That Doesn't Seem Fair - Postal History Sunday

Welcome again (or maybe for the first time) to Postal History Sunday! Take a moment of time to read about something different and maybe learn something new. Stuff those worries in the cookie jar for a little bit and make sure you take some cookies out to enjoy while you read.

This week I am going to write about a topic that I often find myself explaining to other postal historians who do not share my specific area of interest. Now, before you think this will be 'too much,' I can assure you that if you have read any of the other Postal History Sunday posts, this one won't get any more into the weeds than those. You're going to do just fine.

Now, if you're worried because you ARE a postal historian and you think this will be boring because it will be too simple... I guess that's your call! But, I bet I can find something interesting for you before we reach the end.

This week's "attention getter"

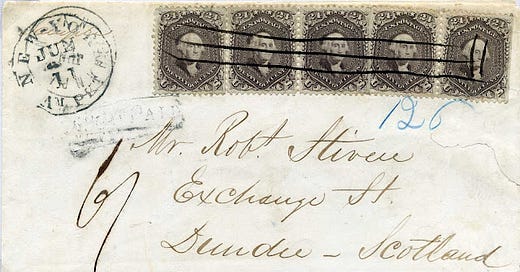

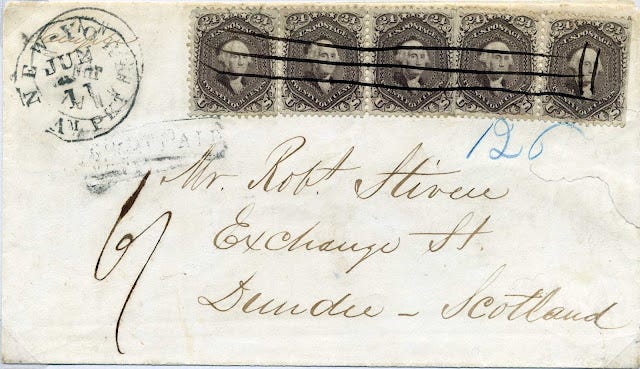

I'm just going to put this envelope right at the top of the blog. For those of you who are into postal history or philately, you probably already have some level of appreciation for this item. And, if you don't know anything about postal history, let me point out to you that there are FIVE twenty-four cent stamps on this letter paying $1.20 in postage.

The letter shown above was mailed in 1864 from Champlain, NY, to Dundee, Scotland. The cost at the time was 24 cents for a simple letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. OR, if it weighed more than a half ounce, the cost was 48 cents per ounce. So, this letter must have had some weight to it.

But that's not the big reason this envelope is interesting to me. You see, this letter did not have enough postage to pay what was owed. The agreement between the US and the United Kingdom was written in such a way that if something was not fully prepaid, it was treated as if it was not paid at all. As a result, the recipient had to pay the full postage due (6 shillings) and the $1.20 essentially became a gift to the US Post Office.

How could that possibly happen? That's what today's Postal History Sunday is all about!

Sending a letter to England

This next envelope was mailed in 1862 from Boston to London, England. This was a simple letter, meaning it did not weigh more than the amount allowed for the first increment of weight (1/2 ounce). As we would expect, there is a single 24-cent stamp paying that postage.

Today, in the United States, it costs 63 cents to mail a letter that weighs no more than one ounce in weight. It costs $1.45 to mail a simple letter (a letter that weighs no more than one ounce) to Scotland in today's mail. So, if you're thinking, "Wow. It sure does seem like it cost a fair bit to send a letter to England in 1862." You would be correct.

In fact, the letter rate actually decreased to 12 cents in 1868 and was reduced further to six cents not long after. By the time we get to the days of the General Postal Union (1875), that price was 5 cents!

To make the point that postage rates declined rapidly after the 1860s, shown above is a simple letter that was mailed from Utica, New York, to Huddersfield, England. The postage stamp covered the cost of postage - two cents - in 1916.

As one of my college math professors was fond of saying.... "But, I digress...."

Getting back to the 1860s. The twenty-four cents of postage was split into three pieces:

5 cents was kept by the United States for their internal mail service

16 cents were paid to the sailing company that carried the letter across the Atlantic

3 cents were kept by the British for their internal mail service.

The wild card here was that some sailing companies had contracts with the British and some had contracts with the U.S. It actually mattered which ship carried this letter because it determined which mail service got 16 cents worth of the postage so they could pay the shipping line.

The US Post Office sold the stamp for 24 cents to the customer, who put it on the envelope to show that they had paid for the service. This letter went via a British packet (steamship), which means the British needed 19 cents (16 + 3) to pay for their part of the services needed to get the mail to the Reverend A.P. Putnam in London. If you look at the Boston postal marking, you can see "19 Paid" which recognized that 19 cents were to be passed on to the British postal services.

What if it weighed more than a half ounce?

Well, 24 cents would not cover the cost of mailing that item - of course!

remember, you can click on an image to see a larger version

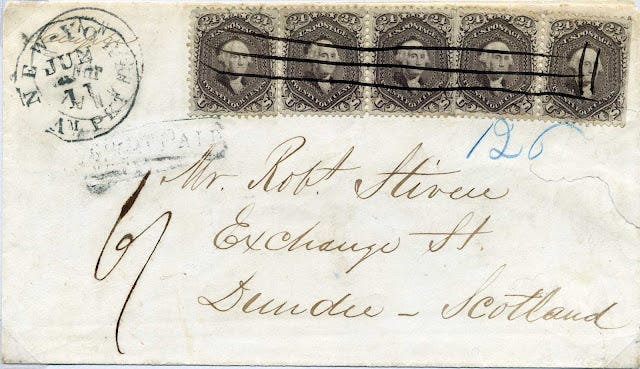

Here is a larger envelope that must have been more than a half ounce, but no more than one ounce in weight. It was mailed from Chicago to Shaftsbury, England. Two, 24-cent stamps were placed on the envelope to pay 48 cents in postage. This letter was sent via a steamship that had a contract with the United States, so only 6 cents was passed to the British. If you look at the left side of the envelope, you can see a red marking that reads "6 cents" with the word "cents" in an arc below the number.

Below is a summary of the rate table for mail from the US to the United Kingdom from 1849 through 1867.

You might notice that the rate of postage was not 24 cents per 1/2 ounce. It might be better to think of the 24 cent rate as a special rate for very light mail. The actual rate might more accurately be said to be 48 cents per ounce.

But, wait a minute - did I say that the letter above was mailed from Chicago? How did I know that? The clue lies with that "6 cents" marking I was talking about earlier.

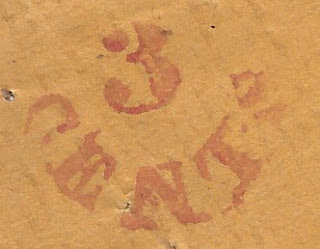

One of the magic powers postal historians develop over time is the ability to recognize certain markings and understand where they came from. The "6 Cents" marking was used in Chicago to show that the British got 6 cents out of the 48 cents in postage. There is a similar, more commonly found "3 Cents" marking used for letters that were a half-ounce or less in weight.

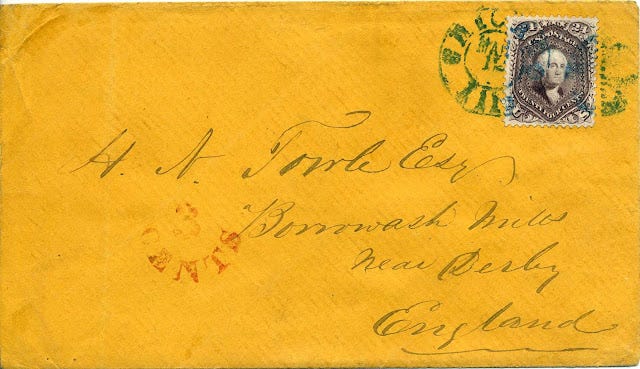

Here is an example of a simple letter that was mailed from Chicago. The blue postmark at the top rigth reads "Chicago, Ills" and we can see a "3 cents" marking that looks a lot like the "6 cent" mark on the other envelope. Shown below is another example blown up so you can see the details.

Letters that went through the Chicago exchange office in the 1860s were typically sent to either Quebec or Portland, Maine so they could get aboard an Allan Line ship. The Allan Line had a contract to carry mail with the United States, so the British only got 3 cents and the United States kept 19 cents so they could use 16 cents to pay the cost of trans-Atlantic carriage.

But, what if they didn't pay enough?

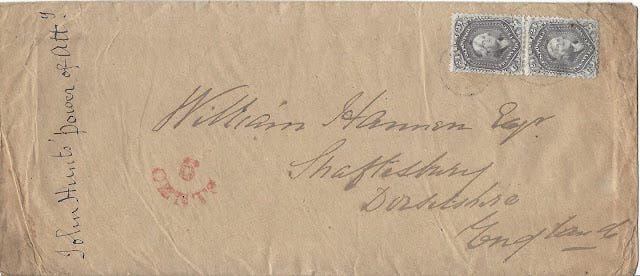

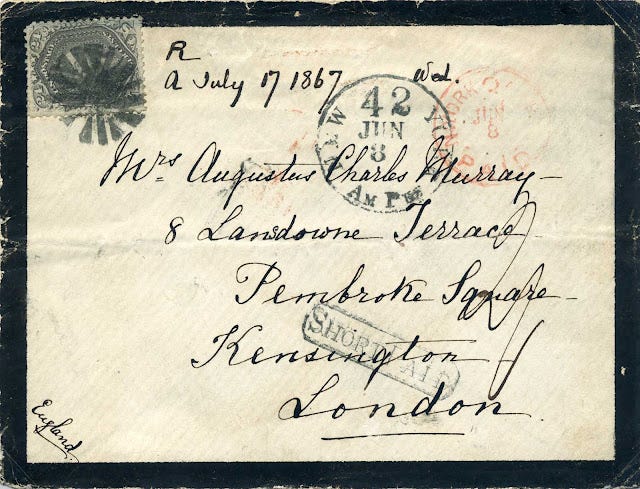

People didn't always get the postage right - so there had to be some sort of an agreement to determine how "short paid" letters would be handled. For example, the letter below (from 1867) has a single 24 cent stamp on it - but it must have weighed more than a half ounce, so it needed 48 cents in postage.

The New York foreign mail exchange office placed a "Short Paid" marking on the envelope and used black ink for their circular marking (the one that has a "42" in it). The interesting thing is that this letter must have caused the postmaster some trouble because there is a red marking just to the right of it that indicated it was paid.

You can guess how that might happen. The clerk was going through a pile of letters, stamping them with the red paid marking and got into the rhythm of the work. He hit this one with the handstamp and then said "hmmmmm." Weighed it out and realized his instincts were correct - so he put the "short paid" and the black circular marking on the envelope.

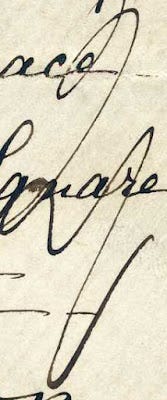

The British Post Office agreed with this assessment and wrote the squiggle on the envelope that is a 2 with a squiggly tail. This was their way of saying the recipient owed 2 shillings for the privilege of receiving this letter. The envelope contained a death announcement, which is indicated by the black border. I have a suspicion most people would have found a way to pay the 2 shillings in this case.

How much was 2 shillings in US money? 48 cents.

The agreement between the United States and the British at this time was that a letter that was not paid in full would be treated as COMPLETELY UNPAID. Well, that's one way to make a death announcement sting a bit more. The sender spent 24 cents to send it and the recipient had to pay the equivalent of 48 cents to receive it. Ugh!

It could be worse!

The letter below has 72 cents in postage applied to it AND the recipient had to pay 4 shillings (equal to 96 cents) to receive it.

This larger envelope must have weighed more than one ounce, so it would require more postage. So, let's remind ourselves of the postal agreement rates:

Oh... yeah. It isn't 24 cents per 1/2 ounce - it's 48 cents per ounce once you get to things heavier than a half ounce. But, that's not what everyone understood when they mailed things. After all, if you wanted to send a letter inside of the United States it was 3 cents for EVERY 1/2 ounce. It would be natural to expect a rate to a foreign country to follow the same pattern - and that's what the sender of this envelope expected when they put three 24-cent postage stamps on this large envelope.

The letter must have weighed over one ounce and up to 1 1/2 ounces. They figured 72 cents was correct if you had 24 cents per 1/2 ounce. But, they were wrong - which means the letter was Short Paid. Which means it is treated as UNpaid.

Ugh again!

Oh my goodness!

And all of that brings us back to our original item. If you thought the prior letter recipient was being treated poorly, what about poor Mr. Robert Stiver of Dundee, Scotland? He had to pay 6 shillings for this item sent in the mail to him.

You can guess what happened here. The sender expected that five 24 cent stamps would pay for a letter that weighed no more than five 1/2 ounce increments. In other words, the letter weighed over 2 ounces but not more than 2 1/2 ounces, so they figured it should require 5 times the 24 cent rate per half ounce.

Sadly, the rate REALLY WAS 48 cents per ounce, despite what the general public might think. The letter weighed more than 2 ounces and no more than three ounces - so it needed $1.44 instead of the $1.20 affixed to the envelope.

The clerk in the New York exchange office, recognized that this was not enough postage and they struck this letter (badly) with a "short paid" marking to alert the receive exchange office in Scotland. Perhaps a good way to think of this is to consider that the outside surfaces of a mailed letter could be used so postal clerks could send messages to their counterparts at future stops.

But, not every marking was perfectly clear - just like some people's handwriting can be nearly impossible to read. That's why there were regulations that included directives for ink colors. The color red typically indicated that a letter was prepaid and black would be an alert that postage would be due.

The New York exchange office marking was applied in black, which also told clerks who would handle this letter later that it was NOT considered paid, despite the postage stamps clearly visible on the envelope. It is a bit difficult to read because it was placed over the Champlain, New York postmark.

But, this leaves us with the issue of how much of the postage goes to the United States and how much goes to the United Kingdom! That's where this number comes in:

This number was supplied by the New York exchange office and it represents 126 cents (or $1.26). In other words, the United States expected that, once the letter was delivered in Scotland, the postal carrier would collect six shillings (equal to $1.44). The British post would keep only 18 cents (9 pence) and it would send the rest (5 shillings and 3 pence) to the United States.

From the United States Post Office's perspective, they did pretty well with this letter. Someone had already paid them for the $1.20 in postage stamps, but none of that postage effectively paid for any services. Then, the US Post Office received an additional $1.26 from the British to pay for the services the US provided.

If you don't think that seems fair, consider how Mr. Stiver must have felt when the postal carrier pointed at this marking on the envelope:

That's squiggle represented 6 shillings due.

I sure hope the content of this envelope was worth every penny!

How or why could they do this?

It would be tempting to leave you thinking that the postal services were deliberately stealing money from postal patrons with this process. But, that's not exactly what was going on here. Postal services around the world were still trying to get people to move from a system where postage was collected on delivery to one that had services prepaid by the sender. One of the best ways to do this was to make people pay more when they failed to prepay.

The prior system, where letters were paid at delivery, opened the door for postal services to carry mail all the way to their destination only to have the recipient decline to pay. Of course, the letter would not be delivered in that case. But the post had done all the work and gotten no compensation for it.

Relief!

We will close with a letter that was mailed from Boston to London in June of 1866. There are three 24-cent stamps paying 72 cents in postage. But, this letter has red exchange markings and the word "Paid" shows prominently in the messages mail clerks were sending to each other on the envelope.

If we learned anything from all of the prior items I've shown, it was that an odd number of 24-cent stamps (other than a single stamp) was going to result in some unhappy recipients as they ended up paying the full postage just to open the letter.

On April 1, 1866, the postal rate from the US to the United Kingdom was altered so that it would be 24 cents PER 1/2 ounce. Suddenly, these odd multiples that the public seemed to think should be allowed WERE allowed. It only took 17 years (the treaty became effective in 1849), but some relief was granted to those who were honestly trying to pay the postage yet fell prey to a bad assumption.

The postage rate itself would decline to 12 cents per 1/2 ounce on January 1, 1868. So, these odd multiples of 24 cent stamps that were accepted as paid are difficult to find. Once you put this envelope together with the other items in this Postal History Sunday, it makes a pretty good story.

Thanks for joining me. I am hopeful that you learned something new! Have a great remainder of the weekend and a good week to come.

-----------

Postal History Sunday is published each week at both the Genuine Faux Farm blog and the GFF Postal History blog. If you are interested in prior entries, you can view them, starting with the most recent, at this location.