The day of the week was often a small matter of confusion to me when I was working on the farm full-time. The weather, soil conditions, and the farm task priority list had much more to say about what was going on most days. Sure, I did have to know which days had farm deliveries. But, there wasn’t really that much difference at the farm between a weekday or a weekend. They all had chores and farm-related activity.

Now that I only work on the farm part-time, I still have chores every day. But my other employment only allows me to be clueless about which day it is on the weekends. Hence I find myself talking about Saturday on a Sunday. Except, I am actually writing this on a Saturday so you can read it on a Sunday.

And now I sense that you’ve heard enough from this introduction. Whichever day of the week it is, it is clearly time for Postal History Sunday!

When Saturday was an important mail day

As I often do, I am going to transport us all back to the 1860s. A time before telephones and airplanes. The trans-Atlantic cable, which would enable the transmission of messages in minutes, had been laid between Ireland and Newfoundland in 1866 (the first cable in 1858 only worked for a few weeks). But, the cost for messages sent via that cable was ten dollars a word, with a minimum of ten words.

This left most people (and businesses) of the time with a single option for communications across the Atlantic Ocean. Their letters would be carried under the auspices of the postal services of the time and on steamships that typically took a week and a half to “cross the pond.” To put this in perspective, a question asked in a letter on the first of the month most likely would not receive a reply until the 21st at the earliest.

A person could actually make matters worse for themselves if they failed to pay attention to the days and times when ships that carried the mail were leaving port. Mail ships were not scheduled to leave daily (though the number of departures throughout the week would increase in the late 1860s into the 1870s). Through most of the 1860s, Saturday was a big day if you wanted to get your letter on its way. Otherwise, you would have to wait until midweek for the next sailing.

This explains the newspaper clipping shown above from the New York Herald on April 5, 1867. This short advertisement indicates the mail closing times in New York City for the European mails. One ship, the Atlantic, would be carrying mail for England and the Continent (Europe). A second ship, the City of Paris, carried mail for Ireland and the steamship Europe carried mail for France.

If you lived in New York City, this notice gave postal patrons a schedule by which they could assure that their letters would leave the ships before they departed. If you lived outside of the city, you would have to be certain to get your letter mailed early enough so that it could get to the foreign mail exchange office in New York before the ship’s departure.

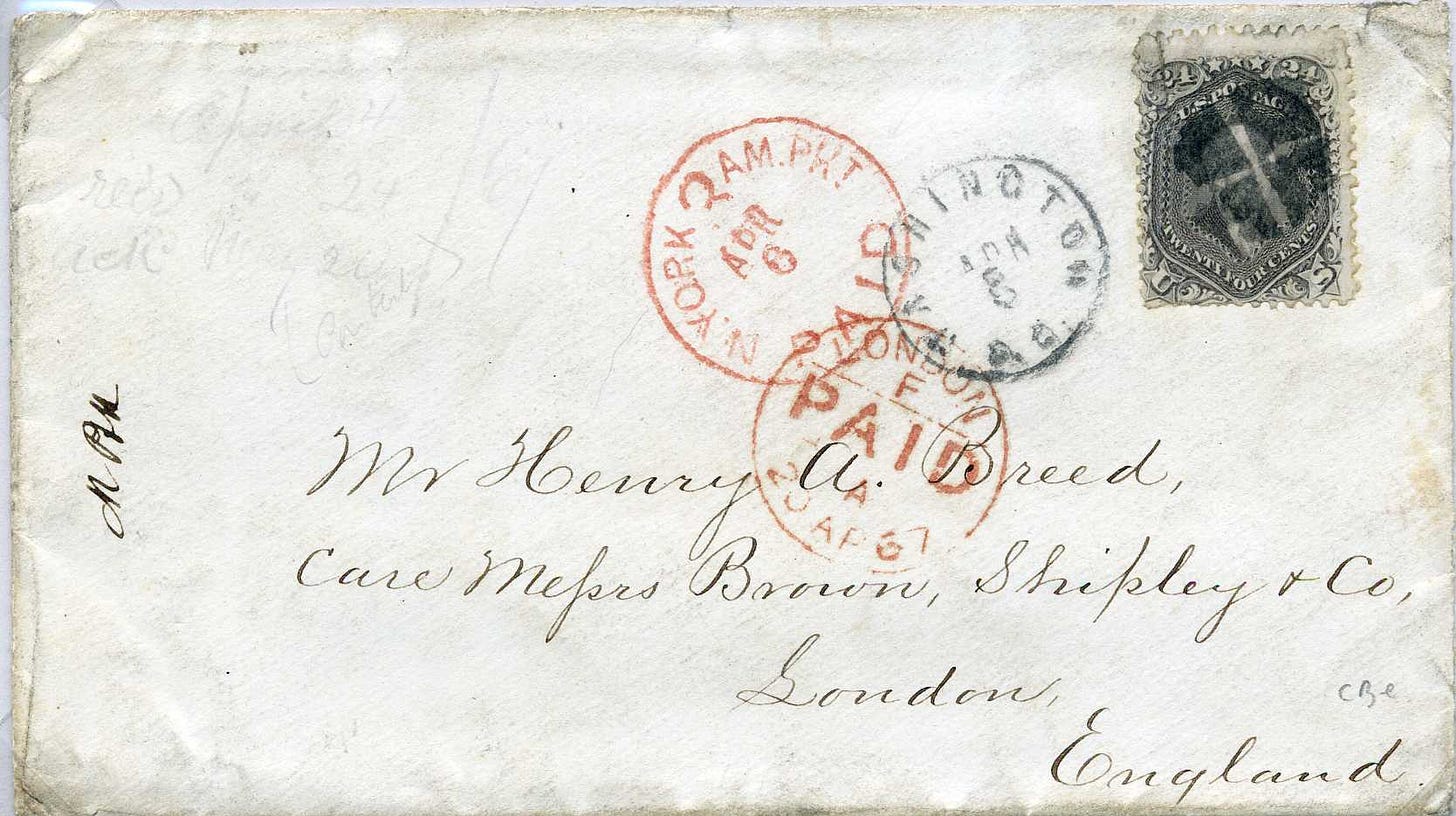

Shown above is a letter that was mailed in Washington, DC on Friday, April 5, 1867. Apparently, this was sufficient for the letter to get to the New York Foreign Mail office in time for the sailing of the Atlantic on Saturday the 6th. This is not terribly surprising considering there were excellent train services between the larger cities on the Eastern Coast of the US at that time.

The red New York PAID marking confirms for us that the letter was intended for the Atlantic. The date of the exchange mark was typically intended to be the scheduled ship departure date. And, since we know that letters to England were sorted to go on that ship, the case only gets stronger. When I checked sailing tables assembled by Hubbard and Winter, I also found that the Atlantic’s arrival in London matches the exchange marking date (April 20).

This letter took two weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean, which is quite a bit slower than most mail packets (ships) at the time. But it only cost 24 cents to send a letter that weighed no more than one half ounce. You could send much more than 10 words for much less than $100 if you used the postal services. Sometimes frugality wins over expediency.

If you look carefully at the top left of this envelope you might notice some penciled docketing that has been partially erased at some point in time (prior to my status as caretaker for this item). This docket tells us that the recipient actually had the letter in his possession on the April 24, four days after the letter arrived in London. This, of course, begs the question… “Why? Why four days later?”

The answer is actually in the address. The letter is mailed to Henry A. Breed, care of Brown, Shipley and Company. This company was known to provide financial services for US citizens abroad. In addition to those financial services they held or forwarded mail for their customers. Since this letter was not received by Breed until the 24th, we can conclude that they were either not concerned enough to pick up their mail on a daily basis or they were away from London at the time it arrived.

This letter apparently did not have anything of great importance since Breed records that they did not respond until May 20th. The author of the original letter had to wait for almost two months to get any answers to the questions they might have posed.

A dedicated letter writer

Henry Atwood Breed ( 1842-1914) served as a 2nd Lieutenant in Company F, the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry (Part of the Army of Potomac) until he was released for health reasons in October of 1863. This places him in major battles at Fredricksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. He apparently survived that action only to succumb to one (or many) of the illnesses encountered by soldiers.

Breed left behind an extensive correspondence (letters he received) that has been dispersed over time and some of those old pieces of postal history still retain the contents. One letter is available at the Spared and Shared site from his younger brother. This letter references preparations for a possible attack on the city of Pittsburgh. A second letter, available on the Civil War Pittsburgh website, is from the pastor of his church. It seems that Henry made mention of his exposure to so much death and injury and that, perhaps, it was dulling his sensitivity to it. And a third, written by a friend who was now serving as an officer for a colored regiment, can be found at the Spared and Shared website here.

According the Breed’s obituary in the Pittsburgh Daily Post, he traveled for a while after the war, which confirms how today’s cover fits his personal history. He would marry in 1868 and was working for the Culmer Spring Company in Allegheny in the 1870s.

Not the typical steamship company for trans-Atlantic mail

According the Reports of the Postmaster General for the period that spans the year 1867, 99% of letter mail destined for the British Mails was carried by the Cunard, Allan, North German Lloyd, Inman, Havre, and HAPAG steamship lines. For those of you keeping score, that list does not include the New York and Bremen Steamship Company.

This simple observation illustrates for us that this particular cover is quite unusual from a the perspective of a postal historian. This was only one of two times during the history of the New York and Bremen Steamship Company that they carried US mail to England. And this is the only example of a letter to the British mails carried by this steamship line that I have ever observed.

One of the reasons for low usage was this shipping line’s schedule. If you look at the advertisement, you can see that they only had one sailing scheduled per month. In contrast, the Cunard Line had maintained a weekly schedule for well over a decade and the Inman Line touted departures on Saturday and during the week for much of 1867. It was going to be very difficult for the New York and Bremen to capture the business of carrying mail if it couldn’t sail frequently.

Another reason for concern was the relatively slow speed of the Atlantic crossing when compared with other mail packets. This trip took two weeks at a time when shipping lines were routinely making the trip in nine or ten days. In short, the New York and Bremen Steamship Company was not the best option available to carry the mail.

To understand why, it is important to recognize that most of the other steamship lines were owned by companies that were headquartered in countries other than the United States. NGL and HAPAG were German, Inman and Cunard were British, and Allan was Canadian.

US steamship companies were at a disadvantage because their ocean going vessels had been commandeered for use during the Civil War. Once the war was over, there were several attempts to start new steamship companies to compete with the trans-Atlantic trade, but the competition was already quite stiff. The Havre Line was an exception in that it had resumed service after the Civil War was concluded in 1865. But it carried less than 5% of the mail to the British and it ceased operations at the end of 1867.

An older ship trying to keep up with newer technology

The Atlantic was an older ship (built in 1849) that had a wooden hull and was a side-wheel paddle steamer. In 1867, steamship technology had moved to screw propulsion and towards iron hulls. Originally built for the US-based Collins Line, it served with her sister ship, the Pacific, and two additional steamers, the Baltic and the Arctic until the Collins Line went bankrupt in 1858.

When the Atlantic was first constructed, the accommodations were considered to be excellent for the time. Once we get to 1858, this ship was beginning to fall behind the curve. The ship was sold and refitted to carry more passengers on the route from New York to Panama, catering to those hoping to go to California. But, this was short lived as the Atlantic was commandeered for the American Civil War.

Once the war reached its completion, the Atlantic returned to the New York - Panama route until it was sold to a new company, the North American Lloyd. This line intended to take advantage of the immigrant trade and purchased older, slower steamships. The business plan was to cram more people onto each ship at less expensive rates. And, while the ships were often full, the financial results were not sufficient.

New owners formed the New York and Bremen Steamship Company in 1867 and they sought to use a similar approach. As it was for the North American Lloyd, the mail contract was not seen as the primary driver for profit. The main reason the US Post Office offered a contract was the desire to employ US-based steamship companies if at all possible for mail carriage. It certainly did not have anything to do with a track record of success.

The Atlantic’s first trip for the new company did not go well. The ship was delayed on its first departure when it ran aground. It was successfully refloated and went on its way. But, on the return trip, severe weather washed everything on deck overboard and slowed the journey significantly. Our featured letter would have taken the next eastward crossing after that difficult journey.

The Atlantic would not make many more successful voyages after today’s cover was delivered. It was damaged in its last trip in late November of 1867. But this would not matter much to the New York and Bremen Steamship Company as they also ceased operations just after the end of the year.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Have you thought about combining these into a book??