Welcome to Postal History Sunday. This post was originally published on August 14, 2022. In honor of the 200th PHS post, I selected two of my favorite articles from the past to share during the week as a part of the celebration.

Put on those fuzzy slippers, grab a favorite beverage, and enjoy!

So... what have we here?

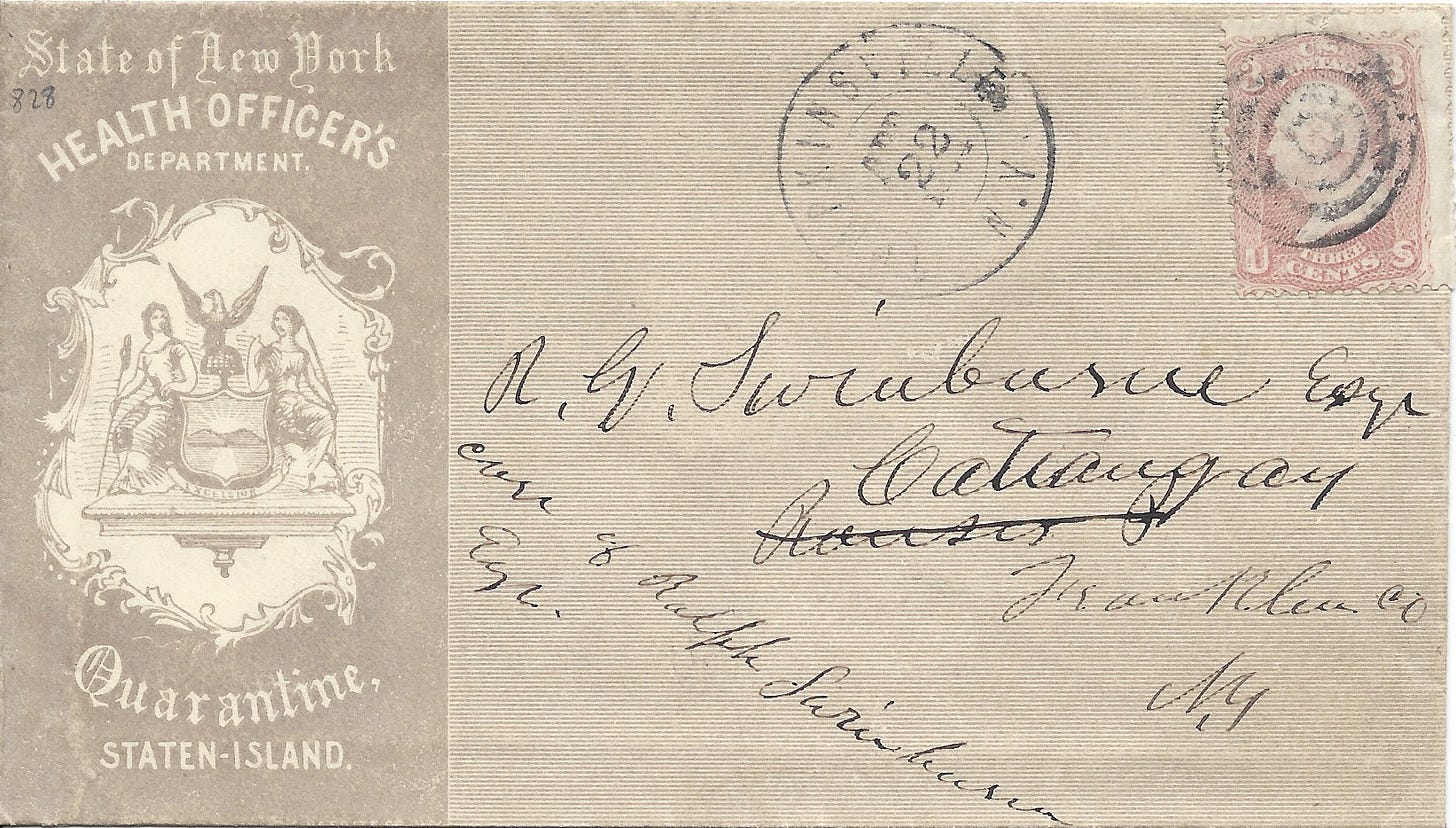

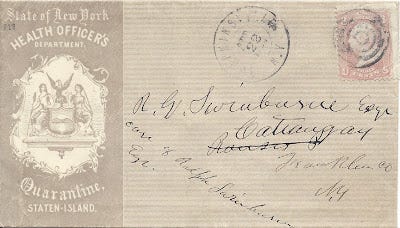

Today's featured item is an envelope that has a fancy, pre-printed design for the State of New York Health Officer's Department. Specifically, this envelope advertised that it came from the Quarantine on Staten Island. This design alone speaks to a significant story related to the immigration of people to the United States.

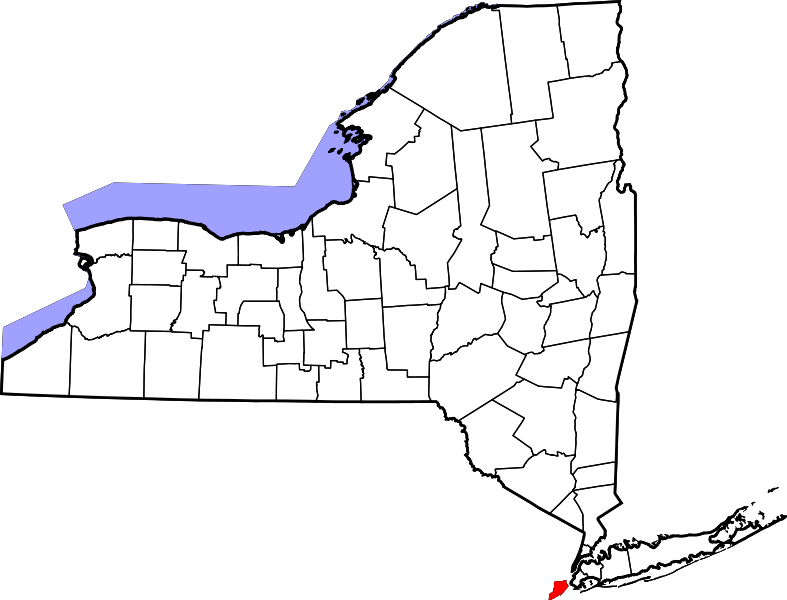

The postal history angle is actually pretty simple this time around. The three cent stamp pays the postage for a letter mailed within the United States that weighed no more than a half ounce. According to the postmark, the envelope entered the US mails at Tompkinsville, New York on April 22, 1864. Then the letter found its way to Chateaugay, New York in Franklin County in the northeast portion of the state, near the Canada border.

The cover is addressed to R.G. Swinburne, care of Ralph Swinburne at Chateaugay. If you look carefully, you can see that the person writing this address crossed out "Rouses," which would have become "Rouse's Point" in New York if they had continued writing. The envelope itself has no contents, but I can tell you that this item was written by a Dr. John Swinburne, who was sending something to either a brother or a nephew.

Before we go further, let's take a look at a couple of maps so we can orient ourselves a little bit before we get to the fun stuff.

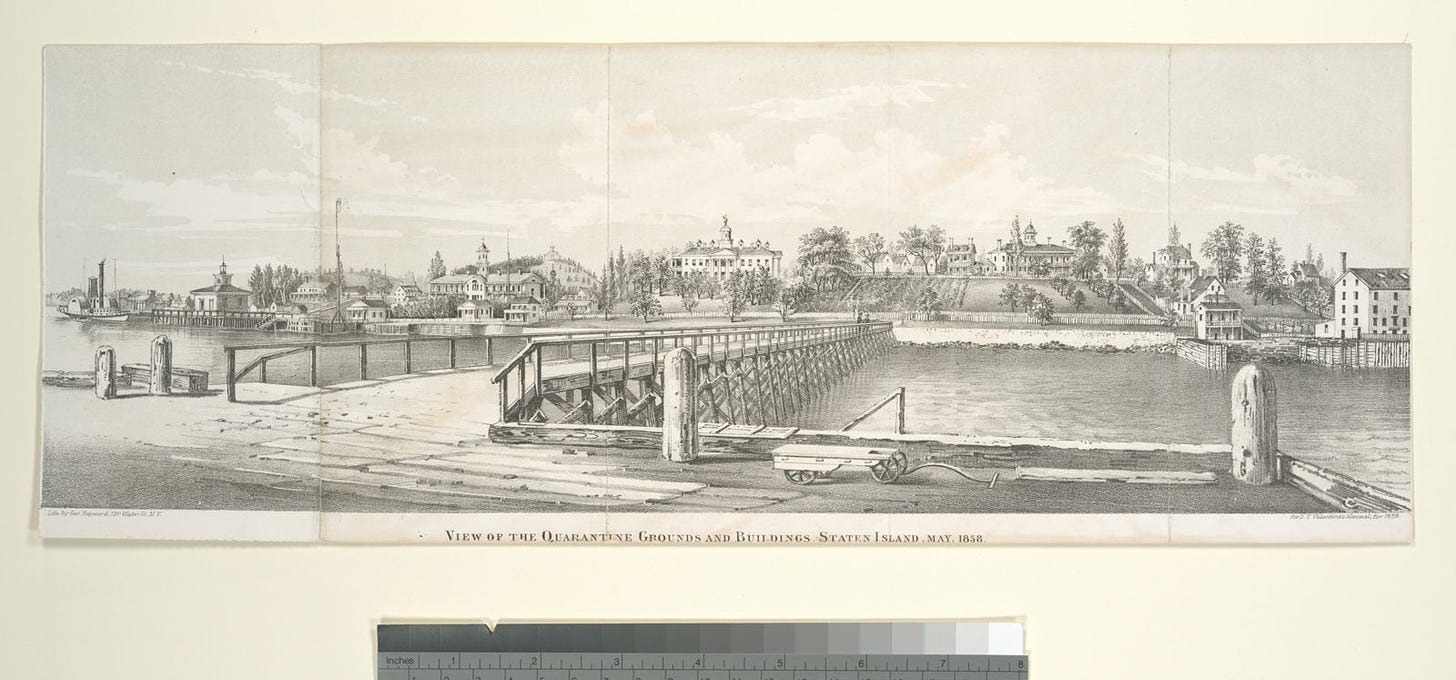

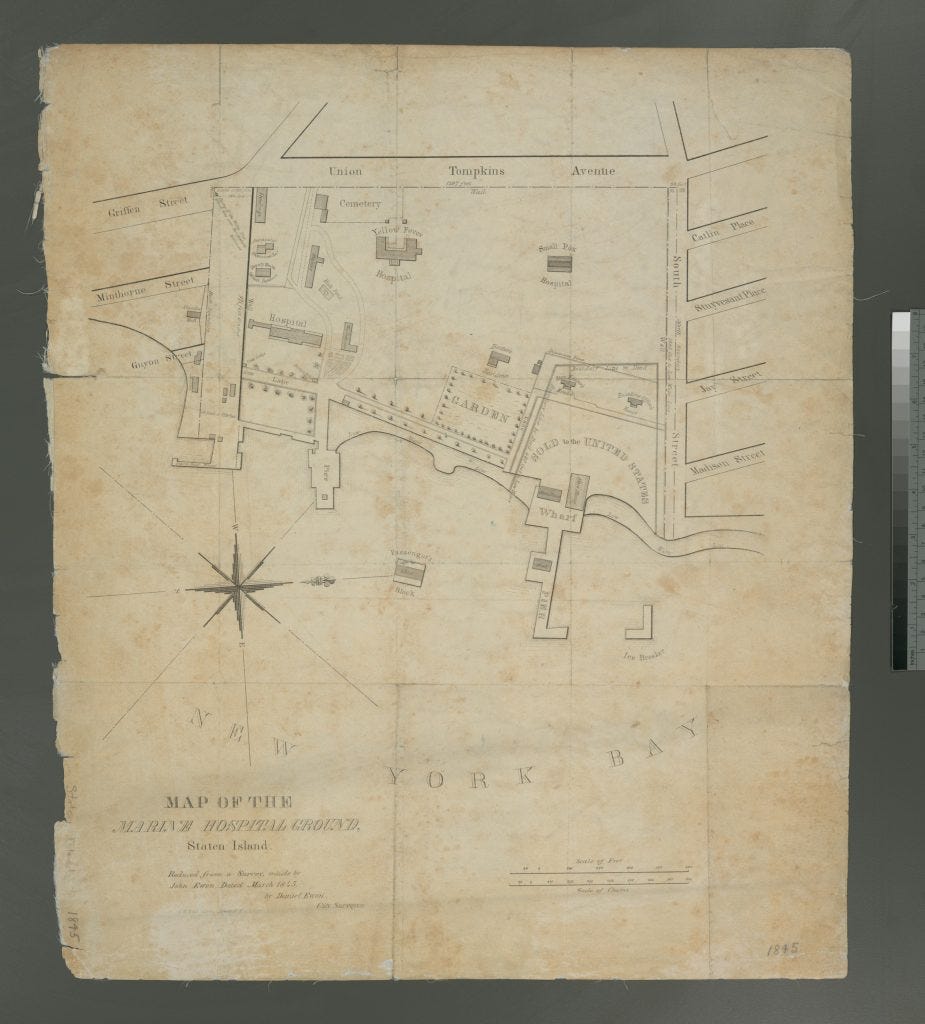

Much of our story focuses on the area shown on this second map (from 1873) that shows the grounds of the "Quarentine" (sic), an area that would soon appear as a privately owned property with multiple wharves and warehouses in maps from the 1880s.

This, of course, leaves us with the question - why do I find all of this so interesting? Read on, and maybe you'll also agree that there is a good story behind this old envelope.

The quarantine on Staten Island to 1858

The Harbor of New York has a long history of using quarantine in an attempt to limit the spread of disease brought to port with incoming travelers and immigrants. Our story starts with the quarantine grounds and buildings located at Tompkinsville, New York on Staten Island. The state legislature designated this location for quarantine and by 1801 it was fully established as such. A hospital was built at that time (which became known as the Marine Hospital), a wharf was constructed, and an area was designated for anchoring ships that were under quarantine.

By the time we get to the 1840s and 50s, there were multiple buildings serving as hospitals, including one dedicated to Yellow Fever and another to Smallpox on the 1845 map shown below.

This article on the Whaling Museum site provides an excellent summary of the quarantine process:

By 1846 all ships coming into New York Harbor had to anchor off Staten Island for quarantine inspection. The ships were boarded and if any signs of disease were found all the passengers were taken to the Quarantine Hospital on Staten Island which was opened in 1799 and called the Quarantine. First-class passengers were taken to St. Nicholas Hospital at the Quarantine and steerage passengers were taken to smelly, overcrowded bunkhouses [where they were] stripped naked and disinfected with steaming water. [1] The ship then had to remain in quarantine for at least 30 days and sometimes as long as six months. There were as many as eight thousand patients in the hospital in a year. It was very dangerous work for the staff and funeral expenses for employees was a category in the accounting books.

An article in Harper's Weekly titled "The Forgotten of Ellis Island," provides an excellent summary of the history of the Quarantine for the New York Harbor that may also be of interest to you. (Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization, Vol. XXIII, No. 1184, Sep 6, 1879)

It is at this point that we need to remind everyone that Staten Island was NOT an abandoned island that served the sole purpose as a quarantine location. There were multiple communities where people made their homes, farmed and worked, including Tompkinsville. Some of these people worked at the Marine Hospital, and a significant part of the population were fearful of the possible spread of disease from the Quarantine to the rest of the island population.

People were raising families and living their lives. So, they were less than happy to have this facility in their back yard. And, of course, many of the wealthier landowners were less than pleased by the impact the quarantine site had on land values.

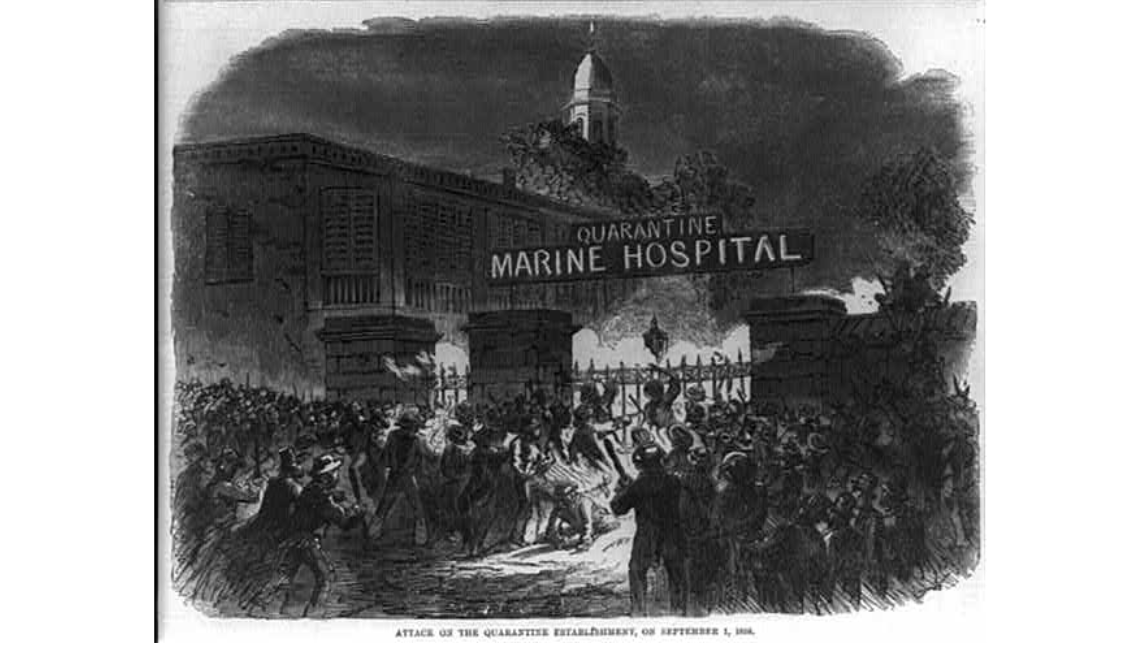

Rioters burn the Quarantine

On September 1, 1858, a mob of armed individuals burned down many of the buildings at the Quarantine, leaving only one active hospital building. The local fire department, sympathetic to the cause of the rioters, claimed that their hoses were cut as they stood by and watched the fires burn. Fortunately, the rioters, for the most part, gave warning and encouraged workers and patients to vacate prior to the planned arsons.

Harper's Weekly reported on September 11, 1858 that a pamphlet was circulated on the following day that read as follows:

A Meeting of the Citizens of Richmond County, will be held at Nautilus Hall, Tompkinsville, this Evening, Sept. 2 at 7 1-2 o’clock, For the purpose of making arrangements to celebrate the burning of the Shanties and Hospitals at the Quarantine ground last evening, and to transact such business as may come before the meeting. September 2d, 1858.

The riots on September 2 were also not a surprise to those at the quarantine as they had been warned that there were intentions to burn the rest of the buildings, including dwellings, to the ground. In fact, those living in various staff quarters on the grounds removed their furniture and belongings and stood by them to protect them when the rioters returned for a second night.

Most of the healthy individuals who were under quarantine had been moved during the day, but there remained some staff and patients at the remaining hospital (identified as the "Female Hospital" though I am not certain which one that was). These individuals were evacuated prior to that building going up in flames, but they were not far away. Medical personnel poured buckets of water on the sick to help keep them cool while the building burned nearby. (from Stephenson, Kathryn. "The quarantine war: the burning of the New York Marine Hospital in 1858." Public Health Reports, Jan-Feb, 2004)

If you want to read the details of the motivations and the events, I strongly recommend you read that paper.

Now what? Where's the Quarantine?

It was at this point that we might be tempted to ask some questions about the envelope that started this whole Postal History Sunday. If everything was burned down, did they rebuild in the same location even after the local populace had made their feelings about it known so "eloquently?"

Stephenson reports that about 60 US Marines were assigned to protect particular buildings (but nothing else) on September 2 (probably the fenced in area at the bottom right in the 1845 map). It is possible this is where administration for the Quarantine continued after the 1858 riots, but I have been unable to confirm that.

The short answer was that they did not rebuild at Tompkinsville. Instead, they moved most of the quarantine to a "floating hospital" (the Florence Nightingale) that was dedicated to this purpose. Some sources suggest that the steamships Falcon, Empire City and Illinois all served this purpose when needed. But, it is unclear to me if they were used between 1858 and 1864.

What is clear is that the quarantine protocols for the New York Harbor were now in disarray and the Quarantine was provided with little in the way of resources. The event of the American Civil War was also diverting attention away from this issue. But the specter of diseases, such as Yellow Fever, led to the General Quarantine Act of April 23, 1863, which established the office of Quarantine Commissioner, authorized the building of new facilities, and encouraged new procedures for quarantine.

This is where we find ourselves in 1864, the year our envelope is dated.

The Quarantine is dead, long live the Quarantine!

It is at this point that Dr. John Swinburne enters the picture. The New York State Senate, according the New York Herald on March 20, 1864, indicated that they would approve the appointment of Swinburne to the post of Health Officer for the Port of New York. They would do so, as long as Governor Seymour submitted Swinburne's name. This was done and Swinburne was approved to replace Dr. Gunn at this post with a unanimous vote of approval.

It is at this point that I bring you back to our envelope and remind you of the date it was sent (April 22, 1864) and of the addressee, R.G. Swinburne. This makes it likely that this letter was written and sent by Dr. John Swinburne just one month after being assigned to the post as Health Officer.

Apparently, Swinburne's appointment highlighted a rare occurrence (unanimous approval), with Gov Seymour and the New York Senate rarely seeing eye to eye (different political parties). And, the track record for Dr. Swinburne as Health Officer from 1864 to 1870 provides evidence that his selection was an excellent choice. The report from the Health Commissioners at the end of 1864 made note of the fact that Swinburne had been left with minimal resources, a leaky hospital ship in need of dire repairs, and no infrastructure to speak of after the 1858 riots. Yet, his competent leadership resulted in no cases of Yellow Fever escaping the port to infect the city's populace.

Swinburne put in place procedures and facilities that addressed both the need to prevent the spread of disease and to effectively care for those who arrived at port with an illness over the next six years. The Health Commission found his year-end reports to be so valuable that, rather than presenting the traditional summary, they recommended that the entire report be presented as they "contained much valuable information."

Perhaps one of the most notable accomplishments during Dr Swinburne's tenure as health officer was the creation of two man-made islands that included appropriate hospital facilities to treat those who arrived at port with an infectious illness. The larger island was named Hoffman Island (after the mayor of New York City and then governor of New York). The smaller island was initially named East Bank, and then Dix Island - but it was eventually named Swinburne Island. Swinburne Island was also referred to as "Lower Quarantine" and was completed in 1870. Hoffman Island was, not surprisingly if you are paying attention, called "Upper Quarantine" and was completed in 1873. Both are now National Recreation Areas and no longer serve as quarantine locations.

How do we know Swinburne sent this letter?

It certainly would be fair to question how I come about making the claim that this letter was sent by Dr. John Swinburne. So - let's see if I can adequately defend that assertion.

First, the letter is addressed to R.G. Swinburne, care of Ralph Swinburne in Chateaugay, New York (which is near Albany). If we look at some of the publicly available genealogy material, we find that Swinburne had brothers named R.G. Swinburne and Ralph E. Swinburne (both older). Ralph is listed as a lawyer in the 1860 Federal Census for Chateaugay, Franklin County, which gives us a strong family connection for this piece of mail.

So, where does the "Rouse's Point" address come from? I found Dr. R.E. Swinburne in the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, vol II, 1892, page 506 (published by the James T White Company in New York). R.E. was Dr. John Swinburne's nephew and the son of R.G. Swinburne and he lived in Rouse's Point. The nephew (R.E.) was ten years old at the time this letter was sent, so it is unlikely that this letter was sent to him. Also, if you look at how the capital "E" in "Esq" is written, you have to conclude that the second initial is not similar.

It makes sense that father and son might leave Rouse's Point for a while to go visit brother and uncle Ralph at Chateaugay and that the good doctor would probably know where to find them - even if he forgot for a moment and started writing out their normal address.

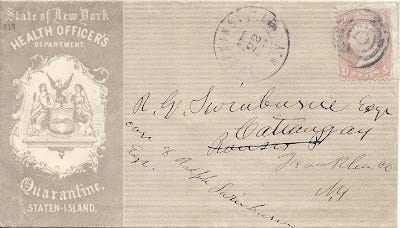

But, here is the icing for the cake. Take a look at the signature, smeared though it might be, for Dr. John Swinburne below.

And now compare that writing to the address panel on the envelope.

Well, folks, I think we've got our man. It seems pretty clear to me that we do have an envelope addressed by the hand of the current Health Officer for the Port of New York in 1864.

Bonus Material

It turns out that Dr. John Swinburne lived a life that was worthy of a book, and that book is titled "A Typical American, or, Incidents in the Life of Dr. John Swinburne of Albany," published in Albany, NY in 1888 (Swinburne died in 1889). If you have interest, you can read this book online. If you decide to do so, I might encourage you to skip the first chapter, which is more editorial than anything, and begin with the second chapter instead.

If you aren't in the mood for something as long as the book, you can try this condensed summary of Swinburne's life put together by the Friends of Albany History. Or, I suppose, you can just read on and see what tidbits I pulled out from my own reading.

Swinburne was a fascinating individual. Much of the reason for the willingness of both political parties to approve his appointment as Health Officer comes from his time serving as a volunteer surgeon during the Civil War.

While his service is remarkable by itself, he requested and was given the opportunity to set up at Savage's Station, not far from the lines, so he could establish an aid station that would better serve the sick and wounded. He remained there, even after the Union's Army of the Potomac retreated and left him behind Confederate lines. Even though he was in enemy territory, he continued to treat those in his charge.

Swinburne was able to gain the cooperation of Stonewall Jackson and treated Confederate and Union soldiers alike. He advocated for those in his care, making the claim that these people no longer qualified as "belligerents" who should be kept prisoner. Instead, he claimed they were people in need of medical care, and that mattered more than their military status or allegiance.

After his tenure as Health Officer for the Quarantine in New York, Swinburne traveled to Europe. He arrived in Paris, France, just prior to the beginning of the Siege of Paris (1870). While you might be tempted to say that this was bad timing, it turns out that his presence was good timing for many who suffered illness and injury during the siege. His U.S. Ambulance Corps provided much needed care for those in need over a period of six months. For his efforts, Swinburne was decorated as Chevalier in the Legion of Honor for the French Third Republic. He was also recognized for his work by the Red Cross of Geneva.

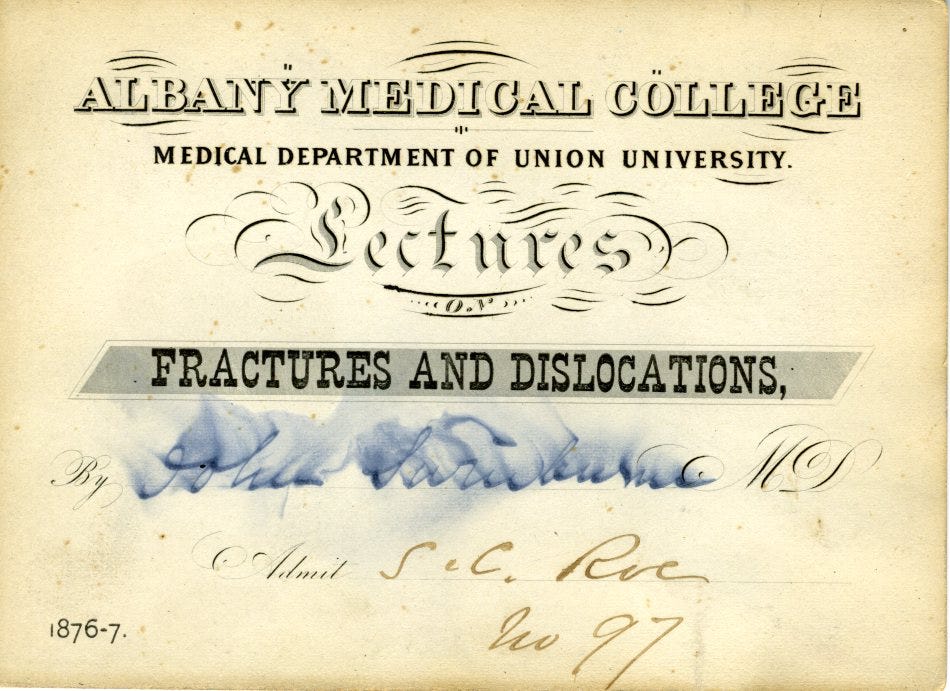

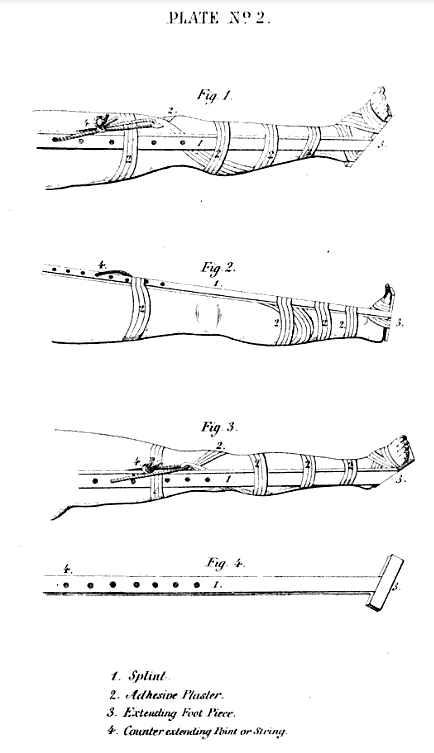

Swinburne also produced a medical writing titled Treatment of Fractures of Long Bones, by Extension in 1861 and also wrote another on treating gunshot wounds and preparing the patient for transportation. And not only was he a competent and innovative doctor, it was said in various reports that Swinburne treated his patients with great care and had a manner that often calmed them regardless of their injury or illness.

Swinburne served as mayor for the city of Albany and was a victim of election fraud and defamation, which led to the resignation of his opponent when it became clear legal processes would find them responsible. He also served as a member of Congress for one term, starting in 1885, but lost re-election in another controversial election (only 81 votes separated the two candidates).

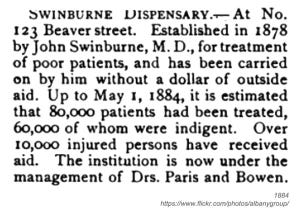

Whether you believe Dr. John Swinburne was as good as the author of his biography likes to claim, it is clear that he had many good points. It would be folly, of course, to believe he was a perfect person. It is clear that he enjoyed a certain amount of privilege and apparently did not have to worry about finances. However, I will leave you with this last bit of information.

Sometimes we need to take the time to celebrate the truly good things a person has done, whether they live today, or they come from our past. Here's to you, Dr. John Swinburne!

Thank you again for joining me for this week's Postal History Sunday. Have a great remainder of your day and a fine week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

As always, well done. A great job. You've inspired me to add details to some of my covers!