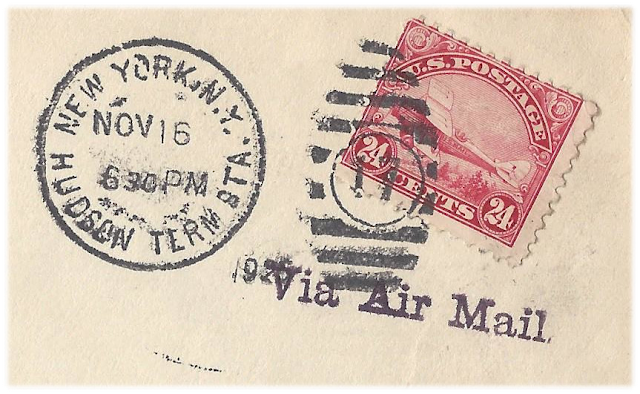

Another example from 1925 is shown above. This envelope is a larger envelope and is an example of a commercial use of the air mail service. The letter was mailed at the Hudson Terminal Station in New York City and received a postmark at 6:30 PM on November 16. It was clearly marked that it was intended to be taken "via Air Mail" and it also bore a 24 cent stamp that was designed for the air mail postage rate across three zones. There were also stamps for two zones (16 cents) and one zone (8 cents).

Since the letter was sent the evening of November 16, it was able to board the departing plane on the morning of the 17th. This time, the letter got an arrival postmark for November 18 at 11:30 PM. If you will recall, the prior example arrived at 7 PM. So, clearly, things did not go quite as well this time around. Not enough to make much difference to the recipient, who would likely receive delivery the next day in either case.

Now that we have two typical examples of air mail letters that traveled through all three zones and used the night mail service to cross the continent, we can return to our initial item that got my attention in the first place!

This larger envelope was mailed in Cleveland, Ohio on November 17, 1924 at 2:30 PM. Cleveland was the first location on the west-bound trip where the plane and the pilot were changed. So, it is my assumption that this letter was ready to join mail that had been placed on the plane in New York City on the new plane that was bound for Chicago (and another transfer to a new plane).

from this USPS site

Cleveland was still in the eastern zone of the trans-Continental route, which means it would still travel in three zones to get to San Francisco. The cost would, once again, be 24 cents per ounce of letter weight. But, this time, instead of one 24 cent stamp, we have three 16 cent stamps to pay the postage for a total of 48 cents. This letter must have weighed more than one ounce and no more than two ounces.

This packet was addressed to the editor of a newspaper in San Diego and the very light receiving postmark appears to be for November 19 in San Diego. This seems to confirm that the letter came into San Francisco on the November 18th flight. It then took the surface mail route to San Diego the next day.

This is, in my opinion, an excellent example of who might avail themselves of the air mail service despite the significantly higher costs. Perhaps a telegraph message would be faster still, but at a cost of 60 cents for a very short message (maybe fifteen words), this was a bargain. Consider that it takes almost five sheets of modern 8 1/2 x 11 printer paper to get to one ounce and you can see that a fair amount of material could have come in this envelope.

The sender of this item, the NEA (Newspaper Enterprise Association) Service in Cleveland, was a syndicate that distributed news articles, cartoons and sports features to newspapers. At about the time this item was mailed, NEA Service was distributing material to over 400 different newspapers. It is likely that the contents of this envelope were important and timely news stories of that time. Perhaps someday, I could dig into the archives of the NEA proof books and figure out what might have been important enough to send on the night plane to San Francisco.

Thank you for joining me for Postal History Sunday. I hope you found it enjoyable and that you have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

--------------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.