Welcome to Postal History Sunday. This post was originally published on November 20, 2022. In honor of the 200th PHS post, I selected two of my favorite articles from the past to share during the week as a part of the celebration.

Put on those fuzzy slippers, grab a favorite beverage, and enjoy!

Sometimes the attempt to write a fresh post every Sunday can feel pretty daunting. This is especially true if the planned post topic no longer works - for whatever reason. And, of course, that is essentially what occurred this week. The initial plan was that we would be attending Chicagopex (a stamp/postal history event) for at least part of the weekend. I figured I would do something I had done in the past and report on what was going on there. I expected I would take some pictures, make some observations, and otherwise tell everyone what was going on.

Well, a funny thing happened on the way to the show... Ok - not funny. We received a call after we had driven for over three hours that the people who were going to tend the farm for us had been in a car accident (they're fine) and could not take care of things. So, we sat in a Casey's parking lot for about 45 minutes trying to find alternatives. In the end, we turned around and here we are - back at the farm and in "make the best of it" mode.

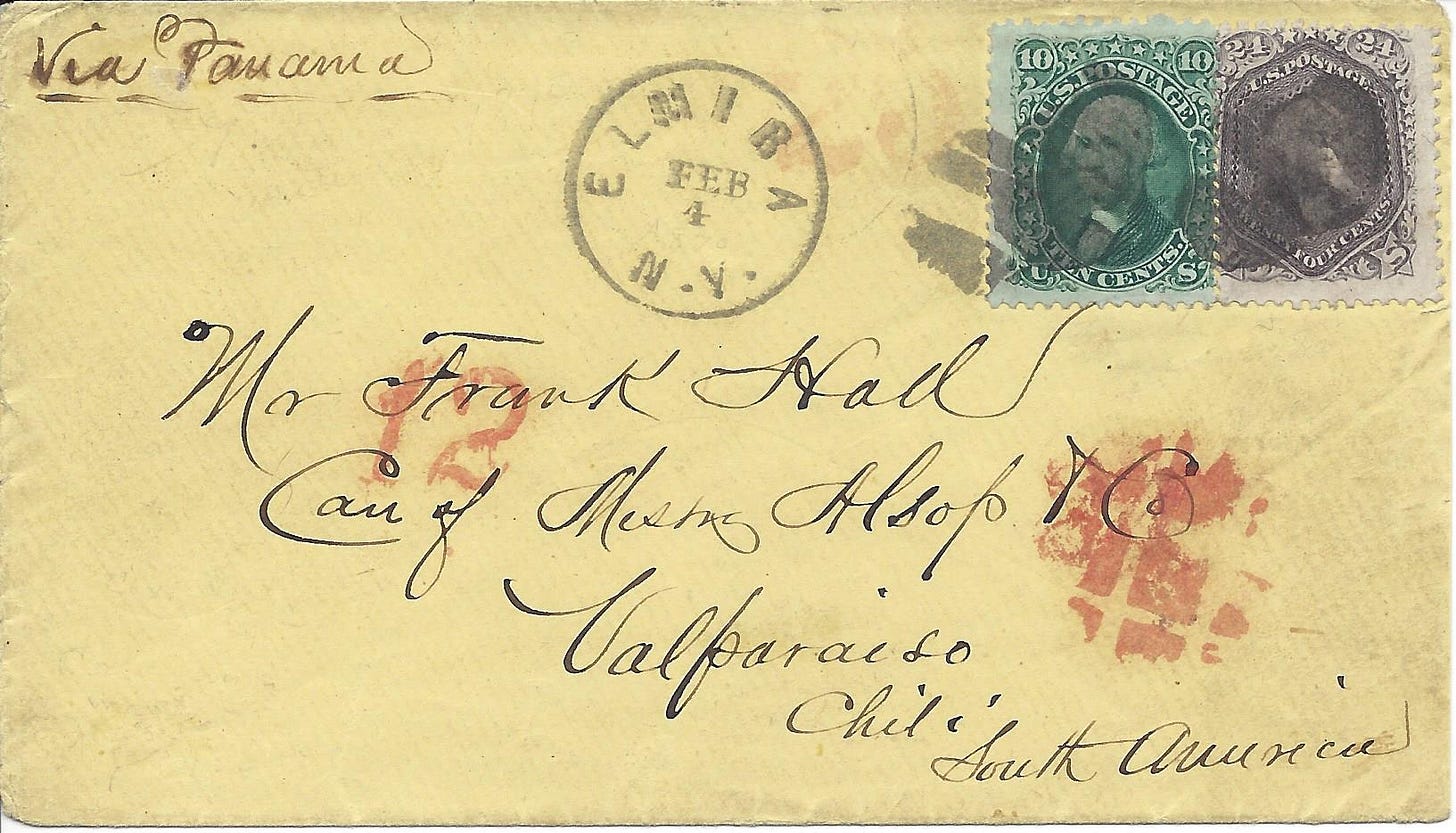

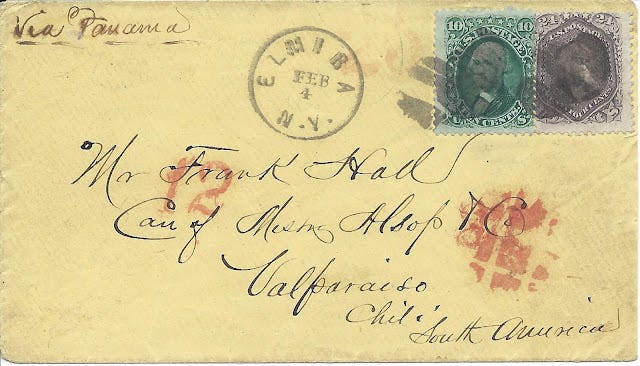

So, I'll move up the time table on my exploration of the cover shown below. It attracted my attention because of the two bold, red markings on the front.

The Puzzle

All of the hints about the story this envelope can tell are visible to you right now. There are no contents. There are no dockets other than the "via Panama" at the top left. There are no markings on the back-side (the verso) of this envelope. This is it.

The letter was mailed and postmarked at Elmira, New York on February 4 and it was sent to Valparaiso, Chile for a Mr. Frank Hall. He had apparently arranged for his mail to be sent "care of Messrs Alsop & Co." Thirty-four cents of postage appear at the top right which was apparently accepted as sufficient pre-payment.

That leaves us with three more markings that have something to tell us.

We'll start with the easiest one to see and explain. The red "12" is the amount of the collected postage that was to be given to the British for postal services rendered. In order for a letter to get to Valparaiso, Chile, from New York, it had to be carried first to Panama. It would then cross the Isthmus until it was put on board a steamship that was under contract with the British Post Office to carry mail to South American ports. At the time this letter was in the New York City post office, we must have been under an agreement that British service would cost 12 cents.

Then,we come to this mess. If you look carefully, you can see the number "24" in red that had apparently been put on this envelope. Someone must have decided this was wrong and they covered up that marking as best they could with a heavy waffle-like cancellation.

If you take a moment, you might be able to notice that the red ink for the "24" is slightly different than the ink for the "12" and the waffle marking. But, the "12" and the waffle seem to be the same ink. That tells us the "24" was applied at a different time than the other two.

And then there's this. Look carefully, do you see another marking in red ink here?

Even if you can't see it, there is a marking there that is the number "25." This marking was applied in Chile. But, how did I know that?

There were other questions that occured to me when I looked at this cover. First, this cover looked very much like a regular 34-cent rate cover to Peru. But, I was not certain that 34-cents was the postage rate applied to this letter. Was I right and was there a way to prove my theory? For that matter, what year was this letter sent?

Ah... puzzles can be so much fun!

What was the "25" for?

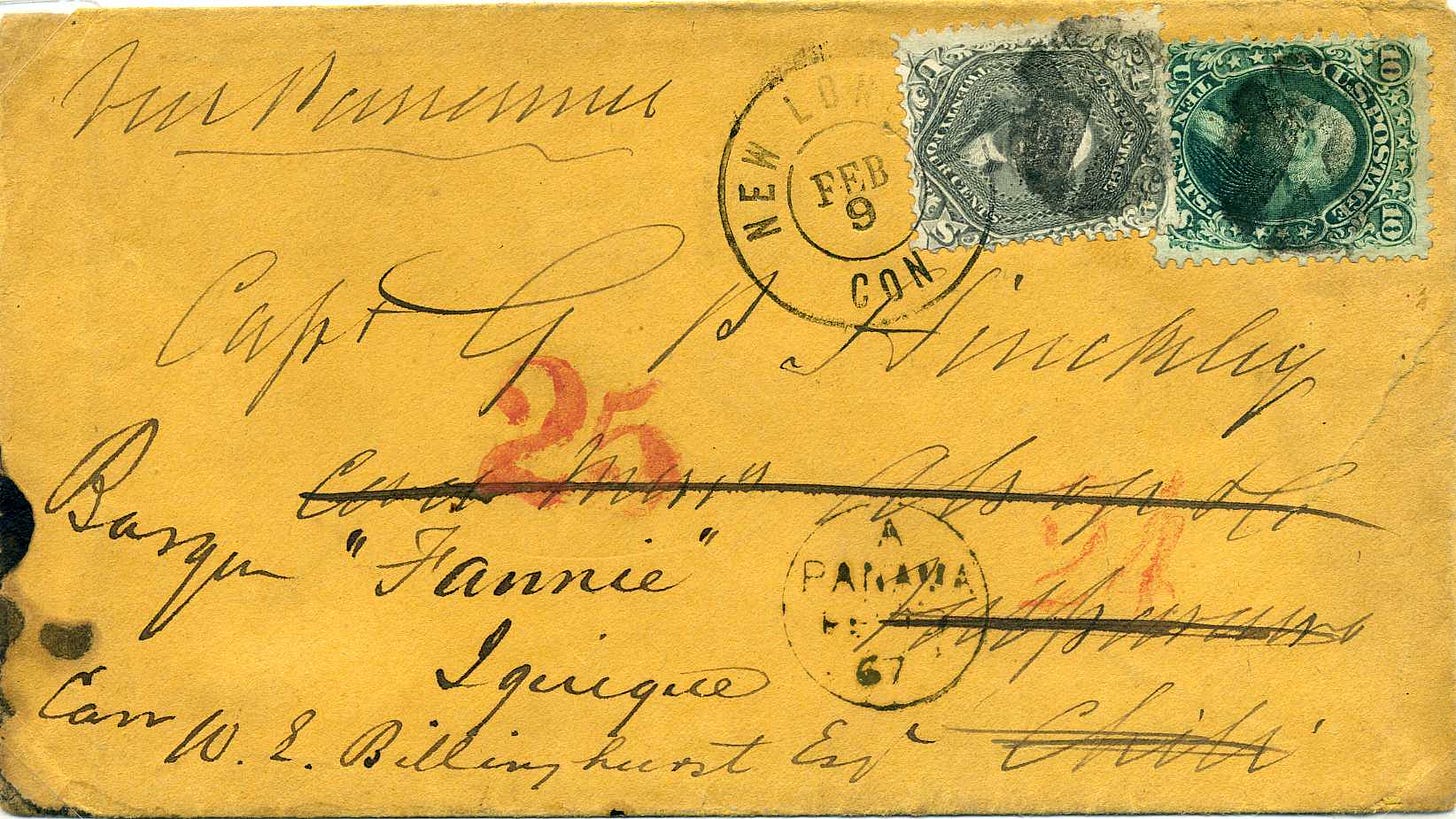

I'm going to start with another envelope that did not present so much of a mystery for me to solve. This one was sent from New London, Connecticut in 1867. The recipient was a Captain Hinckley and his ship must have been the barque "Fannie." His mail was also sent to Messrs Alsop & Co, which would have been the most common location for United States ship captains or US citizens to have their mail sent if they were visiting Chile.

And there is a big, bold '25" right in the middle of the cover! As I mentioned before, the marking was applied in Chile and the slant of the numeral "5" was normal for this marking. Unfortunately, it is also pretty common for it to be very lightly applied, so it can easily be missed.

Foreign mail to Chile could only be pre-paid to the point of entry into the country. Chile charged an incoming foreign mail fee equivalent to 5 centavos (July 1853 to December 29, 1874). In addition to the incoming mail fee, incoming mail required two times the domestic internal rate (10 centavos) for a total charge of 25 centavos collected from the recipient at the point of delivery.

How did mail get to Chile?

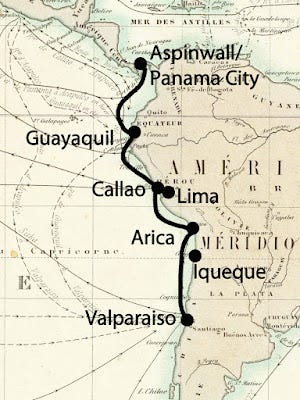

Mail for South America that had an origin in the eastern half of the United States would typically go to the exchange office in New York City. From there, it would take a steamship owned by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (often called the Aspinwall Line) to Chagres. Chagres was located on the Gulf of Mexico side of the Panama Isthmus and was often referred to as Aspinwall at the time this letter was sent. Mail would then cross the Isthmus and board a British steamship at Panama City.

The British steamships were run by the Pacific Steamship Navigation Company (PSNC) and they made stops along the west coast of South America. There were stops in Ecuador, Peru, and, finally, Chile.

The second cover has a black, circular marking that was put on the cover in Panama City by the British postal clerks. This particular cover was handed over to the British agents on February 19, according to that postmark. A typical steamship schedule by PSNC would have this letter arriving in Valparaiso at or around March 9.

On average, it might take nine or ten days to get from New York City to Panama City and another seventeen or twenty days to get to Valparaiso. If you would like to learn a bit more about the route from the east cost to the west coast via Panama, there are numerous sources you could try. Among them might be John Kemble's 1938 paper titled The Panama Route to the Pacific Coast: 1848-1869. Or if you want something contemporary to this period, you can read Isthmus of Panama: History of the Panama Railroad and of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company by Fessenden Otis, published in 1867.

How much did it cost to mail a letter to Chile?

The only postage rate for mail from the US to Chile during the 1860s was a 34 cents per half ounce rate that was in effect from December of 1856 until early February of 1870. And since I concentrate the most on the 1860s, that is what I am most familiar with. The 34-cent rate was broken down into two parts: 10 cents to cover the US postage and 24 cents for the British carriage from Panama City to Chile.

But the price governments were willing to pay steamship companies to carry the mail was declining in the 1860s and early 1870s. As a result, the British reduced their own postage rates to destinations on the west coast of South America by 6 pence (equivalent to 12 US cents), making this change effective on January 1, 1870. They would not pass on those savings to US postal customers until February 15, 1870. As of that moment, the US only had to pay 12 cents, instead of 24 cents, to the British, and they were able to lower the postage rate for US customers from 34 cents to 22 cents (Feb 15, 1870 - June 1875).

Answers to the puzzle

So, we return to our first cover so we can provide what I think is the most probable explanation for this particular letter!

A postal customer in Elmira, New York went to their post office on February 4th, 1870, and gave this letter to the clerk, probably paying that clerk 34 cents to pay the, then current, postage for a letter to Chile. The clerk or the postal customer put 34 cents worth of postage stamps (a 10 cent and a 24 cent) on the envelope and the clerk dutifully postmarked the letter and cancelled the stamps so they could not be used again.

The letter was then put in a mailbag so it would go to the foreign mail exchange office in New York City. The docket "via Panama" told people at the exchange office that the letter should get on a steamship to go to Panama, rather than overland to San Francisco and then down to Chile. The PMSC steamship named the Henry Chauncey was due to leave New York's harbour on February 5th. So, as long as the letter got to the New York foreign mail office in time, all should be well.

The foreign exchange clerk in New York put a "24" marking on the envelope, just like they had been doing for every letter to Chile since 1856. And then they realized that it was too late to get this letter to the Henry Chauncey, it left the Port of New York without this item.

The next steamer scheduled to leave New York City for Chagres was the Alaska on February 21, six days after the postage rate was to change from 34 to 22 cents. And, once that happened, the amount of postage to be passed from the US Post Office to the British would only be 12 cents.

So, at some point, the clerks in the New York Foreign Mail Office used this waffle grid to cover up the old "24" credit markings and they replaced it with the "12."

Why? Well, they didn't want to send the British any more money than the postal agreement was asking for, and this letter did not sail on a British ship until AFTER the rate had changed.

So, my final answer is summarized as follows:

The letter was mailed when the rate was 34 cents per half ounce.

The New York exchange office marked it as a letter mailed at the 34 cent rate by putting a "24" on the cover.

It arrived in New York too late for the ship departing on Feb 5

The rate changed to 22 cents on February 15

The New York exchange office marked it as a letter mailed at the 22 cent rate by covering the "24" and putting a "12" on the cover

The letter traveled on the Alaska to Chagres at the Isthmus, leaving February 21

The probable arrival of this letter in Valparaiso was some point after March 20

That's my story and I am sticking to it!

Outstanding questions (edited 6/17/24 with some answers!)

At the point I originally wrote this article, I did not have actual departure or arrival dates of the Henry Chauncey or the Alaska. While I have not yet hunted down the arrival dates for those ships, I can now provide some clippings that helps us view the New York departure times.

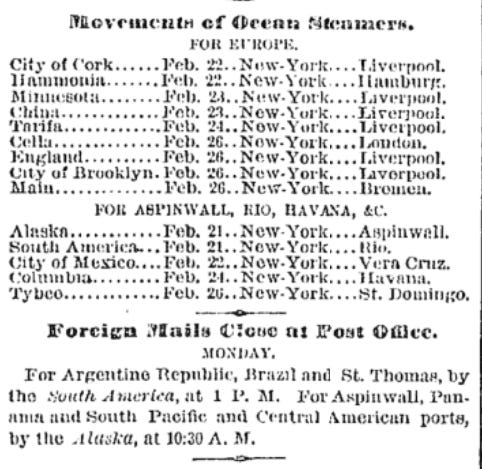

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company, like many other major ocean going lines, were regular advertisers in the New York Times. This ad very clearly states that PMSC ships departed New York on the “5th and 21st of each month.” It also clearly indicates that the Henry Chauncey was scheduled to depart that day (Feb 5).

The Marine Intelligence concurs that the Henry Chauncey was departing on the 5th. And, interestingly, it shows the mail to Panama closing at 10:30 AM on that Saturday (also the 5th). It attaches that mail to the Arizona erroneously since every other reference for the PMSC is for the Henry Chauncey.

Our letter was mailed on the 4th in Elmira, New York, so it is theoretically possible that it could have reached the New York Foreign Mail Office prior to 10:30 AM the next day for processing. However, it seems just as likely that it did not get there in time. So, it seems quite safe to say the letter simply did not get there befoe the closing of the mails to Panama and it had to wait for the next sailing - which, according the the advertisement, would be the 21st.

The New York Times for February 21, shows the mail for Panama leaving on the Alaska and the marine intelligence concurred with that information.

I have yet found the time to locate arrival dates and I also do not have the departure/arrival dates of the PSNC ship that left Panama for South America. So, if anyone has information on those, I would be grateful. Otherwise, it will simply wait until I have time to dig a bit more.

Also, I am willing to hear any arguments that might indicate that my conclusions are wrong - though I don't think I am. However, it makes it pretty hard to learn if I won't entertain the possibility that I am in error in the first place.

Bonus Material

Let's go back to the second envelope I featured for a couple of interesting tidbits that you might enjoy!

While I was unable to find much on Capt Hinckley or the barque (bark) Fannie, I was able to locate some information about one person who handled this letter on behalf of the good captain.

This letter was initially sent to Alsop & Co in Valparaiso, but they sent that letter on to W.E. Billinghurst in Iquique, which was in Peru at the time this letter was sent (1867). We can assume this letter caught up to Capt Hinckley at Iquique since there doesn't appear to any more travels recorded on this envelope.

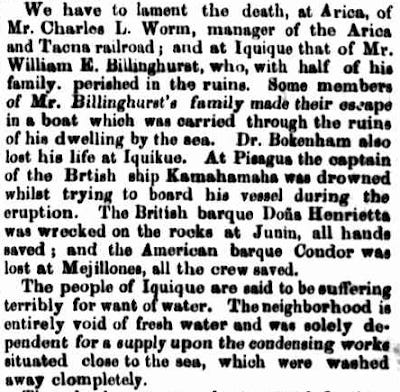

Mr. Billinghurst was listed as a shipping agent for Lloyd's in Iquique during the 1860s and was, like many who worked as a shipping agent, also the representative for many other concerns. Anyone involved in trade, especially of Chilean saltpeter, had likely heard of him. So, it might not be surprising to hear that his demise was specifically noted in newspapers throughout the world.

I found an article in the Brisbane Courier of Oct 13, 1868 (page 3) that explains the fate of Mr. Billinghurst (about 15 months after handling this letter). An extremely large earthquake, estimated today as having been somewhere from 8.5 to 9.3 on the Richter Scale, was centered around Arica, north of Iquique. This would place it among the most violent earthquakes recorded. That earthquate caused tsunamis that impacted many of the ports to the south, including Iquique.

If you have interest in reading about the severe earthquake activity in South America during 1868, here is a contemporary report from Harper's Monthly from 1869 that might give some insight.

Iquique, despite being located in a desert region, was a port of prominence because that desert had strong deposits of sodium nitrate (Chilean saltpeter) - used for fertilizers. Prior to the late 1860s, the Chinchan islands off the coast of northern Peru had been mined for guano that could be exported worldwide as a fertilizer. With those deposits rapidly being depleted, attention was shifting southward to the Atacama desert - and to Iquique - as the primary port of departure for ships laden with Chilean saltpeter as a fertilizer product. In 1867, nearly 116,000 tons of saltpeter were exported by Peru. This amount declined the following year, likely due, in part, to the earthquakes.*

If you would like to learn more of the Atacama desert, I did come across a book by Isaiah Bowman titled Desert Trails of the Atacama, published in 1924. I started reading parts of it and then realized I needed to finish this Postal History Sunday post! At the very least, I put the link here so I can look at it in the future if I would like!

*Greenhill & Miller, Peruvian Government and the Nitrate Trade, 1873-1879, Journal Latin American Studies, pages 110-111

And there you have it! Another Postal History Sunday in the books! I hope you enjoyed this journey and that maybe you learned something new.

Thank you for joining me. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest