Something More... - Postal History Sunday

Welcome to Postal History Sunday, featured weekly on the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with this one (the most recent always shows up at the top).

We have had an extremely busy week at the Genuine Faux Farm, so the energy and time for Postal History Sunday is a bit shorter than it is some weeks. So, this week we're actually going to build a bit more on a couple of prior entries. Every so often, I find new items that fit a topic I've already written on or I learn a new thing or two that makes it worthy of sharing. It doesn't always justify an entire Postal History Sunday, but I still think it might be interesting to give it some space in a shared blog.

Something more for Sorta Paid

Back in June of this year, one Postal History Sunday explored how some postal agreements between France and other nations allowed for partial payment of postage. But, instead of simply collecting the amount of postage the letter had been shorted, there was an additional cost added to the postage due as a way to discourage people from underpaying mail.

During the 1860s, if someone in France wanted to mail a letter to Spain, they would have to pay 40 centimes (French currency) for every 7.5 grams of weight. If someone in Spain wanted to mail a letter to France, they would have to pay 12 cuartos (Spanish currency) for every 4 adarmes in weight (4 adarmes is about 7 grams). And, all would be well if a letter was properly weighed AND properly paid.

It's when someone failed to do just that - for whatever reason - that things get complicated.

The item shown above is a case in point. There are three blue stamps representing 4 cuartos in postage each. That would be a total of 12 cuartos, which paid for a simple letter weighing no more than 4 adarmes. Sadly, this was not enough postage and the recipient in Bayonne, France had to pay more in order to receive the letter.

Our first clue is the marking that reads "Franqueo Insuficiente" (insufficient postage). I took the liberty of using an image editing tool to try to make the lettering stand out a bit more so everyone can see what I am talking about. I admit it. If you didn't have some idea of what you were looking for in the first place, many postal markings are next to impossible to decipher.

We just have to remember that postal clerks dealt with these things daily, so they knew what they looking for (most of the time). And, of course, they probably didn't even entertain the idea that someone like me would want to try to read what a marking says 160 years later.

The other clue is the "2" that is written in blue pencil You can see it in the image above or you can look at the original image of the cover. This tells us and other postal clerks that the letter was a "double weight" letter. It weighed more than 4 adarmes and no more than 8 adarmes. So, the sender should have paid 24 cuartos in postage, not 12.

9 - black hand stamp

90 in blue pencil

Once we figure out that not enough postage had been paid, the next question is "how much MORE postage is necessary to be paid?"

Gee. I'm glad you asked, because that's a question I happen to know the answer to. You can certainly ask any number of questions - I do encourage it - but I can't always guarantee that I'll know much about whatever you ask.

So, how did they calculate the amount due?

First, the payment for remaining postage was to be made in France, which means we need to think in terms of French centimes (cents) or decimes (dimes). Getting right to the chase, the "9" in black ink represents 9 French decimes and the blue "90" is 90 French centimes. Both are exactly the same amount.

In France, the unpaid rate for mail from Spain was 60 centimes per 7.5 grams of weight. Since this was a double weight letter, the cost would be 120 centimes if it were fully unpaid.

The good news? The sender did pay for 12 cuartos of postage, which converted to 40 centimes.

120 centimes - 40 centimes = 80 centimes

Um. Wait a minute, I thought you said you knew what you were doing here, Rob?

Well, actually, I do. There's just a bit more to the story.

Incoming mail to France from Spain was charged an extra 5 centimes

Postage due was rounded up to the nearest decime.

120 centimes - 40 centimes + 5 centimes = 85 centimes

rounded up to the nearest full decime = 90 centimes

And now you know too.

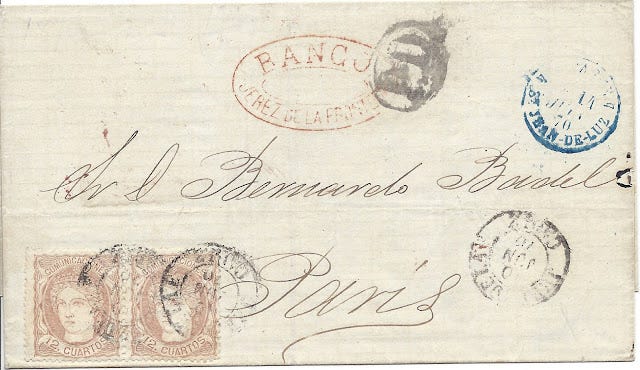

To make sure the story is filled out right and proper, here is a letter that was correctly prepaid 12 cuartos for a simple letter that weighed no more than 4 adarmes. This piece of mail originated in Santander, Spain and was destined for Paris.

A black marking that shows the letters "P.D." tells us that the postage was properly paid - EXCEPT, the recipient still owed 5 centimes simply because the letter came from Spain.

This 5 centime "droit de factage" (drayage right) was a bit of "tit for tat." The Spanish collected a delivery charge of 1 cuarto for all incoming mail from other countries (called "derecho de cartero"). This practice continued despite a postal agreement with France that went into effect on February 2, 1860 that indicated payment of postage should cover all costs to the destination. As a result, the French added their 5 centime fee for incoming letters from Spain (but not other countries).

In both cases, there was no way the sender of a letter could successfully pay the delivery fee, so there was no way to apply a postage stamp to cover that cost - as far as I can tell. Maybe an expert in the field can show me an exception if it exists.

Spain ended their 1 cuarto delivery charge on July 2, 1869 and France followed by removing theirs on July 15.

And here is an example of a double weight letter from Spain to France that was mailed after the droit de factage was removed. There are two 12 cuarto stamps that properly pay for this letter that weight more than 4 adarmes and no more than 8 adarmes. There is no 5 centime marking to indicate a delivery fee.

And, in case you were wondering, the 5 centime fee was always 5 centimes, even if the letter was heavier than a simple letter.

Something more for Borderline Benefits

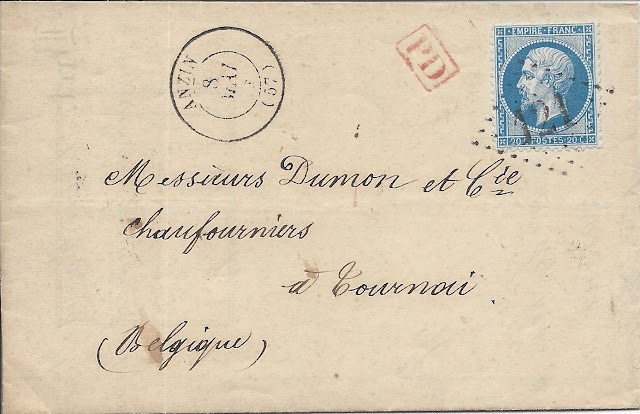

The Postal History Sunday titled Borderline Benefits appeared in February of 2021 and it focused on special postal rates between nations in Europe for communities near a shared border. I do, still, pay attention when I am looking at items that might qualify for these special rates, and here is one that was not shared in that post.

Like so many border covers, the postage stamp design we see here was used on typical domestic mail internal to France. Simply put, there are lots and lots and LOTS of examples of folded letters and envelopes with this blue, 20 centime stamp on it. And, nearly all of them are a simple letter mailed from one place in France to another place in France.

So, the trick is to know how to identify hints that what you are seeing is NOT typical.

PD in a red box

Belgique (Belgium) in address

The first and easiest clue if you are digging through a whole bunch of envelopes and folded letters from the 1850s, 60s and 70s France is to look for the red boxed marking with "PD" (payee a destination - paid to destination). Postal clerks in France used this to indicate postage was paid when the letter was going to leave the country.

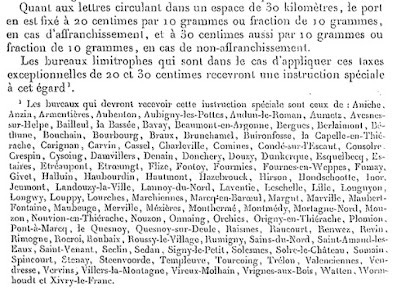

Shown below is text from the postal convention that was in effect as of January 1, 1966 between France and Belgium. It sets the border rate at 20 centimes per 10 grams in weight, instead of the 30 centimes for all other mail to Belgium from France. To be eligible the distance could be no more than 30 kilometers from the origin to the destination.

Click the image to see a larger version

This document includes a list of French communities that were eligible for this reduced rate if the destination was within the 30 kilometer distance. The town of Anzin is the second one on the list - and that's where this letter came from.

The other challenge, of course, is to be able to read the address. If you know the letter started in France and the address says it is going to Belgium, you should take notice!

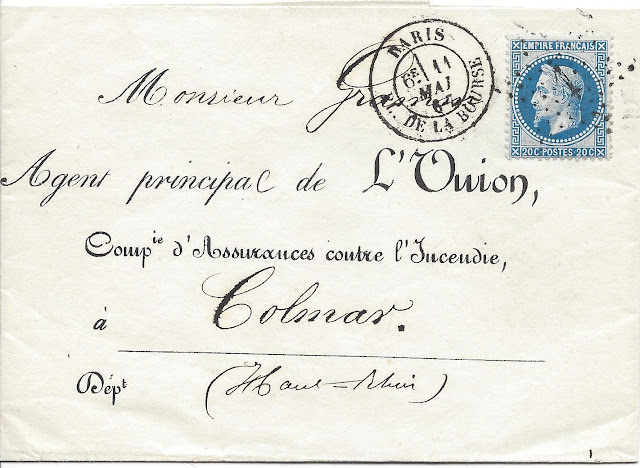

Here is a letter mailed from Paris to Colmar (also in France at the time). I put this one here to illustrate two possible confounding factors that might make it hard for a person to immediately see that a letter is being sent to a different country.

The first, of course, is hand-writing. It can be neat - or not. This letter actually has a pre-printed address except for the city and the department. Colmar is pretty clear, but "Haut-Rhein" is a bit less so.

And of course, you have to know your geography or be able to find period maps to help you learn that geography. Sometimes a scrawl is just a scrawl until you find something to help you figure it out.

And then, you need to be able to acquire a bit of regional history.

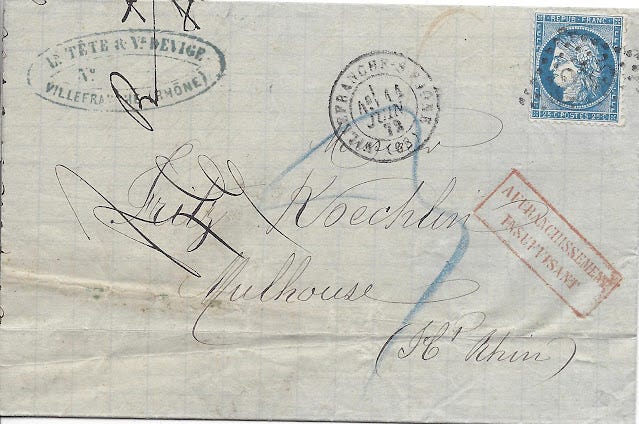

Mulhouse, the destination town for this letter, is very near to Colmar. Both are in the Haut Rhein. Can you see where that department name is written on this folded letter? If you can't, look at the last part of the address and you'll see "Ht Rhin."

In the 1860s, when the first letter was mailed, Haut Rhein was in France. But, after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, that area was ceded to Germany. Suddenly, Mulhouse and Colmar were in another country and foreign postage was necessary if a person in France wanted to send a letter to those communities.

What we see here is a case where the person sending the letter probably did not personally accept that Mulhouse was no longer in France. They put a 25 centime stamp on the letter and sent it on its way - and they very deliberately (I think) did not indicate that Mulhouse and Haut Rhein were in Germany.

The French postal clerks knew better, even if they might have sympathized with the sentiment. They put a red boxed marking that read "Affranchissement Insuffisant" (insufficient postage) on the front. Then, the German postal carrier in Mulhouse collected 3 German groschen from Fritz Koechlin,who probably was a bit less than pleased with the sender at this point.

While Fritz might have been displeased in 1872, I am hopeful that you are currently feeling a bit more pleased about your own life in the present day. Perhaps you found Postal History Sunday to be a pleasant diversion that allowed you to enjoy a few moments before you return to whatever it is you must do?

I appreciate your willingness to visit, read, and maybe learn something new. I am always happy to accept questions - even some I cannot answer - and comments or corrections. I hope you have a good remainder of your day and a fine week to come.