Sneaky Clues - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday! If you've been here before, you know what to do. If you haven't - we're glad you decided to visit.

Grab a favorite beverage, making sure to keep it away from the keyboard or the paper objects I will be sharing today. Settle into a comfy chair and kick off the tight shoes. If your brain is occupied by things that are less than positive, put them aside for a time while I share something I enjoy.

And maybe. Just maybe. We'll all learn something new!

-----------------------------

I find postal history to be enjoyable in part because I also happen to enjoy puzzles. The process of looking for the clues on an old piece of mail to figure out as much of the story that surrounds it is where I get much of my enjoyment from the hobby.

Like any type of puzzle, whether it is Crosswords, Sudoku, or some other puzzle of your choice, there are strategies that can be learned over time. As you are exposed to more puzzles, your experience grows, giving you a broader range of possibilities for seeking solutions. The same holds true for me as I explore postal history. Over time, I have learned to look for a broader range of clues that can help me solve each "puzzle."

Today, I thought I'd show a few sneaky clues that, once you see them, seem pretty easy. But, if you don't know to look for them, they are easy to overlook.

Weight, Weight - Don't Tell Me

Pardon me for using the play on words to reference the NPR news quiz. But, it got into my head and the only way to get rid of it was to actually use it. Now it is stuck in YOUR head and we can deal with the discomfort together!

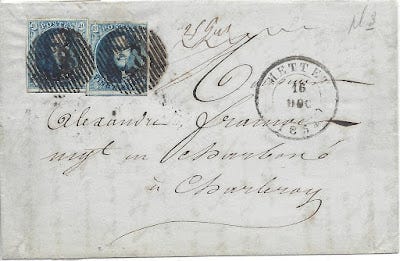

The first item I wanted to share with you today is a folded letter from Mettet, Belgium that was mailed in December of 1854 to Charleroy, also in Belgium.

So, this is a domestic letter that shows two 20 centime stamps that were used to pay the postage (a total of 40 centimes). The question is - why was 40 centimes needed to mail this letter?

Belgium's internal rate structure from July 1, 1849 to October 31, 1868 was fairly complex. It maintained both a distance component and a weight component to determine the cost of postage for any given item. Any letter that had to travel 30 km or more would have to follow one rate table and local letters (less than 30km distance) would follow another.

The weight component was not a linear progression either. The base rate was for mail weighing no more than 10 grams. That would cover the majority of letter mail. The next rate level was for mail that weighed over 10 grams and no more than 20 grams. The third rate level was for mail that weighed more than 20 grams and no more than 60 grams.

So, what are the clues that we can use to figure out the rate for the folded letter shown above?

Clue #1: 40 centimes in postage paid appears to have covered the cost

The stamps have their cancellation markings and there are no markings on the cover that tell us more money is owed by the recipient. That means the postage rate was 40 centimes OR less. After all, a postal service only cares if you don't pay enough. If you want to pay too much, that's your business.

Clue #2: How far apart are Mettet and Charleroy?

It turns out that they are roughly 24 km distant from each other. This tells us that this was a "local" letter. So, if we know that a local letter required 40 centimes for an item weighing more than 20 grams and no more than 60 grams, we have (mostly) solved the problem!

We cannot eliminate the possibility that this was an overpayment for either the first or second rate levels. But, the simplest solution is to say that the postage paid the third rate level for a local letter.

Clue #3 A weight is referenced in a docket:

Located at the top center of this piece of mail is a scrawl that actually reads "25 Gms." It is likely a weight written by the postal clerk. And, as it turns out, 25 grams is between 20 and 60 grams. So, this letter was mailed at the third rate level for a local letter, which required 40 centimes in postage.

I could have come to the likely correct conclusion with either the distance or the weight docket, but there are times when one clue is not enough. And, even if one IS enough, it can be helpful to have corroboration between clues. If they contradicted each other, we would have a bit more of a puzzle on our hands - and it could be one that is not solvable.

Here is another piece of letter mail from 1858. This cover originated in Bruges, Belgium and was sent to Dublin, Ireland. The two postage stamps total 80 centimes in postage paid to mail this letter.

The postage rate between these two locations was simple: 40 centimes per 15 grams (effective Oct 1, 1857 - July 31, 1865). So, the simple conclusion is that this paid the postage for a double weight letter (something over 15 grams and up to 30 grams).

Well, we can tell you that this letter and its contents weighed 16 grams according to the docket we can find just above and to the left of the Bruges postmark.

Unlike the first instance, this one is much easier to read and identify. In fact, it was this cover (and one other) that taught me to look just in case this clue is a part of a postal history item. Most mail does not bear a docket or marking that indicates the weight of the letter. But, when it does, it can provide valuable information.

Eights are Wild

I thought this folded lettersheet mailed in 1853 from Switzerland (Chaux-de-fonds) to Paris (France) would be a logical next step. See if you can figure this one out without me giving you the answer.

This was an unpaid letter (no postage stamps), so the recipient would be expected to pay that postage in order to receive the letter. And the rate was 40 centimes per 7.5 grams in weight.

There are actually three numerical markings on this particular item. You probably recognize the two "8's" - but the squiggle at the lower right (looks like a lower case "n") is actually a "4."

The "4" has been crossed off (notice the two lines going through it) because the receiving postmaster must have determined that the letter weighed too much. They put the larger "8" in the middle indicating that the recipient must pay 8 decimes (80 centimes) to receive the letter. In case you didn't remember, the French preferred to do their accounting in decimes (1 decime = 10 centimes) and you can think of a decime as a dime, if that helps you.

Initially, I did not understand the purpose of the 2nd "8" at the top left. Maybe the postmaster just wanted everyone to understand "Hey! I really meant 8 decimes, not 4 decimes. See! I put it here twice!" But, even more likely is that the smaller "8" is the weight of the letter - 8 grams. They just did not bother putting the weight unit with it this time.

By putting the weight on the letter, I suspect they felt it would serve as an explanation as to why they rejected the first 4 decimes rating. The recipient, on the other hand, probably did not need or want to know that the weight was over by just a half gram. If anything, they were probably just annoyed that they had to pay twice as much for this particular letter.

Not Just an 1850s Thing

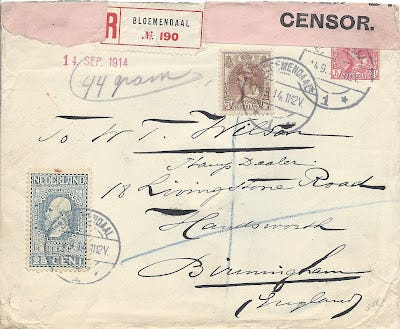

Below is a letter mailed from the Netherlands to England in 1914. World War I was actively engaged at the time, so most mail between nations would go through censors. After the censor read the letter and removed anything they didn't feel should be included, they would reseal the letter with some sort of seal or tape (like the pink you see in the cover below).

This letter carries 37 1/2 Dutch cents in postage. At the top left, you can see the weight "44 grams" written in pencil. I wonder why that is there?

Well, I'm going to work backwards first. The fee to send registered mail from Holland to England was 10 cents (Jan 1881 - Mar 31, 1921). That leaves us with 27 1/2 cents in postage paid by the blue stamp at lower left.

The letter rate for mail from the Netherlands to England was as follows:

1st 20 grams: 12 ½ cents

each additional 20 grams: 7 ½ cts

If the letter weighed 44 grams, we would be in the third weight level, then the postage rate should have been 27 1/2 cents.

As a side note, take a look at the address panel on this envelope - "To W.T. Wilson Stamp Dealer"

Yes, this was a piece of mail to an individual who sold postage stamps to philatelists (people who collect and study postage stamps). That, by itself, could explain a few things - and perhaps that will be worth its own Postal History Sunday someday!

And Other Numbers

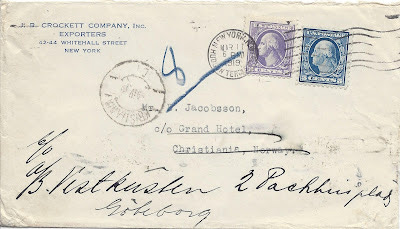

Below is another letter from the same era. This one was mailed from New York in 1919 to Norway.

The postage rate for most foreign mail at the time was 5 cents for the first ounce. Each additional ounce required 3 cents more in postage. This was effective from Oct 1, 1907 until Oct 31, 1953 (that is a very long time for a rate to stay the same!).

Apparently, this letter weighed more than one ounce, but not more than two ounces. Eight cents in postage were applied and a blue "8" was written on the front of the envelope. This time it seems apparent that this was the amount of postage required.

If you have mailed a batch of things recently and there were people waiting, you may have had a postal clerk calculate the amount of postage needed and then write the amount on each item. You would pay the total and they would apply the postage later based on the total written there once the line of waiting customers was gone. It isn't hard to guess that this may have been exactly what happened here.

As is the case for each of the items I shared today, this letter has more to the story. The destination was initially in Christiania (now Oslo) and the letter was forwarded by the Grand Hotel to Goteborg. Is it possible that the blue "8" had something to do with that part of the letter's journey (for example, a hotel room number, as suggested in comments)?

Yes, it is. But, if it is, I have not yet figured out how it would fit. So, until I get to the point where I find out otherwise, I'll stick with my current story.

After all, I am still learning - which is another of the things that appeal to me about this hobby.

-------------------------------

And there you have it - another Postal History Sunday in the books! I hope you enjoyed this little foray into a hobby I enjoy and I hope you also learned something new in the process.

Quick Responses to Questions

I had an additional question asked since last Sunday and I thought I'd do a short answer at the end of this PHS as well.

Who is your audience? Are you writing for people who are already postal historians or are you trying to get people to join the hobby?

My primary answer is that I am writing these Postal History Sunday blogs for anyone who reads them and finds them enjoyable. I am aware of several people who have indicated that they like these blogs, but they do not intend to join the ranks of the hobbyist. I am also aware of others who are respected postal historians and philatelists that have also enjoyed some of these posts too.

In the end, I like to write things to facilitate learning - both mine and yours. And, I like to put nuggets in each post that might appeal to all sorts of people.

An individual who likes postal history, but is at the stage of learning I was at a few years ago might have an "AHA!" moment as they finally find out what some of those numbers are on something they have in their collection.

Meanwhile, someone else will say, "Wow, I didn't know people could send mail prepaid or unpaid - that's different!"

An advanced postal historian might appreciate seeing the effective dates for a particular rate period or details about how a particular rate was calculated.

And others just like the ride.

Whatever your reason, I hope you enjoyed this entry and I hope to see you again next week.

editor note: the description for the 1914 item from Holland to England has been corrected per the comments provided below as of Dec 10, 2021.