Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

Those of you who have been here before and are already comfortable with the process - you know what to do! Set your troubles aside, grab a favorite beverage (and maybe a snack), and put on some fuzzy slippers.

For those who are new or who like refreshers, this next bit is for you! Postal History Sunday started as a pandemic project in August of 2020. I was asking myself how I might help others during that difficult time and decided that I could write and freely share that writing. One topic that took hold was something I enjoy - postal history. My goal was to provide articles with the intention of making the content accessible and interesting to individuals regardless of their experience with the hobby/topic.

Today, Postal History Sunday’s audience includes people who are recognized experts in postal history as well as individuals who have stated that they don’t intend to participate in the hobby, but they still enjoy these writings.

Now, it also includes you - with all the unique perspectives you bring.

And you are welcome here!

With that preamble complete - let’s see what kind of interesting things we can explore today!

Illustrated Covers as a Window for History

Today we’re going to start with an envelope that is well over 100 years old and has interesting and colorful illustrations. This piece of postal history was mailed at 10:30 AM on March 9, 1906 in Cambridge, New York - as evidenced by the postmark next to the 2-cent postage stamp. A receiving postmark on the back tells us it arrived in Newburgh (also in New York) at 6 PM on the same day.

Not bad. Same day arrival for a letter that had to travel around 125 miles. With a 6PM arrival, I am guessing the letter was delivered to the addressee by a letter carrier the next day in Newburgh. The arrival postmark merely records when the receiving post office processed the letter, it does not necessarily tell us it was delivered at that time. So, unless Newburgh had an evening postal carrier delivery, Mr. Darwin W. Esmond (1845-1923) didn’t see this until the 10th.

The letter rate for mail being sent from one location in the United States to another was 2 cents per ounce (July 1, 1885 - November 1, 1917). Evidently, this envelope and its contents did not weigh more than one ounce, so the 2 cent postage stamp was enough to pay the postage. Postal historians call items like this simple letters. There were no special services, such as registered mail. It was properly paid and it did not weigh more than one multiple of the rate unit (an ounce). A simple letter is the most common type of letter mail a person can find from the 1850s through the 1900s.

So, you might be asking yourself, “Why in the world are you starting with something that you’ve just identified as common? Why not something that’s special?”

Well, that’s a fair question. I guess I’ll have to answer it.

Sometimes the thing that is interesting about a piece of postal history has very little to do with the postal aspects of the cover. In this case, it has much more to do with the Jerome B Rice Seed Company and the illustrations they placed on this envelope.

Both the front and the back of this envelope have colorful illustrations promoting the seed products this company was offering in 1906. And, with a mailing date in March, it isn’t hard to relate to the Spring ritual of selecting seeds for the coming growing season. However, envelopes with this much illustration from the early 1900s are not the norm for mail at the time. The vast majority bore no additional ornamentation beyond an address, postage stamp(s) and a postmark or two.

Perhaps the other bit of information people might need to know is that I am also a diversified, small-scale farmer who raises a variety of vegetables and poultry. I enjoy finding covers that connect with this part of my life. And I find this cover amusing partly because it features both peas and cucumbers on the back of the envelope. One of our farm’s early taglines was “Minding Our Peas and Cukes.” That sort of silliness does lead me to other word play, so it isn’t too hard to see the connections I draw to this cover.

If that doesn’t amuse you, let me also point out that one of our intercropping techniques is to put our cucumbers near pea rows. Peas are planted earlier and establish themselves before it gets warm enough for cucumbers to go into the ground. The peas provide a location for predators of the cucumber beetle to get established and in place by the time cucumbers are planted. It’s just one of the ways we control pests on our farm.

Jerome B Rice Seed Company

The Jerome B Rice company has its roots in a local Cambridge seed business started by Simon Crosby in 1816. Crosby’s seed business soon became one of the largest employers in the area. Around 1845, Roswell Niles Rice purchased the Crosby seed house and combined it with his own traveling seed sales business. In 1865, Roswell’s son, Jerome Bonapart Rice, joined the business once the Civil War in the United States was over. The business took on the the name Jerome B Rice in 1886.

The Jerome B Rice Seed Company was a growing and successful firm in the early 1900s and included farms for seed production in Illinois and Michigan (and possibly elsewhere?). It was eventually purchased by Associated Seed Growers (Asgrow) in 1939. Asgrow would move away from garden and flower seeds and are known for developing Roundup Ready soybeans. Bentley Seeds can make the claim for continuing the garden and flower seed packet business in Cambridge. Their website states that they took over the Asgrow operations there in 1975.

The Jerome B Rice Seed Company calls attention to itself today because of the colorful illustrations they used to promote their seed house, including the gnome-like figure happily harvesting an Early Winningstadt cabbage. They also created trade cards featuring “vegetable people” that are popular with collectors of various historical paper materials.

Rice was born in 1941 and attended Albany Business College. Like many young men of the time, he enlisted in 1861 as part of the 123rd New York Volunteer Infantry. He was injured and captured at Chancelorsville and spent time in Libby Prison. As a result, Rice spent much of his later life in a chair, unable to walk. In addition to serving as president of his own company, he was president of the area’s agriculture society and was in several other positions of prominence. Rice died in 1912 at the age of 70.

A quick note about resources if you wish to learn more

The previous section is a summarization of material from several sources, including those linked in the prior paragraphs. Initially, this blog by Emma Craib drew my attention to the History of Washington Co., New York- 1878. I then located a brief biography of Jerome Rice in “New York state men : biographic studies and character portraits” ( ed. Frederick S. Hills, vol 2, page 100). Interested persons can take the link under Rice’s portrait for more detail than what I provide here.

Wheel Hoes and Push Seeders for the Win

The illustration above shows an individual using a tool known as a wheel hoe to cultivate onions at one of the Jerome B Rice farms. The basic idea of a wheel hoe is to reduce the strain on the human body by allowing the worker to stand upright and use the bigger (and stronger) muscles to do most of the work. Depending on the model, a blade or tines are positioned behind the wheel to disturb the soil and discourage weed growth.

By showing you this image, it gives me an excuse to show you a second cover!

Aren’t I clever? (Don’t answer that.)

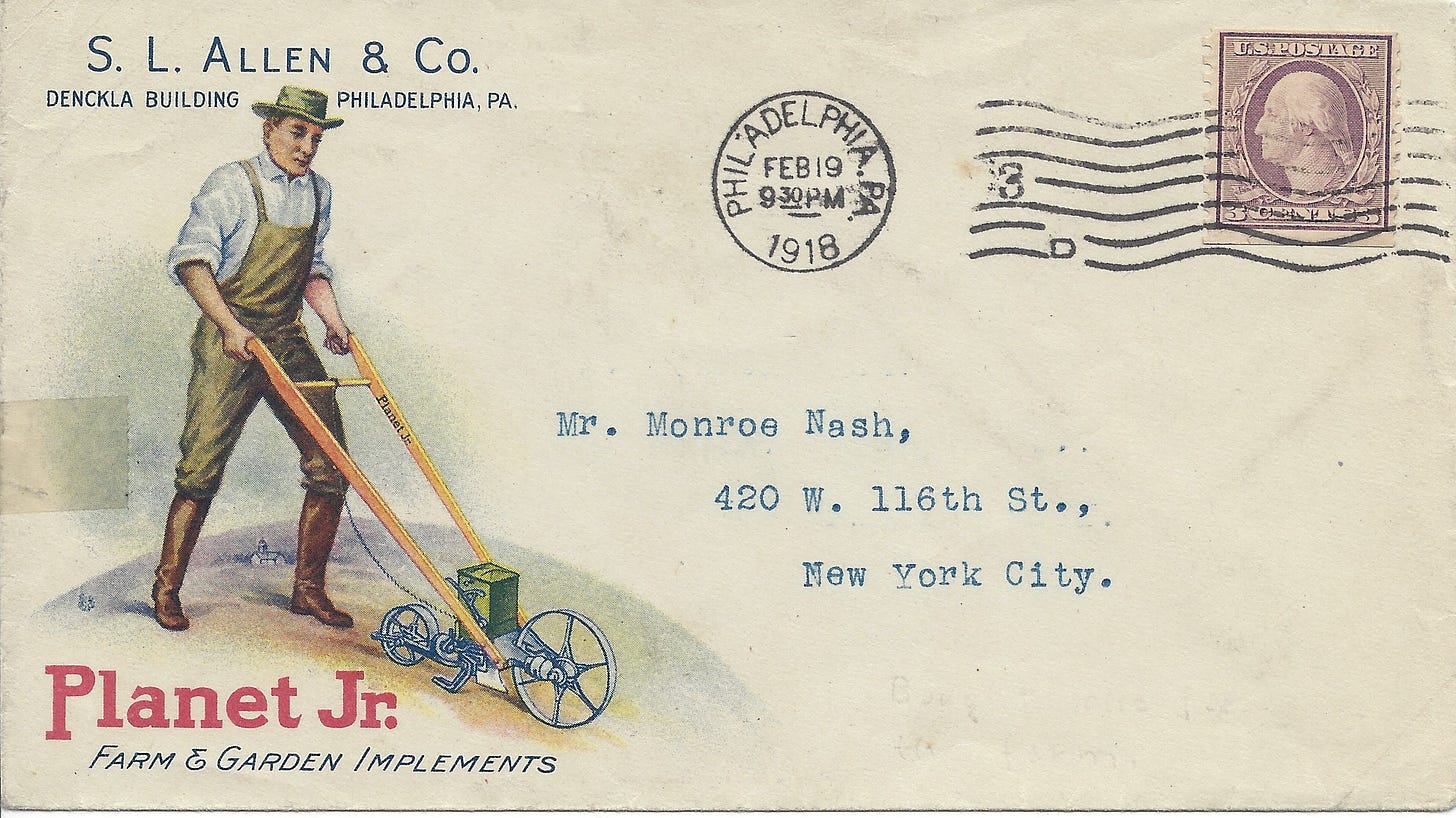

Together, these two covers illustrate a small bit of postal history that could be tempting to overlook when we concentrate on the colorful images. This simple letter, unlike the first, bears a 3-cent postage stamp, instead of a 2-cent stamp. The letter mail rate was temporarily increased to 3 cents per ounce during World War I (November 2, 1917 - June 30, 1919). While the war ended in November of 1918, the “war rate” continued for a while. Starting in July of 1919, the postage rate would return to 2 cents per ounce until 1932.

The front of this cover illustrates a Planet Junior push seeder. Even today, there are vegetable growers who seek out older Planet Junior tools for use on their farms. In fact, this design has been adapted several times by other companies and successfully marketed. We use a tool at our farm that is called a European push seeder and has many similar characteristics.

Like the wheel hoe, the push seeder allows the grower to stand upright to reduce the probability of repetitive stress injuries. The most difficult part of using this tool is identifying the correct seed plate for the crop you intend to plant.

Please note. I will not deceive you like some of those advertisements for exercise machines that tell you using them is effortless. First of all, if exercise is effortless, there is little to be gained from it. There is still plenty of effort (and walking) with push seeders and wheel hoes. But, they sure do beat bending over or crawling thousands of feet to set each seed in the ground by hand!

And here’s the connection to the J.B. Rice image of a person cultivating onions in Michigan. Our second cover shows an illustration of five individuals pushing straddle wheel hoes to cultivate a field of, presumably, vegetables. Either a blade or some sort of tine implement would be behind each wheel (and on either side of the crop). The idea is to cultivate as close to the row as possible without damaging the crop.

The wheel hoe I prefer using has a single wheel with a stirrup hoe behind it. So, when I wheel hoe I walk on either side of the row to get as close as I can to the vegetable crop. I have also used a wheel hoe similar to the one shown above, but I learned using the single wheel and have become quite proficient at it. I actually find the straddle wheel hoe to be uncomfortable because you have to walk with your feet a bit further apart to avoid stepping on the crop.

You know what? These colorful covers feel like a good way to celebrate Spring. So, let’s do one more!

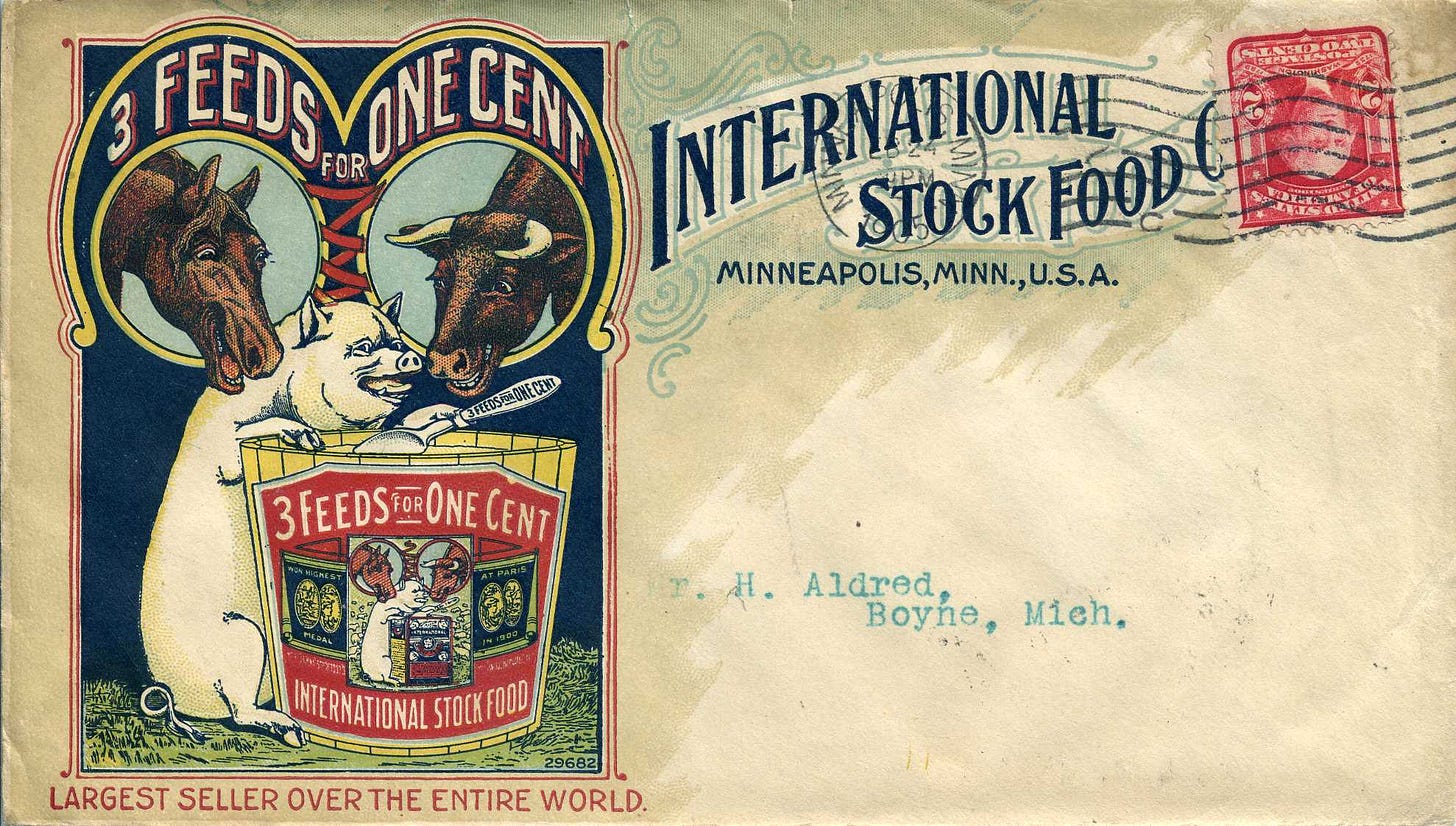

This advertising cover from the International Stock Food Company in 1905 certainly catches the eye. And, if you do any work with animals, I think you would agree with me that it is highly unlikely that pigs, cows and horses would ever smile like this. I don't think their facial muscles work that way.

As far as the three feeds for one cent, it isn't entirely clear to me what they meant by it. Do they have three types of feed that are mixed differently for different livestock and they all have the same price? How much would I have gotten for a penny?

After doing more research, it seems this company did more with producing supplements to be added to whatever the animals were eating. So, if you pasture raised animals, they might suggest adding this to their diet. Or, if you were feeding your horses oats, they might suggest mixing one of these products with the oats. I suspect, if I really wanted to, I could figure out more details than any of us really care to know!

The International Stock Food Company still exists and is currently based in Canada, but at the time this cover was mailed the main factory was housed in Minneapolis, Minnesota (with another in Toronto). The building there had formerly been an exposition building constructed in 1886 and it housed an International Exposition that same year. It was also the site of the 1892 Republican National Convention. The building was used as an entertainment venue until Marion Willis (Will) Savage purchased the building in 1903 for his growing feed business.

Will Savage grew up in West Branch, Iowa, and worked as a clerk at the drug store. His products took advantage of his pharmaceutical knowledge, allowing him to develop supplements for a wide range of livestock. Savage also owned race horses, using their success to promote his feed business. He purchased a horse named Dan Patch for $60,000 in 1902 and that same horse set a record that would stand for almost 50 years at the Minnesota State Fair in 1906.

Thank you for allowing me this opportunity to celebrate Spring. Maybe in the coming weeks we’ll look at a few more related items. We’ll see which way the wind blows me as I consider what to write about next! And, let me remind you all that I will happily answer questions and gladly accept corrections should I make an error.

Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come!

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I cannot believe how beautiful those covers are!