Swiss Missed

Postal History Sunday #226

As an individual who has done a significant amount of writing and speaking in my lifetime, I find I have a greater appreciation of and expectation for mistakes. If you don’t quite understand what I am getting at, consider how many times you misspeak during one day in normal conversations. Now, think about how it might feel if the words you say - and the one’s you say wrong - are witnessed by thirty (or three hundred) people.

I am reminded of the time when I was giving instructions in a class and forgot to utter the word “NOT” in front of a key phrase. Or that moment when the word “calculation” suddenly made my tongue think it required gymnastics not previously encountered by my person. And verbal miscues are only part of the equation - I’ve got 224 Postal History Sundays (now 225) where there are multiple opportunities to err.

They say “to err is human,” but there is still nothing quite like the internally (and sometimes eternally) held embarrassment that comes with typos, bad word choices, and incorrect information in a written text.

This might be why I feel a certain level of satisfaction when I discover a postal history item where “mistakes were made.” In today’s Postal History Sunday, we’re going to explore just such an item. So, push your own foibles aside (oooo! I used the word “foibles”!) and put on the fuzzy slippers. Grab a favorite beverage and enjoy today’s article.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way

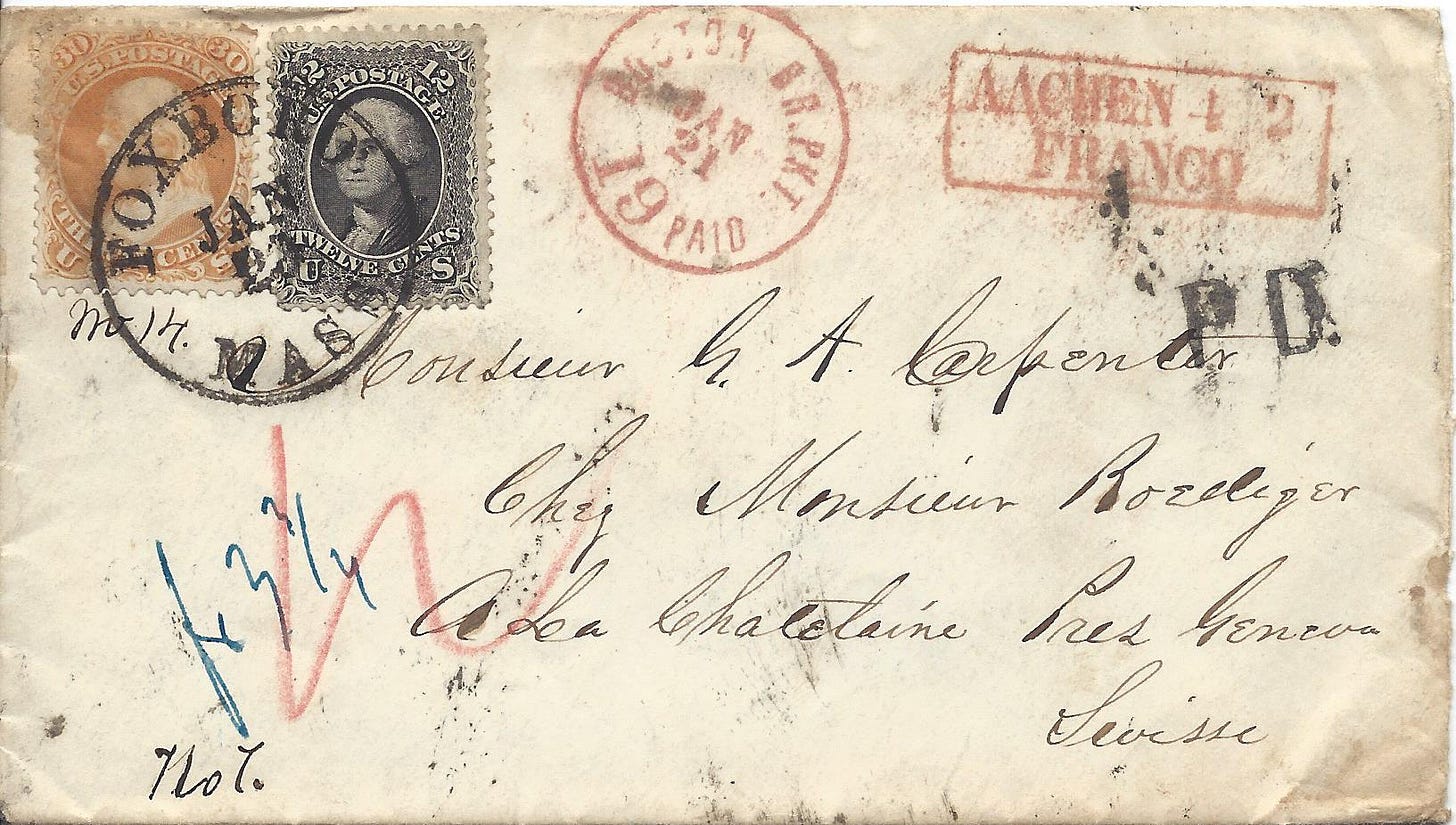

Today’s focus item is a letter that was mailed January 20, 1863 at the Foxboro (MA) post office. The goal was to get this missive from Foxboro to G.A. Carpenter in Geneva, Switzerland. The highly abbreviated story for this item is that it got there - eventually.

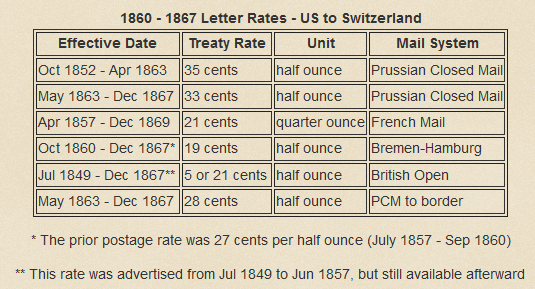

The less abbreviated story is that the letter was probably intended to get to Switzerland via France. The 42 cents in postage stamps would have properly paid for a double weight letter through the French mail. Instead it went via the Prussian Closed Mail where it was also fully paid.

I guess that’s what happens when the letter writer opted NOT to put a docket instruction on the envelope.

However, something went wrong on the way to Geneva. Instead of stopping in Switzerland, it went through it - on the way, I presume, to Genoa, Italy. The mistake in routing was eventually discovered and the letter was redirected to Geneva and G.A. Carpenter.

This cover has the makings of an excellent Merry Chase. While I am sure there were some who were bothered by the mistakes that sent it on this journey, you and I can have a little enjoyment at their expense.

Setting the stage - getting it right

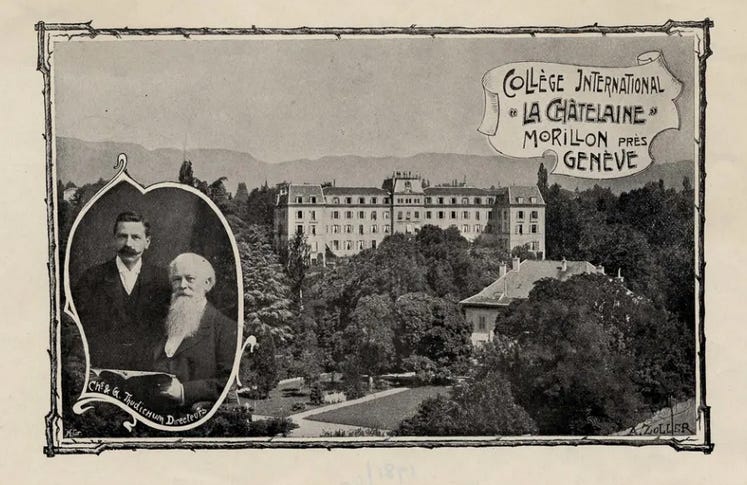

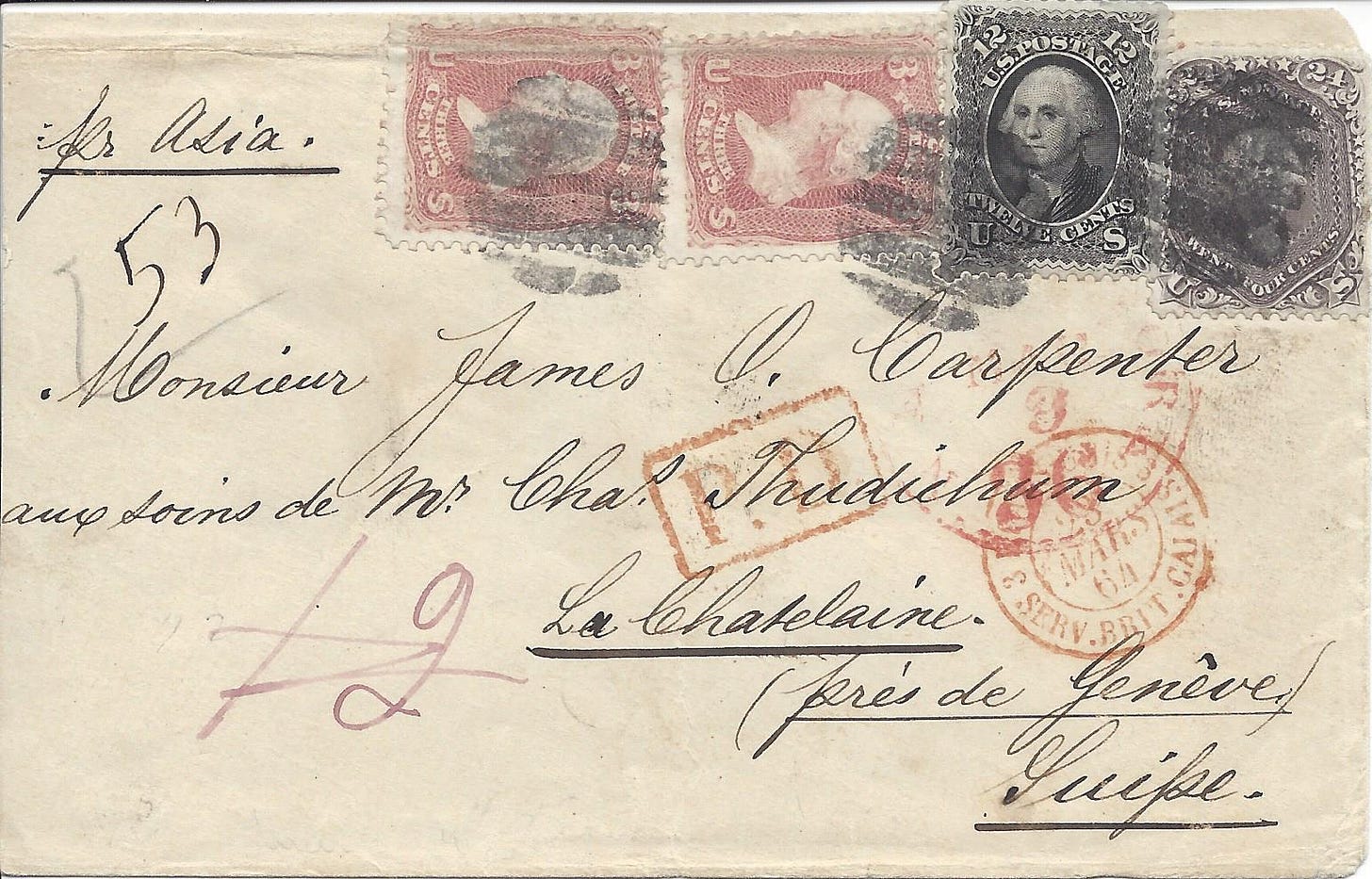

Before we talk about what went wrong with our first cover, I wanted to show you a similar item where things went right. The comparisons between the two is particularly useful because both items were addressed to international boarding school students (probably related) in the canton of Geneva. La Chatelaine (also known at the Thudichum Institute) was an exclusive school for ten to eighteen year-olds.

Like the first cover, this one has 42 cents in postage applied. But, unlike the first item, this letter did get to Switzerland via the French mail. The postage rate was 21 cents per 1/4 ounce (Apr 1857 - Dec 1869), so this letter must have weighed more than a quarter ounce, but no more than 1/2 ounce.

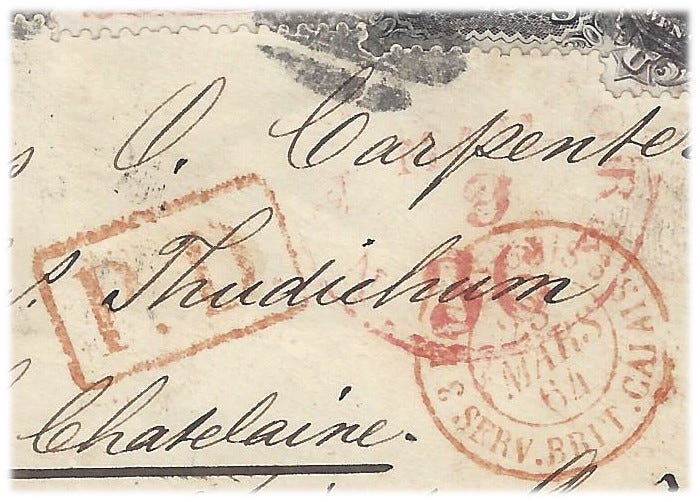

The red markings that appear just under the postage stamps confirm that this letter was sent under the US-French Convention of 1857. The large, incomplete marking was applied at the New York City exchange office. The March 9 date matches the sailing departure of Cunard Line’s Asia, which arrived at Queenstown (Ireland) on March 21.

The number "36” in the New York marking tells us that 36 of the 42 cents collected was to be passed from the US to the French. The French then used that money to pay the British for the trans-Atlantic voyage and transit across the English Channel. They also passed the appropriate amount of postage on to the Swiss for their portion of the expenses. The US got to keep six cents for their own efforts

The other red markings shown here were applied at the French exchange office (on the train from Calais to Paris). This letter was taken out of the mailbag on March 23 and it was sorted to go to Geneva, Switzerland - where it arrived the next day according to a receiving postmark on the back of the envelope. All in all, it was a trip of fifteen days to get from New York to Geneva.

There is also a “12” written in magenta ink at the bottom left that is a bit of an oddity. This would have been the correct credit to Prussia if this letter were sent via Prussian Closed Mail to get to Switzerland. So, it is likely the clerk at the New York Foreign Mail Office considered that route, but crossed off the credit when it was decided the route via France would be better.

How were the Swiss missed?

That brings us back to the letter that somehow went through Switzerland and into Italy before it was redirected back to the proper location. The question, of course, is “how did it happen?”

Like the second letter, this item properly paid for a double weight letter via the French mail to get to Geneva. It just didn’t go that way.

The first hint that something was wrong

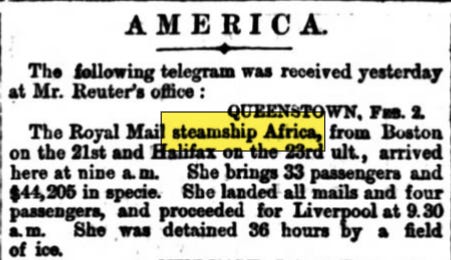

Our first letter originated in Foxboro, Mass, instead of New York City as our second letter did. So this item went to the exchange office in Boston. The clerks there applied an exchange mark dated January 21 (1863), which is the date the Cunard Line’s Africa was due to depart Boston Harbor.

However, the credit marking “19 paid” was an odd choice. This would have been the proper amount for a letter that was going to the United Kingdom, not Switzerland. If it were going via French mail, the amount would have been 36 cents (as we saw before). The proper credit for Prussian Closed Mail was 12 cents.

Because the incorrect credit marking was applied by the Boston clerk, it makes it plausible to think that the problem started here. Because there is no British exchange marking, it wasn’t bagged with other items that went to the British mails. There is a Prussian marking, so we know it went that way. Did they bundle it with other letters bound for Italy through the Prussian Closed Mail?

A rough Atlantic crossing

It is interesting to note that the Africa took a little bit longer than usual to cross the Atlantic - maybe a day or two longer than normal. According to the Hubbard & Winter’s North Atlantic Mail Sailings (page 49), after a day of sailing east, it was discovered that the shaft that drove the screw (to propel the ship) was cracked. As a result, the steamer spent some time making progress under sail since most steamships maintained the ability to use sails if the engines failed. Apparently, they were able to come up with a repair that prevented further delay.

Unfortunatley, I was not able to confirm this by searching period newspapers. Instead, I found this:

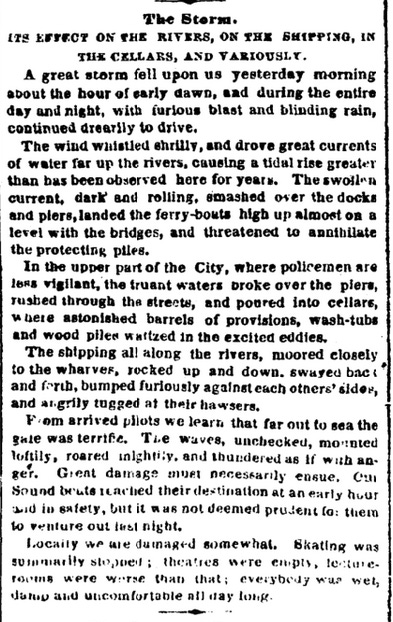

The Africa might have had a rough departure as it left port on the 21st, possibly sailing into a gale that was causing damage on the east coast of the US. The coast from New York City down into Virginia were impacted. Since the steamship left from Boston, it might have been able to pass on the northern edge of the storm.

However, the storm of January 20/21, 1863 had other consequences that had nothing to do with our letter.

After the Army of the Potomac had lost at Fredericksburg (US Civil War), General Burnside saw an opportunity to flank Lee’s army by crossing the Rappahannock River at Bank’s Ford. After a successful day’s march on the 20th, the rains began to fall. Undaunted, Burnside pushed forward. Soon, the roads were churned into a muddy, impassible mess. Equipment sank up to the axles and could not be moved. The foot soldiers had to rest every hundred feet and everyone, soldiers and animals, dealt with temperatures in the 30’s while being drenched with rain.

The Mud March continued until the Union troops got to their destination, only to find the Confederate forces waiting on the other side of the river. Burnside issued the order to retreat, but that meant returning on the same roads and paths that had been destroyed in the process of getting there.

It was certainly a big enough weather event that it would provide a reasonable excuse for a shipping delay. But, then I found this:

The stated explanation for a 36 hour delay was that the Africa encountered a field of ice. Not a storm. Not mechanical problems.

Or maybe, it was all three and the captain just didn’t want to spend extra time running over the litany of issues they experienced on this Atlantic crossing.

Perhaps this was an indication of what was next for this letter?

Credit markings giving clues

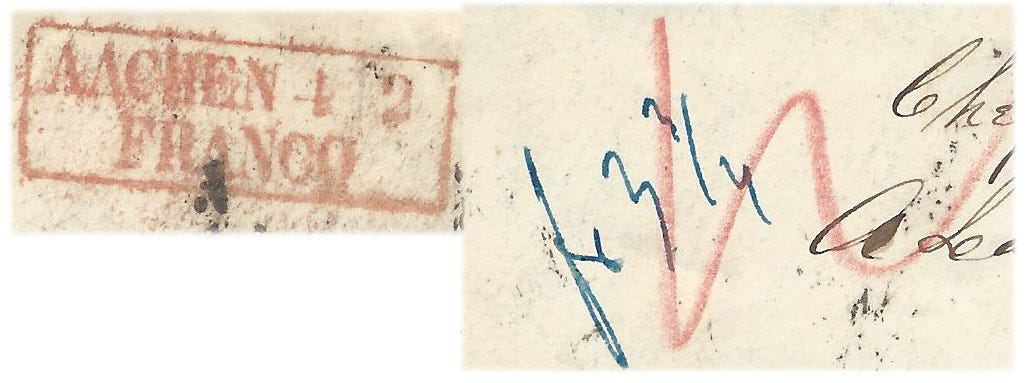

I took a moment to separate the relevant markings in hopes that it would make this next part easier to understand. The boxed marking that reads “Aachen 4 2 Franco” tells us that the letter was taken out of the mailbag at the Aachen exchange office (which was actually the train between Verviers (Belgium) and Coeln (Prussia) on February 4. “Franco” tells us that they recognized the letter as paid.

This tells me that the clerk in Boston decided to send this letter to Switzerland via the Prussian Closed Mail. The postal rate for that route was 35 cents per 1/2 ounce (Oct 1852 - Apr 1863). As a result, this letter was overpaid by seven cents. Perhaps the clerk had knowledge about a delay that would slow this letter if it went via France. That’s probably a problem for me to research on another day.

The markings in blue and red, shown at the right, tell us how some of the postage was distributed. The blue marking reads “fr 3 3/4” for 3 3/4 silbergroschen and was probably applied in Baden (I will accept corrections here if I am in error). This marking is known as a weiterfranco - or an amount passed forward by the Prussian Mail to the Swiss and Italian systems. The red crayon marking was applied by the Swiss and is a “12” that represents the 12 kreuzers passed for transit through their country and the Italian postage (6 kr each).

The significance of both of these markings is that both the Germans (at least in Baden) and then the Swiss thought this letter was intended for Italy. So, the question is - were they perpetuating an error started in Boston OR did the Prussian mail clerk on the Verviers to Coeln train make the mistake that led to a trip to Italy?

Even more errors?

Last week, our Postal History Sunday article focused on transit markings and I made the point there that each marking respresented a point where postal clerks handled the letter for some reason. Typically, that reason was to sort the letter to the next correct mode of transportation to get it to the eventual destination.

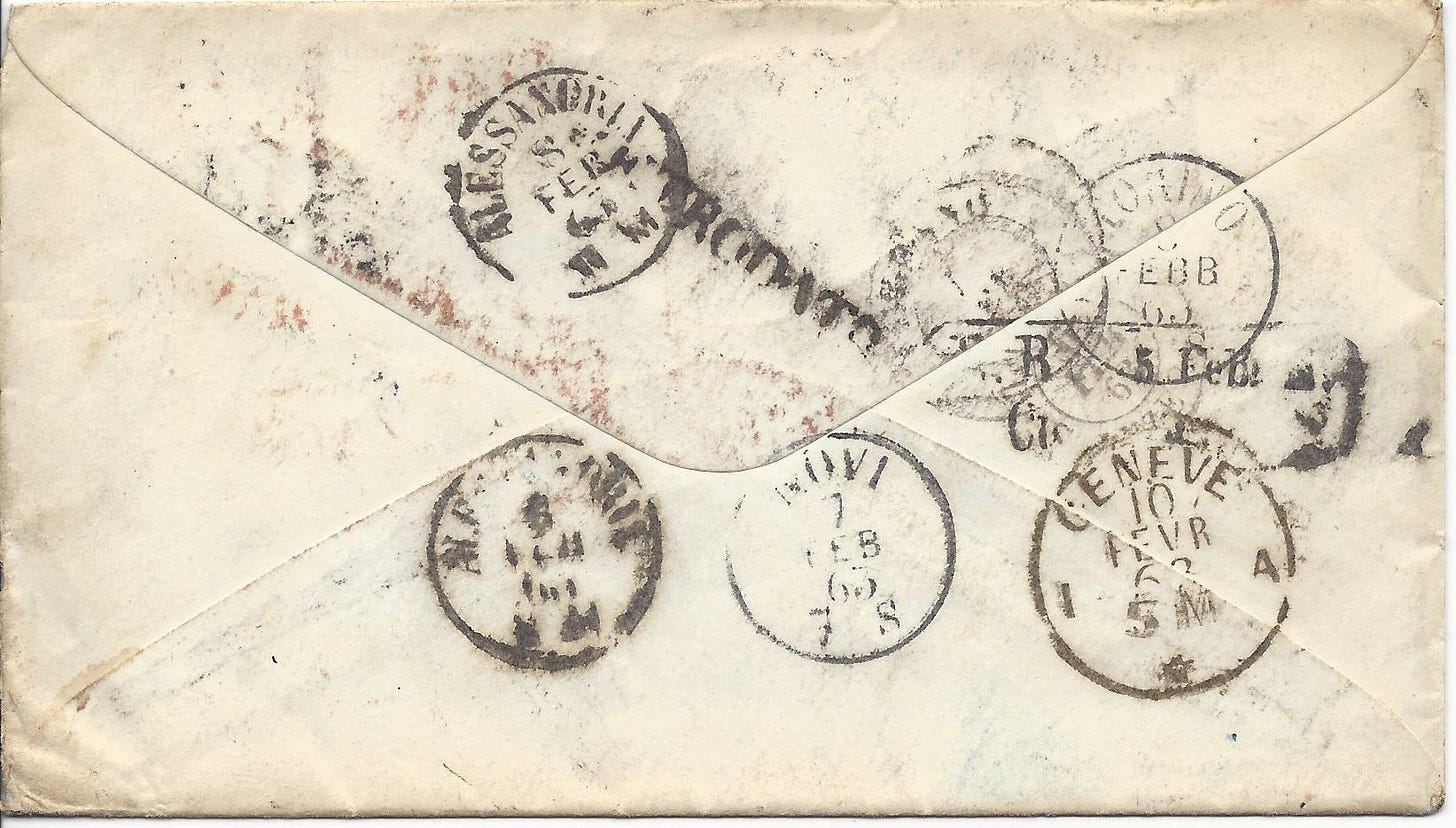

If we look at the back of this cover, we see there were numerous points where this particular letter was processed and resorted. Each of these markings indicates an opportunity for a clerk to recognize that the letter was being sent the wrong way.

Some of the markings are impossible to read, but I will attempt to give you a rundown here (including the markings on the front of the cover):

US: Foxboro, Mass : January 20

US: Boston, Mass : January 21

US - Ireland: Cunard steamship Africa : January 21 - February 2

Ireland: Queenstown (no marking) : Febuary 2

Prussia: Aachen : February 4

Baden: E.B. Curs (long box marking on back for Baden railway) : February 5

Switzerland: Undetermined Swiss marking (possibly Luzerne) : February 6

Switzerland / Italy: Verbano (?) : February ?

Italy: Allesandria : February 6

Italy: Novi : February 7

Italy: Retrodato (single, straightline marking)

Italy: Allesandria : February 8

Italy: Torino : February 8

Switzerland: Geneva : February 10

I think that qualifies as a Merry Chase!

Finally, they figured it out!

It is not clear to me whether the problem was discovered in Novi (just north of Genoa) or if it made it all the way to Genoa before the letter was turned around and sent back to Switzerland.

The problem was finally discovered at the point it became clear that the address was not Genoa. The RETRODATO marking can be found on letters that are forwarded or otherwise redirected in Italy during this time period. In this case, it resulted in this cover being reposted to the intended Swiss destination.

Sadly, for all of their effort, the Italians probably had to pass 20 centimes back to the Swiss according to their postal agreement. That amount is equivalent to 6 kreuzers - which means the Italians got no postage credit for their efforts, brought about by no fault of their own.

Why were the Swiss missed?

There are two more questions that come to mind, now that I have outlined the Merry Chase:

Where was the initial mistake made that resulted in the letter going to Italy?

What might have caused that mistake to be made?

It is my opinion (and it is only an opinion) that the Boston exchange office made the initial error and it was perpetuated by each of the following postal systems until it became apparent that it was going to the wrong place. However, it is just as likely that the mistake originated at the Aachen exchange (Prussian) or on the Baden railway. What is clear is that the Prussians and/or Baden thought the letter was destined to Italy, based on the weiterfranco marking of 3 3/4 silbergroschen.

To understand why this was an understandable mistake, consider that Genoa is also known as Genes (French), Zena (Ligurian), and Genova (Italian). For more of this sort of thing, check out PHS #209 - London is Londres to the French and an Italian might send a letter to Filadelfia. Once you understand that, you have to recognized that a letter to Genoa could have its address written in any of the other ways (Genes, Zena and Genova) and it would be expected to get to the right place.

Genova and Geneva are not all that different - with only one letter difference. And given different people’s hand-writing, it isn’t too hard to see how someone might make the mistake. It does, however, require that that clerk completely fails to see the word “Suisse” (Switzerland) on the address panel.

I guess that’s why we call them mistakes.

The other possible reason for confusion is that there was also a 42-cent rate for mail to Italy via the Prussian Closed Mail. It’s not so difficult to believe that a busy Boston Foreign Mail clerk glanced down and saw “Genova” instead of “Geneva” and automatically equated the 42 cents in postage as a letter to Italy via the Prussian Closed Mail.

But that still doesn’t explain the Boston exchange marking with the wrong credit amount.

Let’s just say that mistakes were made, but the letter did get to where it was going in the end.

The Carpenters and La Chatelaine

Today’s second letter - the one that did not “miss” Switzerland - provided me with enough information to learn more about the addressee and the school he went to. James O. Carpenter’s (b. 1848) obituary for March 7, 1905 was published in the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union and can be accessed here. The contents of that obituary were enough to confirm the destination for both of these letters.

James Oliver Carpenter was born in Foxboro, Massachusetts - which makes it likely that G.A. Carpenter was related since his letter comes from Foxboro. The obituary states that James was either 11 or 14 when he began attending the “International School at La Chatelaine, Switzerland.” At the age of 17 (1865), he returned to the US to work with his father who was, “at the time, the largest manufacturer of straw goods in the country.” That company would merge with others to become larger company named the Union Straw Works under the direction of E.P. Carpenter.

James spent a couple of years in China as an exporter of Chinese straw braids - a craft that has a long history. He would marry Alena F. Lyon, daughter of William H Lyon and worked for his father-in-law’s fine imports business until 1887, when he retired.

La Chatelaine was an active boarding school from the 1860s into the early 1900s. It served as a temporary hospital for French and Belgian Prisoners of War captured by the Germans in World War I before being converted into the Hotel Carlton in 1926. La Chatelaine again served a humanitarian purpose during World War II. Renamed Le Centre Henri Dumont, it housed displaced children until the conclusion of the war.

After the war, the building was given to the International Committee of the Red Cross by Swiss federal and cantonal authorities. The ICRC continues to use this building and the surrounding area to this day.

Thank you for reading Postal History Sunday! Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Whew, that was intense! How long did it take you to compile all the background data for the missent cover?