Planting A Seed - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

This week, you're all going to get a peek at another side of my life. A place where pieces of postal history connect with our small-scale, diversified farm (the Genuine Faux Farm). This time around, Postal History Sunday will focus more on the illustrations on the covers, than we will the postal markings.

It was not that long ago, in the grand scheme of things, that multiple seed houses could be found in every state in the US. Most seed houses had their own breeding programs and might tout some of their best varieties in their advertising.

Wide Range of Breeding Programs

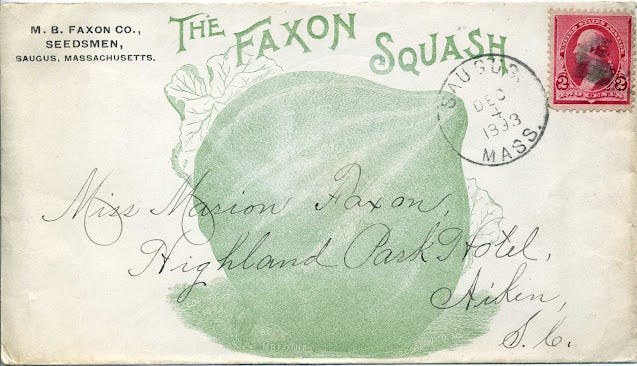

The Faxon Squash is listed in the Biodiversity Heritage Library as being introduced in 1894. And here we have an advertising cover mailed in December of 1893 featuring that squash. This item was mailed from Saugus, Massachusetts - the home of M.B. Faxon Company to a Miss Marion Faxon, who must have traveled to Aiken, South Carolina for an unknown (to us) reason. While this was probably a use of an advertising cover between members of family, we can still be grateful that they were willing to use (and then keep) these envelopes so we can see what they look like today.

Shown above is a page from their 1894 catalogue that is made available by the Biodiversity Heritage Library. The catalogue itself certainly features some of the varieties they specialized in, but they also offered seeds from other companies, such as Burpee. This was a pretty common practice. A seed company would focus on producing particular seed varieties (which this company referred to as "Faxon's specialties) and they might also work on breeding programs. To provide a broader seed offering to their customers, seed companies like this one would often would rely on other seed producers.

If you read the text for the catalogue introduction of the Faxon Squash (shown below), this was apparently their first success at developing their own squash variety that they felt was worth marketing.

The M.B. Faxon Company had a fairly widespread distribution of their catalogs in the late 1800s - so we should not make the assumption that a this seed house only sold locally. However, the sheer number of seed houses throughout the world meant there were many more locations and organizations seeking to select for varieties that did well under regional growing conditions. From our own experience, we can provide you with anecdotes where a variety that went by the same name from one seed house did poorly at our farm while that same variety from another seed house did well. In fact, we often find that seed produced in our own region (if we can find it) is better adapted to our farm.

Perhaps a short side-bar would be of interest right now? If a seed producer desires to grow seed of a known variety, they will plant a crop with that seed and go through a process called selection as that crop progresses. Any plant that does not look "true to type" is removed, as are weaker plants. The idea is to select seed from those plants that are the strongest and exhibit the best qualities of the vegetable variety being grown. Faxon was selecting seed for their "specialty varieties."

The Faxon Squash was a different matter. This seed company was developing a hybrid by carefully cross-pollinating existing squash varieties. This process can be a major undertaking because the pollination process is often done by hand - and multiple trials usually have to occur at the same time to see which results in the kind of fruit/plant that is desired. Then, you have to hope that the seeds from these crosses would come back true to type, thus creating a new variety of squash.

The very nature of growing to produce seed implies careful attention to how the plants grow and how hybrid crosses pan out as they are developed. Can you imagine how many different breeding and selection projects were running concurrently in the United States with multiple seed houses in most states?

As far as I have been able to tell, the M.B. Faxon company seems to have stopped publishing catalogues in the early 1900s and I am not sure if any strains of the "Faxon Squash" might survive today. On the other hand, I CAN show you that we do grow several varieties on our farm that have a long history. They are often referred to as heirloom and heritage seed. Shown above is the Thelma Sanders Sweet Potato squash, which is a type of acorn squash.

A.H.Ansley and Sons Hits the 'Big-time'

Shown above is another illustrated envelope with two cents of postage paying the internal letter mail rate in 1893. This item was sent to the Perkins Wind Mill Company in Mishawaka, Indiana, by the seed company in Milo Centre, New York. A pencil notation on the side reads, "I want a mill with graphite bearings." This would seem to indicate that this was not an offer to sell seed, but rather a request to purchase equipment.

As mentioned earlier, there were many more seed houses and they came in all sorts of sizes with many kinds of specialty crops. Some of the smaller, more local seed producers, such as A.H. Ansley and Sons might concentrate on developing and growing out particular crops for seed. Every so often, these companies might hit on a winner.

The smaller, local producers wouldn't necessarily have the publicity to push a particular strain, but there were certainly larger concerns, such as W. Atlee Burpee & Co that might be willing to purchase the rights to introduce it to the public at large. Some things may be no different then that they are now, as I suspect Burpee introduced the "Perfection Wax" without giving any direct praise to Ansley.

There is evidence, however, that Ansley & Son was still in business in 1900 and they were still focusing on wax and pole beans. The following was in the US Department of Agriculture - Division of Entomology, Bulletin No. 33 prepared F. H. Chittendon and published in 1902.

June 18, 1900, we again received specimens of beetles... with report that

they were injurious to several acres of white pole beans at Milo Center,

N. Y. Our correspondent, Mr. A. H. Ansley, stated that nearly one-

fourth of the plants above ground at the time of writing were riddled

by the insects. Attack was first noticed June 16. when only an occa-

sional plant was being eaten, but at the date of writing many more

of the beetles were seen, and the first plants infested were dried and

crisp except a young center leaf just budding out. Sweet corn and

other plants in the vicinity appeared to be exempt from attack.The report above was in reference to the Smartweed Flea Beetle. It's just a reminder that pests, weeds and diseases are not a new thing and it is also a reminder that nature tends to have its way with monocrop (single crop type) systems.

The Myth of Perfect Veggies Has Long Tradition

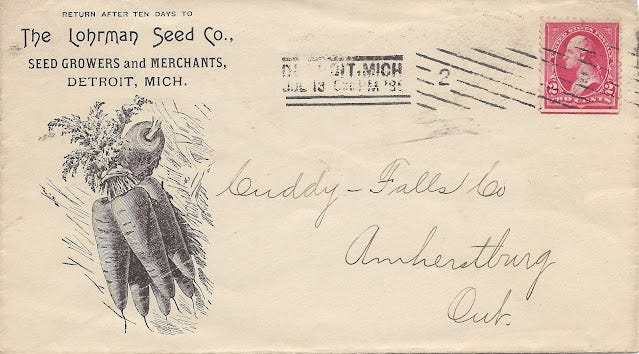

Here is an 1898 envelope featuring carrots offered by the Lohrman Seed Company in Detroit, Michigan. You might want to note that Lohrman touts themselves as "Seed Growers and Merchants," making it clear that they both grow out seed and sell that seed to the public. Not all seed producers created catalogs with the intent of selling to the public. Some might, perhaps, simply grow out plants to produce seed under contract for other companies who would then sell the seed.

It is true that a grower of produce wishes that a significant portion of the crop looks like the perfect picture that is always shown in the catalog (or in this case, the perfect carrots on the envelope). But, perfect looks have never guaranteed satisfactory taste. Nonetheless, it is clear that consumers have always had a problem accepting that a tasty carrot just might not have that perfect wedge shape.

Lohrman's 1922 catalogue features a carrot type (Chantenay) that might well have been the model for the advertising design on our envelope. The introduction to that catalog touts their forty years of experience, which clearly confirms their existence at the time this letter was mailed.

The letter was mailed to Cuddy-Falls Company in Amherstburg, Ontario (Canada). According to the 1899 Essex County Business Directory, Cuddy-Falls were bankers. Maybe the bankers wanted to grow some carrots? Perhaps they wanted to invest in their own health and well-being.

-----------------

We came in Saturday evening after completing our farm chores and reflected on the squash harvest (butternut in this case) we had just pulled in earlier in the day. My mind was on the farm and on growing produce, so it should not be a surprise that I should fall back on this topic when faced with the reality that Sunday was only a few hours away.

I hope you enjoyed today's installment of Postal History Sunday. Have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come!