The French Connection

Postal History Sunday #208

You blink, and you suddenly find that you are approaching the middle of August. It doesn’t matter if you gave the world permission to progress through the calendar or not. It just does it. It was only moments ago that we were celebrating PHS #200 but I am now seeing the number “208” appended to the title of this entry. And for those that like math: 52 x 4 = 208. There have been four years worth of Postal History Sunday with today’s entry.

Other than the introduction, I’m not going to take up too much time other than to point out that today’s topic was a leading vote-getter for the ideas offered in PHS #200. So we are celebrating by producing an article that had popular support from you - the good people who enjoy reading these writings.

Also, look for two mid-week offerings of older PHS articles that I think you’ll enjoy reading (or re-reading for a few of you). You can consider these gifts to help you get through the “dog days of Summer” if you like. Or they can be reminders that Summer is not over yet and you can allow yourself a few moments in time to pour yourself a cool drink and put your feet up while we we all learn something new.

For those of you who reside in the Southern Hemisphere, you can consider these as additional opportunities to relax with a warm drink while you surround yourself with a soft blanket. I’m sure it will work out either way.

When the Destination isn’t a Neighbor

Prior to 1875, nations operated under various agreements between countries for the exchange of mail. Of course, it made the most sense to set up postal conventions with neighboring nations. After all, there was bound to be more mail between bordering countries like France and Belgium than there might have been between countries such as Greece and Denmark.

Just use those examples and think about it for a second. How much mail do you think was passed between Greece and Denmark in 1855? If your answer is “probably not much,” you would be correct. So, I think you would understand if those two countries didn’t spend time trying to hammer out a treaty between the two of them to handle their mail.

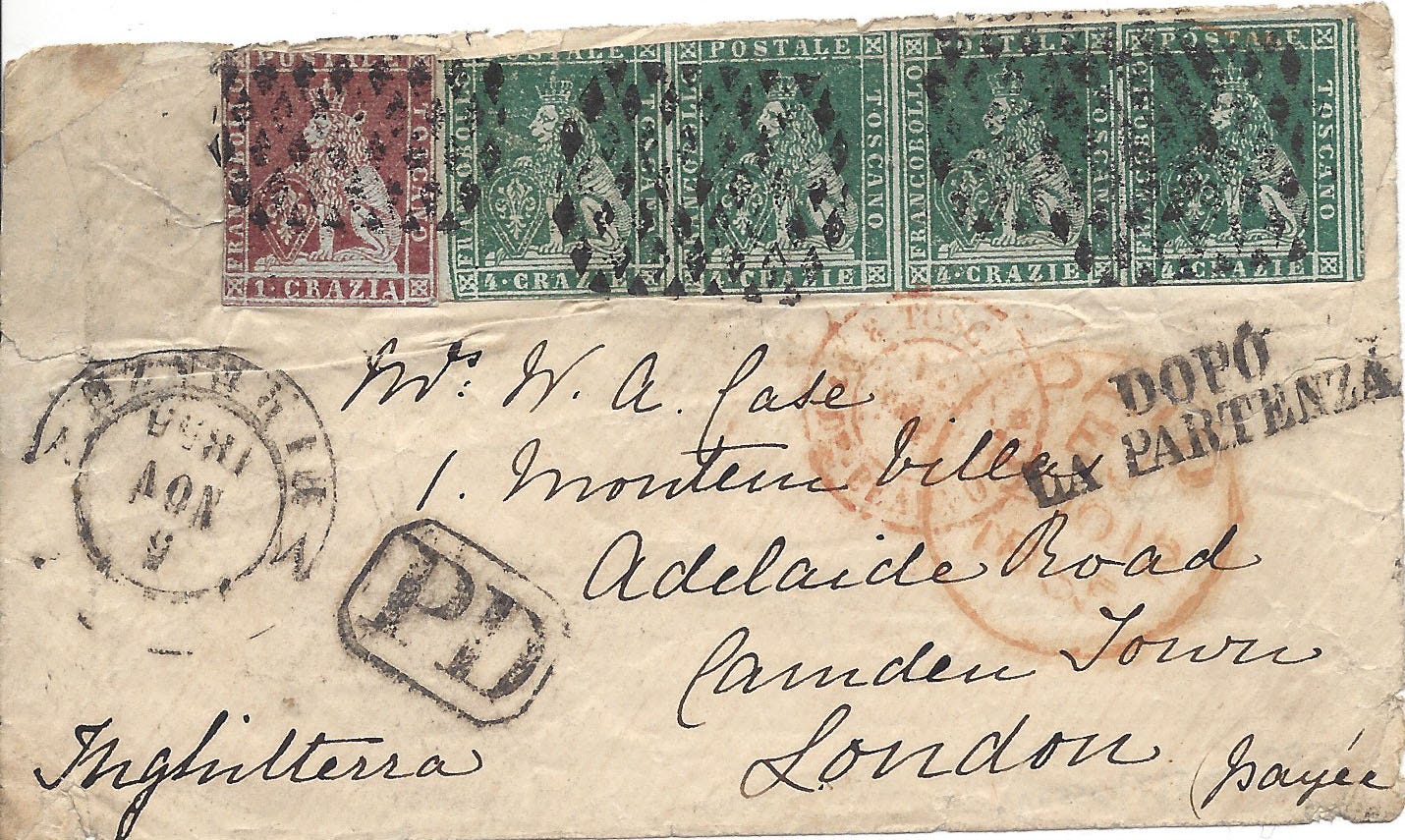

So, how was it possible for people to send a letter to a country that did not have a postal convention with their home country? The simple answer was that they relied on another country (or countries) to serve as an intermediary. The 1855 letter (shown above) sent from Firenze (Florence) in Tuscany to London illustrates the idea where France served as the connecting nation.

Tuscany signed a postal convention with France in 1851 that was in effect at the time this letter was mailed. And, France had just signed a new agreement with the UK that went into effect on January first of 1855. Both of those agreements provided a framework where the UK and Tuscany could send mail to countries that France had agreements with. Similarly, they could also receive mail from countries with whom France was able to exchange mail.

Now let me make this all a bit more confusing before we hopefully become less confused. Italy actually consisted of several independent states in the 1850s. While France had a postal agreement with Tuscany, they did NOT share a border. There was this little matter of Sardinia between the two. But, France also had an agreement with Sardinia (as of 1851) and Sardinia and Tuscany also had protocols for exchanging mail.

When all is said and done, getting mail from Tuscany to England required a chain of agreements that provided mechanisms to travel through at least two independent nations/states (Sardinia and France).

Because these agreements existed, a person in Tuscany could mail a letter to England for 17 crazie for each 6 denari in weight (effective Oct 1, 1851 - Dec 31, 1856). If you look at the stamps on this envelope, you will see four green stamps with the Tuscan Lion that are worth 4 crazie each and one reddish-brown stamp worth 1 crazia.

This letter was a simple letter (it weighed no more than 6 denari) so it was fully paid to get it to its destination in London. Fully paid meant that all costs for carrying this letter in Tuscany, Sardinia, France and England were accounted for in some fashion by the total postage. The methods for making sure each postal agency got the postage owed to them was outlined by the postal agreements.

Italy Had Many Flavors in the 1850s

If you click on the map above, you can see a larger version. The first thing you should notice is that Italy is broken up into several independent states (Sardinia, the Kingdoms of Lombardy and Venetia, Parma, Modena, Tuscany, the Papal States and the Two Sicilies). Each of these states had their own postal systems.

You know what that means?

That means each of them had to have agreements to exchange mail. Each time you involved another independent state, you introduced complexity and cost to how mail could get from one place to another.

If you are not familiar with the geography, Tuscany is in green, Sardinia is in red and France borders Sardinia to the West. If you look closely, you might also find that another Italian state would have to be crossed in order to get to Sardinia from Tuscany.

Yep, it looks like Modena gets into the fray too! But, I didn’t mention them on purpose. Why?

Well, it turns out that by the middle of 1852, several of these Italian States (Parma, Modena, Tuscany and the Papal States) had come to an agreement with Austria. This agreement essentially allowed each member state to exchange mail as if they were not foreign entities. So, mail from Tuscany could go through Modena without any extra cost added to the postage. But, Sardinia was not part of this group which means they would have to be a part of the chain of agreements to move mail on to France and England.

Now, let’s take a quick break to breathe - that was a lot to take in if you weren’t already familiar with it!

I am guessing that many of you are not familiar with all of the different monetary systems and the weight and distance measurements may be adding some frustration. So, let me put a few pieces of information here for you:

Money in Tuscany: 1 Tuscan lira = 12 crazie (crazia singular, crazie plural)

(or more accurately for the time, 1 Tuscan fiorino = 20 crazie = 100 quattrino)

Weight units in Tuscany: 1 denaro = 1.15 grams in weight. (denaro singular, denari plural)

Distance units in Tuscany: 1 Tuscan mile = 1.85 km

The postage rate actually decreased from 17 crazie to 12 crazie (effective Jan 1, 1857 - Jan 31, 1858) because the agreement between France and the UK decreased the agreed upon transit costs through the intermediaries. While savings of this sort weren’t always passed on immediately, changes in one agreement in the chain of agreements that followed a letter from the origin to destination could certainly alter how mail was carried and how much it cost.

Let’s Just Send One TO France

I know some of you who read Postal History Sunday like geography and maps. So, let’s take a look at a letter that went from the Papal States to France so we can look at the route this letter took to get from one place to another.

We get two clues in the form of postal markings on the front of this envelope. The first tells us the letter was mailed in Bologna on May 22, 1856. The second is a French exchange marking in red ink.

This marking reads “E. Pont” and “Pont De B.”

French exchange markings during this time period identified the origin country (E. Pont. or Etats Pontificaux or Papal State) and the exchange office where the French took over control of this mail item (Pont De B or Pont de Beauvoisin).

This envelope traveled through the Italian States of Modena and Parma. It went through a portion of the Kingdom of Lombardy and it crossed through Sardinia before entering France at Pont de Beauvoisin.

Once again, most of these Italian States were part of the Austro-Italian Postal League so this letter was not treated as if it had crossed a border. That means this letter stayed in its mailbag or mail packet as it traveled from Bologna to Reggio to Parma and Milano. None of those postal authorities had reason to process this letter at all.

Once the letter got to Sardinia, the Austro-Italian Postal League’s agreement no longer applied. What applied here was an agreement with the French that Sardinia would transmit mail to France in closed mailbags (or packets). This is often refered to as “closed mail” and it simply meant that Sardinian postal clerks would not handle individual mail items intended for France from the other Italian States. The mailbag would not be opened until it reached France, which is why we have a Pont de Beauvoisin exchange marking.*

* For those who like complete accuracy, this marking was actually applied in Paris to reflect the point when the letter entered the French mail. The reasons for that are for another day and another Postal History Sunday.

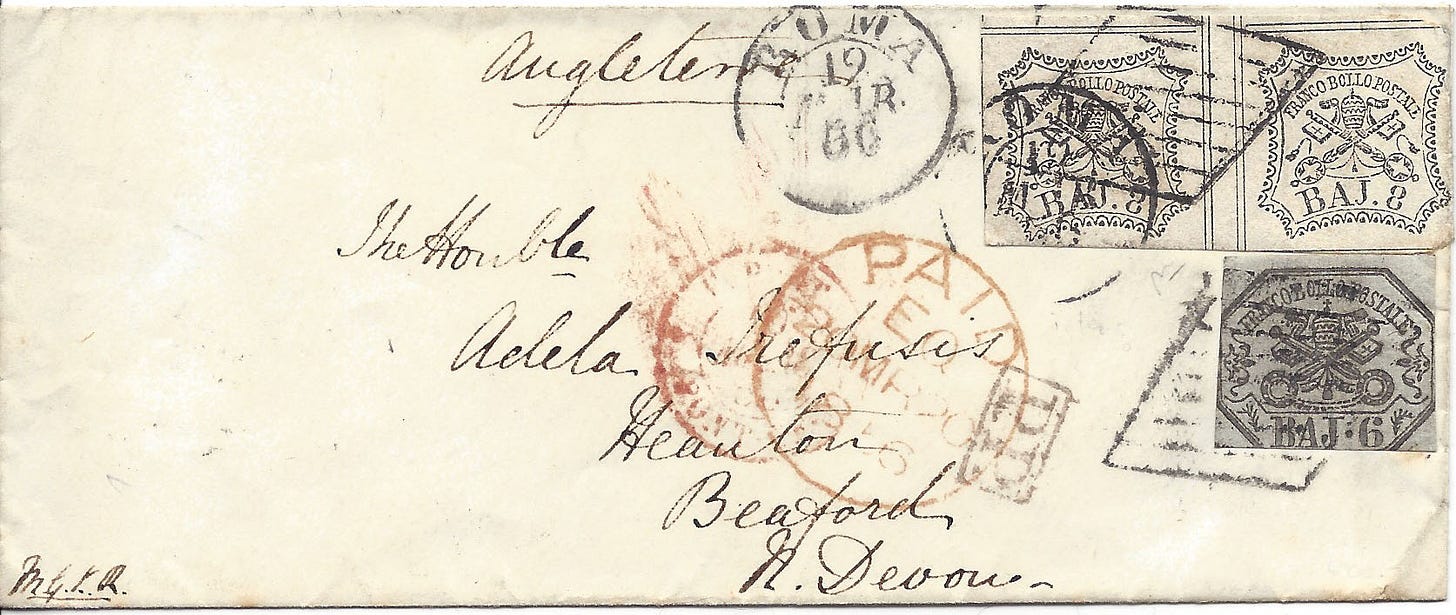

Since we started with examples from Tuscany to England and we were talking about France’s role as an intermediary for mail from the Italian States to England, let’s look at a letter that starts in Rome and goes to England!

The postal markings are

Roma (Rome)

French exchange marking in red (smaller) for Pont de Beauvoisin

British exchange marking in red (larger) for London

Typically, an exchange marking can be found each time a letter changes from one postal system to the next as long as the postal agreement calls for open mail. That’s why we see both a French and British exchange marking. Since Sardinia was a closed mail agreement with France, there will be no Sardinian marking. And, the other Italian States (Modena and Tuscany) were in the Austro-Italian Postal League, which means they didn’t consider mail between them as foreign mail.

The other thing to notice here is that the postage required to send a letter from the Papal States to England was 22 bajocchi (effective Apr 1, 1855 to Jun 17, 1866). The rate to France was 20 bajocchi. This provides you with evidence of the cumulative nature of the costs for postage as you add intermediary postal services.

If the letter was intended to go even further to some place like… oh… the United States - what would that mean for the postage costs?

The cost of this letter to the United States from Rome was 32 bajocchi. This additional cost reflected the crossing the Atlantic Ocean and the expectation that the US postal costs would also be paid for. Like the letters between the Italian States and the United Kingdom, the French connection was still in place.

Thank you for joining me today. Have a fine remainder of your day and an excellent week to come.

Postal History Sunday is featured weekly on this Substack publication. If you take this link, you can view every edition of Postal History Sunday, starting with the most recent publication. If you think you might enjoy my writing on other topics, I can also be found at the Genuine Faux Farm substack. And, some publications may also be found under my profile at Medium, if you have interest.

I didn't realize that Sardinia was more than just the island back in the day. So I managed to learn something today.

Ah! We have a 4 year old in the house. That explains so much!