Poo d'Etat - Postal History Sunday

You have been traversing the virtual world of the internet and now you find yourself here, reading this week's Postal History Sunday that is hosted on the Genuine Faux Farm blog or the GFF Postal History blog. Don't worry about wiping off your shoes for this one, but do take a moment to get yourself comfortable and grab a favorite beverage or snack. This week's entry is going to take us to some different territory - maybe we'll all learn something new by the time it is all over with.

One thing I cannot escape is the reality that I am a farmer AND a postal historian. Rather than run and hide from this, I do my best to embrace it. So, today's PHS blog is going to take a turn towards the farm - and more specifically, towards fertilizer! That encouraged me to name this one "Poo d'Etat." Hang on and enjoy the ride!

------------------

When I first noticed this envelope, I have to admit that I was not horribly impressed. It's not the prettiest item out there and there is some staining and aging that made me pause. There is not much for postal markings either - and the cancellation doesn't really give me a too much information.

The addressee may have been a law professional (note the letters "Esq" after the name) who could be located at Nottoway Court House (about 65 miles southwest of Richmond, Virginia). As the name implies, this settlement was the "business portion" of the county, which included the court house building, clerk's office and jail. The Fitzgerald family were quite prominent in the early history of the county, with numerous members serving in the legal profession and others claiming to be doctors.

If you would like to learn more, you can go to Old Homes and Families of Nottoway County by W.R. Turner in 1932.

The postage stamp is a 2 cent issue from the 1869 US issue and it pays the rate for items that were classified as a "circular." The rate for this class of mail was effective from 1863 to 1872 and allowed the sender to put up to three copies of the circular into one cover (envelope or wrapper of some sort). To qualify, the contents could only be printed matter (with no written personal messages placed in addition to the printed matter). The envelope also needed to be left unsealed so the postal clerks could inspect the item to be sure it met regulations.

What attracted me to this item in particular was not the envelope itself. It was not the addressee or even a possible connection to historical events. It was not the stamp, or the rate of postage it paid.

It was the contents.

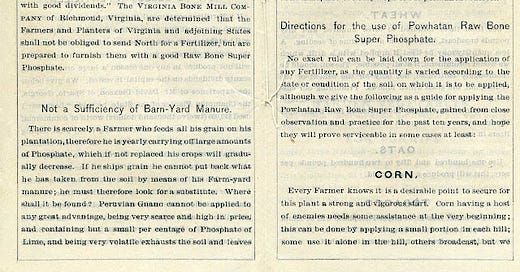

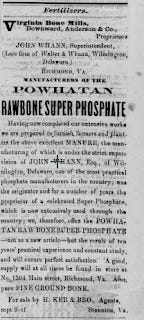

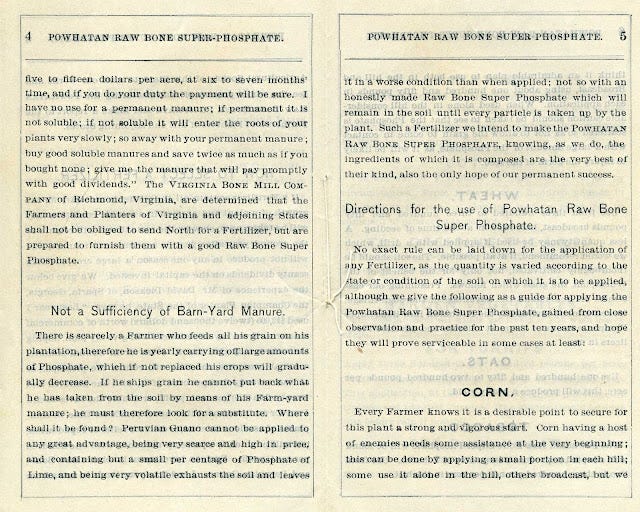

The envelope held a booklet that was still in excellent condition. And the booklet extolled the value of the Powhaten Raw Bone Super-Phosphate to be used as fertilizer on a wide range of crops.

Before I get into that side of things, it makes sense for me to talk about WHY contents are often a valuable part of a postal history artifact. Sometimes, the envelope or wrapper, by itself, leaves us with more questions than answers. In fact, as we could see from last week's PHS post, there are times when we have to determine whether or not an item has been tampered with, or if it has suffered losses over time. But, even if it is not a matter of authenticity, it IS a matter of determining an accurate story that includes when an item was mailed, how it went from place to place, the postage required to carry it, and if there were any special circumstances that made the travels of this piece of mail exceptional!

If you look at the envelope again - we don't know where it was mailed from. We don't know when it was mailed (other than the fact that the 2 cent stamp wasn't in use until March of 1869). We couldn''t even be certain that this was an example of the circular rate of postage.

But, the contents give us a confirming year date (1869). The circular was printed in Richmond, for a Richmond firm - so it was likely mailed from Richmond. And, of course, the envelope was unsealed and held... this... a circular! Tadaaaaaaa!

Even better, the clues the contents give us match up with the limited clues the envelope provided. When the content and the cover confirm each other like this, it makes the story you can tell with your postal history item that much stronger.

Now we can have a little bit more fun and do some searches to see if there are advertisements that confirm the existence of this business during the time period we're looking. Sure enough, the Valley Virginian, published in Staunton, Virginia in November of 1869 includes an advertisement for the same Powhaten Rawbone Super Phosphate.

So, all of this has been fun. But, that's not what initially got my attention.

What interested me is the farming history that came with the postal history.

One thing that stands out is how our language has changed over time. If I were to use the word "manure" right now...

Ok... stop laughing. This is supposed to be a serious blog post.... you too. Yes, you! No more laughing. I warned you about the "poo thing" with the title of the blog post. You should have known it would come to this!

Ahem.

So, if I were to use the word "manure," you would probably be thinking about animal manure. But, apparently, in 1869, any sort of fertilizer could be construed as "manure." For those of us who have done some gardening or growing, we might recognize the "raw bone super phosphate" as "bone meal," which is known to be an excellent slow-release source of phosphorous for growing plants.

I recognize that some people are a little squeamish with the idea of using ground up animal bones as a soil supplement, but you need to consider the relative resource efficiency of using bone meal versus other sources of phosphorous. Most farms included animals in their operations, some of which were raised for meat. Rather than simply discarding the bones, they could be used by being ground up and placed back into the soil so the cycle of life could continue. The goal of companies like this was to make the bone meal "soluble" so it be more readily available for uptake by plant roots.

The other popular fertilizer that provided phosphorous in 1869 was "Peruvian guano" which was the harvested excrement from seabirds and bats. This pamphlet compares their product by noting that what they produce is much more "favorably priced" than the more expensive guano that had to be shipped up from South America.

Currently, most of our phosphorous fertilizer is synthesized from mined phosphate rock, which is not a good thing since it is typically strip-mined and the process of creating the fertilizer results in a significant amount of hazardous waste by-product. Maybe we need Powhaten to get their business running again? But, then again, I can't say how they treated the raw bone to create their fertilizer either.

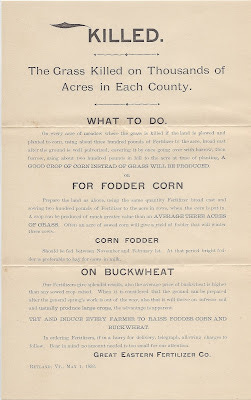

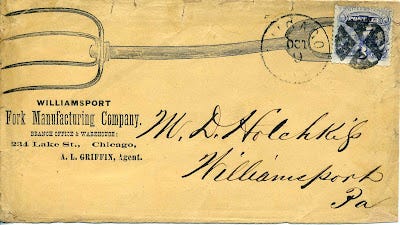

The second item I would like to show today is also an envelope that qualified as a printed circular. However, this envelope was mailed in 1893 and simply qualified as a third-class mail item - printed circulars were now just included with everything else that fell into this class. The postage rate was 1 cent for every 2 ounces in weight (1879-1925).

Before going into the farming side of things, the design at the top left on the envelope bears a little scrutiny. For those who don't know, collectors often refer to this sort of design as a corner card which often served both as advertisement and a return address.

I found it interesting that a company, based in Rutland, Vermont, would choose Napoleon as a sort of "mascot" or "brand identification." Other paper advertisements from them in the 1890s show similar designs. Of course, they are trying to set themselves apart as leaders in their field and boldly say so with the words "I lead" next to Napoleon's head.

The words "Napoleon. Friedland. 1807" make it clear that they are referencing a key event in Napoleon's military history. The Battle of Friedland was the event that persuaded the Tsar of Russia to enter into the Tilset peace agreement, which "split Europe into French and Russian spheres of influence and reduced Prussia territory significantly." (this last statement taken from the linked article)

I understand the idea of trying to establish that your company is a leader in the field, but I am not sure how appropriate it is to say that you are the Napoleon of Fertilizer... look at us, we are the "Emperors of Poo!"

There were multiple copies of the same promotional circular in this envelope. This is very interesting to me because that indicated that I was likely looking exactly at what the recipient saw when they opened this envelope. It gives me a view into how one company sought to expand sales by mailing promotional material to people on their mailing list, hoping they, in turn would pass information on. Given the contents of this envelope, I would say it didn't work in this particular case.

You can also notice that the contents are dated May 1, 1893 - which is a confirming date to go with the May 4, 1893 postmark from Rutland.

There are two points regarding the content of this document that strike me, as a grower of food. The first is the concept that grass is undesirable and of little value. After all, if someone decides to rely on perennial pasture, the Great Eastern Fertilizer Company might not have product for you. So, it made sense for them to promote tillage and the application of their products for annual crops, such as corn and buckwheat. But, even if the promotion made sense for the fertilizer company, we have learned over time that perhaps grass pasture has much more value than they portray here (in my opinion, grass pasture has more value, especially now that it is so scarce in states like Iowa - but that's for another day).

Second, the simple fact that buckwheat is listed on par with feed corn is telling. In current times, buckwheat is touted by vegetable growers as an excellent short season cover crop. The idea of growing buckwheat for flour production does not seem to hold much sway anymore, even though buckwheat is a quick grower that could be used even if a season started extremely wet and didn't allow entry into a field until later.

As a final note - the New York Agricultural Experiment Station regularly produced reports that outlined their own analysis of products offered by companies like this one. The 1897 report linked in the prior sentence states that 193 manufacturers of fertilizer had registered with the station as required by law. With these manufacturers there were 1900 different "brands" or products. For claiming to be a leader, the Great Eastern Fertilizer Company was found to have levels of active fertilizer ingredients below their guaranteed levels in three of their twelve products being reviewed.

One could say they might have been a full of.... poo?

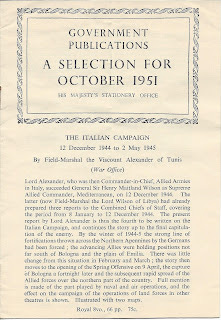

Here is one more that I wanted to share today, and it comes from Great Britain and is mailed to the United States. This item would also have qualified for discounted postage rates, but I have not had time to identify the particulars of this rate - but that's not what I wanted to show you!

This item is an open-ended paper wrapper that holds a pre-printed circular advertising publications put out by H(is) M(ajesty's) Stationery Office. And, it feels to me that they were very, VERY interested in making sure you know that.

The address is pre-printed on the wrapper at bottom left (Shepherdess Walk in London). There is a purple handstamp applied for the HMSO. And, even the contents have "His Majesty's Stationery Office" printed and sticking out of the end at the left. I think we get the point!

The smudged purple handstamp reads "printed and published in Great Britain." Once again, this seems a little redundant. But, if it seemed important to them and they wanted to pay someone in their office to stamp every copy being mailed out with this... it was their choice. Right?

The other interesting sidelight for this piece of mail are the holes that you can see on the postage stamp. Look closely and you might see that the holes punched into the stamp are the letters "H M S O." That probably should not surprise us since HMSO is EVERYWHERE on this item. But, these letters on the stamp actually served a different purpose.

Punched designs in stamps are called perfins and their purpose was to prevent the pilferage of stamps purchased for use by a company or government office. If you think about it, the HMSO must have mailed a significant amount of material on a regular basis. Rather than go to the post office every day and pay for postage stamps, they probably purchased them in bulk. But, if there were a whole bunch of stamps lying around, it is possible an employee might decide no one would miss a sheet or two if they wanted to take some home and use them for themselves.

To prevent this, the HMSO effectively personalized the stamps by putting in these perfin designs. If someone did take a few sheets it wouldn't be hard to identify where they came from if that person tried to use them on the mail.

If we look at the first page of the enclosure, we might conclude that this is something that was mailed out from the HMSO every month (this is the October 1951 edition) - so it was not a small undertaking. In a real way, it makes my writing a weekly postal history blog seem small by comparison. At least I don't have to print out a bunch of copies, fold them, put them in wrappers and mail them all out!

The publications being summarized in this circular cover a wide range of subjects - but to keep to the topic at hand, you will find that there are even some publications on agriculture, including one dedicated to potatoes.

This is where I have to stretch a little to maintain a connection to the topic at hand... poo. There is actually no direct mention of fertilizer, manure, bone phosphate or guano. Instead, there is a quick mention that the potato brochure includes information on soil preparation.

Well, sure! Soil preparation often includes managing fertility! Let's go with that!

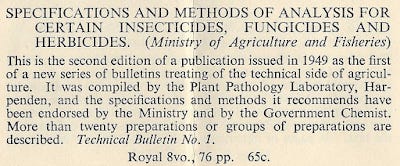

What actually drew my attention to this particular item was the publications on insecticides, fungicides and herbicides. In 1951, these tools were truly beginning to gain prominence - in large part because of industry's desire to sell product. I find it interesting to read the description of this part of the circular:

Clearly, it is a new topic for them. The simple mention of endorsement by the Ministry and the Government Chemist implies a feeling that they need to justify the validity and usefulness of this publication. And, given what I know now, I wish they - and other agencies like them - had not been so successful in achieving general acceptance for these products.

Well, thank you for joining me this week! I hope you were entertained and, perhaps, learned something new. But, you'll have to excuse me. I've got to grab my pitchfork and clean out the chicken coop.

Have a great remainder of your day and good week to come!