The Case of the Doanwanna

Postal History Sunday #218

I had a recent conversation with a friend who was talking about different personality types and traits. I am guessing that many of you who are reading Postal History Sunday have at least some experience with the Myers-Briggs tests and maybe other tests that can be used to give insight into a person’s preferences and tendencies. Some of the tests out there are questionable and, in my mind, they become more questionable when they work hard to make money off of the product. But, if you have the right frame of mind and are willing to take your learning in whatever way it presents itself, you can usually get something out of them - even if it is a good laugh.

My friend noted a category for motivation that applied to both of us. The description was “no one can make me do it, including myself!”

All we could do was laugh about it - because we both knew it applied equally well to each of us.

And that’s where I found myself this week when it came to Postal History Sunday. I was rebelling against my own authority that was telling me I needed to write.

I decided it was the case of the Doanwanna. I doanwanna write Postal History Sunday.

Doanwannas struggle in the face of interesting things

Well, if I am going to be the person that gets in my way the most when it comes to writing, perhaps I can convince myself to write by looking at something a bit different from what I normally work with?

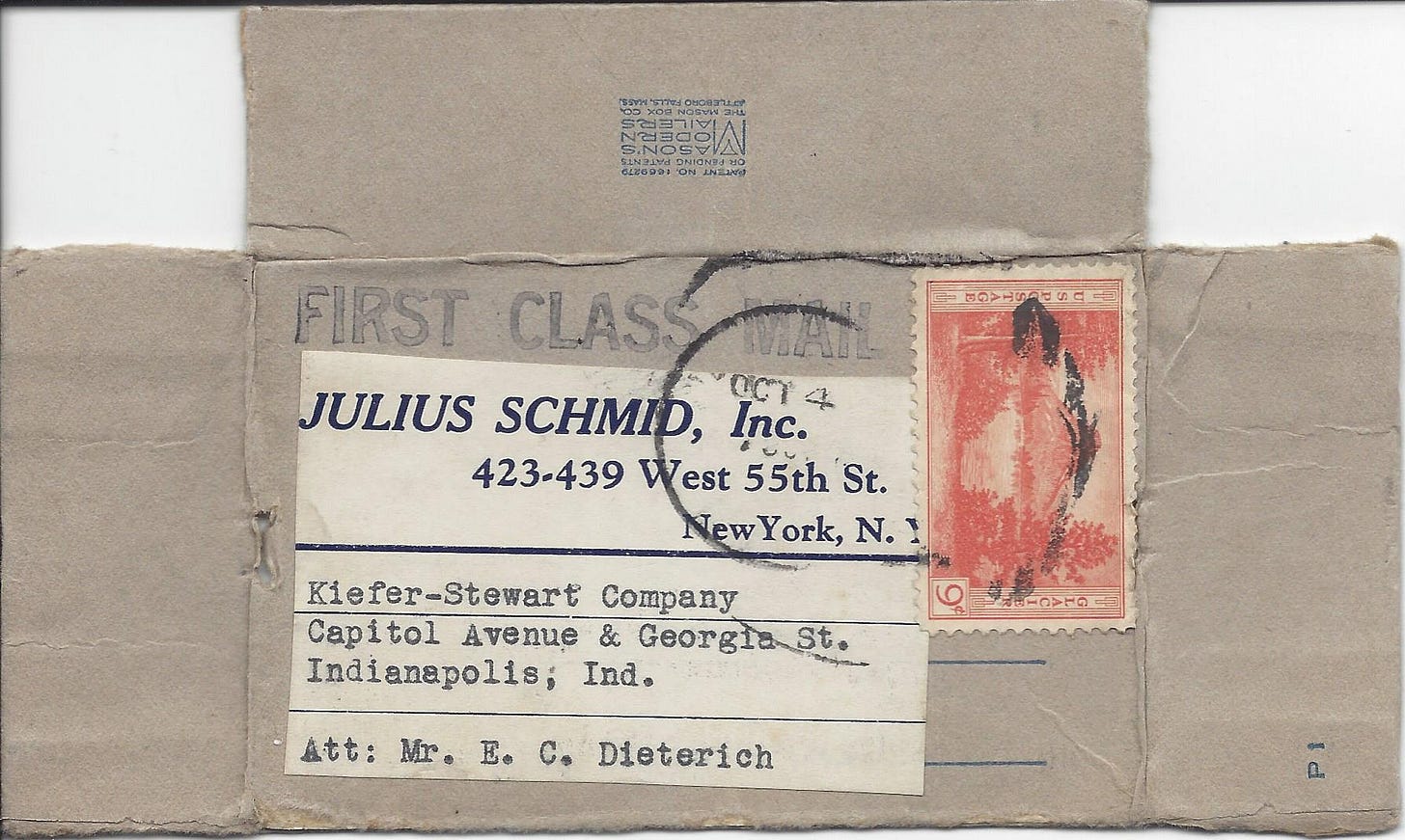

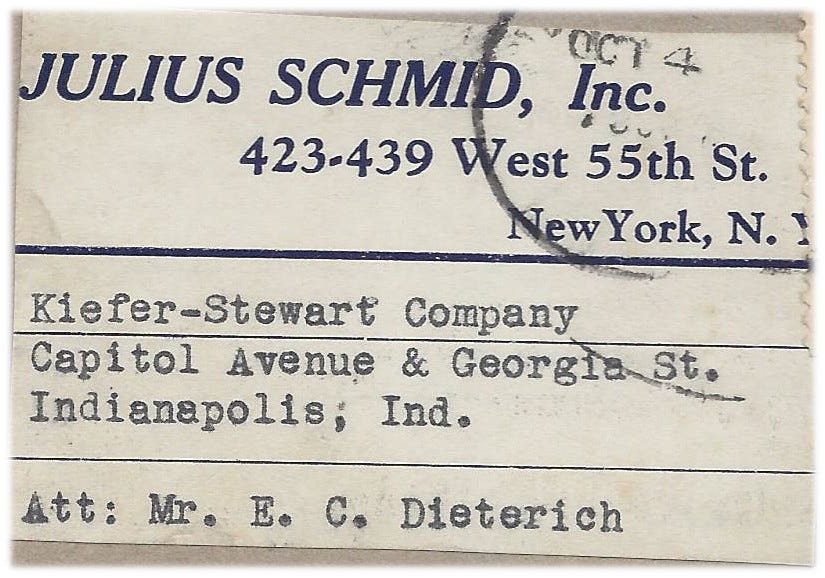

Our feature item this week is a flattened box top that has one flap, or side, missing. The bottom portion of the box did not come with the top and there are no contents. You can get a sense for size by looking at the postage stamp itself. If that doesn’t work, the box would sit easily in my hand. For those who might have played a string instrument, like a cello or violin, the box is similar in size to the boxes that held rosin for bows. The depth is just about perfect, but the width and length is a little large for the rectangular rosin cakes I have used.

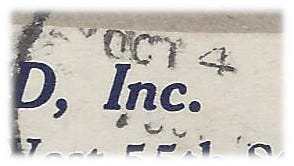

The postmark (the round marking in black ink) tells us it was mailed on October 4, but the year did not imprint completely on the box. With imagination and some additional knowledge we can deduce that it was likely mailed in the 1930s.

The 9-cent postage stamp features Mount Rockwell and Two Medicine Lake at Glacier National Park in Montana. It was part of a set of stamps issued in 1934 featuring various US National Parks. The 9-cent stamp was first released on August 27, so we know the earliest date this item could have been mailed was October 4, 1934.

If we blow up the image, we can only see the bottoms of the numbers for the year date. However, the rounded third number supports the likelihood that it is a “3” and the single, vertical straight line leads me to believe it is either a “4” or “7,” both of which are quite possible.

If we can agree that this was mailed in 1934 or 1937, we can try to deduce the reason for 9 cents in postage. There is a handstamp marking that reads “First Class Mail,” which tells me the sender intended that it would be subject to the standard letter rate of the time. Typically, I would expect items containing merchandise to be mailed as Fourth Class Mail - or Parcel Post. So, we might have a bit of a quandary.

If the letter was sent under the First Class letter, the rate of 3 cents per ounce applied (July 1932 until 1954). Even though the First Class letter rate was intended for printed content, it could also apply to other content that was sealed and not easily inspected by the postal clerks. If that was the case, this little box, along with its contents weighed more than 2 ounces and no more than 3 ounces in weight. For reference, a cake of cello rosin might weigh between 1 and 2 ounces.

And for those of you who think I might be foreshadowing - beware of red herrings!

If this were sent via Parcel Post, the postage required would have been 11 cents (for a package weighing less than a pound, but more than four ounces. If it weighed less than four ounces, it would have cost 1 cent per ounce - giving us a maximum cost of 4 cents in postage. It appears the reasonable explanation is that it was sent as First Class mail as a triple weight letter for a cost of 9 cents.

Of course, if someone who has more experience with rates during this period than I do has a different explanation, I am willing to hear it! But for now, I’ll stick with this one.

Could this box carry a Doanwanna?

This little box had a patent (No. 1669279) that would have been issued in the late 1920s, so I decided to take some time and try to hunt it down. Happily, Hathi Trust houses scanned volumes of the Index of Patents Issued by the US Patent Office for 1928 and I was able to find the listing for this box.

Apparently the fastener that kept the box closed while it was being transported by the US Post Office was the part of the box that had been patented. And since I have the patent number, I could go to the USPTO’s basic search tool and see if there was a document with the patent submission.

The patent was for the attachment of a “ductile wire” to the box’s base. Slots were cut into the box top. When the box top was placed onto the box base, the wire loops would go through the slits on the box lid. To secure the package, the wires were then bent down so they were flush with the box lid. To open, a person would unbend the loops and lift the lid off of the box base. If you look again at the image of our box lid, you can most easily see one of these slits at the left.

This is also interesting to me because I recall getting boxes of cello rosin (I forget which brand it was) with a similar fastening mechanism.

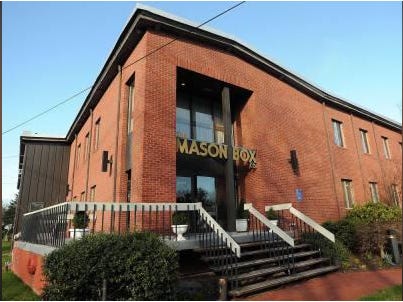

The Mason Box Company is now a subdivision of Interpak, an international concern, but according to a business history published in 1930*, the Mason Box Company consisted of two factories and a corporate office in New York City during the decade this item was mailed. The main factory was located in North Attleboro, while the second was in Providence, Rhode Island.

At the end of the 1920s, the Mason Box Company offered a “complete line of boxes of all kinds and display cases… [there was] a leather novelty department, a complete printing plant, and a steel die printing department.” But, the company specialized in containers for mail shipments - just like this small box.

The Mason Box Company had a modest start in 1891 when J.F. and C.O. Mason began to manufacture small boxes for the jewelry trade that was prominent in the area. They worked in a small building behind their home and employed a few women to help with making the boxes.

Some of you might have noticed that the address printed on the box was for Attleboro Falls and not North Attleboro. Attleboro Falls is now a neighborhood in the larger North Attleboro community.

*History of Massachusett Industries Their Inception, Growth and Success, Orra L. Stone, S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 4 volumes, 1930. The portion cited can be found online here.

No more Doanwanna - I wanna know what was in the box!

When I am presented with a piece of postal history that provides very clear clues with the respect to the recipient AND the sender, it’s a bit like a big blinking sign that says “YOU MUST LEARN MORE!”

I started by searching out the Kiefer-Stewart company, which was a wholesale drug firm. The result of a merger of two other firms in 1915, I suspect you would not be surprised to hear that one was the A. Kiefer Drug Company and the other was the Daniel Stewart Company. Nothing like creativity in naming - at least not around here!

The company operated from this location at Capitol and Georgia Streets until 1965. Its customers were located in Indiana, Ohio and Illinois. In addition to the wholesale drug business, there was a liquor and wine department. This brings up an interesting question that has to do with Prohibition (18th Amendment), which ran from 1920 to December 5, 1933 (there was some beer and wine production allowed after an alteration to the rules in March of 1933). Was Kiefer-Stewart involved in the alcohol business during this time period?

And the answer is… yes.

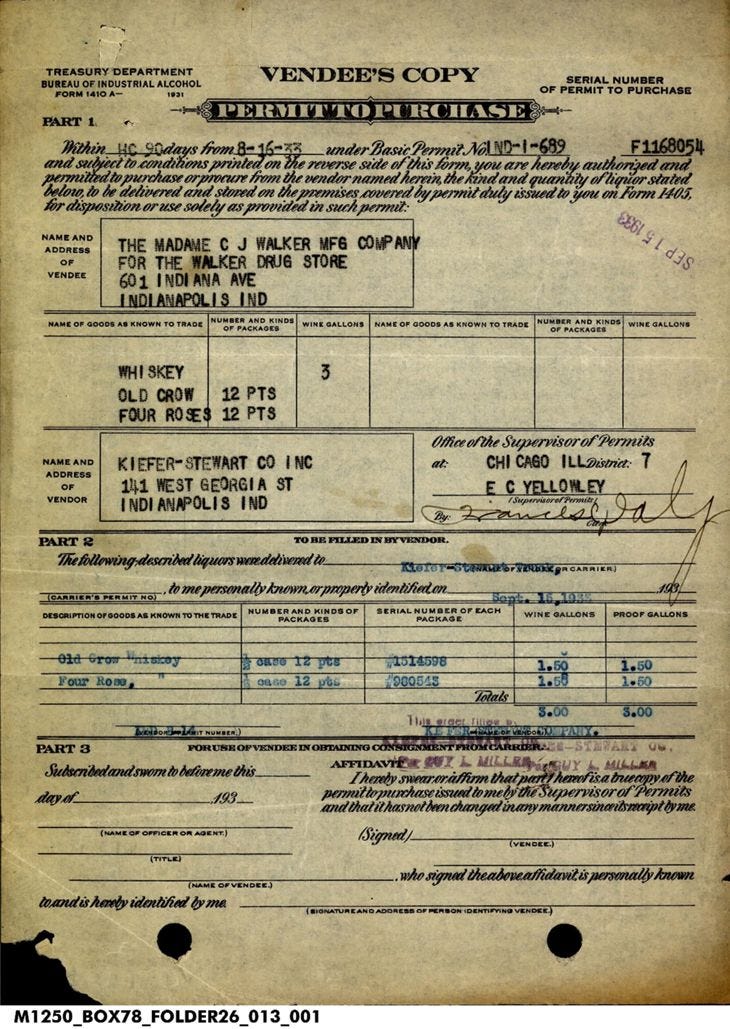

Shown above is a permit dated August of 1933 allowing the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company to purchase alcohol from the Kiefer-Stewart Company. The form is a Permit to Purchase issued by the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Industrial Alcohol. The Treasury Department was charged with overseeing a wide range of permits, while also attempting to enforce the rules set forth by the Volstead Act - which attempted to outline how the 18th Amendment would be put into action.

While the sale of alcohol as an intoxicating beverage was not allowed, it could be used for other purposes. The permit I show above was intended to allow the purchase of alcohol for purposes OTHER THAN beverage purposes from Kiefer-Stewart. It seems clear to me that Kiefer-Stewart was able to maintain permission to sell alcohol during the Prohibition period, most likely as an ingredient for medicinal purposes.

At this point, you might be wondering if I was going to tell you that this box held a very small bottle of alcohol and not cello rosin. The answer is that it most likely did not hold either of these things. But, it does set a precedent that the Kiefer-Stewart Company, as a wholesaler, did not seem to have a problem with selling things that might not be embraced by the whole population and that might even have restrictions on how sales could proceed.

All of this brings us to the company that sent the box, Julius Schmid, Inc.

Julius Schmid emigrated from Germany in 1882 and, after a rough start in the United States, worked for a sausage-casing manufacturer. He soon developed a side business creating condoms using the same skins that were used for sausage casings. Schmid, however, had a significant hurdle to clear - selling condoms was illegal in the United States at that time.

The Comstock Act, part of a broader bill focused on the workings of the US Post Office, passed in 1872. The act defined contraceptives as obscene and outlawed their dissemination through the mail or across state lines. Some states followed with even stricter measures. In Connecticut, the act of using birth control was prohibited by law. Enforcement of those laws was another matter, of course. Many officials were unwilling to get involved in private affairs - especially those between married couples. And, the feeling that people had the right to engage in family planning and manage their reproductive health was growing.

Schmid’s home was raided in 1890 and he was found guilty of selling articles to prevent conception. He was made to pay a $50 fine and was released on $500 bail. However, work as a condom bootlegger was lucrative enough that he paid what was required and went on with his business.

Schmid and his company were very adept at adjusting to sell their product within the letter of the law. Early on they advertised their products as “French goods and medicines.” When the rules were changed to allow the use of condoms to prevent disease, the company made sure to sell products through drug stores. Their labeling clearly stated that these condoms were sold “only for protection against disease.”

By the time this box was sent from Schmid’s company to the Kiefer-Stewart Company, the legal status of condoms had changed. Birth-control advocate Margaret Sanger was arrested in 1916 for opening a birth-control clinic and the resulting court decision (1918) allowed women to use birth control for disease prevention. This was followed by a 1936 US Circuit Court of Appeals decision (US v. One Package) that made it possible for doctors to distribute contraceptives across state lines.

Schmid’s products were more expensive than other, similar products, but they were considered to be more reliable and of better quality. The US Military even asked Julius Schmid Inc to supply condoms during World War II.

So, this brings us to the conclusion. This box held packages of condoms. Not rosin for cello bows. Not a small bottle of alcohol. One single box seems to be fairly minimal for a wholesaler, so maybe E.C. Dieterich was using his position with Kiefer-Stewart to acquire what he wanted? That’s something I’ll never know.

However, it does seem that a weight of 2 to 3 ounces would not be far off for this package if it were filled with packages of condoms. Perhaps Shmid used First Class mail because it allowed the mailing of sealed contents that were not typically going to be inspected by a clerk to see if it qualified for a cheaper postage rate.

I can’t be completely sure of that answer either, but I did get rid of the case of the Doanwanna.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

Another interesting glimpse into the history of America, at this interesting intersection in American history. How does that old saying go? "The more things change, the more they stay the same."

Reminds me of another Gerald Weinberg quote a friend sent me recently - "Systems tend to maintain the status quo, long after the quo has lost its status."