The Difference A Day Makes

Postal History #205

Welcome to Postal History Sunday!

Before we get started, we should take care of our housekeeping. First, I would like to remind everyone that these articles are written to be accessible to those who know little or nothing about postal history while still providing interest to those who might be considered experts in the topic. Hopefully, I will achieve this in a way that is both entertaining and (uh oh) educational. Maybe you’ll be enjoying yourself so much that you won’t realize you just learned something new!

So, let’s all take those troubles and worries and send them outside to amuse themselves. Pour yourself your favorite beverage and maybe even treat yourself to a snack. Put on the fuzzy slippers, sink into your favorite chair and enjoy the read.

As a person who enjoys both postal history and learning, I am especially appreciative when I can find covers that help illustrate a specific concept or situation. I enjoy it even more when I can find a pair or set of covers that illustrate a changes in the mail system. Today, I am going to share a couple instances where I have been fortunate enough to do just that.

April 1, 1866: No More Being Fooled By a Postage Rate

I am going to start with an envelope that was mailed in 1866 in Newark, New Jersey that was intended for a recipient in London, England. There are five 24-cent postage stamps along the top of the envelope to pay $1.20 postage. And, apparently, that was the correct amount to pay because all indications on the envelope tell me that this was treated as a fully prepaid piece of letter mail.

There are two circular postmarks in the center of the cover applied in red ink that include the word “paid.” So, in a very real way, there isn’t much of a mystery here as to how I was fairly certain that the letter was properly paid. I just exercised my ability to read faint or partially struck postal markings. But, there are other pieces of evidence that help me confirm that those markings are correct.

First, the postage rate for letter mail from the US to the UK at the time this letter was mailed (September 16, 1866) was 24 cents per 1/2 ounce of weight. So, it bodes well that 24-cent stamps were used to pay the postage. Since there are five stamps here, this would be a letter that weighed no more than 2 1/2 ounces, but more than 2 ounces. This postage rate became effective on April 1, 1866 and continued until December of 1867 when the postage rate was reduced to 12 cents. (I thought it might be refreshing to mention postage rates going down in today’s PHS!)

The second piece of evidence is the number “"95” written in pen at the top left. This represented the amount of postage that was due to be sent to the United Kingdom to cover their portion of the expenses. For each half-ounce, the British Post was owed 3 cents per 1/2 ounce for their internal mail services. And, since the Scotia carried this letter across the Atlantic and was under contract with the British, they also received the 16 cents per 1/2 ounce needed to pay for the trip across “the Pond.”

If you don’t like math, I’ll do it for you.

3 + 16 = 19

(3 cents British internal mail + 16 cents for the ship to cross the Atlantic)

19 x 5 = 95

(19 cents due to the British per 24 cent rate x a letter that weighed enough to require 5 such rates)

Everything here checks out that this is a properly paid letter that weighed over 2 ounces and no more than 2.5 ounces that was mailed under the April 1, 1866 postage rates. By itself, I think that’s pretty neat because it is much harder to find old pieces of mail that carried heavier content. Most surviving covers are simple letters (weighed no more than 1/2 ounce). But, it gets even neater after I show you this cover too!

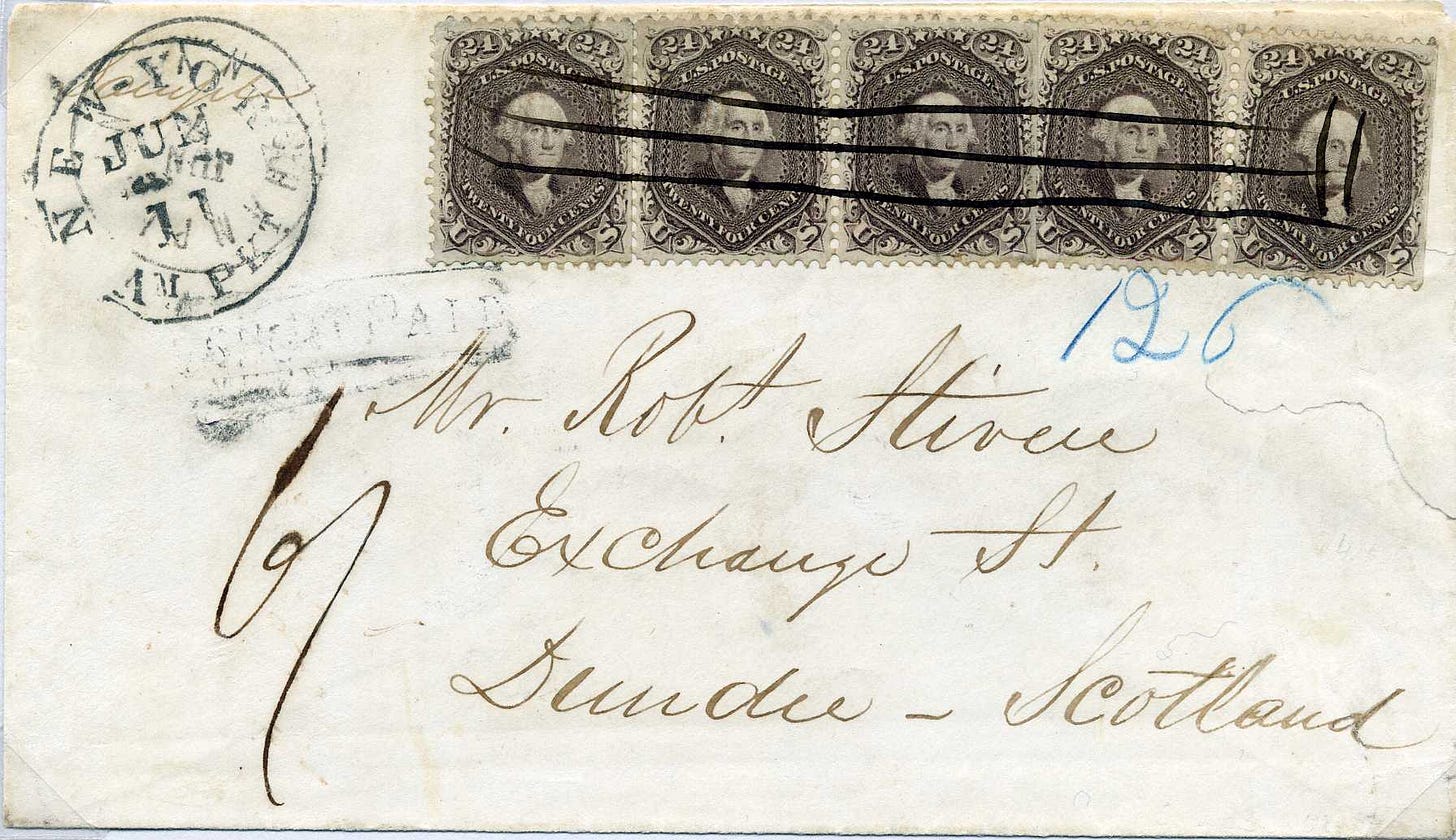

Here is another envelope that has five 24-cent stamps across the top. But, I’ll cut right to the chase and tell you that it WAS NOT properly paid and the recipient was required to pay the full postage (6 shillings) when it was delivered to them. The postage stamps ended up paying for …. nothing!

The letter shown above was mailed in 1864 from Champlain, NY, to Dundee, Scotland. In other words, it was mailed before our magical April 1, 1866 date. The cost of postage in 1864 was 24 cents for a simple letter that weighed no more than 1/2 ounce. If that letter weighed more than a half ounce, the cost was 48 cents per ounce.

It is very likely that the sender of this letter knew that it weighed over 2 ounces and no more than 2 1/2 ounces (just like our last example). Since US postage rates followed a linear progression (3 cents PER 1/2 ounce) they probably assumed the same thing for mail from the US to the UK also applied. They dutifully multiplied 24 cents times 5 and got to $1.20 - which was plenty of money in 1864. They paid for the stamps. They put them on the envelope and they mailed it.

And the post office immediately recognized that this letter was a triple weight letter for the 48 cent rate. They saw it as a letter that was more than 2 ounces in weight and no more than 3 ounces total. So, the cost should have been 48 x 3 or $1.44!

So, the New York Foreign Mail office clerks did NOT use red ink - using black ink instead to indicate that postage was due. And they put the words “Short Paid” on the envelope. And, they included the number “126,” which was the amount (in cents) they expected to have sent back to them from the British Post Office.

Let me do the math on that one for you as well.

10 + 32 = 42

(10 cents for US internal mail + 32 cents for the US contract ship across the Atlantic)

42 x 3 = 126

(42 cents due to the British per 48 cent rate x a letter that weighed enough to require 3 such rates)

But that's not the big reason this envelope is interesting to me. The agreement between the US and the United Kingdom was written in such a way that if something was not fully prepaid, it was treated as if it was not paid at all. As a result, the recipient had to pay the full postage due (6 shillings) and the $1.20 in postage stamps essentially became a gift to the US Post Office.

This is why April 1, 1866 is a big day. The postal convention between the US and the UK had been effective since February of 1849. During that entire time, people who sent heavier letters could make a mistake and assume the postage rate was simply a multiple of 24-cents. As a result it was easy to accidently waste a significant amount of postage AND still leave the recipient to foot the bill.

I wonder how many strongly worded letters were sent both to the US Post Office and the British Post complaining about this very situation. There were probably a fair number of them, but it still took seventeen years before the situation was addressed.

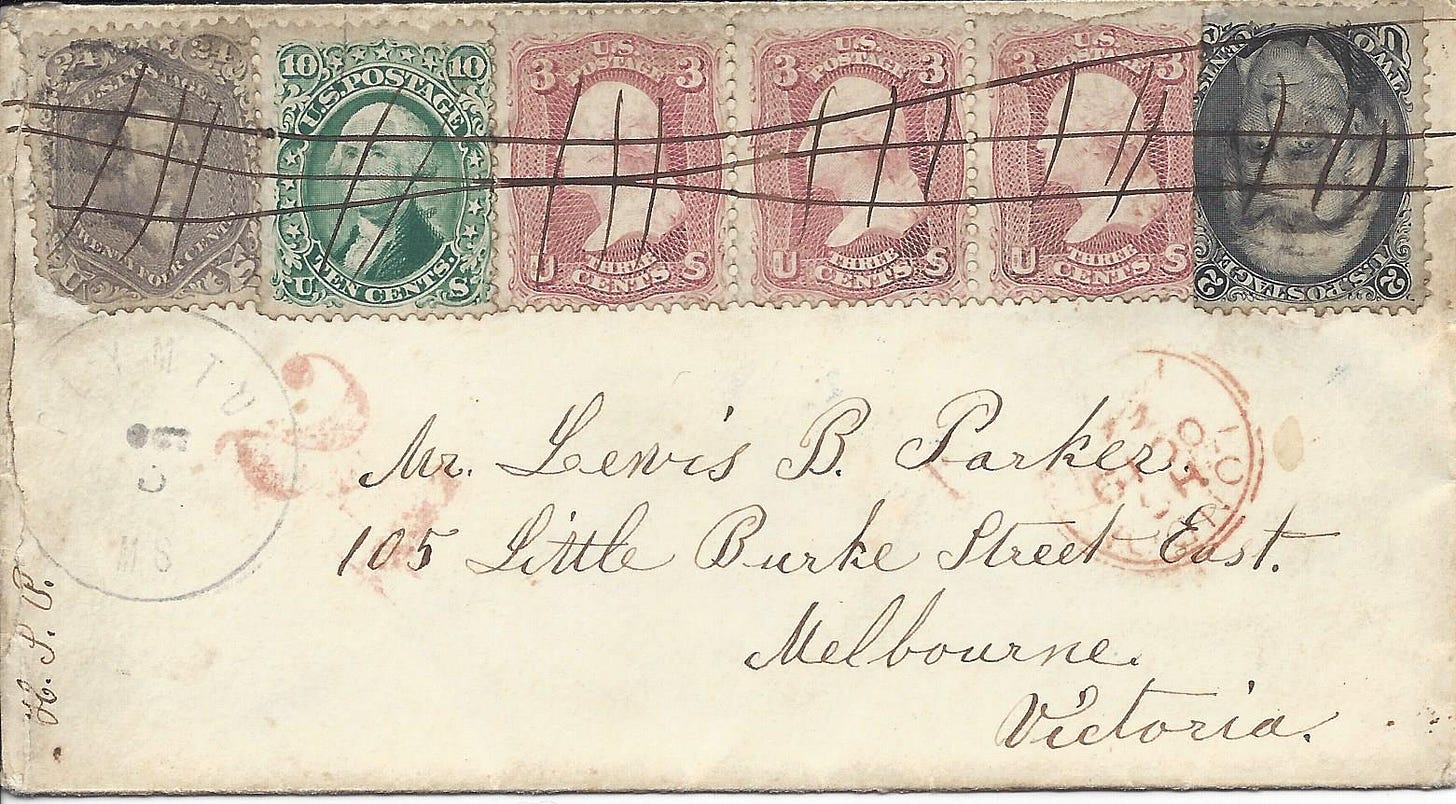

The 20th and 26th of the Month: A Day’s Delay = Weeks to Pay

The envelope shown above was mailed in Rushville, Indiana, on June 13 or 14 of 1866. It was processed in the New York Foreign Mail Office on June 16 and crossed the Atlantic to London on its way to Australia. At the time, there was no contracted mail services that would cross the Pacific from the United States to get to locations such as Japan or Australia (that service would start in 1867). So, this letter had to cross the Atlantic, go around the Iberian Peninsula, travel through the Mediterranean, through the Suez, and on via India to the Far East.

That meant a person sending a letter to Australia from the US was actually at the mercy of the British Post Office’s schedule for the Australian mails.*

The British had a contract with the Peninsular and Oriental shipping line to provide a monthly service from Galle (Ceylon - now Sri Lanka) to Sydney (Australia). Yes, you read that correctly. There was one scheduled ship that departed Galle each month. As a result, the London office held on to letters until it was time to send them to Galle to meet the monthly sailing to Australia.

The British made it known that the mails to Australia and New Zealand were to be made up in London on the 20th each month to be sent via the Southampton route and the 26th via the Marseilles route. The Marseilles route was quicker (and required more postage) so it would arrive at Galle the same time as the letters that were sent via the Southampton route six days earlier.

As a result, most mail to Australia went via the cheaper Southampton rate since benefit could only be gained via Marseilles for mails processed in London between the 20th and 26th of each month.

*note: There were other postal services that provided service to Australia, such as the French. But those services were used much less often by US mailers.

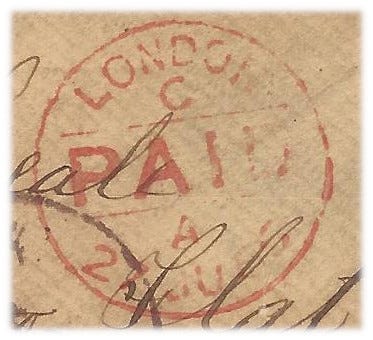

And now, I call your attention to this postmark on the cover in question. This is the London exchange marking that tells us when this letter was taken out of the mailbag sent from the United States. This letter was processed on June 27. One day after the mails left via Marseilles to get to Galle (and then Australia).

The reward for being one day late? This letter sat in London until July 20 (23 more days), when it was sent on its way. It would leave Galle on August 20 and it arrived in Kangaroo Flat in Victoria (Australia) on September 11.

It took about three months to get to the recipient. If it had arrived one day earlier, it could have gotten there in a little over two.

Now, before we get too excited. The sender of this letter paid for the Southampton rate (45 cents), which means they were probably quite aware that it would not get to London on time. But, it still clearly illustrates how a delay of one day cost weeks of future delays.

Our final cover for the day is another example of mail from the US to Australia. But, this time, the timing was about as good as it could be for the person who mailed the letter. Initially mailed at Plympton, Mass on October 5, it arrived in London and was taken out of the mailbag on October 19. The mail for Australia via Southampton was due to leave the next day!

This means the sender could pay for the cheaper postage rate (45 cents) and the letter would be sent on its way with minimal delay from London. If it had arrived one or maybe two days later, it would have required another 8 cents to take the fast route via Marseilles in order to catch the ship as it stopped at Malta.

In our world today, we have become used to electronic communications where someone in the US could send an email to a person in Australia now and they could (if they were awake and online at that moment) receive it in a matter of minutes. Imagine a world where there were no reliable “instant” communications methods and a delay of one day could make the difference between getting important information to someone in three months versus two months. It could easily have been a half year before a response was received!

Happily, you and I do not have to plan our communications quite so carefully. If you have questions, comments or corrections, I am always happy to receive them in comments on this article, via email, or other communications methods. If you want to send me a piece of real mail in the form of a letter, I’d even welcome that!

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

You commitment to bring one post out a week is just so admirable. As a writer, I know its harder than most things in the world! How do I email you to discuss a couple of points in this particular post?

Fun stuff, Rob!