Welcome to Postal History Sunday! I hope you take the opportunity to enjoy learning something new - or at least you like to be entertained by a person who thoroughly enjoys their hobby. Either way, this isn't a half bad way to spend a few moments of your day.

In this edition, I wanted to revisit the topic of dockets on postal history items. The last time I did so, Postal History Sunday was only a few months old. I'd like to think I've learned a thing or two since then.

So, let's get to it!

What's a "Docket?"

Postal historians and postal history collectors often reference docketing on various mail pieces, which can take various forms. Docketing would be some sort of handwriting on the letter or piece of mail that typically provides record-keeping functions for the recipient OR directives to the postal services.

And, of course, postal historians are usually more interested in the directives - but the record keeping can provide useful clues too.

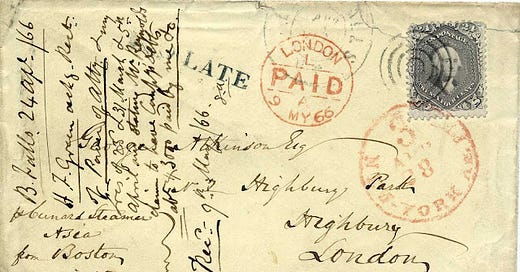

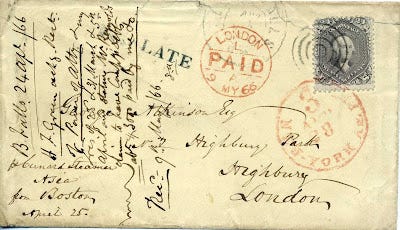

For example, the item above shows lots and LOTS of docketing.

The writing that runs sideways on the left side of the envelope are filing notes by the recipient. George Atkinson, Esq, a lawyer by trade, probably did what many at the time did - they filed documents and stored them in the envelope they came in. To provide for easy reference, they recorded the date and origin of the contents, a brief summary, AND the date the letter was received in their office (May 9, 1866). It just so happens this date matches the London marking showing in red towards the top.

This method of filing is part of the reason postal historians have as much material to collect as they do. It also explains why many of the same addressees keep showing up on these pieces of mail.

The other handwriting on the front of this letter includes the address AND some directional docketing at the lower left. This docket reads:

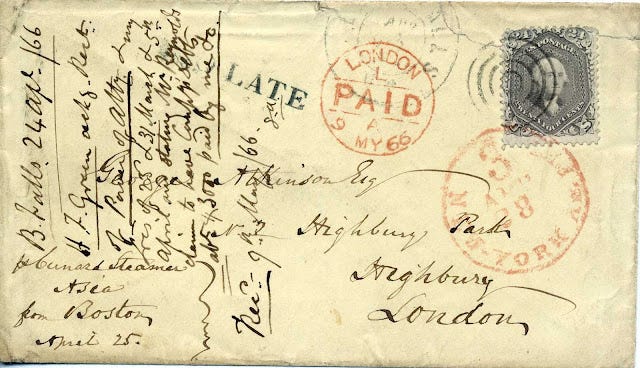

"per Cunard Steamer Asia from Boston April 25"

At least - that's what the writer was hoping when they mailed the letter. It turns out - if you read the New York marking in red at the right side - that it left New York on April 28 on a steamer that was NOT the Asia.

We'll get back to that in a bit!

Success and Failure in Directional Dockets

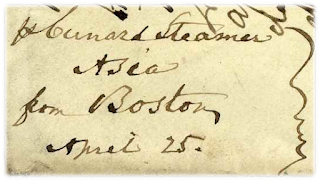

If you look long enough, you can find all kinds of docketing on the mail that clearly was meant to try to direct the post office with varying degrees of success. Take the item below for example.

Other than the address panel at the center of the envelope, there is a very brief docket at the top left.

The docket "per Steamer" at the top left could have meant one of three things.

There was more than one option for mail to go from Worcester to Boston

The writer thought there was some other option than a steamship to cross the Atlantic

The writer just wanted to write "per Steamer" on the envelope

I can tell you that Worcester is just west of Boston and there are no rivers that would have had steamers plying between the two locations. I am pretty certain a train or a coach carried the letter to the Boston foreign mail office. So, it wasn't the first option.

I am ALSO quite certain that the letter rode on a steamship (a Cunard Line ship) to cross the Atlantic. In fact, there really wasn't another way that mail would do so at the time. So, you could argue that the person who wrote this wasted ink on the docket.

In other words - I would choose option three (they just wanted to do it).

In their defense, it had not been that many years that steamships were the primary mode of transportation across the sea. The first use of steam power to cross the Atlantic was in 1819, but much of that trip was powered by sail. And it wasn’t until the 1840s that it became more common for steamers to carry the mail.

The person who wrote this docket could very well remember the days that most ships went by sail, not steam. They might even have experienced a time when you would WANT to indicate on a letter that you wanted it to go by a steamship rather than sail.

Perhaps I should have included option 4: Old habits die hard.

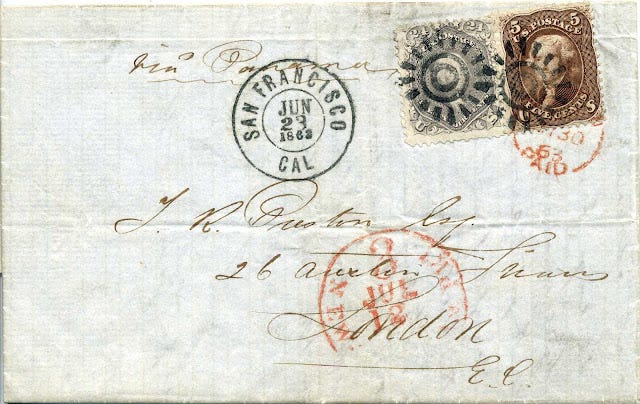

The item below, shows some successful direction given by a docket:

The words "via Panama" very clearly directed the post office in San Francisco to put it on a steamer that would go down the Pacific coast to Panama. The letter then would go overland at the isthmus and then board another steamer to New York from the eastern shore of the isthmus.

In this case, there were a couple of routing alternatives. The default route was for letter mail to go overland in 1863 since overland routes were in use at that time from California. So, if a letter writer preferred the steamship via Panama, they had to indicate that preference as this person did here.

The question is, of course, "why did this person want this to go on the slower route?" We may never know this answer for certain. But, perhaps the sender had heard enough about mail coach robberies that they did not want to risk that with this mail item? Maybe there was a known weather issue that was going to delay overland mail? Or perhaps, they were aware of uncertainties with respect to conflict with Native Americans along the mail route?

The Bear River Massacre in January of 1863 led to tensions that impacted the mail route near Salt Lake City. An incident involving US soldiers harassing Native American women and injuring members of the Goshute led to a conflict. The Goshute, after being defeated swore revenge on the bluecoats (referring to the soldier's uniforms). Unfortunately, they identified mail coach drivers as bluecoats and killed both men on a mail coach early on June 10th of the same year - just a couple weeks before this letter was mailed.

However, other than a short period in 1862, overland mails were not halted due to conflict. They might be delayed at point along the route if sections were impassible for a time. So, it was entirely up to the sender to decide if they wanted to apply a docket telling the US Post Office to take the route via Panama.

Whatever the case, this is a time when the directive was followed - even if it was going to result in slower transit of the mail item.

And here is another successful routing docket. This one reads "by the Persia Aug 24 in New York."

Unfortunately for the postal historian (me), there are no contents in the letter and there is no originating postmark, so I cannot tell for certain where this item was mailed from in the United States. Clearly, it DID go through New York and it DID leave on a ship from New York on August 24 (yes, it was the Persia). So, you could say that the docket worked - it went where the writer wanted it to go based on that agreement.

But that raises a question - was that docket really necessary?

Did They Need Dockets by the 1860s?

By the time we get to letters in the 1860s, the need for writers to include directional docketing had been greatly reduced - though there were times when it was still necessary. As far as mail from the United States to England, the postal service had a pretty good system for getting letters to the earliest departing steamship or identifying the quickest route - there was very little a directional docket would do that would improve that.

As long as the letter above was mailed on time for that New York departure, it was probably going to take the earliest departing ship (the Persia) even without the docket.

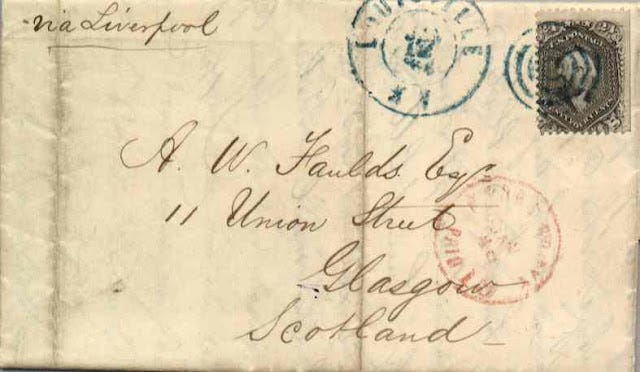

So, does the letter below actually has a somewhat useful docket?

The docket "via Liverpool" could be construed as a directive to put the letter on one of the shipping lines that went through Liverpool - but it actually did more than that. You see, the Cunard Line of ships would stop at Cork, Ireland, and offload mail for England there. That mail would then go by rail, cross the water from Kingston to Holyhead, and then on to London by rail.

Because this item was headed to Scotland, the writer indicated that it should stay on the ship until it got to Liverpool the next day. From there it would go to Glasgow.

But, again, there is a question as to exactly how useful the docket might be because the mail volume to the United Kingdom was sufficient that mail to Scotland could have been placed into its own mailbag. If that were the case, it would take the most efficient route to Scotland without needing the docket.

Once more, this is a case where we see mail handling in the process of change. Dockets that were once critical in directing the mail were becoming less important as the amount of mail increased, available transportation options changed, and the mail sorting and routing procedures became more refined.

Back to the Original Cover

Here we are - back at the original item with the docket claiming the letter should go to Boston and leave on the Cunard Steamer Asia on April 25 (Wednesday). But, clearly, it left New York on a steamer that Saturday (April 28).

The reason for the delay is simple. The writer did not make it to the post office in time to get the mail to Boston and the departure of the Asia. The post office simply sent the item to New York, where the next ship was scheduled to sail across the Atlantic.

But, here is the problem for the post office. The writer makes a claim by saying the letter was to leave Boston on April 25. Postal services around the world had to frequently deal the pressure of timely carriage of the mail - and people weren’t bashful about complaining when their mail was delayed. If they just let the docket stand as evidence for when the letter was mailed, the recipient just might feel obliged to express some unhappiness.

The post office provided themselves an opportunity to make it clear that it was not THEIR problem by putting a "Too Late" marking on the envelope.

"Hey, George Atkinson. I don't care what the guy who wrote this says - he didn't get it to us in time for that ship. Take it up with him!"

This illustrates a bit more about why dockets were still routinely placed on letters. It could often serve as attempt to provide evidence of timeliness during an era when it took eight to twelve days to cross the Atlantic - and a missed ship could add three more days to the wait!

Bonus Docket Fun!

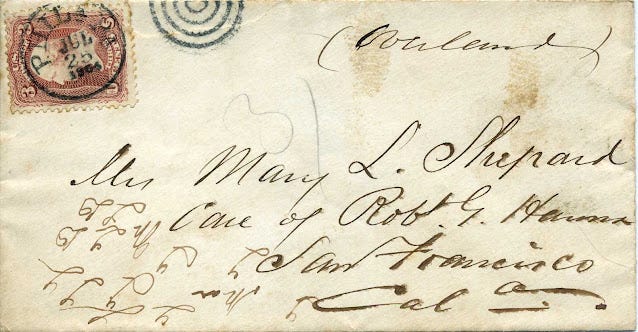

I thought it might be interesting show a docket that was placed on an envelope that instructed a letter to take the overland route to California. Unlike the prior example, this envelope was traveling from the East Coast to the West Coast.

Yes... that says "overland." I recognize that handwriting can be difficult to decipher sometimes, even if you know cursive. I have to admit that it helps if you know what sorts of words are likely to be put on an envelope for a docket. For example, letters traveling across the United States are likely to have dockets that say "overland," "steamer," or "Panama" if there is going to be a directional docket during the 1860s.

This triple weight letter, with nine cents in postage, also has a docket on the right hand side of the envelope. It is oriented so it reads sideways, which is often a signal to me that this is probably a docket applied by the recipient for filing. Of course, this is not always true, but it is a rule of thumb that has seemed to make sense for material during this time period.

If it is a filing docket, you can often expect names, dates and place names. Frequently, there might be reference to legal materials that were likely contents or were referenced by the contents that were inside the letter. This time, I believe the docket reads "vouchers." Of course, if someone sees it differently, feel fee to disagree!

I think I will close with a favorite docket of mine. In this case, we could argue that this is not so much a docket as it is part of the address. Frankly, I wouldn't be upset if you wanted to describe it either way because our need to call it a docket is secondary.

This letter was mailed from Grand Rapids to Galesburgh, Michigan in Kalamazoo County. The addressee actually lived closer to a small town outside of Galesburgh. The docket reads "Please forward to Climax with Daily Mail." You can learn more about this particular item in a Postal History Sunday titled The Rural Burden, if you have interest.

I hope you enjoyed today's entry. Have a great remainder day and a fine week to come.

Additional Reading

I have heard from some people that one Postal History Sunday isn’t enough on some weekends. So, here are links to other PHS that are related to today’s topic.

The Rural Burden - PHS #74

Correspondence Course - PHS #73

Crossing the Pond and Lighting a Candle - PHS #134

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. Some Postal History Sunday publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.