Welcome to Postal History Sunday! If you've been here before, you know what to do. If you haven't - we're glad you decided to visit.

Grab a favorite beverage, making sure to keep it away from the keyboard or the paper objects I will be sharing today. Settle into a comfy chair and kick off the tight shoes and put on the fuzzy slippers. If your brain is occupied by things that are less than positive, put them aside for a time while I share something I enjoy.

And maybe...just maybe. We'll all learn something new!

Clues to help us “read” a cover

One of the skills a postal historian develops over time is the ability to "read" each cover. The process of reading a cover allows a person to discover details about where an item was mailed, where it was destined to go, and the places it visited on the way there. Reading a cover also helps us to determine what the required postage was and how much of that postage was actually paid.

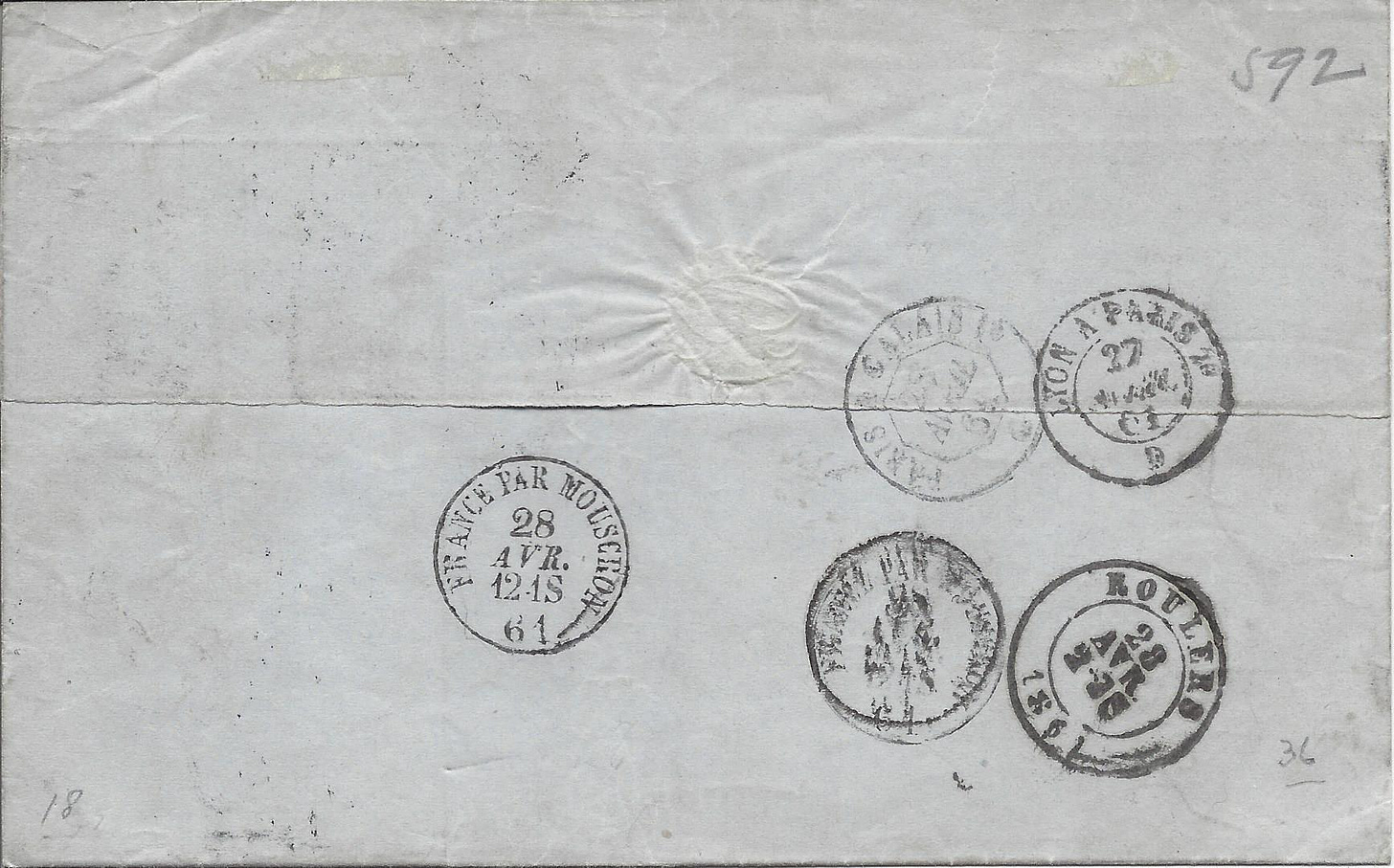

Sometimes, there are sneaky clues that can either help us read a cover or confirm for us that our reading is correct. In order to illustrate my point, I thought I'd start today with this heavier letter sent from France to Belgium in 1861.

This letter entered the French mail system at St Etienne, France on April 27, 1861 and was destined for Roulers, Belgium. The route this particular letter is not a big secret, because there are numerous transit postmarks on the back of the folded letter. The letter boarded a train at Lyon that was bound for Paris on the same day it was mailed, but it didn't leave on the train out of Paris until the next morning.

It left Paris on a train bound for Calais but, instead of going all the way to Calais, it took a turn off that track and headed for Belgium. This is confirmed by two strikes of the marking that reads "France par Mouscron." It finally arrived at Roulers on the 28th on the train arriving there between 2 and 3 in the afternoon.

I suspect most people could figure out that markings dated on the 27th would have been placed on the envelope before those dated April 28. But, you might be wondering how I deciphered the ordering of these markings with such certainty. And, you might also be justified in asking how I could make a claim that the letter arrived in Roulers between 2 and 3 in the afternoon.

The sneaky clue that provided the answer for that last part was located in the receiving postmark for Roulers (Rouselare). Belgian rail markings often included a time stamp which allowed them to track the train that carried the letter. The letter "m" would stand for "matin" (morning) and "s" indicated "soir" (evening). Or, if it makes the US readers feel better, AM and PM.

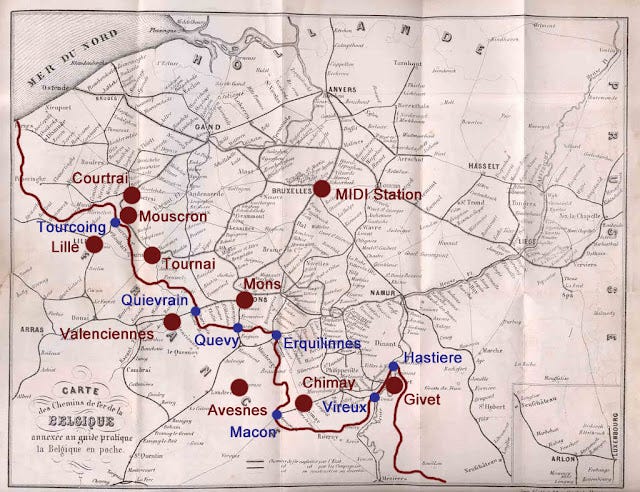

We can actually see a better (and clearer) example of the time marking here:

This is the Belgian exchange marking that was applied on the Belgian mail car that ran from Lille, France to Mouscron, Belgium. It was there between noon and 1PM according to the 12-1S portion of the transit marking.

The actual border crossing this letter took from France to Belgium was at Tourcoing (France). For those who like a little bit of trivia, the rail line from Tourcoing to Mouscron was the first ever constructed to cross a European border (1842). At that time, Belgium was committed to developing a strong rail system, partly in hopes of capturing the transit of people, mail and goods between nations. The French, on the other hand, were slower to… ahem… board the train. But they were also unwilling to accept that Belgium might align more with the Germans if France failed to develop modern transportation connections with Belgium.

Mouscron was a key junction for the Belgian railroads at the time this letter was mailed. Since this letter was destined for Roulers (northwest of Coutrai), it would have been transferred to the northbound train at Mouscron.

There are other sneaky clues that help us with the ordering of these postmarks. For example, French railway postmarks typically give us the direction of the train by the ordering of the town names. Lyon-Paris would indicate that the train was traveling in the direction from Lyon towards Paris. Similarly, the Paris-Calais marking tells us it traveled on a train traveling away from Paris and toward Calais. We just need to understand that it was not required that the letter travel the whole length of that track from origin to terminis.

Another , not so sneaky, clue to determine the order these markings were applied has to do with geographical knowledge - or access to period maps. If you know St Etienne is relatively close to Lyon, it then makes sense to start with the Lyon-Paris marking.

The other puzzle with this cover is determining how much postage was paid (and why that much postage was paid). The three postage stamps each represent 40 centimes in postage paid. The "P.D." marking tells us it was considered paid in full.

Thankfully, I am do have access to resources that provide me with some of the postage rates during that time. A letter from France to Belgium cost 40 centimes per 10 grams in weight (April 1, 1858 - December 31, 1865). So, this must be a triple weight letter.

A simple letter would weigh no more than 10 grams and required 40 centimes in postage.

A double weight letter would weigh more than 10 grams and no more than 20 grams and would cost 80 centimes.

A triple weight letter would weigh more than 20 grams and no more than 30 grams. Its cost was 120 centimes (or 1 franc 20 centimes).

But, believe it or not, I can actually tell you that this letter weighed 25 grams. It’s not because I have all of the original contents and I put it on a scale. It’s because of this sneaky clue:

Clues to figure out why it cost what it did to mail

I thought I would stick with Belgian postal history and show a folded letter from Mettet, Belgium next. Mailed on December 16, 1854 to Charleroy, this is an internal (or domestic) letter, rather than a letter exchanged between nations.

This is a domestic letter with two 20 centime stamps to pay the postage (a total of 40 centimes). The question is - why was 40 centimes needed to mail this letter?

Belgium's internal rate structure from July 1, 1849 to October 31, 1868 was fairly complex. It maintained both a distance component and a weight component to determine the cost of postage for any given item. For example, any letter that had to travel 30 km or more would have to follow one rate table and local letters (less than 30km distance) would follow another.

The weight component was not a linear progression either. The base rate for a simple letter was for mail weighing no more than 10 grams. That would have covered the majority of letter mail, so that seems simple enough. The next rate level was for mail that weighed over 10 grams and no more than 20 grams. The third rate level was for mail that weighed more than 20 grams and no more than 60 grams.

So, what are the clues that we can use to figure out the rate for the folded letter shown above?

Clue #1: 40 centimes in postage paid appears to have covered the cost

The stamps have their cancellation markings and there are no markings on the cover that tell us more money is owed by the recipient. That means the required postage was probably 40 centimes OR less. After all, a postal service only cares if you don't pay enough. If you want to pay too much, that's your business.

No, really. Try it. Put more postage than you need to on a letter and see what happens.

Clue #2: How far apart are Mettet and Charleroy?

It turns out that they are roughly 24 km distant from each other. This tells us that this was probably a "local" letter. I say "probably" because the distances we see in today's maps are not necessarily representative of how the Belgian postal services in 1854 classified it. Instead of having exact mileage, most distance rates were calculated by seeing where each possible destination settlement landed in a table predetermined by the post office. Still, given the modern measurement, odds are very good that this was a local letter (under 30km).

So, if we know that a local letter required 40 centimes for an item weighing more than 20 grams and no more than 60 grams (Jul 1, 1849 - Oct 31, 1868), we have (mostly) solved the problem! We cannot eliminate the possibility that this was an overpayment for either the first or second rate levels. But, the simplest solution is to say that the postage paid the third rate level for a local letter.

Clue #3 A weight is referenced in a docket:

Located at the top center of this piece of mail is a scrawl that actually reads "25 Gms." It is likely a weight written by the postal clerk. And, as it turns out, 25 grams is between 20 and 60 grams. (You can believe me, I have a degree in mathematics.) So, this letter was mailed at the third rate level for a local letter, which required 40 centimes in postage.

I could have come to the correct conclusion with either the distance or the weight docket, but there are times when one clue is not enough. And, even if one IS enough, it can be helpful to have corroboration between clues - which is what we have here. If they happen to contradict each other, we would have a bit more of a puzzle on our hands - and it could have been one that was not solvable.

Let’s try it again to get a repetition in!

As both a life-long learner and an educator, I am a big believer in getting repetitions in for better retention. So, let’s look at another letter from Belgium!

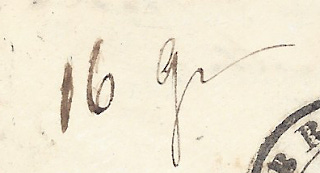

This cover originated in Bruges, Belgium and was sent to Dublin, Ireland in 1858. The two postage stamps total 80 centimes in postage paid to mail this letter.

The postage rate between these two locations was simpler than the internal Belgian rates. There was no distance component and the weight component was linear - 40 centimes per 15 grams (effective Oct 1, 1857 - July 31, 1865). So, the easiest (and correct) conclusion is that this paid the postage for a double weight letter (something over 15 grams and up to 30 grams).

You probably figured out where I was going with this one - and that’s a good thing. This letter and its contents weighed 16 grams according to the docket found just above and to the left of the Bruges postmark. In other words, this item was just BARELY over the maximum for a simple letter. Still, it didn’t matter if you were one gram or 14 grams over, it was still going to cost you another rate of postage.

Unlike the second example, this one is much easier to read and identify. In fact, it was this cover that taught me to look just in case a letter weight clue is a part of a postal history item. Most mail does not bear a docket or marking that indicates the weight of the letter. But, when it does, it provides us with extremely valuable information.

Eights are wild

I thought this folded lettersheet mailed in 1853 from Switzerland (Chaux-de-fonds) to Paris (France) would be a logical next step for our sneaky clue progression. See if you can figure this one out without me giving you the answer.

This was an unpaid letter (no postage stamps), so the recipient would be expected to pay the full required postage in order to receive the letter. The postage rate at the time for mail fom Switzerland to France was 40 centimes per 7.5 grams in weight.

There are actually three numerical markings on this particular item. You probably recognize the two "8's" - but the squiggle at the lower right (looks like a lower case "n") is actually a "4."

The "4" has been crossed off (notice the two lines going through it) because the receiving postmaster must have determined that the letter weighed too much. They put the larger "8" in the middle indicating that the recipient must pay 8 decimes (80 centimes) to receive the letter. The French preferred to do their accounting in decimes (1 decime = 10 centimes) and you can think of a decime as a dime, if that helps you.

Initially, I did not understand the purpose of the 2nd "8" at the top left. Maybe the postmaster just wanted everyone to understand "Hey! I really meant 8 decimes, not 4 decimes. See! I put it here twice!" But, even more likely is that the smaller "8" is the weight of the letter - 8 grams. They just did not bother putting the weight unit with it this time.

By putting the weight on the letter, I suspect they felt it would serve as an explanation as to why they rejected the first 4 decimes rating. The recipient, on the other hand, probably did not need or want to know that the weight was over by just a half gram. If anything, they were probably just annoyed that they had to pay twice as much as they might have anticipated for this particular letter.

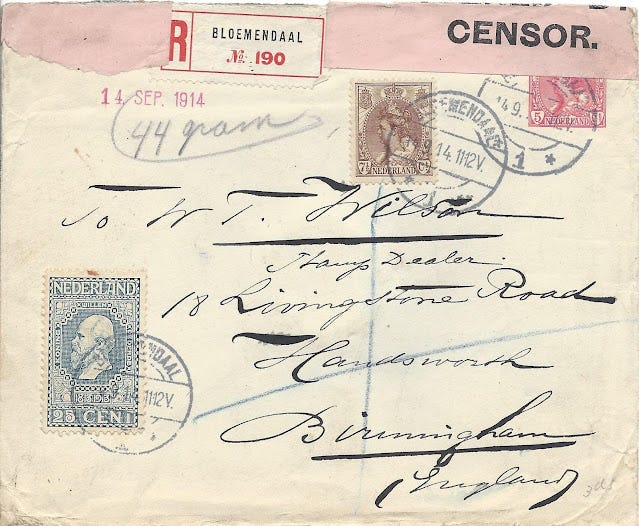

Not just an 1850s thing

Below is a letter mailed from the Netherlands to England in 1914. World War I was actively engaged at the time, so most mail between nations had to go through a censorship process. After the censor read the letter and removed any information they didn't feel should be included, they would reseal the letter with some sort of seal or tape (like the pink tape you see in the cover below).

This letter carries 37 1/2 Dutch cents in postage stamps. And, at the top left, you can see the weight "44 grams" written in pencil. I wonder why that is there?

Well, I'm going to work backwards to get to the answer this time. The fee to send registered mail from Holland to England was 10 cents (Jan 1881 - Mar 31, 1921). That leaves us with 27 1/2 cents in postage paid by the blue stamp at lower left.

The letter rate for mail from the Netherlands to England was as follows:

1st 20 grams: 12 ½ cents

each additional 20 grams: 7 ½ cts

If the letter weighed 44 grams, we would be in the third weight level, then the postage rate should have been 27 1/2 cents (12.5 + 7.5 + 7.5).

As a side note, take a look at the address panel on this envelope - "To W.T. Wilson Stamp Dealer"

Yes, this was a piece of mail to an individual who sold postage stamps to philatelists (people who collect and study postage stamps). That, by itself, could explain the interesting mix of stamps used to pay the postage on this item.

Giving credit where it's due

We’re going to stick with looking at numerical clues - because they’re so much fun! This time, we're going to look at a letter that was sent from Newport, Rhode Island to Paris, France in 1866. Can you guess what "sneaky clue" I am going to focus on?

I suppose, for those of you who are not familiar with postal history OR this period of mail, EVERYTHING might feel like a sneaky clue. I certainly understand that because I have a good enough memory to recall when it seemed as if each cover was more mystery than certainty.

So, this time around, let me show you how ALL of the pieces - sneaky or otherwise - work together.

The red "45" at the bottom left is equivalent to the amount of postage found on this envelope: one 24-cent stamp, two 10-cent stamps and one 1-cent stamp = 45 cents total.

The postage rate for letter mail from the United States to France at the time was 15 cents per 1/4 ounce of weight (effective April 1857-Dec 1869). Forty-five is a multiple of fifteen, so that's a good sign.

I took a moment to enhance the red pencil mark and remove some of the distracting marks from the address panel so you can better see them. The numbers in red pencil read "36 / 3" - which is exactly what they should be. But why?

The "3" is in reference to the fact that this letter must have weighed more than 1/2 ounce and no more than 3/4 ounce. In other words, postage needed to be three times the simple letter rate (15 cents). So, this number confirms the amount of postage AND the "45" marking at the lower left. So far so good.

But, what is it with the "36"?

This is where the docket AND the round, red Boston marking come in. The docket reads "per Cunard Steamer of Wed Dec 5th from Boston." The red Boston marking is dated December 5 and states that the postage is paid. It certainly is nice that both of these parts of the cover agree about when this letter was put on the Cunard Line's Africa - but this is ALSO where the "36" ties in to the whole story.

Of the 45 cents collected in postage by the United States, thirty-six cents were to be passed on to France so they could pay for their expenses AND so they could pass money to the British. After all, the Cunard Line was under contract with the British Postal Service to carry the mail across the Atlantic.

In the end, the postage was broken down as follows:

9 cents for the United States

36 cents went to the French who used it to pay for

18 cents to the British for the trip across the Atlantic

6 cents to cover the British surface mail and transit across the English Channel

12 cents kept by the French to pay for their own postal expenses.

Now, these amounts are rough approximations, because the British wanted their shillings and pence and the French their centimes, decimes and francs. So, of course, the French would take their equivalent from the US 36 cents and then pass amounts in their own currency on to the British.

In any event, the 36/3 marking is correct because the ship that carried the letter across the Atlantic had a contract with the British. If that ship had been contracted with the United States or France, the first number would have been different.

And that's how it all ties together. But, why is this interesting or important to a postal historian?

The simple answer is that many covers don’t have ALL of the clues that this one has. They often only have some of them. Which means we need to know what each clue means so we can effectively fill in the blanks.

For example, what would happen if we had a letter that did not have a docket, did not have the red "45" and the red Boston marking was smeared? In that case a "36/3" clearly written in pencil and 45 cents in postage on the envelope would still be good enough to put the story together because we've seen items (like this one) where all of the pieces are completely and clearly spelled out.

And sometimes it just wasn't enough

Here is an 1856 folded letter that was sent from Nancy, France to Paris. There is a 20 centime stamp at the top right and the red box at the top left reads "affranchissement insuffisant" (insufficient postage).

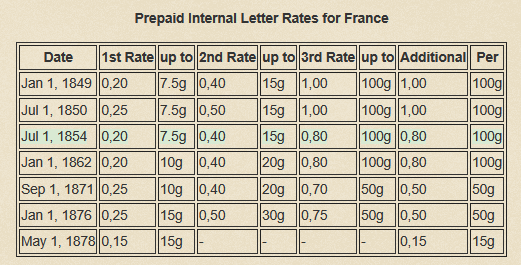

As a public service, I now give you a table that shows the internal letter rates for France during the second half of the 1800s. The third row illustrates the rates that apply for this item.

A simple letter would weigh no more than 7.5 grams and would cost 20 centimes. Apparently, the person who mailed this felt the letter was not too heavy and paid the cost for a simple letter. The French postal clerk, on the other hand, did not agree - and they gave us evidence of that fact.

Well, well. It looks the writer exceeded the weight limit by one-half gram (the marking above reads "8 g" or 8 grams). That’s the second time we’ve seen that in Postal History Sunday today. It’s almost enough to make a person wonder if some postal clerks took an inordinate amount of delight in catching slightly overweight letters!

For reference, 1/2 gram is the weight of half of a typical business card or half of a raisin. It's not much. But, rules IS rules - and this letter simply weighed too much. Which means the amount of postage paid should have been 40 centimes.

At that time, the regulations for short paid mail in France required the recipient to pay the full amount of postage AS IF nothing had been paid at all. In other words, the postage stamp paid for none of the postage required to send this item. Think of it as a donation to the French Post Office if that helps your understanding.

It may not seem fair that no credit was given for the postage provided - but at the time post offices around the world were trying to enforce pre-payment of letters. I suspect they were hoping a few harsh economic lessons would be enough to get the point across.

So, the amount due to the recipient was 40 centimes, which is represented by the big squiggle shown in the image at the left. Yes, that is a "4," which stands for 4 decimes (equal to 40 centimes). Remember, the French often used decimes for postal accounting, which is the equivalent to Americans referring to 4 dimes instead of 40 cents.

Now, if you are still staring at the squiggle and STILL don't see a "4," I understand. This just might be one of those times you're just going to have to trust me. And if you can’t bring yourself to do that, you can just shrug and move to the next section.

Let's get a bit more complicated!

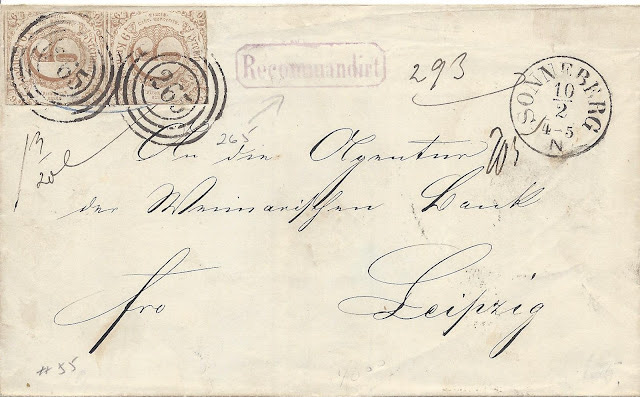

Take a look at this 1865 folded lettersheet mailed from Sonneberg (Thuringia) to Leipzig (in Saxony). Thuringia, like the Hessian States, that used the house of Thurn and Taxis for their mail.

The target-like cancellations on the stamps have the number "265" in the center, which was the number assigned to the Sonneberg post office. The pencil number "265" with an arrow pointing to the purplish marking was put on the cover by a previous collector. The intent is probably to indicate that they determined that the purple marking was also applied in Sonneberg.

This marking indicates that the letter was sent as a "registered" letter (Recommandirt). In order to register a letter, an additional 6 kreuzer in postage was required. And, some of the numbers found on this cover - those at the top right - are numbers used to track the progress of this letter as it traveled to its destination. The "293" was likely the number in the Sonneberg ledgers that tracked this letter's departure and "205" may well have been Leipzig's ledger number to record the reception of the letter at their office.

So - we have 6 kreuzer spoken for - that leaves us with 12 kreuzer in postage paid.

The rate between Sonneberg and Leipzig was 6 kreuzer per loth. At the time, mail in the German States included both a distance and a weight variable to determine the postage required. The distance between the two cities was between 10 and 20 meilen (German miles) - if they had been closer it would only cost 3 kreuzer per loth.

And, there it is! Our sneaky clue resided at the left, just under the postage stamps. This scrawl in black pen reads "1 3/20 L," with the "L" standing for loth, the weight unit in use by German postal services at the time. One loth is roughly equivalent to a half ounce.

So, this letter weighed over one loth and no more than 2 loth, which made it a double weight letter and the total postage needed can be calculated in this fashion:

Registration Fee 6 kreuzer

Rate per loth for distance between 10 & 20 meilen - 6 kreuzer x 2 = 12 kreuzer

Total = 18 kreuzer

Look on the other side

Here is another piece of French postal history to consider from 1864. This item was also sent as a "registered" item (Chargé). But, that's not what I want to focus on this time around.

This item was returned to the sender, which would have been the Tribunal Court in Chambery. The contents are a court summons that apparently did not find the person they were "summoning!"

But, how did I know this was returned to the sender?

The sneaky clue is at the bottom right, just under the Chambery postmark. The words "au dos," when placed on a piece of letter mail explains that the carrier or clerk should "look on the back" for more explanation. So, I looked on the back - and this is what I found:

The word "Inconnu," which would translate to "unknown," is written on the reverse of this cover. Apparently, the post office in Chambery was unable to locate the recipient of this court summons and they simply returned it to the Tribunal.

Well, if the postal service can't find you, I guess you don't need to go to court.

I wonder how that turned out?

And sometimes, there is no postal significance

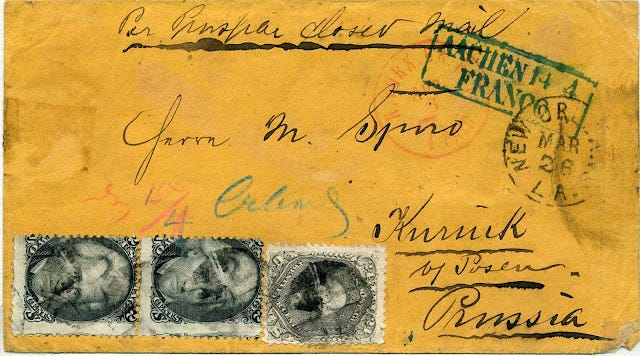

Let's close with this 1867 envelope that was sent from New Orleans, Louisiana to Kurnik, Prussia (now in Poland). The postage applied is 28 cents, which is the correct postage for a simple letter sent to Prussia (not weighing more than 1/2 ounce). The New Orleans, New York and Aachen markings clearly show the travels this letter took and the dates it visited each location. A single marking on the back tells us it arrived at the destination post office on April 15.

But, what is all of this? The use of blue and red pencil might be an indication that there might be some postal significance - but what?

I have to admit that I was puzzled by these markings for some time. The numbers "15" and "4" really don't connect to any postal rate calculations that I could determine. And, there was no reason (and no way) for this item to have traveled through Orleans, France.... unless that is not the word "Orleans" written in blue.

So, this particular set of markings sat in my "to be solved" list for a long time. Until, one day, I asked the right people and got an answer that makes perfect sense.

This is a docket written by the recipient, simply recording that the letter was received on the 15th of April (4th month) from Orleans (New Orleans). The little red squiggle before the numbers was simply an abbreviation to indicate a received date, which matches the date of the postal arrival date on the back. They must have changed from a red to a blue pencil because the former was dull and they just wanted to finish the job without pausing to sharpen it.

Sometimes the answer is so simple that it is almost embarrassing to admit it to others. In this case, I think I can hide behind the fact that most Americans list dates in month/day order rather than day/month order. That's about the only defense I have right now - but I do feel much better now that the mystery is not so much of a mystery any more.

Thank you for joining me for a longer Postal History Sunday this week. I hope you were at least slightly entertained and maybe you learned a new thing or two. Have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.