Smoke and Mirrors

Postal History Sunday #206

Welcome to my weekly online article (or blog post or whatever other name you want to give it) where I share a hobby I enjoy with you. In the process of doing so, I do my best to make what I write accessible - and maybe even enjoyable - to all audiences, regardless of their knowledge of postal history. Put on the comfy slippers and pet Fluffy the cat or Spot the dog as you walk by. Grab a favorite beverage and a snack, but keep them away from the paper collectibles (and your keyboard)!

Are we all comfortable now?

I hope so, because it is time for Postal History Sunday!

I’m going to start by teasing you with this 1855 letter that was mailed from Firenze (Florence) in Tuscany to Bologna in the Papal States. It is properly prepaid as is indicated by the PD marking at the bottom right. But there is something more going on here that you can notice if you know what to look for!

So, let me give you a hint by telling you about something that occurred 146 years later in the United States.

Anthrax Poisonings Lead to Irradiated Mail

Some of you may recall the anthrax poisonings in 2001 that were a result of letters mailed via the US Postal Service (USPS). For those who might not recall this situation, anonymous letters were mailed that contained anthrax spores in the weeks after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Members of the media and Congress were the primary targets. Five people died and another 17 were infected, some of whom were postal workers and government mail room staff. Infected individuals included a 7-month old and a 94 year-old.

One of the responses at the time was for the postal service to begin irradiation of the mail in an effort to kill the anthrax spores. That irradiation process often changed the paper envelopes and contents, darkening it and making it more brittle. Plastics were typically impacted significantly, with warping and discoloration.

According to the EPA

The ionizing radiation used in the mail irradiation process can cause chemical changes in paper. Additionally, the mail is exposed to extreme heat during the process. The mail might come out brittle and discolored, looking and smelling like it has been baked in an oven. Books or documents with glue in their spines may have loose pages. Irradiation also might turn plastics brown, and warp CD cases or other plastic storage containers, and even affect credit cards. Even though it causes physical changes, irradiating mail does not make the mail radioactive.

Perhaps I recall this more than many others because stamp and postal history collectors were very concerned about mailing items via the USPS at that time - most opting to use other courier services. Why? Well, we collect paper items that we don't want damaged and we usually ship them in mylar (plastic) sleeves that would further damage the paper items we collect. I suspect those who received discolored mail that contained bills or advertisements for things they didn’t want were much less concerned about the situation.

Currently, the US Postal Service still irradiates mail destined to certain governmental addresses. So it is still quite possible for new pieces of irradiated postal history artifacts to be created in the present day.

The reason I bring this up is because irradiation was (and is) an effective way to sanitize the mail to prevent further anthrax poisonings. Ionized radiation can kill dangerous molds, bacteria and other pests. The first letter I showed you at the beginning of this article was also “sanitized” or disinfected with the technology of the time (not irradiation, of course). Unfortunately the disinfection attempts in the 1850s were not an effective solution for the cholera outbreak that prompted this treatment of the mail at the time.

Attempting to Kill Disease in the Mail - 1800s Style

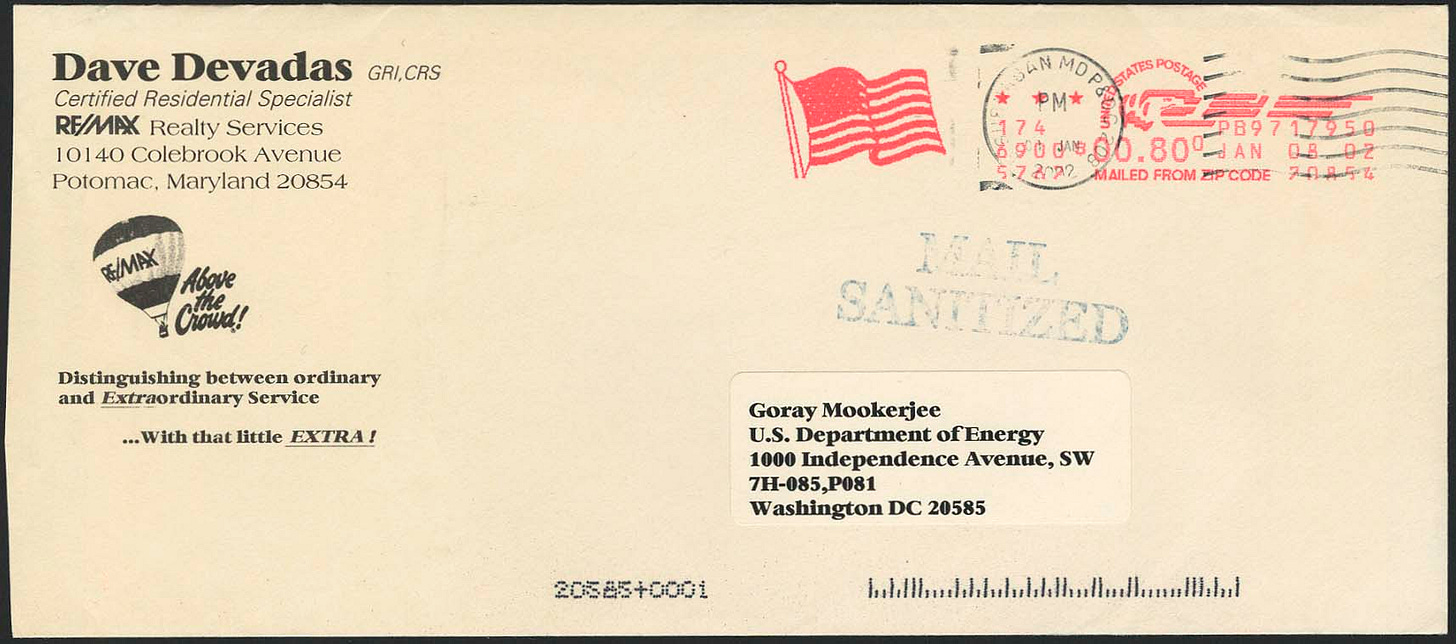

The envelope shown above was mailed from the United States to Rome in 1866, during the Fourth Cholera Pandemic (1863-75).

Take a moment and find the piece of white, modern paper with an arrow and you will see a single slit cut into the envelope. This was done to open up the letter so that the contents could be exposed to a disinfectant of some kind.

Initially mailed to Rome, this item was forwarded to Genzano (SE of Rome) where 15 centesimi were due for the forwarding service - see the red 15? It is likely that the fumigation occurred at Genzano since there are no records indicating that Rome, itself, was disinfecting mail at this time.

A fairly common practice in the first half of the 1800s was something postal historians refer to as the disinfection of mail. Incoming letters that may have traveled from or through areas that were identified as "unhealthy" or were in mailbags on a ship that was identified as carrying a disease were often (but not always) put through a disinfection process in an effort to prevent the mail from carrying that disease any further.

Each piece of mail was punctured, slit or cut in some fashion to allow either a fumigant or a vinegar mixture to access the interior of the item. Where larger volumes of mail were involved, tools were developed to aid in opening mail wrappers up prior to disinfection.

The paddle shown above (collection of the Smithsonian Postal Museum) was used in the United States to open up mail for fumigation with burning sulfur. I am sure it was not enjoyable to receive a letter punched full of holes and smelling of sulfur, but that was the price people paid for the sense that something was being done to control the spread of a frightening and dangerous disease.

Some of the first examples of disinfected mail can be traced back to the 1400s when the Republics of Venice and Ragusa "perfumed" the mail from the Levant (we would now call it the Middle East) with sweet smelling herbs and flowers. But, by the time we reach the 1850s and 1860s the practice of mail disinfection was in decline, but not unheard of.

Disinfection was often a process that was undertaken in an effort to show the public that the authorities were doing what they could in the face of an epidemic. It did not necessarily matter that the actual process was effective or not. By the 1860s, the actual causes of the spread of cholera were known - and it was clear that disinfecting the mail was merely a performance and did little to safeguard the public.

More About the 1800s Cholera Outbreaks

As trade and travel increased between Europe and India, the opportunity for the spread of cholera increased. What people did not fully understand until 1885 was that cholera spread occurred when a person ingested something that was contaminated with the feces of an infected organism. Contaminated water was, in fact, identified as the likely culprit in 1855 by a British physician (John Snow). But, as is often the case with humantiy, the debate raged on for a time after that before it became accepted fact.

It turns out, the best solution would have been to secure clean water sources, provide sanitation services, and develop and maintain basic food safety procedures. And, in fact, improvements in clean water and sanitary systems in subsequent years would help much of Europe to better handle later pandemics as the century progressed.

And, as was/is often the case, good preliminary solutions during an outbreak are quarantines and travel restrictions. But, that is rarely popular - especially when it was bad for business. We can all attest to the truth of this when we consider fairly recent reactions to the Covid pandemic. So, some locations returned to the disinfection of mail during the Third and Fourth Cholera Pandemics to show that something (even though it did not work) was being done.

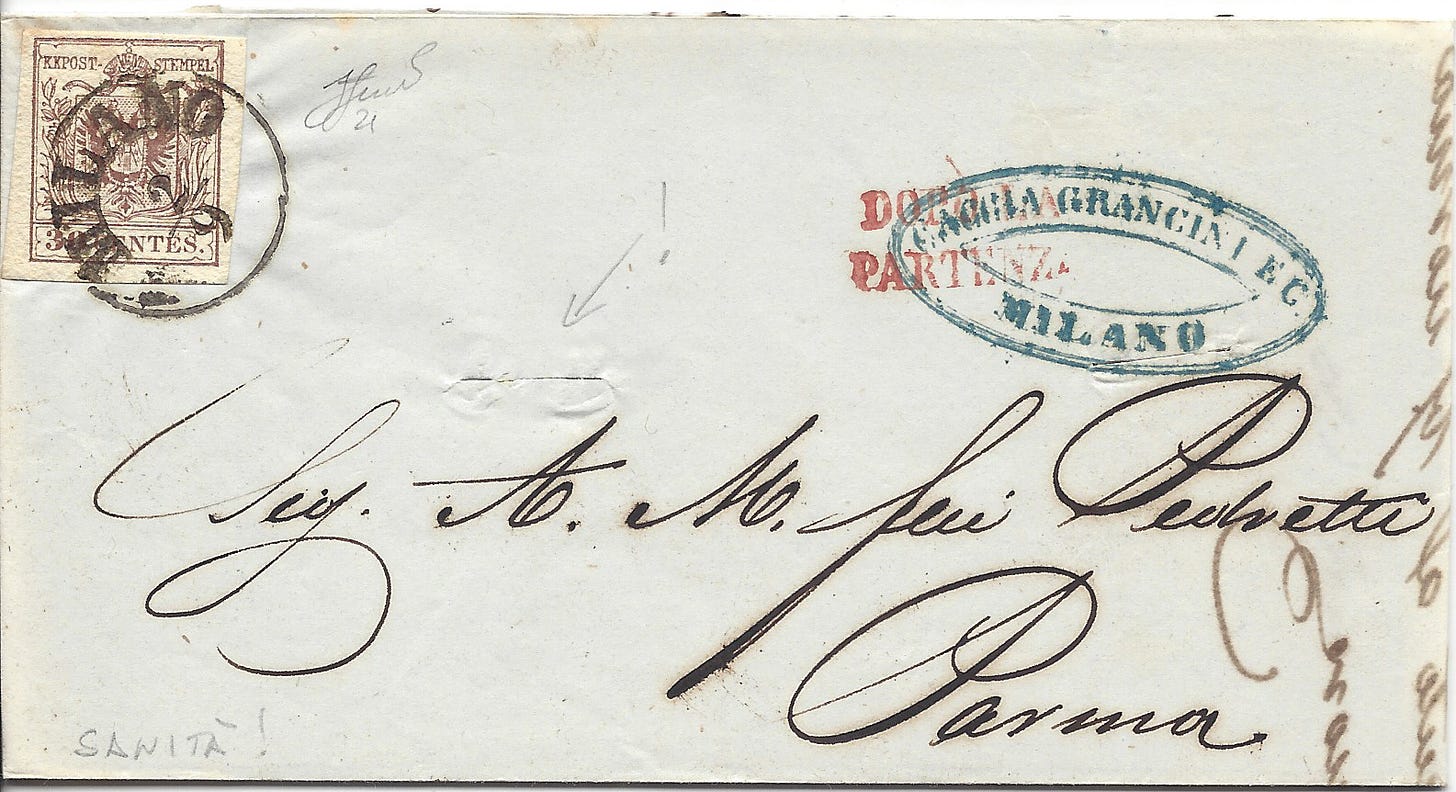

The item above was mailed in September of 1855 from Milan to Parma (Italy). The Third Cholera Pandemic (1852-1860) was just coming off its peak and the nearby city of Ferrara (east of Parma) still provides data for scientists to analyze today. Clearly, the spread of cholera was on the minds of the people in this region - and for good reason.

If you look carefully, you can find two disinfection slits that look very much like a person pushed a blade into the letter to allow the fumigant to access the contents. You can look for the penciled in exclamation point to help locate one of the two slitted areas. Because there is no staining, it is unlikely a liquid solution was used on this item. I presume it was fumigated instead.

The folded letter shown above initially got my attention because of the red marking that reads Dopo la partenza, which means "after departure." It actually made its way into a an earlier Postal History Sunday that showed multiple examples of items that arrived too late to take the train or ship or coach that carried the mail away from the post office.

The disinfection slits were just icing on the cake for me! It's always good to have more than one point of interest.

That brings us back to our introductory cover.

This letter was mailed during a time when the Austrians and certain Italian States had a postal agreement that provided uniform postal rates between the participants. The postage rate was dependent the weight of the letter and the distance it had to travel. The letter shown above traveled over 10 Austrian meilen (75 km) and no more than 20 meilen (150 km). The required postage for a simple letter (it did not weigh more than 15 denari) was 4 crazie, the monetary unit for Tuscany at the time.

There are two slits in this envelope, see if you can locate them both without my help. If you need to see a bigger version of the image, you can click on it to do so. There is also a long rectangular marking that is not very easy to read. However, if it were perfectly struck it would say disinfettata or some variation of that word. If someone has expertise in this area and can help further with this marking, it would be appreciated.

And now you know a little better why I enjoy postal history. It opens up a window... or a door... to the story that surrounds each item. Sometimes the story it tells leads to events of global consequence - such as the Cholera Pandemics. Other times, they just tell a personal story for a person who lived a life just like ours, but in a different time.

I wonder what stories we'll explore next week?

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I remember the Anthrax scare, but I didn't realize that the USPS was still irradiating some mail. I also learned about how far back disinfecting the mail went. Always fascinating and good history lessons. Thanks, Rob.

Excellent and interesting article Rob!